Abstract

The effects of Covid-19 have been felt worldwide and one population that are of increasing concern are university students. University students have endured unique and drastic changes to their everyday and academic lives. It is important to understand how university students in different parts of the world have been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic and how it has affected their mental health? A cross-sectional study was conducted during the first wave of Covid-19, in May 2020 with 2,006 university students from the UK, Italy, Germany and Spain. Participants were recruited online and were asked to complete a series of standardised measures of psychological distress, anxiety, flourishing and wellbeing. Attitudes towards Covid-19 were measured using a new scale. The factor structure and reliability of this new scale was confirmed using this European sample. Results indicated that all university students were suffering from poor mental health, considerably below pre-pandemic norms. There were many geographical differences in the way that university students perceived the Covid19 pandemic, in terms of their fears, anxieties, loneliness and positivity. There were also significant mental health comparisons between students from the UK, Italy, Germany and Spain. Student beliefs that their government had provided effective leadership during the Covid-19 pandemic were strongly related to numerous mental health outcomes. A picture of university students’ mental health is provided and discussed. Geographical comparisons are discussed, as are the implications for practice and future directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Germany and Italy were among the first European countries to report confirmed Covid-19 cases at the end of January and beginning of February 2020. It was not until March 2020 that the World Health Organisation declared Covid-19 to be a pandemic and by July 2020 there were 3.31 million Covid-19 cases in Europe (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control 2021). Different governments around Europe are taking a wide range of measures in response to the Covid-19 outbreak and are divergent in the timing, duration and extent of their responses. The Covid-19 pandemic is being experienced differently by each country and the way in which each countries government handles the pandemic will have a huge influence on the perception and experience of the pandemic by individuals of society. The Covid-19 pandemic is affecting all of Europe and while the incidence of cases are broadly growing, the number of cases and subsequent hospitalisations and deaths are varying. Four countries which have been affected by the Covid-19 outbreak, particularly early on in the pandemic, are Italy, Spain, Germany and the United Kingdom. Each of these countries have had a unique experience and governmental reaction to the pandemic.

Italy

The first case of Covid-19 in Italy was confirmed on the 31st January, when two Chinese tourists tested positive in Rome. It was around three weeks later, on the 23rd of February, that the Italian government announced twelve ‘red zones’ and set out strict containment measures for the most affected territories (Sanfelici, 2020). It was not until the 8th of March that schools and universities were closed. When the World Health Organisation declared the Covid-19 pandemic, the Italian government extended regional lockdowns to the whole country (Villani et al., 2021) which saw all social gatherings prohibited, no movement between different regions and all non-essential businesses closed. However, by the 11th of March there were already over 12,000 cases in Italy and over 800 deaths (Ministry of Health 2020b). In May, some restrictions were relaxed and by the 3rd of June, people were allowed to move freely between different regions.

Spain

The first recorded case of Covid-19 in Spain, was on the 31st of January 2020 and the first death was reported on the 13th of February 2020. On the 12th of March, there were just over 3000 confirmed cases of Covid-19 and 87 deaths in Spain, centred on Madrid. By the 13th of March, there were confirmed cases in all regions of Spain. In order to suppress the spread of the virus and in line with governmental regulations, schools and universities were closed for 15 days between the 16th and 30th of March 2020. It was announced that Government.

Ministers were among the 3000 people infected. On the 3rd of April, 950 Spanish residents were declared dead from Covid-19 in a single 24-h period, which was the highest number in the world recorded in a single day at that time. Cases began to decline in May and June 2020.

Germany

Germany was the second European country, after France, to confirm a case of Covid-19, on the 27th of January in Bavaria. By mid to late February, clusters of the virus were reported and on the 9th of March, the first deaths were announced. Schools and universities were closed on the 13th of March. By the middle of March, the federal government and universities agreed that face-to-face teaching would be replaced with digital learning until summer 2021. On the 15th of March, all borders were closed. On the 22nd of March, the German government continued by imposing curfews on residents and by prohibiting physical contact with more than one person from outside their own household. By April 15th 2020, the first phase of relaxing restrictions was announced, which continued throughout May 2020.

United Kingdom

In the UK, the first case of coronavirus was reported on the 31st of January 2020 in York.

Over the next few days, cases were confirmed around the UK and on the 3rd of March the British government revealed their Coronavirus Action Plan, stating that widespread transmission of the virus was highly likely. The first death was recorded on the 5th of March and by the 12th of March supermarkets were forced to limit the purchase of items such as toilet roll and soap, due to bulk buying. On the 16th of March, the Prime Minister advised against non-essential travel and a day later the NHS unveiled their plans to postpone non-urgent operations, to free up over 30,000 hospital beds. By the 20th of March, public venues were closed and three days later lockdown restrictions were announced that saw a stay-at-home order in place for at least three weeks. On the same day, face-to-face teaching on campuses was suspended, in favour of virtual delivery of lectures. Exams were cancelled and graduation ceremonies postponed. Many universities in the UK were criticized for their abrupt response to the pandemic, with some forcing international students to return home with very little notice, many of whom had to travel to countries with poor healthcare systems.

Lockdown restrictions continued into April and May 2020. On the 5th of May, the UK had the second highest daily death toll in the world and a contradictory broadcast was televised, that left the British public confused about rules and restrictions. On the 25th of May, the Prime Minister’s advisor, Dominic Cummings, was caught breaching lockdown rules but by June 2020, lockdown was easing slowly across the country.

The Impact of Covid-19 on University Students

The rapid spread of the coronavirus pandemic, since the first outbreak in Wuhan, China in December 2019, has had a profound effect on university students across the globe (Aristovnik et al., 2020). Already a population who are susceptible to poor mental health (Kross et al., 2013), university students have encountered additional challenges and adversities caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. These have included imminent threats to their personal health, financial strain and uncertainty, risk of unemployment or redundancy, social distancing measures and isolation, loneliness and limited access to basic necessities, such as food and medicine (Wright et al., 2020). In the wider general population, there have been continuous reports of increased depression, anxiety, loneliness, sleeping difficulties, self-harm and suicidal ideation (Fancourt et al., 2020). On top of this, university students have suffered from radical disruption to their learning. Higher education institutions were forced to close, in order to help suppress the spread of the virus. A prolonged closure of face-to-face teaching at universities due to stricter social distancing guidelines, demanded a transition towards a virtual approach to teaching. In fact, over 1.5 billion students were now learning from home (UNESCO, 2020). Educational changes during the pandemic have been associated with a lack of motivation, frustration, boredom and anxiety (Aristovnik et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2020).

