Abstract

The study of the fertility of immigrants has received much attention in recent years, particularly in societies with fertility rates below replacement levels. However, fertility in refugee populations remains understudied. Using rich register data on all female refugees of childbearing age (15–45 years) who arrived and settled in Norway between 2002 and 2015 (N = 23,527), we utilize the Norwegian settlement policy for refugees—which assigns all refugees coming to Norway to a municipality where they start their integration process—to study how fertility behavior in the years following settlement is related to the characteristics of the municipality to which refugee women are assigned. Importantly, we are able to control for individual-level characteristics used by the government agency at assignment, thus limiting the problem of selection on (un)observables. As explanatory variables, we focus on municipality unemployment rates, the share of non-Western immigrants already living in the municipality, and the total fertility rate in the municipality, and also control for the municipality’s age structure and childcare coverage. The study is thus of an exploratory nature. We measure these municipality characteristics the year before refugees settle and estimate their respective correlations with fertility (measured as the likelihood of having had at least one child in Norway) at the individual level for up to 8 years after settlement. We also explore heterogeneity by education and parity at settlement. We find no systematic associations between the share of non-Western immigrants in the municipality and refugees’ fertility; however, the municipality’s fertility rate is positively correlated with the likelihood of giving birth to a child in Norway, especially for women who are childless at arrival. The links between local unemployment rates and fertility are heterogeneous across education groups and parity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Due to data regulations and privacy concerns, we do not have access to data on sexual orientation or severe physical illnesses suffered by the women in our sample.

See, for instance, Saarela and Skirbekk (2019) on the fertility of the Karelian population forced to move to other regions of Finland in the 1940s.

Intention to treat (ITT) is a concept borrowed from experimental methods which refers to estimates that are based on the initial treatment assignment (i.e., the assigned municipality) and not on the treatment eventually received (i.e., the municipality where an individual actually lives after a certain number of years in Norway) (Angrist & Pischke, 2008). We report ITT estimates first and foremost because we are interested in the municipality of assignment, and because these are not biased by systematic selection in later internal migration. Since most refugees stay in the assigned municipality (Ordemann, 2017), the difference between ITT and other estimates such as ATE (average treatment effect) is minimized.

Note that Balbo et al. (2013) show that some macro-level studies also look at the role of contraceptive technologies or differences in welfare regimes in fertility dynamics which in our study should be homogeneous across Norwegian municipalities.

Spouses of persons who have been granted protection in Norway may also stay in Norway as long as they fulfil certain requirements (Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (UDI) 2020). Note that this group is not included in our analyses.

As other papers in the settlement literature mention, an additional concern is that unemployment rates of non-Western migrants may underestimate true unemployment if underemployment, self-employment, and discouragement are proportionally higher among migrants than among natives (Godøy, 2017). Thus, we can consider those rates as lower bound levels.

More precisely, 2G (two times the National Insurance scheme basic amount), which in 2019, equalled almost NOK 200,000.

This highlights that the assignment process is not completely random, and underscores the importance of using IMDi’s data on individual characteristics in our estimations.

Note that we have also estimated models with a count variable for the number of children a woman has had in Norway, and that the results show the same overall patterns.

If we were to follow them for more than eight years, our sample would be too small.

The only municipality variable in this study that is not available in StatBank is the TFR at municipality level, which is calculated by the authors based on population and birth data in Statistics Norway’s registers.

Discrepancies between the two data sets are discussed in Tønnessen and Andersen (2019).

Note, however, that for younger cohorts of native Norwegians, patterns of educational differences in (cohort) fertility have almost completely vanished (Jalovaara et al., 2019).

Furthermore, in separate estimations, we have added instead the share of votes for the Progress Party in the municipality at the national elections to capture anti-immigrant sentiment. The variable is statistically insignificant.

References

Adserà, A., & Ferrer, A. (2014) Immigrants and demography: marriage, divorce, and fertility. In Handbook on the Economics of International Migration, Volume 1, edited by B. R. Chiswick and P. W. Miller for the “Handbooks in Economics Series”, Kenneth J. Arrow and Michael D. Intriligator eds., Elsevier B.V.

Adserà, A., Ferrer, A. M., Sigle-Rushton, W., & Wilson, B. (2012). Fertility patterns of child migrants age at migration and ancestry in comparative perspective. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 643(1), 160–189.

