Abstract

The practice in Leninist political systems of assigning local leaders concurrent seats on higher-level leadership bodies presents a puzzle. In China, for example, a subset of provincial leaders hold seats in the central Politburo, while some city-level leaders hold seats in provincial party standing committees (PPSCs). While some scholars view these concurrent appointments as a form of top-down control or co-optation, others see these arrangements as a reflection of local power and a channel for the assertion of local interests. In this paper, we attempt to adjudicate between these different views empirically by analyzing the patterns and consequences of concurrent appointments of city leaders to China’s PPSCs. We introduce a new typology that distinguishes between the political and economic functions of concurrent appointments to differentiate four possible intergovernmental dynamics of control, co-optation, compromise, and concession. Through analysis of an original dataset on PPSC appointments and case studies of three Chinese cities, we show that concurrent appointments in China’s provinces can function as a means of concession, compromise, or co-optation, but we find little evidence that concurrent appointments allow higher-level authorities to firmly control or economically exploit localities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Leninist political systems exemplify hierarchy. The Chinese party-state, for example, is built around a ladder of ascending authority, with party leadership bodies at each level of government that oversee subordinates and control the careers of lower-ranking officials (Landry 2008). Central and provincial leaders can impose dictates on the localities under them at will. The system may tolerate decentralization of administrative authority and “experimentation under hierarchy” (Zheng 2007; Heilmann 2008). But when all is said and done, firm political centralism ensures that it is higher-level decisions that count.

Notwithstanding this hierarchical template, however, Leninist authority structures are not always as clear-cut or rigid as they seem. One example is China’s practice of assigning the leaders of certain localities seats in higher-level party leadership bodies. At any given time, several of China’s provincial-level units enjoy representation on the central Politburo, the elite body of roughly two dozen party heavyweights that oversees key political and policy decisions.Footnote 1 At the subnational level, provincial party standing committees (PPSCs), the 12–13 member leadership bodies that run China’s regions, routinely allot 1, 2, or even 3 seats to the party chiefs of cities. The presence of lower-level leaders on party leadership bodies often involves a gaopei (“high match”) arrangement, whereby local leaders enjoy a higher party-political rank than they would have based on their local position.

These concurrent leadership appointments—and the tangled political hierarchies they create—are not unique to China. It also has been typical for certain local leaders to hold concurrent higher-level leadership positions in systems like the contemporary Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the historical USSR (Sheng 2009). The USSR Politburo, for instance, often included leaders of key cities and republics. As of 1984, the Politburo of the 26th Party Congress included leaders from Moscow, Leningrad, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, and Georgia (Lane 1985, pp. 166–168). In Vietnam, meanwhile, certain provincial party secretaries, particularly those from Ha Noi and Ho Chi Minh City, concurrently hold appointments in the central party-state (Malesky 2008).

Comparative scholarship on intergovernmental relations, much of which focuses on democratic settings, typically views the presence of local actors in higher-level political bodies as serving the interests of localities rather than higher-level authorities. When subnational units are represented in higher-level decision-making bodies, the thinking goes, they can assert their own political or economic interests. Tarrow (1978), Hutchcroft (2001), Falleti (2005), and Hooghe and Marks (2013), among others, view mechanisms of local representation such as the inclusion of territorial delegates in national legislatures or the participation of subnational actors in national-level bureaucratic processes as institutional factors that empower localities and enable local units to “utilize the center to their advantage” (Tarrow 1978, pp. 20–21). Empirical work from the USA and other democracies shows that localities whose representatives hold key positions in higher-level political bodies derive major benefits from such access (Carsey and Rundquist 1999; Berry and Fowler 2016).

In Leninist systems, however, the very notion that parochial interests are—or should be—represented in top leadership bodies is more suspect. With political power flowing from the top downward and formal accountability flowing upward, mechanisms that integrate local leaders into higher-level decision-making bodies may play very different roles. China scholars like Huang (1996) and Sheng (2009) see concurrent appointments as fully compatible with—indeed a natural outgrowth of—political hierarchy. Sheng (2009) argues that the presence of local leaders on higher-level bodies is a mode of political control over potentially problematic areas. By keeping local leaders close at hand, the thinking goes, higher-level leaders can keep localist ambitions at bay and ensure compliance with central policies. However, other China scholars, like Lam (2010) and Li (2016), see more ambiguity in the meaning of concurrent appointments. Rather than being a mode of top-down control, concurrent appointments might instead function as a softer form of co-optation, whereby higher-level authorities offer lower-level units expanded resources and political voice in exchange for their support of higher-level priorities, or even as a concession to powerful local actors. Seen this way, concurrent appointments could enable the representation of local interests in higher-level decision-making processes, and could reflect the strength rather than the weakness of local interests.