A number of students have started sharing their frustrations and stress due to a lack of social contact that has caused elevated levels of anxiety and depression (Huckins et al., 2020). Many have also expressed worry about being far from home, with a large proportion of young adults moving away from home for the first time to attend university. The closure of university campuses has also left students in a moral dilemma, about whether to return home and potentially compromise the health of their loved ones (Zhai & Du, 2020). International students, many of whom have moved to a new country to study at university, typically experience greater isolation, loneliness and reduced overall wellbeing (Burns et al., 2020), further amplified by the Covid-19 pandemic, that prevents them from acclimatising to their new environment. Students living away from home have to encounter the physical, social, financial and psychological struggles caused by Covid-19, without the usual comforts of their social support circles. Not only have university students experienced drastic changes to their everyday life and education, but there is also huge uncertainty about how the pandemic will impact the labour market (Marinoni et al., 2020). Indeed, students are concerned about the repercussions of Covid-19 on their future career prospects (Aristovnik et al., 2020; Browning et al., 2021).

Previous studies on global health epidemics, suggest that long-term psychological issues are inevitable, causing major impact to all aspects of societies over a long period of time (Wright et al., 2020;). It is therefore not surprising that research has increasingly highlighted the detrimental impact that the Covid-19 pandemic has had on the mental health of university students around the world (Browning et al., 2021; Cao et al., 2020; Fancourt et al., 2020) all reporting negative implications including fear, anxiety, stress, loneliness, substance use, binge drinking, weight gain, depression and suicidal ideation. In fact, research has demonstrated that the prevalence of anxiety, depression and other common mental health problems, have been considerably higher in European university students, compared to the general population (Villani et al., 2021). For the most part, empirical research has demonstrated a significant decline in mental health across the university student population (Browning et al., 2021; Villani et al., 2021). Such that, university students are at great risk of poor mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic and beyond. Recent calls have been announced for research to better understand student wellbeing (Burns et al., 2020) and Covid-19 has exacerbated this. Protecting the mental health of university students is of top priority and so the development and delivery of appropriate mental health support services is vital (Zhai & Du, 2020), to help guide and support students through these challenging times and in the future after the pandemic. There are currently insufficient efforts to acknowledge and understand the mental health ramifications of the pandemic on university students. A delayed response could have long-term consequences for students beyond the pandemic (Browning et al., 2021). For educating institutions to support their students efficiently, more needs to be known about the risk factors, and physical, psychological and educational impacts. Research into this is timely and will provide important knowledge that will be beneficial to understand and address key issues during and after the pandemic, to support students in higher education. After all, the Covid-19 pandemic will result in far reaching and long-standing implications for the education and wellbeing of university students (Browning et al., 2021), and will produce major structural changes to higher education (Aristovnik et al., 2020).

Conversely, one study carried out in Germany using a large sample of university students reported no significant differences in general health, stress, and depression between 2019, before the pandemic, and 2020, during the pandemic, (Voltmer et al., 2021). Previous experience of mental illness (Voltmer et al., 2021), along with the presence of cultural factors could promote different mental health effects in students throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. For instance, one study found that the anxiety and depression of university students during the pandemic was most reliant on previous mental health problems as opposed to Covid-19 related factors (Voltmer et al., 2021). Cultural beliefs and values also represent a vital factor towards mental illness. Indeed, a student’s cultural background and belief’s influence their perspective of mental illness and dictates the way in which they describe their own mental health (Satcher, 2001). Factors that are imperative to preventing mental illness such as familial support, help seeking behaviours and availability of mental health resources are also dependent on culture (Satcher, 2001).

The Present Study

Previous research has provided contrasting geographical differences in the way that university students are feeling the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic (Aristovnik et al., 2020). It is important to understand how university students in different parts of the world have been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic and how it has altered their mental health. Diverse student populations make understanding cultural differences a prominent and important matter. Only a small number of research papers have investigated a sample of students from more than one higher education institution (Aristovnik et al., 2020). The current study aimed to highlight what life was like for university students in four different European countries during the first wave of Covid-19. Further, this study aimed to provide a picture of the current state of mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic among university students from the UK, Germany, Italy and Spain. These four countries were carefully selected and were chosen based on the incidence of Covid-19 cases early in the outbreak, numbers of hospitalisations and deaths and also differences in how each countries government was dealing with the outbreak. For instance, the growth of Covid-19 cases was similar in Germany than the other European countries but Germany was reporting less severe impacts. This study also aimed to make comparisons of how university students from the UK, Germany, Italy and Spain perceived different aspects of the Covid-19 pandemic, including fears, loneliness, positive outlook and government responses.

There are three main research questions for this study:

-

(1)

How do perceptions of Covid-19 compare between university students from the UK, Germany, Italy and Spain?

-

(2)

How do mental health outcomes compare between university students from the UK, Germany, Italy and Spain?

-

(3)

How do perceptions of government responses during the Covid-19 pandemic compare between European university students?

Due to the unprecedented nature of Covid-19 and the impact of the outbreak is unparalleled in modern civilisation, it was difficult to predict or hypothesise the outcomes of the study. This research is exploratory in nature and aims to look at how the mental health of university students from these four European countries have been impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Method

Design

This was a cross-sectional study using several standardized measures. This study was conducted using Prolific, an online platform designed to recruit participants whereby they are financially rewarded for taking part in research.