Anderson, G. (2004). Childbearing after migration: Fertility patterns of foreign-born women in Sweden. International Migration Review, 38(2), 747–774.

Andersson, H. (2018) Ethnic enclaves, self-employment and the economic performance of refugees. Nationalekonomiska institutionen, Uppsala universitet. Retrieved from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-347043

Angrist, J., & Pischke, J.-S. (2008). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press.

Åslund, O., & Rooth, D.-O. (2007). Do when and where matter? initial labour market conditions and immigrant earnings*. The Economic Journal, 117(518), 422–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02024.x

Åslund, O., & Fredriksson, P. (2009). Peer effects in welfare dependence quasi-experimental evidence. Journal of Human Resources, 44(3), 798–825. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.44.3.798

Åslund, O., Östh, J., & Zenou, Y. (2010). How important is access to jobs? Old question—improved answer. Journal of Economic Geography, 10(3), 389–422. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbp040

Åslund, O., Edin, P.-A., Fredriksson, P., & Grönqvist, H. (2011). Peers, neighborhoods, and immigrant student achievement: Evidence from a placement policy. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3(2), 67–95. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.3.2.67

Balbo, N., Billari, F. C., & Mills, M. (2013). Fertility in advanced societies: A review of research. European Journal of Population/Revue Européenne de Démographie, 29(1), 1–38.

Beaman, L. A. (2012). Social networks and the dynamics of labour market outcomes: Evidence from refugees resettled in the U.S. The Review of Economic Studies, 79(1), 128–161. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdr017

Becker, G. (1981). A Treatise on the Family. Harvard University Press.

Bertrand, M., Luttmer, E. F. P., & Mullainathan, S. (2000). Network effects and welfare cultures. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 1019–1055.

Bevelander, P., & Lundh, C. (2007) Employment integration of refugees: The influence of local factors on refugee job opportunities in Sweden (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 958714). Social Science Research Network. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=958714

Billari, F. C., Philipov, D., & Testa, M. (2009). Attitudes, norms and perceived behavioural control: Explaining fertility intentions in Bulgaria. European Journal of Population, 25(4), 439–465.

Blau, F. D. (1992). The fertility of immigrant women: Evidence from high-fertility source countries. In J. B. George & R. B. Freeman (Eds.), Immigration and the Work Force: Economic Consequences for the United States and Source Areas (pp. 93–133). The University of Chicago Press.

Brewster, K. L. (1994). Neighborhood context and the transition to sexual activity among young black women. Demography, 31(4), 603–614.

Brochman, G., & Hagelund, A. (2011). Migrants in the Scandinavian Welfare State. The Emergence of a Social Policy Problem. Nordic Journal of Migration Research, 1, 13–24.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94(Suppl), S95–S120.

Dahlberg, M., Edmark, K., & Berg, H. (2012). Ethnic diversity and preferences for redistribution. Journal of Political Economy, 120(1), 41–76.

Damm, A. P. (2009). Ethnic enclaves and immigrant labor market outcomes: Quasi-experimental evidence. Journal of Labor Economics, 27(2), 281–314. https://doi.org/10.1086/599336

Damm, A. P. (2014). Neighborhood quality and labor market outcomes: Evidence from quasi-random neighborhood assignment of immigrants. Journal of Urban Economics, 79, 139–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2013.08.004

Del Bono, E., Weber, A., & Winter-Ebmer, R. (2012). Clash of career and family: fertility decisions after job displacement. Journal of the European Economic Association, 10(4), 659–683.

Directorate of integration and diversity - Integrerings- og mangfoldsdirektoratet (2020) Stans av introduksjonsprogrammet. https://www.imdi.no/introduksjonsprogram/regler-om-deltakelse-i-introduksjonsprogramet/stans-av-introduksjonsprogram/. Accessed Aug 2020.

Djuve, A. B., & Kavli, H. C. (2007) Integrering i Danmark, Sverige og Norge : Felles utfordringer - like løsninger? Nordisk ministerråd. Retrieved from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:norden:org:diva-1199

Dribe, M., Juárez, S. P., & Scalone, F. (2017). Is it who you are or where you live? Community effects on net fertility at the onset of fertility decline: A multilevel analysis using Swedish micro-census data. Population, Space and Place, 23(2), e1987.

