Abstract

A few studies have indicated that adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are more inclined to ruminate than adults in the general population. The present study examined whether subclinical ASD symptoms including difficulties in social interaction and attention to detail and ADHD symptoms that were composed of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity were related to depressive rumination in undergraduate students. This study also examined whether rumination is a mediating factor in the relationship of ASD and ADHD symptoms with depression. Non-clinical undergraduate students (N = 294) in Japan completed the Autism-Spectrum Quotient, Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, interpersonal conflict subscale of the Interpersonal Stress Event Scale, Ruminative Responses Scale, and Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition. Structural equation modeling indicated that hyperactivity-impulsivity was positively associated with rumination both directly and indirectly via interpersonal conflict, and that attention to detail and inattention were directly and positively related to rumination. The significant relationship between difficulties in social interaction and rumination disappeared after controlling for the influence of depression. These findings indicated that one pathway through which hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms prolong rumination might be through the increase in interpersonal conflict. In addition, it is possible that cognitive inflexibility, academic difficulties, and adverse driving outcomes caused by attention to detail, inattention as well as hyperactivity-impulsivity may lead to rumination. Moreover, attention to detail, inattention, and hyperactivity-impulsivity indirectly increased depression via rumination, indicating that rumination is an important mediator in the relationship of subclinical ASD and ADHD symptoms with depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are two major types of neurodevelopmental disorders. ASD is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction, as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviors, interests, or activities. On the other hand, ADHD is characterized by, as its name suggests, a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Although they manifest early in development, their symptoms can persist into adulthood among individuals with ASD (Farley et al. 2009; Howlin et al. 2004) and ADHD (Mannuzza et al. 2011; Uchida et al. 2018). Moreover, adults in the general population exhibit ASD and ADHD symptoms at a subclinical level (Baron-Cohen et al. 2001; Kessler et al. 2005).

It is well known that individuals with ASD and ADHD are frequently diagnosed with depressive disorders (Kessler et al. 2006; Lever and Geurts 2016). In addition, previous studies have indicated that adults with higher scores for subclinical ASD and ADHD symptoms also have higher depressive symptoms (Rosbrook and Whittingham 2010; Kanai et al. 2011; McKinney et al. 2013; Takeda et al. 2017). However, the reason for this is unclear. The purpose of the present study was to examine whether relationships between subclinical ASD and ADHD symptoms and depressive symptoms in undergraduate students were mediated by depressive rumination, which is a robust predictor of depression.

There are several scales that assess subclinical ASD and ADHD symptoms. The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ) is a widely used self-report measure to assess autistic traits that was developed by Baron-Cohen et al. (2001). AQ was initially consisted of five subscales, namely social skill, attention switching, attention to detail, communication, and imagination (Baron-Cohen et al. 2001). However, Hoekstra et al. (2008) suggested that the subscales excluding attention to detail were highly correlated and clustered together into social interaction (i.e., unwillingness to approach social situations, difficulties in communication with others, and deficits in empathetic abilities). Although other factor structures of AQ have been proposed (Austin 2005; Hurst et al. 2007; Stewart and Austin 2009; Kloosterman et al. 2011; Lau et al. 2013), the two-factor model proposed by Hoekstra et al. (2008) has the advantage of being more parsimonious than the other models to facilitate multivariate analysis. Furthermore, the two-factor model overlaps with the cardinal symptoms of ASD described in DSM-5. The social interaction subscale of the model corresponds with persistent deficits in social communication and social interactions, and the attention to detail subscale (i.e., a preference for details and patterns) might reflect circumscribed interests and increased perception of auditory and visual stimuli, which is a subset of restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviors, interests, or activities.Footnote 1 Furthermore, the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS; Kessler et al. 2005) has been used to assess subclinical symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity. The two subscales correspond to criterion A DSM-5 categories for diagnosing ADHD.

One possible mediator of the relationship of ASD and ADHD symptoms with depressive symptoms could be depressive rumination, which is defined as “behaviors and thoughts that focus one’s attention on one’s depressive symptoms and on the implications of these symptoms” (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991, p. 569). Crane et al. (2013) demonstrated that adults with ASD ruminate more frequently than non-ASD counterparts. Also, higher mean scores on the Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS; Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 1991) than the general population (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 1999) was reported among ADHD adults (Oddo et al. 2018).Footnote 2 Because previous experimental and longitudinal studies have robustly demonstrated that rumination intensifies depressive symptoms and predicts the onset and relapse of major depressive episodes (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008, for review), it is plausible that rumination mediates the relationship of ASD and ADHD with depressive disorders. Consistent with this notion, rumination was positively correlated with concurrent depressive symptoms among adult ASD group (Crane et al. 2013; Gotham et al. 2014), and adult ADHD group with comorbid lifetime depressive disorders ruminates more frequently than those without comorbid depression (Oddo et al. 2018).