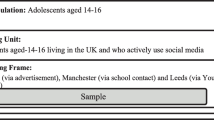

Participants

Participants were 2,006 university students, both male (n = 704) and female (n = 1,289). The majority of participants were between the ages of 18 and 23 (76.2%), with an average age of 23 (M = 22.89). Participants were mostly studying in the UK (n = 1,578), but the sample also included university students from Italy (n = 258), Germany (n = 111) and Spain (n = 58). See Table 1 for a full breakdown of participant demographics. These four countries were selected due to their early involvement in the outbreak of Covid-19 in Europe and the varied government responses to the pandemic. The use of Prolific as a recruitment platform allows you to screen for eligible participants using custom pre-screening criteria. Participants were deemed eligible to take part in the study if they were a university students who were living in either of the selected European countries.

Materials

Attitudes Towards COVID-19 (ATC-19)

This 23-item scale, which measures attitudes towards Covid-19, was developed by the authors. All items were generated using a deductive method of item generation. Items were based on the questions frequently asked of medical professionals in the NHS and previous research into the psychological effects of SARS (Wong et al., 2005). Items generated by the authors were subjected to review by the expert opinion of psychology professors and researchers, frequently used as an accepted analysis of content validity (Ladhari, 2010). Although, a combination of deductive and inductive methods of item generation are preferred (DeVellis, 2003), the unprecedented and rapid advance of Covid-19, rendered it impossible to adopt an inductive method of item generation. Participants rated their responses along a 10-point rating scale, which includes positively and negatively worded items. Exploratory Factor Analysis using a British sample (n = 1,281) of university students (Authors et al. 2020) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis using a European sample of university students (n = 2,006), confirmed the factor structure of the scale. The ATC-19 encompasses three factors: Fears and Anxieties about Covid-19, Positivity during Covid-19 and Loneliness during Covid-19 (Authors et al. 2020). Internal reliability analysis using a sample of British university students (n = 1,281) demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha estimate of 0.75 (Authors et al. 2020) while this study presented a Cronbach’s alpha estimate of 0.67 using a European sample of university students (n = 2,006).

Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE-10)

CORE-10 is a 10-item measure of psychological distress, adapted from the original 34 item CORE-OM (Barkham et al., 2013). This scale is rated on a five-point frequency of occurrence basis, from “not at all” to “most or all of the time,” in response to items such as “I have felt panic or terror” and “I have had difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep”. The reliability and validity of this scale is well tested and widely confirmed, including test–retest reliability, internal consistency reliability and convergent validity (Barkham et al., 2013), as the scale is commonly used in community services and Improving Access to Psychological Therapy (APT) services. Internal reliability of the CORE-10 using the current sample of European students was 0.84.

PERMA-Profiler

The PERMA-Profiler is a 23-item measure of flourishing, developed by Butler and Kern (2016). Total PERMA score consists of five PERMA subscales: positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning and accomplishments, each being measured by three items. This scale also measures physical health, negative emotion, loneliness and overall happiness. This scale is scored on a 10-point rating scale. For example, one item asks “How much of the time do you feel you are making progress towards accomplishing your goals?” with anchors of 0 (“Never”) and 10 (“Always”). This scale has been extensively validated and tested cross-culturally and has consistently shown good internal and cross-time reliability, and good content, convergent and divergent validity (Butler & Kern, 2016). For the overall flourishing score, the internal reliability from this study on Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86.

Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7)

The GAD-7 is a 7-item measure of generalised anxiety that is often used as a screening tool within clinical settings. This scale is rated on a four-point frequency of occurrence basis, from “not at all” to “nearly every day,” on items such as “becoming easily annoyed or irritable”. The GAD-7 has been shown to have good internal reliability as well as good factorial and construct validity (Tiirikainen et al., 2019). Cronbach’s Alpha of the GAD-7 using the present data was 0.89.

Office for National Statistics Subjective Wellbeing Scale (ONS-4)

This is a short, 4-item measure of subjective wellbeing, adapted from the ONS Annual Population Survey (ONS, 2018). Four items focus on life satisfaction, worthwhile life, happiness, and anxiety. For example, one item focused on life worth asks “Overall, to what extent do you feel that the things you do in your life are worthwhile?” The ONS-4 items are scored in the form of a rating scale from 0 (“Not at all”) to 10 (“Completely”). These four well-being questions have been used by the government for a wide range of surveys and have been part of the Annual Population Survey since April 2011 and is shown to be a reliable and valid measure of well-being.

Procedure

First, participants were asked to read some information about the online study and were asked to confirm their written informed consent if they were willing to take part. Participants were made aware that their participation in the research is voluntary. Participants were asked to provide demographic details and were then asked to complete a series of questionnaires. These were the Attitudes towards COVID-19, CORE-10, PERMA-Profiler, GAD-7 and ONS-4. Participants were thanked for their time and were paid £1.50 for 12 min of their time, equating to an hourly rate of £7.50. The survey was open for 2 days, (12th. to 14th. of May 2020), until the survey had received its target of 2,006 responses. At this time, all four European countries were experiencing either regional or nation-wide lockdown restrictions.

Data Analysis

This study aimed to make comparisons of how university students from the UK, Germany, Italy and Spain perceived different aspects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Also, this study aimed to investigate the psychological effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on university students from four different European countries. Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS, version 25). To test the factor structure of the ATC-19 scale using a European sample of university students, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was carried out. Then, a series of one-way non-parametric ANOVAs (Kruskal–Wallis Test) were conducted to determine any geographical differences in attitudes towards Covid-19. Pairwise comparisons using Dunn’s test were calculated to more accurately determine any significant differences between individual countries. Then, to test whether mental health outcomes were different for university students from the UK, Germany, Italy and Spain, a series of one-way between-subjects ANOVA tests were conducted. Finally, a Pearson’s bivariate correlation was carried out to determine whether the extent to which students felt their government was providing effective leadership in relation to Covid-19 was related to numerous mental health outcomes.

Results

To determine whether the research data were normally distributed, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test was used. Gender was non-normally distributed, with skewness of 0.488 (SE = 0.055) and kurtosis of -1.33 (SE = 0.109). The age of participants was normally distributed, with skewness of 0.727 (SE = 0.055) and kurtosis of -0.112 (SE = 0.109).