Different views of how and in whose interest concurrent leadership appointments work cut to fundamental questions about the political economy of Leninist systems. How these arrangements operate in practice has important implications for the way scholars conceptualize political control and interest representation in such polities. Can higher-level authorities subdue interest conflicts and ameliorate central-local conflicts by keeping key local leaders under closer watch? Is there institutional space even at high levels of Leninist party-states for local interests to assert themselves and promote parochial interests? Or perhaps concurrent appointments reflect a shifting intergovernmental bargain, whereby material benefits and “speaking rights” (fayan quan) are traded for political compliance?

After explaining why these questions are difficult to resolve at the theoretical level, this paper analyzes the patterns and outcomes of concurrent appointments empirically. We explore the determinants and outcomes of city leaders’ appointments to provincial leadership bodies, exploiting variation across provinces and over time in concurrent appointments. To guide our analysis, we develop a new typology that disentangles the political and economic dimensions of intergovernmental relations, distinguishing between policy autonomy and distributive outcomes. Drawing on city-level data and a dataset of the membership of PPSCs between 1996 and 2013 as well three city-level case studies, we assess how well concurrent appointment dynamics match the expectations associated with distinct logics of control, co-optation, compromise, and concession. We first analyze which types of cities enjoy PPSC representation and then explore how concurrent appointments affect subnational development and governance dynamics.

Our analysis challenges the idea that concurrent appointments serve simply to reinforce top-down control. Instead, we find that concurrent leadership appointments tend to bring either economic benefits or greater governance autonomy—or both—to the localities concerned. At the same time, our analysis suggests that the presence of city leaders on provincial leadership bodies has different consequences in different cases, and that the function of concurrent appointments differs across cities based on city characteristics. Overall, our findings suggest that China’s political hierarchy allows considerable flexibility, both in the determination of which cities’ leaders get selected for concurrent appointments and in the function of such representation. Even powerful Leninist regimes allow space for local interests to assert themselves in high-level politics and policymaking.

Local Actors in China’s Party Leadership Bodies

Past scholarship offers markedly different interpretations of the political function of concurrent leadership appointments in China. Scholars such as Huang (1996) and Sheng (2009, 2010) contend that concurrent appointment of local leaders to higher-level party leadership bodies enhances top-down control over localities rather than enabling bottom-up interest articulation. When it comes to provincial leaders in China’s Politburo, for example, Sheng (2009) argues that top-down appointment decisions reinforce upward political accountability, create “better alignment of the incentive structure” between local and national leaders, and improve the center’s capacity to monitor subordinates. Political leverage over local leaders helps ensure that localities comply with higher-level directives even when doing so may harm local interests. Huang’s (1996) study of the center’s crackdown on investment in China’s provinces finds that “concurrent centralists”—provincial leaders with Politburo seats—are more responsive to the center’s wishes and willing to impose costs on their jurisdictions. Huang and Sheng (2009) show that concurrent centralists achieve lower provincial inflation rates, which they interpret to mean that concurrent appointments make provinces more compliant with central austerity policies.

Yet, other scholars question whether concurrent appointments strengthen top-down control, noting that such arrangements may increase local actors’ influence over higher-level decisions. Discussing the appointment of certain provincial leaders to the central Politburo, Lam (2010) observes that “the meaning of provincial representation on these central institutions is far from immediately clear,” potentially signaling either “provincial clout” or “national integration.” Indeed, scholars such as Wang and Minzner (2015), Shi (2017), and Ma (2017) view concurrent appointments of the leaders of certain cities or bureaucratic units to provincial leadership bodies as a form of empowerment. As Shi (2017) notes, local leaders who are appointed to higher-level party standing committees “possess greater authority and power than other local officials at the same level in the administrative hierarchy, and are able to obtain favorable policies and policy support for their regions” (p. 83). Empirically, too, close political ties between lower and higher levels, and the representation of localities on higher-level leadership bodies, have been found to advance local interests. Li (1997) notes how Shanghai’s tight political relationship with Beijing cut both ways: while the municipality faced central policy demands and pressure to turn over fiscal revenues, it was also able to assert its interests in central decisions and capture economic resources and policy benefits. Ma (2017) finds that cities holding seats on PPSCs garner more mentions in provincial development plans and are privileged in the building of rail infrastructure. Bulman (2016) shows that counties with party secretaries who sit on prefectural party standing committees achieve faster growth than other counties.

Ultimately, the expected effects of concurrent appointments depend on our assumptions about decision-making processes and politicians’ incentives. Different models of China’s intergovernmental politics—a top-down principal-agent model and a bargaining model—yield contrasting expectations. Under the assumptions of a principal-agent model, concurrent appointments should strengthen top-down control. China’s nomenklatura system is meant to keep local leaders politically accountable to their superiors even as localities exercise a degree of administrative autonomy (Landry 2008). If the party’s chain of command is binding, then closer working ties with superiors should strengthen top-down monitoring and facilitate the sanctioning of subordinates in the event of non-compliance.