Burrows et al. (2017) reviewed previous findings and proposed that negative self-referential processing and cognitive inflexibility (i.e., the inability to adaptively switch between mental processes to produce appropriate behavioral responses) in ASD increase the risk of rumination. A recent meta-analysis related to the proposal by Burrows et al. (2017) showed that impaired set-shifting component of executive function is associated with rumination (Yang et al. 2017). In addition, it is plausible that difficulties in social interaction that are common in ASD, as well as aggressive behaviors caused by higher hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms of ADHD (Theriault and Holmberg 2001; Vierikko et al. 2004), might generate interpersonal conflict, leading to sustained rumination. Interpersonal conflict is a type of interpersonal stressor that includes quarrels with an acquaintance, being insulted by others, and disagreements with an acquaintance (Hashimoto 1997). According to the goal progress theory of rumination (Martin et al. 2004), stressors can keep one’s goals unattained and lead to rumination about information related to the goals that have not yet been attained or progressed toward (See Michl et al. 2013 for other possible reasons why exposure to stressors can increase rumination). In line with this theory, previous studies have demonstrated that frequent exposure to stressors including those in the interpersonal domain is concurrently and prospectively associated with increased rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 1994; Moberly and Watkins 2008a; Michl et al. 2013). Therefore, it is plausible that increased interpersonal conflict caused by difficulties in social interaction and hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms could prolong rumination. These are the possible reasons why individuals with ASD and ADHD ruminate frequently.

It was predicted that individuals with more ASD and ADHD symptoms at the subclinical level would ruminate frequently due to the same reasons. To our knowledge, there was only one study that examined and showed a positive relationship between autistic traits and depressive rumination in the general population (Keenan et al. in press), and no study to date has investigated whether subclinical inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms were related to depressive rumination. Furthermore, previous studies did not compare the influences of ASD and ADHD symptoms on rumination in non-clinical as well as clinical samples. Because ASD and ADHD symptoms were moderately correlated with each other (e.g., Reiersen et al. 2008; Polderman et al. 2014), it is important to examine what subcomponent of ASD and ADHD symptoms is critically associated with rumination.

The current study was designed to examine whether social interaction and attention to detail in autistic traits, as well as subclinical inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity in ADHD, were related to rumination directly or indirectly via interpersonal conflict. The study also investigated if rumination mediated the association between these symptoms and depression. It is known that rumination and depression have a mutually enhancing relationship (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 1999; Moberly and Watkins 2008b). Therefore, it is possible that depression is a confounding factor in the association of ASD and ADHD symptoms with rumination. Consequently, we examined these associations after controlling for the influence of depression. Furthermore, we also analyzed a model that included two subtypes of rumination, namely brooding and reflection than rumination in general. Brooding is a maladaptive aspect of rumination that predicts increases in depression, whereas reflection is assumed to be an adaptive or less maladaptive aspect of rumination that has been longitudinally associated with less depression or no such association (Treynor et al. 2003; Schoofs et al. 2010). We examined whether social interaction, attention to detail, inattention, and hyperactivity-impulsivity were related to the two subtypes of rumination to identify the subtypes through which these symptoms were related to depression.

Methods

Participants

Japanese undergraduate students (n = 351) were recruited from the Tokai Gakuin University and Aichi Gakuin University in Japan mainly during psychology lectures. They took part in this study between November 2016 and January 2017. Data of 57 students were excluded because of missing values, and therefore, the final sample was composed of 294 participants (97 men, 197 women, mean age 20.17, SD = 2.75; age range = 18 to 54 years). All participated in the study voluntarily. These participants completed the questionnaires described below. The Ethics Committee of Tokai Gakuin University approved the study.

Measures

Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ; Baron-Cohen et al. 2001)

This scale is a self-report measure that assesses autistic traits in adults. In the present study, the Japanese translation by Wakabayashi et al. (2004) was used. The AQ includes 50 items, each of which is rated on a 4-point rating scale anchored between 1 (definitely disagree) and 4 (definitely agree). In the scoring system devised by Baron-Cohen et al. (2001), items are scored as 1 for a response in the autistic direction and 0 for a non-autistic response. However, the present study treated the response scale as a four-point Likert scale following the scoring method devised by Austin (2005) and Hoekstra et al. (2007), because this method yields more variance than the 0/1 scoring system, and therefore facilitates detecting associations between subscales of the AQ and other measures.