RQ1—How do Attitudes Towards COVID-19 Compare Between University Students from the UK, Germany, Italy and Spain?

Confirmatory Factor Analysis on the sample of European university students confirmed that the Attitudes towards Covid-19 Scale has three sub-scales: Fears and Anxieties about the Covid-19 pandemic, Positivity during the Covid-19 pandemic and Loneliness during the Covid-19 pandemic. Levene’s test for equality of variances was non-significant for each factor and so equal variances were assumed. Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics for European university students’ responses to each factor.

Analysis was carried out to test whether attitudes towards Covid-19 (Fears and Anxieties about Covid-19, Positivity during Covid-19 and Loneliness during Covid-19) were different for university students from the UK, Germany, Italy and Spain. As the data did not meet the assumption of homogeneity of variance, a series of one-way non-parametric ANOVAs (Kruskal–Wallis Test) were conducted.

Firstly, a Kruskal–Wallis Test revealed significant differences in Fears and Anxieties about Covid-19 scores between the four samples of students, H(3) = 45.161, p < 0.001, demonstrating a weak effect using Epsilon-square (ε2) of 0.02. A post-hoc test using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction indicated that British students’ Fear and Anxieties scores were observed to be significantly higher than German (p = < 0.001) and Italian (p < 0.001) students.

Second, a Kruskal–Wallis Test revealed significant differences in Positivity during Covid-19 scores between students, H(3) = 14.042, p = 0.003, ε2 = 0.01, indicating a weak effect. Dunn’s post hoc test revealed that German students reported increased positivity during Covid-19 when compared to British students (p = 0.002).

Finally, a Kruskal–Wallis Test found significant differences in Loneliness during Covid-19 scores between each sample of students, H(3) = 18.972, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.01. Post hoc analysis using Dunn’s test indicated that Spanish students reported significantly reduced levels of loneliness during Covid-19 when compared to British (p = 0.002) and Italian students (p = 0.028).

RQ2—How Do Mental Health Outcomes Compare Between University Students from the UK, Germany, Italy and Spain?

To test whether mental health outcomes were different for university students from the UK, Germany, Italy and Spain, a series of one-way between-subjects ANOVA tests were conducted. See Table 3 for descriptive statistics of standardised measures used. Prior to conducting an analysis of variance, the assumption of normality was evaluated and determined to be satisfied, as the skewness and kurtosis distributions for all standardised measures were within the ± 1.96 limit, suggesting the departure from normality was not extreme (Field, 2013). Levene’s test for equality of variances was non-significant for psychological distress (0.892), flourishing (0.869), generalised anxiety (0.158), life satisfaction (0.161), life worth (0.059), happiness yesterday (0.304) and anxiety yesterday (0.142), so equal variances were assumed.

Psychological distress

Findings revealed one significant difference between Germany and Italy F(3, 1986) = 4.328, p < 0.05, Hedges g = 0.39, suggesting that Italian students (M = 15.20) scored considerably higher on psychological distress than German students (M = 12.41).

When compared to normative data for CORE-10 captured pre-pandemic (see Table 4), university students in all European countries are suffering from elevated levels of psychological distress, considerably higher than the norm (Barkham et al., 2013).

Flourishing

A one-way ANOVA revealed that there were no significant differences in overall flourishing scores between European students, F(3, 2002) = 1.743, p = 0.156. However, when compared to normative data for the PERMA Profiler (see Table 3), university students in all European countries reported significantly reduced levels of flourishing, considerably lower than the norm (Butler & Kern, 2016).

Generalised Anxiety

Findings from a one-way ANOVA reported a significant difference, F(3, 2002) = 3.324, p < 0.05. Post hoc analysis indicated that German students (M = 6.35) were significantly less anxious than British (M = 7.85), indicating a small effect at g = 0.28, and Italian students (M = 8.12) at p < 0.05, demonstrating a small to medium effect size at g = 0.36. When compared to pre-pandemic normative data for GAD-7 (see Table 3), university students in all European countries reported anxiety levels that markedly exceeded normative scores (Jordan et al., 2017).

Subjective wellbeing

Four separate one-way ANOVAs were conducted on the individual items of the ONS4 scale, measuring subjective wellbeing. There were no significant differences in self-reported scores for life satisfaction, life worth or happiness felt yesterday. On the other hand, there was a significant effect for anxiety felt yesterday, F(3, 2002) = 2.912, p < 0.05. Such that, German university students reported feeling significantly less anxious the previous day (M = 3.98) than Italian students (M = 4.93) at p < 0.05, g = 0.32 indicating a weak to medium effect size. According to the ONS Annual Figures captured pre-pandemic (2019–2020), mean scores for life satisfaction, life worth and happiness were much lower than normative scores, while anxiety scores were considerably higher (see Table 3).

RQ3 – How do European students perceive government responses during the Covid19 pandemic?

An item on the Attitude towards Covid-19 Scale asked participants about the effectiveness of government leadership during the Covid-19 pandemic (see Table 4 for descriptive statistics).

As a higher score indicates a more positive score, it appears that British students were less inclined to believe that their own government was providing effective leadership in relation to Covid-19 (M = 3.5), closely followed by Spain (M = 4.5), Italy (M = 6.2) and then Germany (M = 6.8), who were more supportive of their government’s leadership. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of scores, showing the frequencies of responses for each sample of students. As sample sizes were unequal, percentages of the sample for each response are shown (see Fig. 1).