Edin, P.-A., Fredriksson, P., & Åslund, O. (2003). Ethnic enclaves and the economic success of immigrants—Evidence from a natural experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 329–357. https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530360535225

Edin, P.-A., Fredriksson, P., & Åslund, O. (2004). Settlement policies and the economic success of immigrants. Journal of Population Economics, 17(1), 133–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-003-0143-4

Fasani, F., Frattini, T., & Minale, L. (2018) (The Struggle for) Refugee Integration into the Labour Market: Evidence from Europe (SSRN Scholarly Paper). Social Science Research Network.

Fernández, R., & Fogli, A. (2009). Culture: An empirical investigation of beliefs, work, and fertility. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 1(1), 146–177.

Godøy, A. (2017). Local labor markets and earnings of refugee immigrants. Empirical Economics, 52(1), 31–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-016-1067-7

Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., & Lappegård, T. (2015). The gender revolution: Theoretical framework for understanding new family-demographic behavior. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 207–239.

Goldstein, S., & Goldstein, A. (1983). Inter-relations between migration and fertility: Their significance for urbanisation in Malaysia. Habitat International, 8(1), 93–103.

Grönqvist, H., Niknami, S., & Robling, P. O. (2015) Childhood exposure to segregation and long-run criminal involvement - Evidence from the “Whole of Sweden” Strategy. SOFI Working Paper, 1/2015.

Hank, K. (2002). Regional social contexts and individual fertility decisions: A multilevel analysis of first and second births in western Germany. European Journal of Population, 18(3), 281–299.

Hill, L., & Johnson, H. (2004). Fertility changes among immigrants: Generations, neighborhoods, and personal characteristics. Social Science Quarterly, 85(3), 811–826.

Høydahl, E. (2017). Ny sentralitetsindeks for kommunene. Documents 2017/40, Statistics Norway.

Jalovaara, M., Neyer, G., Andersson, G., et al. (2019). Education, gender, and cohort fertility in the nordic countries. European Journal of Population, 35, 563–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-018-9492-2

Kahn, J. R. (1988). Immigrant selectivity and fertility adaptation in the United States. Social Forces, 67(1), 108–128.

Kraus, E., Sauer, L., & Wenzel, L. (2019). Together or apart? Spousal migration and reunification practices of recent refugees to Germany. Journal of Family Research, 31(3), 303–332.

Kravdal, Ø. (2016) Not so low fertility in Norway—A result of affluence, liberal values, gender-equality ideals, and the welfare state Low Fertility, Institutions, and their Policies. Springer, Cham, 13–47.

Kulu, H. (2011) Why do fertility levels vary between urban and rural areas? Regional Studies, 1–17.

Kulu, H., & Milewski, N. (2007). Family change and migration in the life course: An introduction. Demographic Research, 17, 567–590.

Kulu, H., & Vikat, A. (2007). Fertility differences by housing type: The effect of housing conditions or of selective moves? Demographic Research, 17(26), 775–802.

Kulu, H., & Boyle, P. J. (2009). High fertility in city suburbs: Compositional or contextual effects? European Journal of Population, 25(2), 157–174.

Kulu, H., & González-Ferrer, A. (2014). Family dynamics among immigrants and their descendants in Europe: Current research and opportunities. European Journal of Population, 30(4), 411–435.

Kulu, H., & Washbrook, E. (2014). Residential context, migration and fertility in a modern urban society. Advances in Life Course Research, 21, 168–182.

Kulu, H., Boyle, P., & Andersson, G. (2009). High suburban fertility: Evidence from Four Northern European Countries. Demographic Research, 21(31), 915–944.

Kulu, H., Milewski, N., Hannemann, T., & Mikolai, J. (2019). A decade of life-course research on fertility of immigrants and their descendants in Europe. Demographic Research, 40(46), 1345–1374.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010) “The unfolding story of the second demographic transition,” Population and Development Review, June, 36(2): 211–251.

Lovdata (2020) Introduksjonsloven (The Norwegian Introductory Act). https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2003-07-04-80. Accessed Aug 2020.

Manski, C. F. (1993). Identification of endogenous social effects: The reflection problem. The Review of Economic Studies, 60(3), 531–542.

Manski, C. F. (1995). Identification problems in social sciences. New York: Harvard University Press.