Although the AQ is initially designed with five subscales in which each subscale is composed of ten items (Baron-Cohen et al. 2001), Hoekstra et al. (2008) indicated that subscales of the AQ excluding attention to detail are composed of one superordinate factor, social interaction. Consistent with the implications indicated by Hoekstra et al. (2008), the present data showed moderate positive correlations among social skills, attention switching, communication, and imagination (r ranged from .16 to .53). Moreover, correlations between these four subscales and attention to detail were nonsignificant or negative (r ranged from .00 to −.27). Therefore, in the present study, the scores of the 40 items that compose subscales excluding attention to detail were summed up and were considered as the social interaction subscale. This decision was also justified because the internal consistencies of the social interaction subscale was satisfactory (α = .81), even though the four subscales that compose social interaction were in the low to moderate range (αs = .77, .37, .64, .47 for social skill, attention switching, communication, and imagination, respectively). Internal consistency of the attention to detail subscale was .54.

Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS; Kessler et al. 2005)

The ASRS is a self-report measure designed to assess ADHD symptoms in adults. This scale is composed of 18 items that represent the DSM-IV Criterion A symptoms and consists of two subscales, inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity. Each question asks how often a symptom occurred over the past six months, and is rated on a 5-point rating scale anchored between 0 (never) and 4 (very often). The Japanese translation by Takeda et al. (2017) was used. Internal consistencies of the inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity subscales were respectively .80 and .84, in this study.

Interpersonal Stress Event Scale (Hashimoto 1997)

This scale is a reliable and valid measure that assesses the frequencies of interpersonal stressors that are often encountered in daily life by Japanese young adults. Although this scale includes three subscales, only the interpersonal conflict subscale (composed of 9 items) was used in this study. Sample items of this subscale include “I quarreled with my acquaintance,” “I was insulted by others,” and “I disagreed with my acquaintance.” Participants indicated how often they encountered each event over the past three months on a 4-point scale anchored between 1 (not at all) and 4 (often). Internal consistency of the interpersonal conflict subscale was .91.

Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS; Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 1991)

The RRS is a widely used self-report measure of depressive rumination. This scale includes 22 items, each of which is rated on a 4-point rating scale anchored between 1 (almost never) and 4 (almost always). The RRS consists of five items assessing brooding, five items assessing reflection, and 12 depression-related items. Brooding and reflection subscale scores and total RRS scores were calculated. Adequate psychometric properties of the RRS, including good internal consistency and construct validity, as well as moderate test-retest reliability for total and subscale scores have been reported (Treynor et al. 2003; Schoofs et al. 2010). The Japanese translation by Hasegawa (2013) was used. Internal consistencies of the brooding and reflection subscales and RRS total scale were .84, .80, and .95, respectively.

Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II; Beck et al. 1996)

This scale is a well-validated 21-item self-report questionnaire that measures the severity of depressive symptoms experienced in the past two weeks. Participants rate their responses using a 0–3 scale, with higher scores indicating greater severity of depression. The Japanese translation by Kojima and Furukawa (2003) was used. Internal consistency of the BDI-II was .93.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses except for structural equation modeling were performed using SPSS ver. 23 and structural equation modeling was conducted by Amos ver. 23. Raw scores for each variable were analyzed, and Zero-order Pearson’s correlations were computed between each measure. Structural equation modeling using the maximum likelihood method was conducted to examine how autistic traits, inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms influenced depression. In these analyses, total scale and subscale scores were treated as observable variables.

Results

Table 1 displays descriptive statics of each measure. As shown in Table 1, all measures were normally distributed. Table 2 shows correlations between each of the measures. Although the correlation between inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity was relatively high (r = .60), other correlations among each variable were in the small to moderate ranges, indicating that the problem of multicollinearity would be unlikely when conducting multivariate analyses.

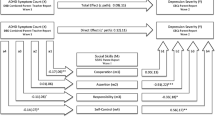

Structural equation modeling was conducted with social interaction, attention to detail, inattention, and hyperactivity-impulsivity as independent variables, interpersonal conflict, and rumination assessed by total RRS scores as mediators (interpersonal conflict was assumed to intensify rumination), and depression assessed by the BDI-II score as a dependent variable. In addition, the direct paths from four independent variables to rumination and depression were set. Furthermore, we set the paths from gender (1 = male, 2 = female) and age to interpersonal conflict, rumination, and depression to control for the influences of gender and age. Only a few significant effects of gender and age were identified on each endogenous variable, and therefore these results were not described. All exogeneous variable were correlated. This model had an excellent fit for the data: χ2 (1) = .15, p = .70; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00. Figure 1 shows standardized coefficients in the model. It can be seen that interpersonal conflict increased rumination and in turn intensified depression. Inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity were positively associated with interpersonal conflict, and all independent variables were positively related to rumination. In addition, social interaction and hyperactivity-impulsivity were directly and positively associated with depression. Each variable explained 20.3% of the variances for interpersonal conflict, 37.0% of the variances for rumination,33.2% of the variances for depression.

