Abstract

Stress in daily life is rather common, but elections can present unique challenges. Evaluating the impact of individual characteristics, behaviors, and political beliefs on stress processes is imperative to understanding how elections influence psychological well-being. Exploring how these individual and behavioral characteristics interacted to predict exposure to election-related stressors, we hypothesized that age, education, and past socio-political involvement would be associated with exposure to election-related stressors. In the 2018 U.S. Midterm Election Stress Coping and Prevention Every Day (ESCAPED) study, 140 participants in the United States and territories aged 19–86 were recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk for a 30-day daily diary study. Collectively, participants completed a total of 1196 reports between October 15, 2018 and November 13, 2018. The midterm election was November 6, 2018. Each day, participants reported on past political participation, election stress anticipation, and exposure to election-related stressors. Confirming our hypothesis, on days when people were more politically active and on days when stress anticipation increased, exposure to election-related stressors increased. Age differences in exposure depended on political activity in the last 24 h, with older adults exhibiting a steeper increase in exposure following political activity, especially if they were highly educated. However, higher education was protective against election-related stressors among younger adults even with increases in political activity. Individuals’ experiences, characteristics, and daily decisions influence the likelihood of exposure to election-related stressors. Additionally, for younger adults, education may function as a protective factor when they engage in political activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Political involvement of citizens is one of the pinnacles of any functioning democracy (Lanning, 2008). Participating in the political process can include activities such as protesting, assisting with a political campaign or issue, contacting representatives, and voting. Voting by citizens is critical to fuel strong democracies, yet voter participation is often disappointingly low (Desilver, 2018). Although people may face stressful situations or decision making tasks daily, political elections are noted as profoundly stressful events (Waismel-Manor et al., 2011). Adults who have a greater sense of political self-efficacy (which can include placing importance on politics in one’s life, voting, and exposing one’s self to election-related media) may feel increased psychological distress after an election, especially if their candidate loses (Pitcho-Prelorentzos et al., 2018). An increase in emotional reactivity may be particularly apparent in the days directly following an election (Neupert et al., 2021). Furthermore, those who report higher levels of perceived negative impact based on an election are more likely to report lower levels of physical and mental health (Koerten et al., 2019). Understanding the interconnectedness of democratic engagement and daily stressor exposure is imperative when considering elections in relation to well-being and how these stress processes may unfold within a person over time.

Political Participation

Much of the existing literature on political participation revolves around voting, but there are many other methods of participating in the political process. Thus, the present study incorporates a wide range of political activities including participating in a civil rights group, attending a political rally, engaging in political conversations, etc. Voting in an election involves the social aspect of attending a polling place as well as formulating a political decision; both of these actions can cause an elevation in cortisol levels for those who vote in person (Neiman et al., 2015). But, voting at a polling place is not the only method of casting a vote. While voting by mail in the U.S. has been met with considerable opposition, Southwell and Burchett (2000) reported a 10% increase in expected voter turnout in Oregon from 1995 to 1996 after all-mail elections were adopted due to unique circumstances, indicating that the option of voting by mail can make participation more accessible. It is important to acknowledge that voting is crucial, but not the only way to participate in politics. An individual’s subjective psychological well-being can be impacted by their participation in political activities (Lorenzini, 2015) such as advocating for a social cause, writing a letter to a public institution, and working on a political campaign.

Age Differences

Previous findings have illustrated clear differences between the political involvement of younger and older adults. Plutzer (2002) suggested that electoral behavior is habitual, as well as developmental, meaning that factors prone to change over a person’s life may shape their voting practices. Discrepancies in turnout could be explained by older voters typically having an increased stake in economic issues, including social security and home ownership, in addition to the fact that older adults tend to embrace value-based justifications for their preferences (Chrisp & Pearce, 2019). Young adults are generally labeled as apathetic or avoiding civic duties, but unconventional means of action, such as social media engagement and volunteering, have indicated that young voters may be motivated, but do not use traditional modes of participation as frequently as older adults (Shea, 2015). Many young adults feel anxiety or fear before and after an election due to a lack of control over circumstances, potentially resulting in poor physical health outcomes (DeJonckheere et al., 2018). Even though younger citizens vote at a lower rate than older adults, the outcomes of elections have lasting effects on all people within the country.