A Pearson’s bivariate correlation was carried out to determine whether the extent to which students felt their government was providing effective leadership in relation to Covid-19 was related to numerous mental health outcomes. Findings showed that the belief that their government was providing effective leadership during Covid-19 was positively correlated to flourishing (r = 0.141, p < 0.001) and life satisfaction (r = 0.139, p < 0.001), while it was negatively correlated to psychological distress (r = -0.125, p < 0.001) and anxiety (r = -0.091, p < 0.001). The belief that their government was providing effective leadership was also negatively associated with Fears and Anxieties about Covid-19 (r = -0.111, p < 0.001) and positively correlated to Positivity during the Covid-19 pandemic (r = 0.109, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Psychological distress

When compared to pre-pandemic normative scores, the mental health scores for all university students had declined considerably. Indeed, all university students were suffering from elevated levels of psychological distress, considerably higher than the norm. This concurs with research that suggests university students have experienced increased psychological distress since the outbreak of Covid-19 (Authors et al. 2021). Further, previous research indicated that nearly half of working students lost their jobs temporarily or permanently, over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic (Barada et al., 2020). This significantly impairs their ability to cover academic and living costs and is a pivotal risk factor for mental distress. Feeling as though you are losing control over your own health risk management can produce considerable mental distress (Mazza et al., 2020). So, a substantial rise in psychological distress among university students is unsurprising considering the nature of a global health pandemic.

Flourishing

Similarly, university students in all European countries reported significantly reduced levels of flourishing, considerably lower than the norm (Butler & Kern, 2016), supporting recent research (Authors et al. 2020). Disruption to everyday life as we know, along with academic challenges, has potentially compromised the concept of flourishing as students do not have the ability to fulfil the five pillars of the PERMA Model: positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning in life and accomplishment (Seligman, 2011). For instance, graduation ceremonies were among the public events cancelled, which restricted students celebrating their achievements. A dominant force of meaning in life for students is their educational and career focus, which has been completely turned upside down and future implications of the pandemic on the job market are uncertain. Similarly, healthy and satisfying relationships are integral to meaning and overall wellbeing (Seligman, 2011), many of which have been severely impacted.

Anxiety

In addition, all university students reported anxiety levels that markedly exceeded normative scores (Jordan et al., 2017), supporting recent research that has shown increased stress, anxiety and depression in university students around the world (Aristovnik et al., 2020; Browning et al., 2021). Previous research has also shown that anxiety and other common mental health problems, have been higher in university students throughout Europe, when compared to the general population (Villani et al., 2021). On top of the physical, social, emotional and financial challenges felt by university students, which will inevitably raise anxiety levels, there are far-reaching concerns about the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic on the labour market (Marinoni et al., 2020). Damaged career prospects and a great degree of uncertainty about the future will inevitably add to heightened levels of anxiety (Browning et al., 2021).

Wellbeing

Finally, according to the ONS Annual Figures captured pre-pandemic, all scores for life satisfaction, life worth and happiness were much lower and anxiety scores were considerably higher than the norm (ONS Annual Figures, 2019–2020). This coincides with recent research that also demonstrates deteriorated levels of wellbeing in university students (Authors et al., 2021). Current findings support the work of Bradburn (1969), who advocated that wellbeing was the absence of mental health problems (ie. anxiety and psychological distress), as well as the presence of general wellbeing (Diener et al., 2010). An individual’s mental wellbeing is fundamentally shaped and determined by what they value the most and what they consider to be most important to them (McNaught, 2011). Indeed, wellbeing is an individual and existential experience, however family, community and societal wellbeing are often thought to be intrinsically linked to mental health (McNaught, 2011), all of which have been negatively impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Cultural comparisons of university students’ mental health

Psychological distress and anxiety

Findings revealed that Italian students scored considerably higher on psychological distress than German students. These findings gain support from research that confirms a higher prevalence of psychological distress in individuals, who are in close proximity to heavily affected regions (Villani et al., 2021). Indeed, Italy was the first European country affected by Covid-19 and at the time of the study, Italy was experiencing a high incidence of cases and hospitalisations (Ministry of Health 2020b). The rapid spread of the virus alongside a lack of knowledge about the virus, a lack of protective equipment and the absence of testing are all major contributors to distress, anxiety and depression (Villani et al., 2021).

Higher levels of psychological distress among Italian students could, in part, be explained by the significant levels of loneliness reported in Italian students, significantly more so than German students. As Italian students reported significant feelings of loneliness during Covid-19, it is expected that they will experience greater psychological distress, as the two are strongly correlated (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). After all, loneliness in students is directly related to stress, anxiety and depression (Richardson et al., 2017).

Moreover, the current research demonstrates that Spanish students reported significantly reduced levels of loneliness during Covid-19, when compared to British and Italian students. At the time of this study, Spain was trialling a period of eased restrictions and people were free to participate in physical socialisation with family and friends, which helps to explain lower levels of loneliness amongst Spanish students. In comparison, the UK government had recently announced an extension to lockdown, which ordered people to stay at home. Ceased opportunities for interaction, making friends, connection and a considerable deviation from the typical university experience, is likely to cause loneliness (Zhai & Du, 2020) and will have further mental health ramifications (Richardson et al., 2017). After all, social isolation and periods of quarantine are significantly related to loneliness (Mental Health Foundation 2021) and mental health issues (Barada et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2020).

The current research also showed that German students were significantly less anxious and were also less fearful and anxious about the Covid-19 pandemic, particularly compared to British students. Perhaps the snapshot of each country at the time of data collection, particularly the incidence of Covid-19 cases, hospitalisations, restrictions and general unpredictability, can help to explain the fear and anxiety felt by university students. The UK was experiencing a dramatic spike in Covid-19 cases and their government had recently carried out a press conference, when the prime minister announced confusing and contradictory instructions for the British public, which would most likely have added to existing levels of fear and anxiety. False information was being circulated by social media outlets, which amplified fears and anxieties about Covid-19 (Liu et al., 2020) and has proved overwhelming for students (Burns et al., 2020). Comparatively, the German Rectors’ Conference (HRK) was set up in March 2020, to provide German universities with continually updated Covid-19 information and news and how this would affect studying, teaching and research (German Rectors Conference 2021). The different approaches from governments in each country could have major implications to students’ perception of the pandemic and to their mental health. Likewise, the way in which individual universities in each country support their students academically, physically and mentally will likely have massive implications to their wellbeing. Perhaps German students reported less severe mental health impacts compared to those students in other countries because their universities and government were quick to provide effective information and support? There is also evidence that students’ study-related and coping behaviours heavily influence the perception of their physical and mental wellbeing (Voltmer et al., 2012). There needs to be further investigation into how the efforts and support initiatives of universities protect mental health and prevent mental illness in students during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Government responses