The results of a model examining how ASD and ADHD symptoms influence rumination and depression. For clarity, paths from gender and age to the other variables, nonsignificant paths, error variables, and covariances are not depicted. The coefficients after controlling for the influences of depression are depicted in parentheses. RRS = Ruminative Responses Scale; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition; *p < .05, **p < .01, *** p < .001

A bias-corrected bootstrap with 10,000 bootstrap re-samples was conducted to determine the significance of indirect effects. The results indicated that only hyperactivity-impulsivity was indirectly associated with rumination via interpersonal conflict (β = .08, 95% CI: [.03, .14], p < .001). Furthermore, all independent variables were indirectly and positively related with depression via two mediators. The standardized coefficients of total indirect effects from four variables were .05 (95% CI: [.01, .09], p = .01) for social interaction, .06 (95% CI: [.03, .11], p < .001) for attention to detail, .09 (95% CI: [.04, .15], p < .001) for inattention, and .09 (95% CI: [.05, .15], p < .001) for hyperactivity-impulsivity.

We also conducted structural equation modeling with depression as an exogeneous variable that influences interpersonal conflict and rumination instead as a dependent variable, because it is possible that depression might be a confounding factor in the relationship between other variables. This model was just identified (zero degrees of freedom), so there was no test of overall model fit. Standardized coefficients in the model are displayed within parentheses in Fig. 1. It can be seen that nearly all significant coefficients were unchanged, whereas the significant coefficient of social interaction to rumination disappeared.

Next, we conducted an analysis of the model that included brooding and reflection subscales instead of the RRS total scale. This model had an excellent fit for the data: χ2 (1) = .63, p = .43; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00. Results indicated that the relationships between brooding and the other variables were very similar to the findings shown in Fig. 1. In brief, social interaction, attention to detail, inattention, hyperactivity-impulsivity as well as interpersonal conflict were directly associated with brooding (βs ranged from .11 to .26, ps < .05), and hyperactivity-impulsivity was indirectly associated with brooding via interpersonal conflict (β = .06, 95% CI: [.03, .12], p < .001). On the other hand, attention to detail, inattention, hyperactivity-impulsivity and interpersonal conflict were directly associated with reflection (βs ranged from .13 to .27, ps < .05), and hyperactivity-impulsivity was indirectly associated with reflection via interpersonal conflict (β = .08, 95% CI: [.04, .14], p < .001). Also, social interaction, inattention, and hyperactivity-impulsivity were indirectly related to depression (βs ranged from .04 to .09, ps < .05) although indirect association of attention to detail with depression was slightly weak and not significant (β = .04, 95% CI: [−.01, .09], p = .11). Because brooding, but not reflection was significantly related to depression (β = .35, p < .001, β = −.04, p = .56, respectively), it seems that these indirect effects appear as a result of brooding.

Discussion

The present study examined whether ASD and ADHD symptoms were related to depressive rumination directly and indirectly via interpersonal conflict. This study also examined whether rumination is a mediating factor in the relationship of ASD and ADHD symptoms with depression. This study was a cross-sectional study, and therefore conclusions about causality should be made with caution. However, the results of the study indicated the processes by which subclinical ASD and ADHD symptoms are associated with depression.

Results indicated that hyperactivity-impulsivity was positively associated with rumination that was assessed by using the total RRS scores both directly and indirectly via interpersonal conflict. Moreover, attention to detail and inattention were directly and positively associated with rumination. Also, these three traits were related to depression indirectly via rumination (and interpersonal conflict). The significant relationship between social interaction and rumination disappeared after controlling for the influences of depression, indicating that depression was a confounding factor in this relationship.

Hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms are known to be strongly associated with aggressive behaviors (Theriault and Holmberg 2001; Vierikko et al. 2004). Therefore, it is plausible that behaviors caused by symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity generate interpersonal conflict which is a social stressor. Increased exposure to interpersonal conflict might lead to sustained rumination about problems or the self because stressors can keep a person’s goals unattained and lead to rumination about information related to the unattained goals (Martin et al. 2004).