Exposure to Political Events and Media

Political cognition and exposure to different media outlets are often factors that contribute to people actively taking part in the democratic process. Media is able to frame political issues from a particular perspective, shaping public debate on any given subject (Happer & Philo, 2013). Today, more than half of American adults report that social media interactions with those who have differing political views are stressful and frustrating (Duggan & Smith, 2016). More than one third of American social media users report that they are “worn out” by the amount of political information that they are exposed to on their feeds (Duggan & Smith, 2016). Exposure to news media with political content is positively associated with political knowledge and participation as well as the likelihood of voting in an upcoming election (de Vreese & Boomgaarden, 2006). Media usage can influence attitudes and behaviors by confirming or contradicting individuals’ values, ultimately impacting which political activities people choose to participate in (Firat, 2014). Conversely, individuals may seek out media information related to political events to affirm their beliefs or mitigate their stress in response to the ever changing and nebulous political theater (Newman et al., 2018). Regardless of the motivation to access media regarding political events, it is undeniable that news media has a significant impact on how individuals in the United States experience elections.

The means through which younger and older adults inform themselves on political issues differ drastically. Younger adults are more likely to receive news from online sources while older adults are more likely than their younger counterparts to obtain news from print newspapers or the radio (Mitchell et al., 2016). Although age differences exist in exposure to political events, many adults remain involved in the political process through activities such as protesting, participating in political and civil rights organizations, contacting representatives, and working on a political campaign. Additionally, many young adults have turned to social media activism to bolster support around political and social issues (Shea, 2015). The Black Lives Matter movement is a contemporary example of how the utilization of social media has created an accessible platform to engage in conversations about systemic inequality and police brutality (Carney, 2016). According to the Pew Research Center, 41% of those who attended protests and rallies in 2020 that erupted across the U.S. were aged 18–29, even though this age group comprises 19% of the nation’s total population (Barroso & Minkin, 2020). Today, there are a variety of activities that qualify as political engagement and diverse ways to be engaged.

Level of Education

In the United States, more socially privileged citizens, as defined by years of education, vote at a higher rate than those who are less privileged, highlighting a trend of unequal voter turnout among different populations (Gallego, 2009). Research asserts that there is a positive relationship between a person’s political involvement and their formal education (Hillygus, 2005) and there is a positive relationship between educational attainment and whether one considers voting to be a civic duty (Hansen & Tyner, 2021). The level of education an individual earns appears to be the strongest indication of political knowledge and civic engagement (Hillygus, 2005). Education serves as a predictor of participation because students may become intrigued about the civic process and learn about the importance of registering to vote through their classes (Harder & Krosnick, 2008). Educational attainment further exemplifies differences between individuals that influence political involvement.

Political Orientation

Due to the prevalence of political issues in daily life, political orientation must be examined as one’s political ideologies impact them in a multitude of ways, including their well-being. Research has found that those who identify as politically conservative report greater subjective well-being compared to those who identify as liberal (Napier & Jost, 2008; Briki & Dagot, 2020). This could be because those who are conservative tend to rationalize their political views through system-based justifications which affirm that institutions in society are fair and should remain in place even if inequality is present, while those who are liberal do not readily adopt such justifications (Napier & Jost, 2008). Hence, individuals who identify as liberal are more negatively affected psychologically by social inequality (Napier & Jost, 2008). Individual differences, such as political orientation, contribute to one’s well-being, which could be particularly impacted around the time of an election.

Exposure and Response to Stressors

In addition to differences between people, there are also within-person processes that unfold over time which are important to consider. In particular, exposure and responses to stressors are highly contextualized and can change day-to-day (Almeida, 2005; Neupert & Bellingtier, 2019). While stressors occur on a daily basis, some are unavoidable. Due to the cyclical nature of the U.S. political process, elections are inevitable and the consequences of elections are uncertain. Waiting for pending results of events with unknown outcomes can affect people both physically and psychologically (Sweeny, 2018). Stress anticipation involves the expected level of stress associated with a given upcoming event (Neupert et al., 2019; Powell & Schlotz, 2012), and previous work has shown that there are age differences in stress anticipation across a variety of domains (e.g., home-related stressors; Neupert & Bellingtier, 2019). However, no work to date has examined the role that stress anticipation within the context of an election may play in subsequent stressor exposure. The age of an individual may also have a considerable impact on how that person will forecast and respond to future stressors.