Milewski, N. (2007). First child of immigrant workers and their descendants in West Germany: Interrelation of events, disruption, or adaptation? Demographic Research, 17, 859–896.

Milewski, N. (2010). Fertility of immigrants. A two-generational approach in Germany. Springer.

Milewski, N., & Mussino, E. (2019). Editorial on the special issue “new aspects on migrant populations in Europe: Norms, attitudes and intentions in fertility and family planning.” Comparative Population Studies, 43, 371–398.

Montgomery, M. R., & Casterline, J. B. (1996) Social influence, social learning, and new models of fertility. In J. Casterline, R. Lee, & K. Foote (Eds.), Fertility in the United States: New patterns, new theories (pp. 87–99).

Mulder, C. (2006). Population and housing: A two-sided relationship. Demographic Research, 15(13), 401–412.

Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (UDI) (2020) Family immigration with a person who has protection (asylum) in Norway. https://www.udi.no/en/word-definitions/family-immigration-with-a-person-who-has-protection-asylum-in-norway/ Accessed August 2020.

Ordemann, Adrian Haugen, 2017: Monitor for sekundærflytting. Sekundærflytting blant personer med flyktningbakgrunn bosatt i Norge 2005–2014. Reports 2017/18, Statistics Norway

Philipov, D., Speder, Z., & Billari, F. C. (2006). Soon, later, or ever? The impact of anomie and social capital on fertility intentions in Bulgaria (2002) and Hungary (2001). Population Studies, 60(3), 289–308.

Ruis, A. (2019) Building a new life and (re)making a family. Young Syrian refugee women in the Netherlands navigating between family and career. Journal of Family Research 31(3), 287–302.

Saarela, J., & Skirbekk, V. (2019). Forced migration in childhood and subsequent fertility: The Karelian displaced population in Finland. Population, Space and Place, 25(6), e2223.

Schaller, J. (2016). Booms, busts, and fertility: Testing the becker model using gender-specific labor demand. Journal of Human Resources, 51(1), 1–29.

Statistics Norway (2019) Immigrants and Norwegian-Born to Immigrant parents. Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/en/innvbef.

Statistics Norway (2020a) Immigrants by reason for immigration. Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/en/innvgrunn, August 2020.

Statistics Norway (2020b) Persons with refugee background. Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/flyktninger

Sobotka, T., Skirbekk, V., & Philipov, D. (2011). Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. Population and Development Review, 37(2011), 267–306.

Stephen, E. H., & Bean, F. D. (1992). Assimilation, disruption and the fertility of Mexican–origin women in the United States. International Migration Review, 26(1), 67–88.

Tønnessen, M. (2019) Declined total fertility rate among immigrants and the role of newly arrived women in Norway. Forthcoming in European Journal of Population.

Tønnessen, M. and S. Andersen (2019) Bosettingskommune og integrering blant voksne flyktninger: Hvem bosettes hvor, og hva er sammenhengen mellom bosettingskommunens egenskaper og videre integreringsutfall?, Rapporter 2019/13, Statistics Norway.

Tønnessen, M., & Mussino, E. (2020). Fertility patterns of migrants from low-fertility countries in Norway. Demographic Research, 42, 859–874.

Tønnessen, M. and B. Wilson (2020) Visualising immigrant fertility: Profiles of childbearing and their implications for migration research. Journal of International Migration and Integration

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division (2019) International Migrant Stock 2019 (United Nations database, POP/DB/MIG/Stock/Rev.2019).

Valenta, M., & Bunar, N. (2010). State Assisted Integration: Refugee Integration Policies in Scandinavian Welfare States: The Swedish and Norwegian Experience. Journal of Refugee Studies, 23(4), 463–483. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feq028

Wilson, B., & Kuha, J. (2018). Residential segregation and the fertility of immigrants and their descendants. Population, Space and Place, 2018(24), e2098. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2098

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

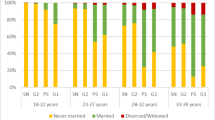

Appendix A: Descriptive statistics

Appendix B: Regression models

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andersen, S., Adserà, A. & Tønnessen, M. Municipality Characteristics and the Fertility of Refugees in Norway. Int. Migration & Integration 24 (Suppl 1), 165–208 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-021-00840-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-021-00840-2