On the other hand, the results of structural equation modeling indicated that difficulties in social interaction in autistic traits were not related to interpersonal conflict, although this subdimension is significantly and positively correlated with interpersonal conflict (r = .18). The social interaction subscale was positively correlated with hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms, and this subscale was not associated with interpersonal conflict after controlling for hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms and other ASD and ADHD symptoms. Therefore, the simple correlation between difficulties in social interaction and interpersonal conflict could be due to confounding by hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms (More specifically, aggressive behaviors caused by hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms).Footnote 3 The present findings that show significant correlations between subclinical ASD and ADHD symptoms are in line with previous studies (e.g., Reiersen et al. 2008; Polderman et al. 2014).

Attention to detail, inattention, as well as hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms, are directly related to rumination. Burrows et al. (2017) suggested that negative self-referential processing and cognitive inflexibility might lead to rumination in individuals with ASD. Attention to detail might partly reflect circumscribed interests, and according to the theory by Burrows et al., this trait could arise as a result of difficulties in switching between mental processes (i.e., cognitive inflexibility), although this relationship has not been empirically examined to date. In addition, a recent meta-analysis has indicated that impaired set shifting component of executive function could be associated with rumination (Yang et al. 2017). Therefore, it is plausible that individuals with a higher level of attention to detail might continue to ruminate as a result of being unable to disengage from negative environmental and internal information.

One possible reason why inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms were directly related to rumination could be the poor academic achievement. A previous study has reported that ADHD symptoms and especially inattention in undergraduate students were related to lower high school and university grade point averages (GPA), withdrawal from classes, a lower frequency of taking notes, and a shorter time and less intensive study (Frazier et al. 2007; Advokat et al. 2011). In addition, it has been suggested that ADHD symptoms and especially hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms during young adulthood cause adverse driving outcomes such as tickets, accidents, and license suspensions and revocations (Fischer et al. 2007; Thompson et al. 2007). Frequent exposure to stressors is concurrently and prospectively associated with increased rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 1994; Moberly and Watkins 2008a; Michl et al. 2013). Moreover, according to the goal progress theory of rumination (Martin et al. 2004), stressors can keep a person’s goals unattained and lead to rumination about information related to the unattained goals. Based on this theory and previous findings, it is possible that ADHD symptoms might cause academic difficulties or adverse driving outcomes, and exposure to such stressors might result in prolonged rumination.

Bootstrap analyses showed that attention to detail, inattention, and hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms were indirectly associated with depression via rumination. Furthermore, a model that includes brooding and reflection subscales instead of RRS total scale score indicated that inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms, but not attention to detail intensified depression through brooding, but not through reflection. These findings indicate that depressive rumination and especially blooding which is assumed to be the maladaptive subcomponent of rumination mediates the associations of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms as well as attention to detail with depressive symptoms in non-clinical undergraduate students, although it is cautious that mediating role of brooding between attention to detail and depression was slightly weak and therefore not statistically significant.

It is plausible that interventions focusing on rumination would be effective in alleviating depression in young adults with high ASD and ADHD symptoms. Previous studies have reported that the practice of mindfulness meditation decreases rumination and depressive symptoms in depressed people (Ramel et al. 2004; Kingston et al. 2007; Geschwind et al. 2011). Moreover, the same positive effects were observed in high-functioning adults with ASD (Spek et al. 2013; Kiep et al. 2015). Interestingly, recent studies have suggested that mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, which is a combination of mindfulness and cognitive therapy, decreases inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms in ADHD adults (Gu et al. 2018; Hepark et al. in press). The results of this study suggest that such a reduction of symptoms might also result in decreased rumination. Therefore, it is possible that mindfulness meditation would be an effective treatment to decrease rumination directly or indirectly via the reductions of ADHD symptoms, leading to preventing depression in people with high autistic traits and symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity.

The present study has theoretical implications, as well as clinical ones described above. Many previous studies have examined possible causes of rumination, such as deficits in executive functions (Yang et al. 2017, for review), and familial and genetic origins (Nolen-Hoeksema and Watkins 2011, for review). The present findings, as well as previous findings based on non-clinical and clinical samples (Crane et al. 2013; Oddo et al. 2018; Keenan et al. in press), suggest that ASD and ADHD symptoms might be one of the risk factors for increasing rumination. More studies focusing on the relationship of ASD and ADHD symptoms at a subclinical level and the diagnosis of these disorders with rumination would contribute to identifying all the reasons why certain individuals suffer from prolonged rumination whereas others do not.