Theoretical Framework

The notion that there are age differences in anticipation, exposure, response, and avoidance of stressors is supported by previous literature and emphasised in the theoretical framework of the Strength and Vulnerability Integration Model (SAVI; Charles, 2010). SAVI suggests that older adults have the benefit of utilizing life experiences to assist them in avoiding future stressors, but they experience increased psychological inflexibility in response to stressor exposure as compared to younger adults (Charles, 2010). According to SAVI, older adults could be motivated to avoid election-related stressors due to the psychological damage they may cause, while younger adults may have less difficulties when confronted with these stressors. In order to mitigate potential psychological repercussions that could occur following stressor exposure, it is important to consider age-related vulnerabilities and adaptations that exist, as well as individuals’ behaviors and choices, in the processes that precede election-related stressor exposure. This study aims to build upon the theoretical framework proposed by Charles (2010) with respect to age differences and stressor exposure and extend it to the context of election-related stressor exposure that unfolds on a daily basis.

The Present Study

Not all people are affected by elections in the same manner. Differences between individuals relate to their level of stress and that stress could influence their political behaviors in the future (Hassell & Settle, 2017). There remains a lack of knowledge as to how age, level of education, and past socio-political participation simultaneously contribute to an individuals’ exposure to political events and the stress that they report during the time of an election. This study is innovative and distinct from previous literature in that the data were collected through online daily diary questionnaires to evaluate relationships and changes that exist within individuals over time. The microlongitudinal nature of daily diary methodology allows us to examine election stressor processes as they unfold over time, rather than a single snapshot that is taken with typical cross-sectional studies. To our knowledge, no research has investigated these processes at the daily level making this study both theoretically and methodologically unique within the current context. Evaluating the impact that these factors have on stress processes is crucial and necessary to understanding how elections influence well-being and to what extent adults expect to feel stress related to an impending election. Research on these processes is imperative because of the continuous and cyclical nature of elections and the prevalence these stressors have in the lives’ of those who live in the U.S.

In this study, we explore the relationship that age, level of education, past socio-political participation, political orientation, and daily anticipated levels of stress have on daily exposure to election-related stressors before, during, and after an election. We hypothesize that age, education, and past socio-political involvement would be associated with exposure to election-related stressors. Additionally, we hypothesize that increases in anticipating election-related stress would correspond to a greater likelihood of exposure to election-related stressors.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

In order to understand the relationship between age, level of education, past political involvement, political orientation, exposure to election-related stressors, and anticipation of election-related stress, participants took part in the 2018 U.S. Midterm Election Stress Coping and Prevention Every Day (ESCAPED) study (Zhu & Neupert, 2021). After the participants were recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (mTurk), they were presented with a survey link to click on that redirected them to Qualtrics. The screen first displayed the informed consent approved by the institution’s IRB. Those who consented and indicated that they were not employees of North Carolina State University were directed to the survey questions for that day. Those who did not consent or indicated that they were an employee of North Carolina State University were unable to continue with the survey. Participants were compensated $1.00 for each day that they completed the designated questionnaire for that day.

Participants completed daily surveys online through Qualtrics survey software everyday from October 15, 2018 to November 13, 2018. The baseline survey administered on the first day of the study, October 15, 2018, inquired about the participants’ age, level of education, and political orientation and other information not analyzed in the current study such as personality. For the subsequent 29 days of the study, daily measures of past socio-political participation, stress anticipation, and election-related stressor exposure were completed through the daily dairy questionnaires on Qualtrics. A unique survey was launched each day for 30 days; a maximum of 30 separate surveys could be collected consecutively for each participant. Each survey was available for participants to complete for a 24 h period. Only participants who completed the Day 1 survey were able to participate in the following 29 days of the study. These surveys were given prior to, during, and after the U.S. midterm election of 2018 on November 6, 2018.

A total of 140 participants were recruited from mTurk, producing 140 baseline and 1056 daily surveys. The participants for the study overall ranged in age from 19 to 86 years (M = 33.75, SD = 7.33). All of the participants reported residing in the United States and territories (i.e., American Samoa). From the data collected, 53% were men, 47% were women, 74% were white, and 12% were African American.

Baseline Measures

Age was measured by asking participants to indicate their date of birth as well as their numerical age. These were then matched to ensure data quality.

Education was measured by asking participants the highest level of education that they completed by selecting from a list of 12 items ranging from 1 (no school/some grade school) to 12 (Ph.D., MD, or other professional degrees).

Political Orientation was measured using a single item asking participants to rate their political orientation from 1 (liberal) to 6 (conservative).

Daily Measures

Daily Election Stress Exposure (Frost & Fingerhut, 2016) was measured by asking participants if they had exposure to specific items within the last 24 h in regard to the midterm election. Participants responded by selecting “yes” or “no” to political exposure items including “saw television report(s) about the midterm election,” “listened to radio program(s) about the midterm election,” or “saw posting(s) on a social networking site (e.g., Facebook) about the midterm election.” Exposure is represented by the sum of “yes” responses.