However, things are not so simple in practice. If local leaders are accountable to multiple principals, and if their career prospects do not depend solely on direct superiors’ support, they may be less compliant. During their postings, local leaders might become beholden to powerful local interests or find that successful completion of their official duties (needed for political promotion) requires them to cooperate closely with local bureaucratic or economic stakeholders. In such cases, politicians are more likely to defend the parochial interests of their own units and bargain aggressively with higher levels. The existence of rampant interest conflicts and bargaining within the party-state hierarchy is the essence of Lieberthal and Oksenberg’s (1988) “fragmented authoritarianism” model.

Concurrent appointments themselves may actually reinforce these bargaining dynamics, insofar as local leaders’ power, incentives, and relations with superiors are partly endogenous to concurrent appointments. By increasing the political rank and profile of local leaders, concurrent appointments have the potential to weaken top-down sanctioning capacity and upward accountability. The rise in rank that comes with concurrent appointments empowers local leaders—and, indirectly, their jurisdictions—by making them superior in bargaining power to erstwhile equals, and by enabling them to liaise with a broader range of political and bureaucratic actors. And concurrent appointments at the subnational level may create a multilevel game environment that adds to the multiple principals problem: although concurrently appointed local leaders remain subordinate to leaders at the next level up, who stand a half-rank above them, their appointment and removal is typically subject to the approval of party-state actors a full step higher as well. Concurrent appointments may thus dilute the authority and powers of sanction exercised by local leaders’ immediate superiors.

It is thus unclear on theoretical grounds whether concurrent appointments reinforce higher-level control or undermine it. Concurrent appointments could give local leaders more political autonomy from and power over entrenched interests in their jurisdictions, while also making local leaders more responsive to immediate superiors, but they could also give a more powerful political platform to actors who seek to champion local economic interests. Moreover, while either of these dynamics could dominate across the board, there could also be more varied effects on intergovernmental dynamics based on contextual factors. Ultimately, which type of intergovernmental dynamics prevails, or under what conditions different dynamics appear, is a question for empirical analysis.

Rethinking the Function of Concurrent Appointments

To help break this theoretical deadlock about the function of concurrent appointments, we differentiate between two dimensions of intergovernmental relations that do not necessarily move together in practice. One aspect of the relationship between higher-level and lower-level authorities concerns the degree of local policy autonomy that lower levels enjoy vis-à-vis their immediate superiors. At issue here is the degree to which lower-level units can pursue policies of their own devising, rather than being subordinated to higher-level plans and policies. If concurrent appointments tighten higher-level control, local units with concurrent appointments should display less policy activism of their own and adhere more closely to the priorities of higher-level authorities. On the other hand, if concurrent appointments enhance the autonomy of localities, there should be evidence that sub-units with concurrently appointed leaders are more likely than other units to devise policies that serve their own interests and challenge higher-level authority.

A different dimension of the relationship between higher- and lower-level actors concerns local economic benefits, or the distribution of economic costs and benefits between different government levels and territorial units. For reasons of career advancement, political patronage, or personal enrichment (Shih 2008; Landry et al. 2018), local leaders in China strive to attract resources to their jurisdictions and achieve strong economic performance. However, their ability to do so depends in part on their relationship with higher-level authorities. If, as Huang (1996) argues, concurrent leadership appointments help to ensure lower-level compliance with higher-level policies, the localities in question may have to pay a price in terms of development opportunities or economic resources. They may experience stricter economic regulation and reduced resource inflows, including lower levels of investment or fiscal transfers. They may also experience expanded outflows in the form of higher rates of taxation or fiscal revenue remittance. By contrast, if concurrent appointments advance local interests, or function as part of a bargain whereby political compliance is traded for material benefits, then localities whose leaders sit in higher-level decision-making bodies may capture more economic opportunities.

Taking these two dimensions into account, we construct a typology of four different intergovernmental dynamics that could arise from concurrent appointments, which we call control, co-optation, compromise, and concession. It is important to emphasize that, beyond simply being points along a spectrum from higher-level power to lower-level power, these are qualitatively different dynamics that have varying implications for the distribution of policymaking power and the allocation of costs and benefits (See Table 1).

Control, as we conceptualize it, is an intergovernmental relationship that serves the interests of higher-level authorities. The representation of local leaders on higher-level political bodies helps higher-level authorities more effectively monitor and enforce costly policies against localities. Such a dynamic is associated with less policy autonomy for localities, and is not likely to bring economic benefits.