The present study had some limitations. Although this study adopted the two-factor model of AQ proposed by Hoekstra et al. (2008), this model does not describe factors assessing restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviors, which are a core symptom in ASD. Also, the two-factor model was confirmed with data from a nonclinical sample rather than an adult ASD sample (Hoekstra et al. 2008). Therefore, it is possible that the two-factor model does not accurately represent traits that are continuous with ASD. Indeed, Lau et al. (2013) conducted an exploratory factor analysis of AQ with a sample, one-third of which consisted of individuals diagnosed with ASD, and they extracted a different factor structure from the original two factor model of AQ. We adopted the two-factor model because it has the advantage of being more parsimonious than the other models and because it overlaps with the cardinal DSM-5 symptoms of ASD. However, it is suggested that future studies should identify the factor structure of the AQ that fits well with both the general population and adult ASD samples, and adopt that factor structure to investigate aspects of autistic traits that are related to interpersonal conflict, rumination, and depression.

Second, the internal consistency of attention to detail subscale in this study was low. Previous studies have also indicated that internal consistency of the attention to detail subscale was around .60 (Baron-Cohen et al. 2001; Wakabayashi et al. 2004; Hoekstra et al. 2008), although test-retest reliability of this subscale over 1–6 months was within the acceptable range (r = .71; Hoekstra et al. 2008). Many previous studies that conducted exploratory or confirmatory factor analyses have extracted a factor corresponding to attention to detail (Austin 2005; Hurst et al. 2007; Stewart and Austin 2009; Kloosterman et al. 2011; except for Lau et al. 2013), indicating that attention to detail is an important dimension of autistic traits. It is suggested that future studies should reconstruct the item composition of this subscale and improve its internal consistency to examine whether the attention to detail component of autistic traits is really related to rumination and depression.

Third, as described above, the present study is a cross-sectional study, and future studies should adopt a longitudinal design to identify causality. Fourth, results of structural equation modeling showed that social interaction and hyperactivity-impulsivity were directly associated with depression, which is suggestive of mediators other than rumination. It would be fruitful to examine mediators other than those that were assessed in this study. Finally, assessments were conducted only by using self-report measures, and it would be necessary to assess each variable with other methods such as structured interview. Future studies that are designed to overcome these limitations would further advance the theory, as well as the treatment of adults with high levels of ASD and ADHD symptoms, rumination, and depression.

Notes

The two-factor model proposed by Hoekstra et al. (2008) has the limitation that the model does not include factors assessing restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviors, which are a core symptom in ASD. Also, Hoekstra et al. (2008) conducted confirmatory factor analyses with data from a sample that consisted of university students and the general population but not an adult ASD sample. Therefore, it is possible that the two-factor model does not accurately represent the traits that are continuous with ASD. The present study adopted the two-factor model after taking the advantages of this model described above into consideration. We have discussed the limitations of the model in the Discussion section.

Although 22 items of the RRS was rated on a 4-point rating scale anchored between 0 and 3 in Oddo et al. (2018), these items were usually rated between 1 and 4. If a standard rating scale were adopted, mean RRS scores of the adult ADHD group in Oddo et al. (2018) would have been 54.01, indicating this group ruminates more frequently than the general population group (e.g., mean RRS scores of general population were 42.01 for women and 39.64 for men in the study by Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 1999; See also Table 1 described below).

Consistent with our notion, difficulties in social interaction was not significantly correlated with interpersonal conflict after controlling for hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms (pr = .05, p = .37)

References

Advokat, C., Lane, S. M., & Luo, C. (2011). College students with and without ADHD: Comparison of self-report of medication usage, study habits, and academic achievement. Journal of Attention Disorders, 15, 656–666.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Austin, E. J. (2005). Personality correlates of the broader autism phenotype as assessed by the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ). Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 451–460.

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., & Clubley, E. (2001). The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 5–17.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Burrows, C. A., Timpano, K. R., & Uddin, L. Q. (2017). Putative brain networks underlying repetitive negative thinking and comorbid internalizing problems in autism. Clinical Psychological Science, 5, 522–536.

Crane, L., Goddard, L., & Pring, L. (2013). Autobiographical memory in adults with autism spectrum disorder: The role of depressed mood, rumination, working memory and theory of mind. Autism, 17, 205–219.

Farley, M. A., McMahon, W. M., Fombonne, E., Jenson, W. R., Miller, J., Gardner, M., et al. (2009). Twenty-year outcome for individuals with autism and average or near-average cognitive abilities. Autism Research, 2, 109–118.

Fischer, M., Barkley, R. A., Smallish, L., & Fletcher, K. (2007). Hyperactive children as young adults. Driving abilities, safe driving behavior, and adverse driving outcomes. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 39, 94–105.