Anticipation of Election-Related Stress was measured by asking participants, “How likely is that you will experience stress related to the midterm election within the next 24 hours?” on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all likely) to 5 (extremely likely).

Past Socio-Political Participation was measured using the Critical Consciousness Scale (Diemer et al., 2015) adapted for daily use. Participants were presented with a list of 10 political participation items and selected either “yes” or “no” based on whether they had participated in certain activities within the last 24 h. Items included whether a person had “participated in a civil rights group or organization,” “contacted a public official by phone, mail, or email to tell him or her how you felt about a social or political issue,” “joined in a protest, march, political demonstration, or political meeting,” or “posted a message or image on social media about a social or political issue.”

Analyses

Prior to conducting any inferential statistics, all study variables were evaluated for normality and potential influence of extreme scores. Aside from an expected positive skew with respect to age (skew = 1.55), all other variables appeared to be symmetrical and normally distributed. In particular, the outcome variable of election-related stressor exposure (skew = -0.08) met assumptions for normality and linearity.

We analyzed the daily diary data using multilevel modeling (MLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) because the data were nested (days nested within people) and we were interested in intraindividual (within-person) variability, that is, people’s fluctuations around their own mean. MLM was implemented using SAS Institute (2013) Proc Mixed with the REML estimation method. This method allowed us to analyze all available data from each participant, regardless of the number of daily surveys they completed.

We investigated individual differences in age, education, and political orientation and daily fluctuations in socio-political participation and anticipated stress on exposure to election-related stressors through the equations below. The intercept (β0) and slopes (β1 - β2) from Level 1 become the outcome variables at Level 2. The unexplained variance at the within- and between-person levels is modeled by rit and u0i, respectively:

Level 1 (daily): Exposureit = β0it + β1it(anticipated stress) + β2it(socio-political participation) + rit

Level 2 (person): β0i = γ00 + γ01(political orientation) + γ02(age) + γ03(education) + γ04(age*education) + u0i

β1i = γ10

β2i = γ20 + γ21(age) + γ22(education) + γ23(age*education)

These equations represent the within-person (Level 1) and between-person (Level 2) effects. β1 represents the within-person relationship between anticipated stress and exposure, and β2 represents the within-person relationship between socio-political participation and exposure. The sample average of these effects are operationalized as γ10 and γ20, respectively. Individual differences in exposure based on political orientation (γ01), age (γ02), education (γ03), and the interaction of Age x Education (γ04) are modeled in the equation for the intercept (β0i). Our main research questions are addressed by the predictors of the within-person slope of socio-political participation and exposure. Specifically, age (γ21), education (γ22), and the interaction of Age x Education (γ23) in the equation for the target slope (β2) represent our cross-level interactions of interest.

Results

Descriptive statistics and between-person correlations for the variables in the study can be found in Table 1. Age was uncorrelated with all study variables, but people with higher levels of education and those with more conservative political orientation reported more socio-political participation. Furthermore, Table 1 demonstrates that exposure to election-related stressors and anticipation of election-related stress were positively correlated with education and past-political participation. Moreover, anticipation of election-related stress was positively associated with daily exposure to election-related stressors. Results from a fully unconditional model (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) suggested that 74% (τ00 = 8.73, SE = 1.17, p < .0001) of the variability in election-related stressor exposure was between people and 26% (σ2 = 3.02, SE = 0.13, p < .0001) of the variability in election-related stressor exposure was within people.

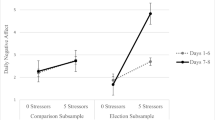

Results from the multilevel model are in Table 2. There were no main effects of political orientation (γ01) or age (γ02). Those with more education reported more election-related stressor exposure (γ03), and there was an interaction between age and education on the level of exposure (γ04). Daily increases in anticipation of feelings of stress (γ10) as well as increases in political activity (γ20) were each associated with increases in election-related stressor exposure. There were age (γ21) and education (γ22) differences in the within-person relationship between political activity and exposure, which were qualified by the significant 3-way cross-level interaction of Age x Education x Political Activity (γ23, see Fig. 1). For older adults with higher levels of education, increases in past political activity were more strongly associated with their election-related exposure than younger adults with higher levels of education (right side of Fig. 1). Our findings additionally indicate that increases in political activity were linked to increases in stressor exposure for those with lower levels of education, regardless of their age (left side of Fig. 1). This model explained 56% of the between-person and 10% of the within-person variance in daily election-related exposure.