Co-optation, in contrast, serves the interests of both higher-level authorities and localities. Localities sacrifice some of their policymaking autonomy, adhering closely to the dictates of higher-level authorities. At the same time, however, they derive economic benefits from a closer relationship with higher levels.

Compromise, as we define it, also addresses the interests of both higher-level authorities and localities, but in a different way. Localities with concurrently appointed leaders enjoy a greater degree of policymaking autonomy, allowing lower-level officials to tailor policies to local concerns. However, the localities do not enjoy increased economic support from above.

Finally, concession describes a scenario where concurrent appointments work to both the political and economic advantage of local interests. Under such an arrangement, localities retain a high degree of policymaking autonomy and also are able to advance their material interests by influencing higher-level policy decisions.

We expect that, for a given time and place, intergovernmental dynamics should approximate one of these four types. It seems likely, however, that different concurrent appointment dynamics may coexist in different places at the same time, or that dynamics may change over time in the same place. One possibility we explore below is that different types of localities are subject to different intergovernmental dynamics. China’s localities vary widely in terms of their economic importance and political significance, and local leaders may be concurrently appointed to higher-level leadership bodies for varying reasons and on different terms. This, in turn, could affect the development and governance outcomes associated with concurrent appointments.

City Leaders on Provincial Party Standing Committees

In the remainder of the paper, we examine appointments of prefectural-level leaders to China’s PPSCs to tests the empirical validity of the four dynamics discussed above. We focus on concurrent appointments to PPSCs for several reasons. First, provinces, and provincial-level institutions, are extremely important in China’s politics. Chinese provinces are comparable in population and economic terms to major countries and serve as key units of administration in China’s multilevel polity. Within provinces, PPSCs are the paramount decision-making bodies: they are the locus of political authority and oversee key personnel, policy, and allocative choices (Li 2007; Tan 2004; Bulman and Jaros 2018). While the internal workings of PPSCs remain opaque, several facts are clear. Such committees typically contain 12–13 members, including the provincial party secretary, the provincial governor, and other senior party and government officials. Whereas the top provincial leaders, the party secretary and governor, hold full provincial/ministerial-level rank, second-tier members of the PPSC have deputy-provincial rank. Members of PPSCs not only have a voice at the highest level of provincial politics; by virtue of their elite rank, they also have opportunities to interface directly with the party center. Indeed, all PPSC members’ appointments require Beijing’s approval (Zheng 2007; Landry 2008).

Besides PPSCs’ intrinsic importance, analysis at the subnational level allows us to take advantage of abundant data and empirical variation. Whereas studies of concurrent appointments of provincial leaders to the central Politburo are constrained by a small sample size (31 provincial-level units), we are able to collect data for roughly 300 prefectural-level units. And although the composition of PPSCs is largely standardized across provinces, there is marked variation in the extent to which local (prefectural-level) leaders are included, facilitating analysis of the consequences of concurrent appointments.

Information on the types of localities selected for concurrent appointments to higher-level leadership bodies may offer clues about the intended goals of such appointments, but there is little clear codification of the rules governing these appointments. This practice belongs more to the realm of “informal institutions” (Helmke and Levitsky 2004), or what are described in the Chinese context as “unwritten rules” (qian guize). According to reports from the Chinese media, the concurrent appointment of city-level leaders to PPSCs follows multiple logics in practice (Diyi caijing ribao 2014; Xin jing bao 2015). First, there is a subset of cities whose leaders appear to be concurrently appointed to PPSCs as a rule. This subset includes provincial capitals and deputy-provincial cities, which are generally the largest and most politically and economically important cities in China’s provinces.Footnote 2 Second, there are cities of economic or historical importance whose leaders appear to enjoy semi-institutionalized concurrent appointments, having gained PPSC seats and held onto them across multiple leadership transitions. Third, there is a subset of cities with more sporadic and unpredictable concurrent leadership appointments.

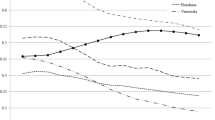

Our own data on PPSC lineups, drawing on a dataset originally constructed by Bulman and Jaros (2018), confirm this breakdown of “represented” cities into distinct tiers. Across the entire sample from 1996 to 2013, which includes data for all provincial-level units excluding China’s four centrally governed municipalities (Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Chongqing), 696 prefecture-years have a prefecture party secretary represented on the PPSC, 11.5% of the sample. Four hundred thirty-seven of these representation years belong to provincial capital cities, which typically hold seats on the PPSC. A further 85 representation years belong to non-capital deputy-provincial cities, namely Xiamen, Shenzhen, Dalian, Qingdao, and Ningbo. These cities already enjoy expanded formal economic and fiscal powers, and PPSC representation may thus have different effects for them. This leaves 174 prefecture-years with semi-institutionalized or sporadic concurrent appointments, or 3.3% of all non-capitals and non-deputy-provincial city observations. While representation of such cities is fairly rare, it has become more common over time, though this increase is not monotonic (see Fig. 1).