Frazier, T. W., Youngstrom, E. A., Glutting, J. J., & Watkins, M. W. (2007). ADHD and achievement: Meta-analysis of the child, adolescent, and adult literatures and a concomitant study with college students. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 40, 49–65.

Geschwind, N., Peeters, F., Drukker, M., van Os, J., & Wichers, M. (2011). Mindfulness training increases momentary positive emotions and reward experience in adults vulnerable to depression: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 618–628.

Gotham, K., Bishop, S. L., Brunwasser, S., & Lord, C. (2014). Rumination and perceived impairment associated with depressive symptoms in a verbal adolescent-adult ASD sample. Autism Research, 7, 381–391.

Gu, Y., Xu, G., & Zhu, Y. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for college students with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 22, 388–399.

Hasegawa, A. (2013). Translation and initial validation of the Japanese version of the Ruminative Responses Scale. Psychological Reports, 112, 716–726.

Hashimoto, T. (1997). Daigakusei ni okeru taijin stress event bunrui no kokoromi [categorization of interpersonal stress events among undergraduates]. Japanese Journal of Social Psychology, 13, 64–75 [in Japanese].

Hepark, S., Janssen, L., de Vries, A., Schoenberg, P. L. A., Donders, R., Kan, C. C., & Speckens, A. E. M. (in press). The efficacy of adapted MBCT on core symptoms and executive functioning in adults with ADHD: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of Attention Disorders. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715613587.

Hoekstra, R. A., Bartels, M., Verweij, C. J. H., & Boomsma, D. I. (2007). Heritability of autistic traits in the general population. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine, 161, 372–377.

Hoekstra, R. A., Bartels, M., Cath, D. C., & Boomsma, D. I. (2008). Factor structure, reliability and criterion validity of the Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ): A study in Dutch population and patient groups. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1555–1566.

Howlin, P., Goode, S., Hutton, J., & Rutter, M. (2004). Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 212–229.

Hurst, R. M., Mitchell, J. T., Kimbrel, N. A., Kwapil, T. K., & Nelson-Gray, R. O. (2007). Examination of the reliability and factor structure of the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) in a non-clinical sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1938–1949.

Kanai, C., Iwanami, A., Hashimoto, R., Ota, H., Tani, M., Yamada, T., & Kato, N. (2011). Clinical characterization of adults with Asperger’s syndrome assessed by self-report questionnaires based on depression, anxiety, and personality. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 1451–1458.

Keenan, E. G., Gotham, K., & Lerner, M. D. (in press). Hooked on a feeling: Repetitive cognition and internalizing symptomatology in relation to autism spectrum symptomatology. Autism. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317709603

Kessler, R. C., Adler, L., Ames, M., Demler, O., Faraone, S., Hiripi, E., et al. (2005). The World Health Organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): A short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychological Medicine, 35, 245–256.

Kessler, R. C., Adler, L., Barkley, R., Biederman, J., Conners, C. K., Demler, O., et al. (2006). The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 716–723.

Kiep, M., Spek, A. A., & Hoeben, L. (2015). Mindfulness-based therapy in adults with an autism spectrum disorder: Do treatment effects last? Mindfulness, 6, 637–644.

Kingston, T., Dooley, B., Bates, A., Lawlor, E., & Malone, K. (2007). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for residual depressive symptoms. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 80, 193–203.

Kloosterman, P. H., Keefer, K. V., Kelley, E. A., Summerfeldt, L. J., & Parker, J. D. A. (2011). Evaluation of the factor structure of the Autism-Spectrum Quotient. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 310–314.

Kojima, M., & Furukawa, T. (2003). Manual for the Beck depression inventory-II (Japanese translation). Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo: Nihon Bunka Kagakusha Co., Ltd.

Lau, W. Y. P., Kelly, A. B., & Peterson, C. C. (2013). Further evidence on the factorial structure of the autism spectrum quotient (AQ) for adults with and without a clinical diagnosis of autism. Journal of Autism Developmental Disorders, 43, 2807–2815.

Lever, A. G., & Geurts, H. M. (2016). Psychiatric co-occurring symptoms and disorders in young, middle-aged, and older adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 1916–1930.

Mannuzza, S., Castellanos, F. X., Roizen, E. R., Hutchison, J. A., Lashua, E. C., & Klein, R. G. (2011). Impact of the impairment criterion in the diagnosis of adult ADHD: 33-year follow-up study of boys with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 15, 122–129.