Significant 3-way interaction of Daily Past Socio-Political Activity x Age x Education predicting daily election related stressor exposure. Increases in political activity were linked to increases in stressor exposure for those with lower levels of education, regardless of their age (left side). For older adults with higher levels of education, increases in past political activity were more strongly associated with their election-related exposure than younger adults with higher levels of education (right side).

Discussion

The present study examined individual differences in age, level of education, and political orientation along with daily changes in socio-political involvement and anticipation of election-related stress to understand changes in daily exposure to election-related stressors within the context of the 2018 U.S. midterm election. While previous research suggested that political elections can be particularly stressful events in one’s life (Waismel-Manor et al., 2011), the relationships between the variables in this study had yet to be concurrently investigated. Acknowledging how these factors interact with one another is vital to understanding the factors underlying participation in the political process and stressor exposure related to an election. Although our results are correlational, this work illustrates the dynamic nature of these constructs as they unfold over time, subsequently laying the groundwork for future investigations into the (likely) bidirectional nature of these relationships across time. Our results show that individual differences (e.g., age, education) interact with situational changes (e.g., daily socio-political participation) to predict changes in daily election-related stressor exposure.

Exposure to election-related stressors such as watching a television commercial related to the election, viewing social media posts about the election, or participating in a conversation about the election was associated with being more likely to anticipate feeling stress related to the midterm election in the next 24 h. Previous work has shown that there are age differences in stress anticipation across a variety of domains (e.g., home-related stressors; Neupert & Bellingtier, 2019), but our results suggest that daily increases in stress anticipation related to an election are consistent across age with respect to increases in election-related stressor exposure.

Although there were no age differences in election-related stressor exposure, older adults may experience worse psychological consequences when they are faced with unavoidable stressors, in line with SAVI (Charles, 2010). According to the SAVI model, older and younger adults react differently to stressors depending on their stage in life (Charles, 2010). The model posits that older adults are more likely to employ life experiences and learned skills that they can leverage to adaptively approach daily stressors as compared to their younger counterparts, especially with respect to stressor avoidance (Charles, 2010). Older adults have vulnerabilities in their reactions to stressors, such as psychological inflexibility, that could lead to greater difficulties responding to sustained stressors, particularly when they are confronted with stressors that they are unable to avoid (Charles, 2010). Elections are unique stressors in that their outcomes are unknown, but their timing is predictable and fixed.

Election-related stressors may be particularly challenging for older adults to avoid, but eligible adults should be encouraged to participate in the political process because public policy can affect all people within the country. Effectively informing citizens about how they can utilize convenience voting in their state may influence how citizens will cast their vote (Herrnson et al., 2019), which could also impact the stress that one feels in relation to an election. The Pew Research Center (2020) found that older adults are more likely than younger adults to utilize mail-in voting. Mail-in voting could be a strategy that could be particularly beneficial for older adults in order to reduce their exposure to election-related stressors. Adults can employ strategies to mitigate negative outcomes that they may experience after stressor exposure including limiting future social media usage or making a political participation plan of action for themselves.

Adults with higher levels of education reported more exposure to election-related stressors on average than adults with lower levels of education. Elections may be particularly stressful for those with a stronger sense of political-self efficacy (Pitcho-Prelorentzos et al., 2018). This could help explain the relationship between education and election-related exposure. Those who have received higher levels of education may place more significance on politics in their daily lives and may better understand how policies could affect them personally. Exposure to election-related stressors may begin early in one’s life. For example, the habitual behavior of voting can potentially be established within a classroom environment. Schools may teach students about registering to vote and capturing their interest in the civic process (Harder & Krosnick, 2008). The level of education an adult receives is particularly influential in determining their political knowledge (Hillygus, 2005) as well as their likelihood of exposure to election-related stressors.