Generally, British students reported the worst mental wellbeing. Not only could current findings of immense fear and anxiety about Covid-19 and high levels of loneliness through Covid-19 offer some explanation, but students from the UK were less likely to believe that their government had effectively handled the pandemic. In fact, students from Germany, Italy and Spain believed that their governments’ leadership has been more effective than students from the UK. A study carried out by The Health Foundation (2020), also reported the British general public believed the government had not handled the pandemic well and their belief in the government’s ability to do so, had steadily decreased since May 2020. It is important to note that younger people, between the ages of 18 and 24, were even less likely to believe (30%) that the government has responded well to the pandemic (The Health Foundation 2020). This is unsurprising when taking into consideration the release of vague and contradictory rules and regulations, along with the recent public scandal that saw the Prime Minister’s advisor caught breaking the newly imposed travel and social distancing restrictions. Indeed, research suggested that around half of the British public thought that governmental measures in response to Covid-19 were simply not enough, with much of the public stating that governmental guidance and advice was not clear (The Health Foundation 2020).

While governments around the world have developed key measures to suppress the impact of the virus, research has highlighted a growing sense of mistrust and increasing levels of dissatisfaction among younger generations, with the way in which their governments have responded to the pandemic (Aksoy et al., 2020). Each nation has dealt and responded to Covid-19 differently with governments enforcing varying iterations of social distancing and quarantine measures. Indeed, varying governmental responses during Covid-19 were expected to contribute to differing risks and outcomes (Germani et al., 2020). The current study expands on this by evidencing that university students’ belief that their government was providing effective leadership during Covid-19, was correlated with positivity during the Covid-19 pandemic, flourishing and life satisfaction. Similarly, the belief that their government was providing effective leadership during Covid-19, was negatively correlated with fears and anxieties about Covid-19, psychological distress and anxiety. There is concern about how these eroding feelings of trust towards political leaders among younger people could cause long-term implications.

These findings can offer some explanation as to why British university students are experiencing some of the worst outcomes, such as increased fear and anxiety about Covid-19, loneliness during Covid-19, elevated levels of anxiety and deteriorated wellbeing. Students’ perceptions that their government has not effectively responded to the pandemic and a lack of transparency, has sapped public trust (Aksoy et al., 2020). Also, these findings may also explain why German students are not suffering from the same intense levels of mental distress? They show the importance of governmental response in suppressing the inevitable mental health implications on students during a global health pandemic, such as Covid-19. In fact, there have been recent announcements that Germany is becoming an increasingly popular destination choice for studying, due to praise for their ongoing Covid-19 response (Quinn, 2020).

Positivity during Covid-19

German students also reported the greatest level of positivity during Covid-19. At the time of data collection (May 2020), Germany was in the middle of its first phase of easing restrictions, which would undoubtedly boost feelings of positivity, even if only temporarily. A significantly more positive outlook on the Covid-19 pandemic could, in part, be explained by the considerably better mental health witnessed amongst German university students. German students were experiencing the least drastic mental health outcomes, and wellbeing is strongly linked to attitudes towards life and general outlook on life (Burns et al., 2020), which paradoxically then enhances wellbeing. Most likely, there is a cyclic relationship between positive outlook during Covid-19 and wellbeing, whereby each positively influences the other. Maintaining a positive outlook during challenging times could be incredibly important for alleviating severe mental distress and encouraging improved outcomes.

Moreover, recent evidence indicates the importance of perspective and mind-set towards social distancing and isolation efforts. Indeed, it was found that people who perceived their efforts to stay home as ‘confinement,’ suffered more psychologically compared to those who perceived it as a responsibility or an opportunity (Bozdağ, 2021). Further exploration into how positivity during Covid-19 can be a protective factor against more serious mental health issues is a worthwhile pursuit.

It could also be argued that the governmental response and information and support available to German students early in the pandemic could be better equipped them and helped to prevent subsequent fear, worry and anxiety about the pandemic and further reducing severe mental health effects. German students fared significantly better on every single mental health outcome. They also reported less negative (i.e. fear, anxiety and loneliness) and more positive perceptions of the Covid-19 pandemic. The exact reasoning behind this is unknown, but remains worthwhile for further investigation as German students consistently scored better on all accounts compared to university students from the UK, Italy and Spain. A number of factors, internal and external to the students will have impacted their self-reported mental health, most likely having interactive effects with each other. For instance, promise in their governments response to the pandemic along with timely and clear guidance, endorsement of available resources and effective media use and consumption could prevent fear, anxiety and worry about the pandemic and encourage a positive perspective. In turn, these factors are likely to further help protect students from severe mental distress and shield them from a vicious cycle whereby each adds fuel to the downward spiral. It is also likely that cultural factors are at play. Cultural beliefs and values also represent a vital factor towards mental illness. Indeed, a student’s cultural background and belief’s influence their perspective of mental illness and dictates the way in which they describe their own mental health (Satcher, 2001). Factors that are imperative to preventing mental illness such as familial support, value orientations, help seeking behaviours, media consumptions and availability of mental health resources are also dependent on culture (Germani et al., 2020). University students’ cultural backgrounds can likely help to prevent mental illness, or comparatively generate mental illness during the Covid-19 pandemic and beyond.

Limitations

There are limitations to the current study. First of all, it adopted a cross-sectional design, which prevents causal interpretations to be drawn which calls for more longitudinal and qualitative research in this area. Additionally, self-report measures were used which are often confounded with social desirability (Phillips & Clancy, 1972). However, standardised measures were used that have had extensive reliability and validity testing. Participants were recruited online, as this was deemed more appropriate amidst a global health pandemic and also enabled greater and quicker access to university students in different European countries. The survey was published on Prolific in English, which could offer some explanation as to why there was some sample skew and some under representation from other European countries. The study was carried out over 2 days in May 2020 where various stages of the Covid-19 pandemic were progressing in participating countries. For instance, it was more advanced in some regions that in others with varying degrees of magnitude, which could affect the findings. Finally, university students’ perceptions and wellbeing captured in this study are not simply a reflection of the pandemic and their geographic differences but are likely constituted by other factors such as politics, economic development, cultural background and religion (Aristovnik et al., 2020).