Martin, L. L., Shrira, I., & Startup, H. M. (2004). Rumination as a function of goal progress, stop rules, and cerebral lateralization. In C. Papageorgiou & A. Wells (Eds.), Depressive rumination: Nature, theory, and treatment (pp. 153–175). West Sussex: Wiley.

McKinney, A. A., Canu, W. H., & Schneider, H. G. (2013). Distinct ADHD symptom clusters differentially associated with personality traits. Journal of Attention Disorders, 17, 358–366.

Michl, L. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Shepherd, K., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2013). Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: Longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 339–352.

Moberly, N. J., & Watkins, E. R. (2008a). Ruminative self-focus, negative life events, and negative affect. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 1034+1039.

Moberly, N. J., & Watkins, E. R. (2008b). Ruminative self-focus and negative affect: An experience sampling study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 314–323.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 569–582.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 115–121.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Watkins, E. R. (2011). A heuristic for developing transdiagnostic models of psychopathology: Explaining multifinality and divergent trajectories. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 589–609.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Parker, L. E., & Larson, J. (1994). Ruminative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 92–104.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Larson, J., & Grayson, C. (1999). Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1061–1072.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 400–424.

Oddo, L. E., Knouse, L. E., Surman, C. B. H., & Safren, S. A. (2018). Investigating resilience to depression in adults with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 22, 497–505.

Polderman, T. J. C., Hoekstra, R. A., Posthuma, D., & Larsson, H. (2014). The co-occurrence of autistic and ADHD dimensions in adults. An etiological study in 17770 twins. Translational Psychiatry, 4, e435.

Ramel, W., Goldin, P. R., Carmona, P. E., & McQuaid, J. R. (2004). The effects of mindfulness meditation on cognitive processes and affect in patients with past depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28, 433–455.

Reiersen, A. M., Constantino, J. N., Grimmer, M., Martin, N. G., & Todd, R. D. (2008). Evidence for shared genetic influences on self-reported ADHD and autistic symptoms in young adult Australian twins. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 11, 579–585.

Rosbrook, A., & Whittingham, K. (2010). Autistic traits in the general population: What mediates the link with depressive and anxious symptomatology? Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 415–424.

Schoofs, H., Hermans, D., & Raes, F. (2010). Brooding and reflection as subtypes of rumination: Evidence from confirmatory factor analysis in nonclinical samples using the Dutch Ruminative Response Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32, 609–617.

Spek, A. A., van Ham, N. C., & Nyklíček, I. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy in adults with an autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34, 246–253.

Stewart, M. E., & Austin, E. J. (2009). The structure of the Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ): Evidence from a student sample in Scotland. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 224–228.

Takeda, T., Tsuji, Y., & Kurita, H. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the Adult Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Self-Report Scale (ASRS-J) and its short scale in accordance with DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 63, 59–66.

Theriault, S. W., & Holmberg, D. (2001). Impulsive, but violent? Are components of the attention deficit-hyperactivity syndrome associated with aggression in relationships? Violence Against Women, 7, 1464–1489.

Thompson, A. L., Molina, B. S. G., Pelham, W., & Gnagy, E. M. (2007). Risky driving in adolescents and young adults with childhood ADHD. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 745–759.

Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 247–259.

Uchida, M., Spencer, T. J., Faraone, S. V., & Biederman, J. (2018). Adult outcome of ADHD: An overview of results from the MGH longitudinal family studies of pediatrically and psychiatrically referred youth with and without ADHD of both sexes. Journal of Attention Disorders, 22, 523-534.

Vierikko, E., Pulkkinen, L., Kaprio, J., & Rose, R. J. (2004). Genetic and environmental influences on the relationship between aggression and hyperactivity-impulsivity as rated by teachers and parents. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 7, 261–274.

Wakabayashi, A., Tojo, Y., Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2004). Jihei-sho spectrum shisuu (AQ) nihongo-ban no hyoujunka: Koukinou rinsyou-gun to kenjou seijin ni yoru kentou [the autism-spectrum quotient (AQ) Japanese version: Evidence from high-functioning clinical group and normal adults]. The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 75, 78–84 [in Japanese].

Yang, Y., Cao, S., Shields, G. S., Teng, Z., & Liu, Y. (2017). The relationships between rumination and core executive functions: A meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 34, 37–50.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

Koji Horibe and Akira Hasegawa declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Horibe, K., Hasegawa, A. How Autistic Traits, Inattention and Hyperactivity-Impulsivity Symptoms Influence Depression in Nonclinical Undergraduate Students? Mediating Role of Depressive Rumination. Curr Psychol 39, 1543–1551 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9853-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9853-3