Beyond the main effect of education, our 3-way interaction emphasized the differential impact of education by age and daily political activity. Education may serve a valuable role in minimizing psychological impacts of socio-political participation, specifically when considering younger adults with high levels of education. There is a well known positive relationship between higher levels of education and political involvement (Gallego, 2009; Hillygus, 2005). Our findings indicate that education interacts with daily political activity, as those with lower levels of education experience stronger increases in election-related stressor exposure with increases in socio-political activity, compared to those with more education (see left side of Fig. 1). In contrast, young, highly educated individuals experience the weakest increase in election-related stressor exposure when they engage in political activity (see right side of Fig. 1). Younger adults with high levels of education may be better equipped to weather the effects of political participation for several reasons. Firstly, their youth and education may provide psychological flexibility as resources to manage stressors, in line with SAVI (Charles, 2010). Secondly, they are also more likely to have been raised in an environment where their parents had high levels of education (Bömmel & Heineck, 2020). Whether intentionally or unintentionally, these parents with high levels of education often expose their children to political issues and events (Bömmel, & Heineck, 2020), inferring that the children are socialized to inquire about issues and participation themselves. Lastly, on an individual level, people are more likely to surround themselves with peers that share similar norms and values (McPherson et al., 2001). Thus, educated younger adults are motivated to create personal connections with other adults that partake in similar activities (which applies to political activities). This notion also includes younger adults gravitating towards social media accounts that align with their opinions. Individual and contextual factors in culmination explain why education may act as a buffer for psychological consequences of political participation through socialization.

Previous research found that those who identify as politically conservative generally report greater subjective well-being compared to those who identify as liberal (Napier & Jost, 2008; Briki & Dagot, 2020). However, our research indicates that political orientation was not a significant predictor of election-related stressor exposure. Although people may expect election-related stress for various reasons, the level of stress is consistent for liberals and conservatives, suggesting that this is a widely applicable phenomenon. Adults could feel stress around the time of an election regardless of their political orientation because different social, economic, and environmental interests are at stake based on who is elected and who is not. Voters have policies and goals they wish to be enacted by their representatives. The outcomes of elections are unknown. The experience of waiting for the results of an event with uncertain consequences may have an impact on an individual’s health and well-being (Sweeny, 2018), but our results suggest that these stress-related processes during an election apply regardless of political orientation.

Factors within a person’s life may impact whether they will participate in such activities and their exposure to election-related stressors. Zhu and Neupert (2021) discovered that the 2018 midterm election resulted in disruptions to peoples’ core beliefs, indicating that elections have a substantial impact on subjective well-being. Political involvement in the United States has changed dramatically in recent decades, now including social media activism (Shea, 2015) and being a socially conscious consumer (Ward & de Vreese, 2011). Although many social media users on a variety of platforms report feeling frustrated after viewing political posts online, members simultaneously appreciate that these platforms are beneficial tools for political discussion, debate, and action (Duggan & Smith, 2016). Voters may be inclined to engage online to relieve feelings of election-related stress and anxiety, gain a deeper understanding on issues, or acquire some sense of control over the outcome of an election. Social media has become a meaningful mechanism in shaping people’s opinions based on the content they are exposed to and read regularly (Duggan & Smith, 2016). Recognizing how and how often people are exposed to election-related stressors is critical in order to understand whether an individual may be psychologically impacted following their exposure to a stressor.

Limitations and Future Directions

The results of this study should be considered in light of some limitations. The data utilized in this study established correlational relationships, therefore causal claims cannot be made. The majority of the sample identified as white. Future work should examine how racial and ethnic backgrounds may contribute to whether one is encouraged or discouraged from being politically engaged and how such demographic information may influence the stress that adults report before, during, and after an election. The sample size was rather small and the participants ranged greatly in age, which prevented us from stratifying by age. Future research should aim to recruit more participants who are stratified by age, to determine whether the current results may actually underestimate age-related differences. A mixed methods design, which could include questionnaires paired with interviews and reports, would also be a helpful method of collecting data in future studies related to well-being and elections. Further research conducted on the means through which adults are exposed to election-related stressors would provide more detail on how adults inform themselves on political issues. Utilizing lagged models where stressor exposure on one day predicts election-related information the next day may be beneficial in future studies. Voters might seek a variety of methods of relieving their election-related anxiety and this is a subject of note for future studies.

Since this study focuses on the midterm election in the U.S., the results may not generalize to elections in other democratic nations. Research surrounding future elections should consider the implications of contemporary issues, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and The Black Lives Matter movement. For example, COVID-19 could result in an increase in the number of people who vote by mail or vote early and decrease the number of people who vote in person on election day. This could influence future trends in voting methods as well as voter turnout and alter the way in which we currently conceptualize these processes. Social movements could increase the number of people who are politically involved. Participation of citizens is essential to the democratic process but other external factors impact who participates. Voter suppression tactics, such as voter identification laws, affect accessibility to political participation and are disproportionately harmful to minority and marginalized groups, thus impacting engagement in the electoral process (Hajnalet al., 2017). Future research should focus on how voter identification laws can act as a stressor for individuals and assess subsequent social and psychological outcomes. Finally, future research could evaluate how stress levels of adults may differ based on whether they reside in a battleground state or a state that historically votes for a certain party. This could impact the exposure that adults have to election-related stressors, thus possibly impacting their well-being.