Although only 3.3% of non-capitals and non-deputy-provincial city-years have concurrently appointed leaders, a much larger sample of cities—44 (14.5%)—have concurrently appointed leaders for at least 1 year (see Table 4 in the appendix for a list of these cities). Six of these are represented for 10 or more years (more than half of the years in the sample). These six—Yanbian, Sanya, Suzhou, Yan’an, Ganzhou, and Luoyang—form a disparate group, including one of China’s richest cities (Suzhou), a geopolitically important autonomous prefecture that shares a border with North Korea (Yanbian), and two cities that played important historic roles as CCP base areas (Yan’an and Ganzhou).

The makeup of this subset suggests that cities’ economic and/or political importance influences selection for concurrent appointments; logit regressions of PPSC concurrent appointments on a set of potential explanatory factors in the statistical appendix confirm this expectation (see Table 5). Excluding capitals and deputy-provincial cities, which are always represented, levels of GDP, FDI, and revenue in a city are associated with a greater likelihood of representation, as is historical importance as key revolutionary base areas, which we proxy with “red tourism” status.Footnote 3 These results underscore the fact that there are multiple logics of representation. Provincial capitals and deputy-provincial cities enjoy regularized PPSC representation. Cities of economic importance, such as Suzhou, as well as historically and politically important “red cities,” like Yan’an, enjoy quasi-institutionalized representation. Other cities enjoy more sporadic and unpredictable PPSC representation.

By themselves, the characteristics of localities represented on PPSCs do not clarify the political functions served by concurrent leadership appointments. Regular representation in PPSCs of politically important and economically important cities, as well as the more sporadic representation of other cities, could be compatible with the distinct logics of control, co-optation, compromise, or concession. However, the fact that various classes of cities are selected for concurrent appointments underscores the possibility that there are different logics and consequences of PPSC representation for different cities.

Political and Economic Outcomes of Concurrent Appointments

We next turn to a quantitative assessment of the relationship between concurrent appointments and city-level outcomes. Are concurrent appointments associated with enhanced or reduced policy autonomy for the localities concerned? Are they associated with more or fewer economic benefits? The partially endogenous nature of concurrent appointments makes precise estimates of their causal effects difficult. Still, we can assess whether, or in which instances, the outcomes of concurrent appointments match the expectations of control, co-optation, compromise, or concession.

While concurrent appointments are identifiable using our dataset of PPSC membership, measuring city-level policymaking autonomy and distributive outcomes presents challenges. In assessing the level of policymaking autonomy cities enjoy vis-à-vis provincial authorities, our theoretical concern is whether cities merely implement provincial-level programs and policies or whether they undertake major policy initiatives of their own. Given the difficulty of directly gauging local policy activism of this sort, we use an indirect measure. Following an approach similar to Malesky’s (2008) analysis of regional policymaking autonomy in Vietnam, we use the frequency of national media coverage on reform-related topics in a given locality as a proxy for local policy activism. Specifically, we search online People’s Daily (renmin ribao) archives for articles that include the combination of a city’s name and one or more of four terms related to local reforms and experimentation: reform (gaige), innovation (chuangxin), pilot experiment (shidian), and model (shifan). This data collection yields city-year information on the number of article hits, comparable across cities over time, which we use as our policy autonomy proxy.

There are two key reasons why the degree of national-level media coverage related to reforms is a credible measure of local policy activism. First, reform-related coverage suggests that a city has a dynamic policymaking environment. Regardless of whether a city pioneers reforms on its own or is tapped from above to pilot new policies, policy innovation requires delegating discretion to front-line officials. Second, because the relevant media organs are not under the control of the localities themselves, national coverage attests to the external “newsworthiness” of developments occurring in a given city. Besides capturing instances where cities are mentioned in connection with reforms and policy experimentation, including reform-related search terms also helps to avoid excessive mismeasurement due to news stories about topics unrelated to public policies (e.g., natural disasters or corruption).