Practical implications and future directions

Students at university must now contend with the physical, mental, social, financial and academic implications, of the Covid-19 pandemic. Uptake of mental health support services has steadily increased over recent years and Covid-19 has caused growing demand and pressure on support services (Burns et al., 2020). Current findings demonstrate the dire need for widespread, readily available support measures that help students to cope with the stress, anxiety and loneliness throughout the pandemic and beyond. Access to health and wellbeing services is vital and must be expanded and adapted to meet the evolving physical, emotional and social needs of university students. A combination of extensive disruptions to previous academic life alongside governmental actions to suppress the spread of the virus (i.e. lockdowns, social distancing, travel bans) will undoubtedly cause widespread and long lasting psychological impacts (Cao et al., 2020). Understanding the long-term impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on university students is essential.

It remains uncertain how educational changes and challenges are influencing the mental health of university students, although it is likely to be significant risk factor. Previous research has shown that disruption to education can produce a variety of issues related to reduced motivation, loss of independence and detrimental effects on self-identity and mental health, which all limit the growth of students (Cao et al., 2020). There is a strong relationship between academic attainment and wellbeing (Authors et al. 2020), which contributes toward economic, social and ecological growth in communities. There is also the realistic expectation, that current and prospective university students will have to transition into a ‘re-imagined’ approach to learning, following the trials and tribulations throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, which remain ambiguous as to what form this will take? Monitoring how the Covid-19 pandemic has affected the structure of higher education, teaching modalities, learning, associated behaviours and future prospects, should be a priority.

Government responses to Covid-19 play a significant role in determining university students’ perceptions and experiences of the pandemic as well as their mental health. Moreover, the way in which a government deals with global health emergencies is fundamental to general health and wellbeing and these findings should help to inform future strategies and decision-making in the event of another health pandemic. The Italian government announced new support measures for university students, to seek extra funding to cover certain financial implications caused by Covid-19, alongside emergency financial grants for course-related costs for economically disadvantaged students. However, it is unclear how much support measures such as these alleviate mental distress and promote wellbeing. Also, what about the role of the university in supporting students? How do the support measures developed by universities prevent mental distress and promote mental wellbeing in universities? Longitudinal and qualitative investigation could help to provide a clear picture as to how such initiatives are advantageous to the target population and inform future strategies.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not Applicable.

References

Aksoy, C., Ganslmeier, M., & Poutvaara, P. (2020). Public attention and policy responses to COVID-19 pandemic. CESifo Working Paper No. 8409, Available at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3646852

Aristovnik, A., Keržič, D., Ravšelj, D., Tomaževič, N., & Umek, L. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability, 12(20), 8438.

Authors et al. (2020)

Authors et al (2021)

Barada, V., Doolan, K., Burić, I., Krolo, K., & Tonković, Ž. (2020). Student life during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: Europe-Wide Insights. University of Zadar.

Barkham, M., Bewick, B., Mullin, T., Gilbody, S., Connell, J., Cahill, J., & Evans, C. (2013). The CORE 10: A short measure of psychological distress for routine use in the psychological therapies. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 13(1), 3–13.

Bozdağ, F. (2021). The psychological effects of staying home due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of General Psychology, 1–23.

Bradburn, N. M. (1969). The Structure of Psychological Well-Being. Aldine Publishing Co.

Browning, M., Larson, L. R., Sharaievska, I., Rigolon, A., McAnirlin, O., Mullenbach, L., Cloutier, S., Vu, T. M., Thomsen, J., Reigner, N., Metcalf, E. C., D’Antonio, A., Helbich, M., Bratman, G. N., & Alvarez, H. O. (2021). Psychological impacts from COVID-19 among university students: Risk factors across seven states in the United States. PLoS One, 16(1), e0245327. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245327

Burns, D., Dagnall, N., & Holt, M. (2020, October). Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student wellbeing at universities in the United Kingdom: A conceptual analysis. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 5, p. 204). Frontiers.

Butler, J., & Kern, M. L. (2016). The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 6(3).

Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

DeVellis, R. F. (2003). Scale development: Theory and applications. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D. W., Oishi, S., & BiswasDiener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2021). COVID-19 situation update worldwide, as of week 26, updated 8 July 2021. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. (2021, July 8). https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographicaldistribution-2019-ncov-cases.

Fancourt, D., Steptoe, A., & Bu, F. (2020). Trajectories of depression and anxiety during enforced isolation due to COVID-19: Longitudinal analyses of 59,318 adults in the UK with and without diagnosed mental illness. medRxiv.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). Sage.

German Rectors Conference (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and the German universities. Deutsche Website. https://www.hrk.de/activities/the-covid-19-pandemicand-the-german-universities/.

Germani, A., Buratta, L., Delvecchio, E., & Mazzeschi, C. (2020). Emerging adults and COVID-19: The role of individualism-collectivism on perceived risks and psychological maladjustment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3497. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103497

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Huckins, J. F., daSilva, A. W., Wang, W., Hedlund, E., Rogers, C., Nepal, S. K., Wu, J., Obuchi, M., Murphy, E. I., Meyer, M. L., Wagner, D. D., Holtzheimer, P. E., & Campbell, A. T. (2020). Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e20185. https://doi.org/10.2196/20185

Jordan, P., Shedden-Mora, M. C., & Löwe, B. (2017). Psychometric analysis of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) in primary care using modern item response theory. PloS One, 12(8), e0182162.

Kross, E., Verduyn, P., Demiralp, E., Park, J., Lee, D. S., Lin, N., & Ybarra, O. (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PloS One, 8(8), e69841.

Ladhari, R. (2010). Developing e-service quality scales: A literature review. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 17(6), 464–477.