Conclusions

This study examined the relationship that age, education, political orientation, past socio-political involvement, and stress anticipation have on election-related stressor exposure. In line with our hypothesis, those with higher levels of education reported more election-related stressor exposure than those with lower levels of education. On days when people were more politically active, exposure to election-related stressors increased. In addition, on days when participants experienced an increase in stress anticipation, they also experienced increased election related-stressor exposure. These relationships were independent of political orientation. Importantly, higher education was protective against election-related stressors among younger adults even with increases in political activity. Individuals’ experiences, characteristics, and daily decisions influence the likelihood of exposure to election-related stressors. Additionally, for younger adults, education may function as a protective factor when they engage in political activities. Understanding the factors that could lead a person to be exposed to election-related stressors and the election-related stress they feel provides novel insight into what contributes to an individual’s socio-political participation in the democratic process.

Availability of Data and Material

Study materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Informed consent did not allow for the sharing of data.

Code Availability

Analytic code is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Almeida, D. M. (2005). Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(2), 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00336.x

Barroso, A., & Minkin, R. (2020, June 24). Recent protest attendees are more racially and ethnically diverse, younger than Americans overall. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/24/recent-protest-attendees-are-more-racially-and-ethnically-diverse-younger-than-americans-overall/

Briki, W., & Dagot, L. (2020). Conservatives are happier than liberals: The mediating role of perceived goal progress and flow experience - A pilot study. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00652-0

Bömmel, N., & Heineck, G. (2020). Revisiting the causal effect of education on political participation and interest. IZA Institute of Labor Economics, 1–25

Carney, N. (2016). All Lives Matter, but so does race: Black Lives Matter and the evolving role of social media. Humanity & Society, 40(2), 180–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597616643868

Charles, S. T. (2010). Strength and vulnerability integration: A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 136(6), 1068–1091. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021232

Chrisp, J., & Pearce, N. (2019). Grey Power: Towards a political economy of older voters in the UK. The Political Quarterly, 90(4), 743–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12737

DeJonckheere, M., Fisher, A., & Chang, T. (2018). How has the presidential election affected young Americans? Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 12(8), https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-018-0214-7

Diemer, M. A., McWhirter, E. H., Ozer, E. J., & Rapa, L. J. (2015). Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of critical consciousness. The Urban Review, 47, 809–823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-015-0336-7

Desilver, D. (2018, November 3). U.S. Trails most countries in voter turnout. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/05/21/u-s-voter-turnout-trails-most-developed-countries/

de Vreese, C. H., & Boomgaarden, H. (2006). News, political knowledge and participation: The differential effects of news media exposure on political knowledge and Participation. Acta Politica, 41(4), 317–341. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500164

Duggan, M., & Smith, A. (2016, October 25). The political environment on social media. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2016/10/25/the-political-environment-on-social-media/

Firat, R. B. (2014). Media usage and civic life: The role of values. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 2(1), 117–142. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v2i1.113

Frost, D. M., & Fingerhut, A. W. (2016). Daily exposure to negative campaign messages decreases same-sex couples’ psychological and relational well-being. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19(4), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216642028

Gallego, A. (2009). Understanding unequal turnout: Education and voting in comparative perspective. Electoral Studies, 29(2), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2009.11.002

Hajnal, Z., Lajevardi, N., & Nielson, L. (2017). Voter identification laws and the suppression of minority votes. The Journal of Politics, 79(2), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1086/688343

Hansen, E. R., & Tyner, A. (2021). Educational Attainment and Social Norms of Voting. Political Behavior, 43, 711–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09571-8

Happer, C., & Philo, G. (2013). The role of the media in the construction of public belief and social change. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 1(1), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v1i1.96

Harder, J., & Krosnick, J. A. (2008). Why do people vote? A psychological analysis of the causes of voter turnout. Journal of Social Issues, 64(3), 525–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00576.x

Hassell, J. G., & Settle, J. E. (2017). The differential effects of stress on voter turnout. Political Psychology, 38(3), 533–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12344

Herrnson, P. S., Hanmer, M. J., & Koh, H. (2019). Mobilization around new convenience voting methods: A field experiment to encourage voting by mail with a downloadable ballot and early voting. Political Behavior, 41, 871–895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9474-4