Of course, this measure is imperfect and picks up noise as well as signal (i.e., some identified news stories have little relation to policy autonomy or to the city in question). To ensure that the measure is capturing what we expect it to, we conduct a data validation exercise involving in-depth content analysis of a random sub-sample of identified articles. This exercise, which is detailed in the appendix, finds that around one-third of sampled articles very clearly report on local innovations and policy experiments; 8% are pure noise, with no substantive relation to the city in question; and the remainder are more ambiguous in their discussion of local policies but at least somewhat consistent with a policy autonomy interpretation. There is thus considerable measurement error, but because we only use this proxy as a dependent variable in our analyses, this error should not bias results, though it will tend to inflate standard errors and reduce the power of the regressions.Footnote 4

To assess the relationship between concurrent appointments and local economic outcomes, we test whether cities with concurrently appointed leaders exhibit systemically different local economic growth rates and fiscal balances. First, we examine whether localities’ rates of GDP and fixed-asset investment (FAI) growth systematically vary when local leaders have concurrent appointments. Investment and GDP growth in China are highly influenced by government behavior, so these growth rates help identify whether or not higher-level policies support the economic development of localities. In addition to growth measures, we also examine fiscal outcomes, including revenue and expenditure shares of GDP as well as localities’ fiscal gaps (i.e., the gap between expenditure and revenue shares of GDP). Increased revenue shares of GDP reflect greater success in fiscal extraction.Footnote 5 If this is matched by rising local expenditures, localities can be said to benefit. However, if higher revenue shares are not matched by rising expenditure (fiscal gaps decline), this may indicate greater upward revenue transfers at a cost to localities. Fiscal balances thus reflect a different kind of economic outcome that may or may not parallel FAI and GDP growth trends.

To test the relationship between concurrent appointments and local policy autonomy and economic outcomes, we regress these variables of interest on a dummy variable for city-years with concurrent appointments, controlling for income levels (logged per capita GDP), size (population), economic structure (primary and tertiary shares of GDP), and economic openness (FDI). To control for time-invariant differences across localities, our main analysis includes prefecture-level fixed effects. This requires us to exclude capital cities and deputy-provincial cities from the analysis.Footnote 6 Robustness checks in the appendix include provincial fixed effects and cluster standard errors at the prefectural level, thus allowing us to control for capital and deputy-provincial status as well as autonomous cities, “red” cities, and border cities (as defined in the previous section). All regressions include year fixed effects. The appendix includes summary statistics and a discussion of data collection, data assumptions, and missing data.

Our baseline regression results appear in Table 2. With regard to policy autonomy, we find that when cities have concurrently appointed leaders, they are significantly more likely to be mentioned in central news stories related to reform, which indicates greater local policy activism. When it comes to economic outcomes, cities display significantly faster GDP growth when they have concurrently appointed leaders. Fixed-asset investment growth is also faster, though not significantly so. And when cities have concurrently appointed leaders, they display greater revenue shares of GDP that are largely matched by greater expenditure shares, resulting in no significant fiscal gap. These results thus suggest that concurrent leadership appointments are associated with greater policy autonomy and enhanced economic benefits for cities, most closely matching a concession interpretation.

The above outcomes are based on an aggregated analysis, but, as noted earlier, concurrent appointments might have different consequences for different types of cities. To explore this possibility, we repeat the regression analysis using different subsets of relevant cities. Figure 2 below presents coefficient plots with 95% confidence intervals from regressions on four city-type sub-samples: the full sample, a sample of “rich” cities (defined here as those with GDP above the 75th percentile distribution in any given year), a sample of all “red” cities, and a sample of non-rich, non-red cities. (See Tables 8, 9, and 10 for full results.) To make the results more comparable, we use standardized z-scores rather than original values and present the results visually. When limiting the regressions to city-type sub-samples, the coefficient on the concurrent appointment dummy variable represents the difference in outcomes between represented cities and non-represented cities of the same type, rather than against all non-represented cities.Footnote 7

Coefficient plot of concurrent appointment effects across city types. Each bar in the chart represents a 95% confidence interval for the concurrent appointment dummy variable in a regression of the outcome variables listed in the column on the concurrent appointment dummy and the set of controls used in the regressions in Table 2. Each bar represents a separate regression. Six different regressions are repeated across three samples: the full sample, “red” cities, and rich cities (above 75th percentile GDP in a given year)

Results for the full sample, which echo the findings reported above in Table 2, are consistent with a concession interpretation, showing higher news frequency and better economic outcomes for cities with concurrent appointments. Interestingly, however, we find that concurrent appointments are associated with different outcomes for different types of cities. For the subset of rich cities, results largely match the aggregate results, but with larger and more statistically significant coefficients on the distributive outcomes. Here, concurrent appointments are associated with higher relative news frequency, higher growth and investment, and a combination of higher revenue and higher expenditure. This matches a concession interpretation. By contrast, outcomes for red cities more closely fit a compromise interpretation. Red cities with concurrent appointments experience much higher news frequency than red cities without concurrent appointments, suggesting higher policy autonomy. In terms of distributive outcomes, however, red cities exhibit no changes in GDP growth and slower FAI growth, with no clear significant changes in fiscal behavior. Finally, for the set of cities that are neither rich nor red, concurrent appointments show no clear relationship to the political and economic outcomes of interest. This implies either that concurrent appointments have no effect or, more likely, that they have disparate effects across these cities, perhaps determined by other contextual factors.