Liu, Q., Zheng, Z., Zheng, J., Chen, Q., Liu, G., Chen, S., Chu, B., Zhu, H., Akinwunmi, B., Huang, J., Zhang, C., & Ming, W. K. (2020). Health communication through news media during the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in China: Digital topic modeling approach. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(4), e19118. https://doi.org/10.2196/19118

Marinoni, G., Van’t Land, H., & Jensen, T. (2020). The impact of Covid-19 on higher education around the world. IAU Global Survey Report.

Mazza, C., Ricci, E., Biondi, S., Colasanti, M., Ferracuti, S., Napoli, C., & Roma, P. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Immediate psychological responses and associated factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3165.

McNaught, A. (2011). Defining wellbeing. In A. McNaught & A. Knight (Eds.), Understanding Wellbeing: An Introduction for Students and Practitioners of Health and Social Care (pp. 7–22). Scion Publishing.

Mental Health Foundation. (2021, March 22). Pandemic one year on: LANDMARK mental health study Reveals mixed picture. Retrieved July 10, 2021, from https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/news/pandemic-one-year-landmark-mental-healthstudy-reveals-mixed-picture

Ministry of Health. (2020b). Covid-19: i casi in Italia alle ore 18 del 11 Marzo (Covid-19: the cases in Italy at 18:00 in March 18). http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/news/p3_2_1_1_1.jsp?lingua=italiano&menu=n otizie&p=dalministero&id=4204

Office for National Statistics (2018). Personal wellbeing user guidance. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/methodologies/personalwellbeingsurveyuserguide

Phillips, D. L., & Clancy, K. J. (1972). Some effects of ‘social desirability’ in survey studies. American Journal of Sociology, 77(5), 921–940.

Quinn, C. (2020, April 24). Interest in studying in Germany grows as Covid-19 response praised. THE PIE NEWS: News and business analysis for Professionals in International Education. https://thepienews.com/news/interest-studying-in-germanygrows-as-covid-19-response-praised/.

Richardson, T., Elliott, P., & Roberts, R. (2017). Relationship between loneliness and mental health in students. Journal of Public Mental Health, 16, 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH03-2016-0013

Sanfelici, M. (2020). The Italian Response to the COVID-19 Crisis: Lessons Learned and Future Direction in Social Development. The International Journal of Community and Social Development, 2(2), 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/2516602620936037

Satcher, D. (2001). Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity—A supplement to mental health: A report of the surgeon general. US Department of Health and Human Services.

Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. PsycNET.

The Health Foundation. (2020, September 29). What the public thinks – another five things we learnt from our COVID-19 polling. https://www.health.org.uk/news-andcomment/newsletter-features/what-the-public-thinks-another-five-things-we-learnt.

Tiirikainen, K., Haravuori, H., Ranta, K., Kaltiala-Heino, R., & Marttunen, M. (2019). Psychometric properties of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) in a large representative sample of Finnish adolescents. Psychiatry Research, 272, 3035.

UNESCO. Covid-19 Impact on Education. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed on 28 July 2020).

Villani, L., Pastorino, R., Molinari, E., Anelli, F., Ricciardi, W., Graffigna, G., & Boccia, S. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological well-being of students in an Italian university: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 1–14.

Voltmer, E., Kötter, T., & Spahn, C. (2012). Perceived medical school stress and the development of behavior and experience patterns in German medical students. Medical Teacher, 34(10), 840–847.

Voltmer, E., Köslich-Strumann, S., Walther, A., Kasem, M., Obst, K., & Kötter, T. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on stress, mental health and coping behavior in German University students–a longitudinal study before and after the onset of the pandemic. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–15.

Wong, T. W., Yau, J. K., Chan, C. L., Kwong, R. S., Ho, S. M., Lau, C. C., & Lit, C. H. (2005). The psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on healthcare workers in emergency departments and how they cope. European Journal of Emergency Medicine, 12(1), 13–18.

Wright, K. P., Jr., Linton, S. K., Withrow, D., Casiraghi, L., Lanza, S. M., de la Iglesia, H., & Depner, C. M. (2020). Sleep in university students prior to and during COVID-19 stay-at-home orders. Current Biology, 30(14), R797–R798.

Zhai, Y., & Du, X. (2020). Addressing collegiate mental health amid COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Research, 288, 113003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113003

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from Research England and the University of Bolton.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study, with CK going on to secure funding to conduct the research. MV led on the design of the Attitudes Towards Covid-19 scale, with support and refinement from CK and JC. RA led on participant recruitment, data collection and data analysis, with support from CK and JC. RA led on drafting the paper with support and refinements from CK and JC.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was obtained in line with British Psychological Society guidelines.

Consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Current Themes of Research:

Impacts of Covid-19 on university students well-being and education; Academic tenacity; Grit; Resilience; Wellbeing; Flourishing; Employability

Most Relevant Publications:

• Kannangara C. S., Allen R. E., Waugh G., Nahar N., Khan S., Rogerson S., & Carson, J. (2018). All that glitters is not grit: Three studies of grit in university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, https://doi.org/10. 3389/fpsych.2018.01539

• Kannangara, C. S., Allen, R. E., Carson, J. F., Khan, S. Z. N., Waugh, G., & Kandadi, K. R. (2020) Onwards and upwards: The development, piloting and validation of a new measure of academic tenacity- The Bolton Uni-Stride Scale (BUSS). PLoS ONE, 15(7): e0235157.

• Allen, R. E., Kannangara, C., & Carson, J. (2021). True grit: How important is the concept of grit for education? a narrative literature review. International Journal of Educational Psychology: IJEP, 10(1), 73-87.

• Kannangara, C., Allen, R., Vyas, M. & Carson, J. (2021). Every cloud has a silver lining: Short-term psychological effects of Covid-19 on British university students. Manuscript submitted for publication.

• Kannangara, C., Allen, R. & Carson, J. (2021). An International Validation of the Bolton Unistride Scale (BUSS) of Academic Tenacity. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, R., Kannangara, C., Vyas, M. et al. European university students’ mental health during Covid-19: Exploring attitudes towards Covid-19 and governmental response. Curr Psychol 42, 20165–20178 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02854-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02854-0