Hillygus, D. S. (2005). The missing link: Exploring the relationship between higher education and political engagement. Political Behavior, 27(1), 25–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-005-3075-8

Koerten, H. R., Bogusch, L. M., Varga, A. V., & O’Brien, W. H. (2019). The perceived impact of the 2016 election: A mediation model predicting health outcomes. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 7(1), 651–664. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v7i1.1065

Lanning, K. (2008). Democracy, voting, and disenfranchisement in the United States: A social psychological perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 64(3), 431–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00571.x

Lorenzini, J. (2015). Subjective well-being and political participation: A comparison of unemployed and employed youth. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(2), 381–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9514-7

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a Feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415–444. https://doi.org/10.3410/f.725356294.793504070

Mitchell, A., Gottfried, J., Barthel, M., & Shearer, E. (2016, July 7). The modern news consumer. Pew Research Center. https://www.journalism.org/2016/07/07/the-modern-news-consumer/

Napier, J. L., & Jost, J. T. (2008). Why are conservatives happier than liberals? Psychological Science, 19(6), 565–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02124.x

Neiman, J., Giuseffi, K., Smith, K., French, J., Waismel-Manor, I., & Hibbing, J. (2015). Voting at home is associated with lower cortisol than voting at the polls. PLoS One, 10(9), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135289

Neupert, S. D., & Bellingtier, J. A. (2019). Daily stressor forecasts and anticipatory coping: Age differences in dynamic, domain specific processes. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby043

Neupert, S. D., Bellingtier, J. A., & Smith, E. L. (2021). Emotional reactivity changes to daily stressors surrounding the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Current Psychology, 40, 2832–2842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00215-y

Neupert, S. D., Neubauer, A. B., Scott, S. B., Hyun, J., & Sliwinski, M. J. (2019). Back to the future: Examining age differences in processes before stressor exposure. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby074

Newman, T. P., Nisbet, E. C., & Nisbet, M. C. (2018). Climate change, cultural cognition, and media effects: Worldviews drive news selectivity, biased processing, and polarized attitudes. Public Understanding of Science, 27(8), 985–1002

Pew Research Center. Sharp divisions on vote counts, as Biden gets high marks for his post-election conduct (2020, November 20). https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/11/20/sharp-divisions-on-vote-counts-as-biden-gets-high-marks-for-his-post-election-conduct/

Pitcho-Prelorentzos, S., Kaniasty, K., Hamama-Raz, Y., Goodwin, R., Ring, L., Ben-Ezra, M., & Mahat-Shamir, M. (2018). Factors associated with post-election psychological distress: The case of the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Psychiatry Research, 266, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.05.008

Plutzer, E. (2002). Becoming a habitual voter: Inertia, resources, and growth in young adulthood. American Political Science Review, 96(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055402004227

Powell, D. J., & Schlotz, W. (2012). Daily life stress and the cortisol awakening response: Testing the anticipation hypothesis. PLoS One, 7(12), e52067. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052067

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications

SAS Institute Inc. (2013). SAS/ACCESS® 9.4 Interface to ADABAS: Reference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc

Shea, D. M. (2015). Young voters, declining trust and the limits of “service politics”. The Forum, 13(3), 459–479. https://doi.org/10.1515/for-2015-0036

Southwell, P. L., & Burchett, J. I. (2000). The effect of all-mail elections on voter turnout. American Politics Quarterly, 28(1), 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X00028001004

Sweeny, K. (2018). On the experience of awaiting uncertain news. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(4), 281–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417754197

Waismel-Manor, I., Ifergane, G., & Cohen, H. (2011). When endocrinology and democracy collide: Emotions, cortisol and voting at national elections. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 21(11), 789–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.03.003

Ward, J., & de Vreese, C. (2011). Political consumerism, young citizens and the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 33(3), 399–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443710394900

Zhu, X., & Neupert, S. D. (2021). Core beliefs disruption in the context of an election: Implications for subjective well-being. Psychological Reports. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941211021347

Funding

The funding was provided by a Faculty Research and Professional Development grant from the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at North Carolina State University to Shevaun D. Neupert.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

The North Carolina State University IRB approved the protocol of the present study on August 23, 2018. In order to conduct this study, the treatment of human participants was in accordance with APA Ethical Principles.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Early, A.S., Smith, E.L. & Neupert, S.D. Age, education, and political involvement differences in daily election-related stress. Curr Psychol 42, 21341–21350 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02979-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02979-2