Two main conclusions stand out from this regression analysis. First, contrary to the idea that concurrent appointments are a mode of top-down control that imposes costs on cities, concurrent appointments are not associated with reduced policy autonomy or major economic costs. Instead, concurrent appointments are often associated with more reform-related news coverage and greater local economic benefits for localities, providing qualified support for the logics of concession, compromise, or co-optation.

Second, concurrent appointments have different consequences for different classes of cities. This suggests that concurrent appointments follow different political logics depending on local context, and that the effects of concurrent appointments may depend on the reasons why cities gained PPSC representation in the first place. Rich cities have many economic resources at their disposal and, given their wealth and importance as economic hubs, have some bargaining power with central and provincial governments even in the absence of concurrent appointments. These underlying economic and political strengths may make it easier for concurrently appointed city leaders to use their PPSC perch to advocate for local interests. Red cities, by contrast, lack strong local resource bases or strategic economic importance. As hallowed historical grounds, however, they enjoy special attention from China’s central party-state.Footnote 8 To the extent that such cities’ concurrent appointments come as a gift of empowerment from Beijing, such cities may have more political scope to undertake policies independent of their provincial superiors. As poor localities, however, such cities still need provincial support for their economic development, and this may be harder to come by if they are perceived as insubordinate. For other cities, which have neither special economic influence nor special central-level political support, concurrent appointments may be driven more by provincial-level policy agendas. Depending on what these agendas are, concurrent appointments might either work in favor of cities’ interests or against them.

Of course, while the above analysis shows compelling correlations, it does not provide conclusive evidence of the causal effects of concurrent appointments. Including city fixed effects and a battery of controls helps us control for several confounding factors. However, we cannot fully rule out the possibility of endogeneity: it is possible that cities expected to have greater economic vitality or policy experiments are assigned leaders with concurrent appointments, and not that concurrent appointments lead to these outcomes. Additionally, it is possible that concurrent appointments are typically granted to highly motivated or highly capable leaders, and that observed outcomes are based on these leader characteristics rather than institutional arrangements. To help clarify the causal sequences and causal logics at play, the next section uses process-tracing of concurrent appointment outcomes in different Chinese cities. Additionally, the online appendix explores the question of individual characteristics versus institutional arrangements in greater depth, providing preliminary evidence for an institutional interpretation based on observed leader characteristics and the city-level outcomes of different leaders prior to their concurrent PPSC appointments.

Different Models of Concurrent Appointment: Zhuhai, Ganzhou, and Xiangyang

While the analysis in the previous section suggests that concurrent appointments often benefit localities in terms of resource distribution and/or policymaking autonomy, it points to different concurrent appointment dynamics for different types of cities. To further clarify how concurrent appointments affect political and economic outcomes for different classes of cities and to begin shedding light on the causal mechanisms at work, this section examines the cases of Zhuhai (Guangdong), Ganzhou (Jiangxi), and Xiangyang (Hubei), drawing on a combination of Chinese media reports, secondary literature, and evidence from interviews.

The specific cases of Zhuhai, Ganzhou, and Xiangyang are selected for two main reasons. First, they represent different classes of cities: Zhuhai is a relatively wealthy coastal city (a rich city), Ganzhou is a former revolutionary base area (a red city), and Xiangyang, a minor inland industrial center, is neither. Second, these cities exhibit variation over time in concurrent PPSC appointments, enabling before-and-after comparisons. These cases provide qualitative evidence of both the circumstances and effects of concurrent appointments. They also illustrate the distinct dynamics of concession, compromise, and co-optation, as seen in Fig. 3, which compares measures of local autonomy and economic outcomes in the three cities during years with and without concurrent appointments.

Concurrent appointment effects in Zhuhai, Xiangyang, and Ganzhou. These values are calculated using data for the period 1996–2013. Relative news frequency refers to the provincial share of People’s Daily stories with a combination of city name and terms related to reform and policy experimentation; the GDP growth provincial differential is calculated on an annual basis as the difference between city-level GDP growth and average GDP growth for all cities in the province; the fiscal gap provincial differential is calculated on an annual basis as the difference between city-level fiscal gap (expenditure share of GDP minus revenue share of GDP) and the average fiscal gap for all cities in the province

Concurrent Appointment as Concession: Zhuhai

The case of Zhuhai city in Guangdong province approximates the idea of concurrent appointments as concession, whereby the leaders of localities with particular clout or importance gain PPSC seats and use this perch to promote local interests. Since the early 1990s, two Zhuhai leaders have concurrently served on Guangdong’s PPSC: Liang Guangda, between 1993 and 1998, and Li Jia, from 2012 until 2016, when he was removed from his post on corruption grounds. Although the leadership tenures of Liang and Li differed in some respects, both periods saw Zhuhai capture local economic benefits and launch high-profile policy initiatives that reflected some degree of autonomy. As Fig. 3 shows, during the terms of these leaders, Zhuhai achieved faster growth and a higher media profile.

Though small in population terms and outshined by leading Guangdong cities like Guangzhou and Shenzhen, Zhuhai has had outsize economic and geographic importance during the reform era. Sitting at the southwest corner of the Pearl River Delta (PRD), opposite Hong Kong and Shenzhen and directly bordering Macao, Zhuhai hosted one of China’s original four special economic zones (SEZs) and has served as the PRD’s western gateway (Sheng and Tang 2013). Given Zhuhai’s strategic location and economic role, it is not surprising that the city has enjoyed PPSC representation more than once.

When Liang Guangda became Zhuhai’s party chief in 1993, he had already developed a reputation as a locally oriented politician and economic booster, having reportedly declined opportunities to enter the provincial government (Lam 1999, p. 278). Between the mid 1980s and the early 1990s, Liang had served in Zhuhai, holding the post of deputy party secretary and mayor. In the same year that Liang became Zhuhai’s party chief, he also joined Guangdong’s PPSC. During the mid-1990s, Liang showed that he was unafraid to pursue developmental mega-projects even when provincial support was lacking. Liang promoted construction of a new Zhuhai-Guangzhou rail line in hopes that such a link would stimulate local economic growth. After being stonewalled by top provincial leaders in 1994, Liang made a political end run around them, seeking central support for the project (Xu and Yeh 2013). This brought resentment from Liang’s immediate superiors. As Xu and Yeh (2013) explain, “following central approval, Guangdong had to give its consent, but made it clear that the province would not invest in the railway because highways, rather than railways, were seen as the priority for provincial investment” (p. 140). Although Zhuhai’s rail project gained temporary momentum during Liang’s tenure, progress halted in 1998 after Liang left his leadership post. Liang’s gambit failed in the end, but Zhuhai’s defiance of provincial authority shows the difficulty of controlling cities with high-ranking leaders at the helm.

Over the following decade, Zhuhai’s economic position in Guangdong weakened. The city’s share of Guangdong’s provincial economic output fell from 3.1% in 1999 to 2.6% in 2012. This relative economic decline was not reversed until 2012, when another local leader gained a concurrent PPSC seat, and Zhuhai’s share of Guangdong’s GDP again began to climb (CDO; authors’ calculations). That year, Li Jia, who had risen through the ranks in another Guangdong locality, was installed as Zhuhai party secretary and also obtained a concurrent PPSC seat. As in the 1990s, having a leader with PPSC rank boosted Zhuhai’s policy activism and economic development.

While Zhuhai’s fading fortunes had begun to revive in 2009, when the city’s Hengqin island was granted enhanced economic and administrative powers as a state-level “New Area” (Ngo et al. 2017), a clearer inflection point came in 2012. During Li Jia’s tenure, Zhuhai again assumed a high-profile economic and policy role, positioning itself as a key engine of China’s “maritime economy.” In June 2013, Zhuhai announced that the Ferretti Group, one of the world’s largest yacht-making conglomerates, would spend three billion yuan to establish a new Asia headquarters in the city (Zhuhai tequ bao 2013). During the following 2 years, Li engaged with entrepreneurs, central government officials, and provincial policymakers, highlighting Zhuhai’s role in China’s maritime economy development and “Made in China 2025” strategies (Zhuhai tequ bao 2014; Zhongguo haiyang bao 2014; Zhuhai tequ bao 2015). This local boosterism paid dividends. In late 2015, Zhuhai, along with Guangzhou and Shenzhen, won permission from the central government to establish one of China’s pilot Free Trade Zones (FTZs) (Nanfang ribao 2015). Like the SEZ status granted three decades earlier, the FTZ designation was a major political achievement for a small city and promised big economic benefits. As Ngo et al. (2017) note, this arrangement—like the Hengqin New Area policy and Zhuhai’s historic SEZ status—further empowered Zhuhai’s already influential leaders, “allowing local state actors to manipulate multiscalar politics to their own advantage” (p. 70).

In sum, the case of Zhuhai illustrates how PPSC representation for wealthy cities can function as a concession, further strengthening localities in both economic and political terms. The tenures of Liang Guangda and Li Jia saw Zhuhai engage in bold efforts to promote local development. The city managed to raise its national profile and capture major economic benefits during these years, sometimes to the chagrin of a provincial government with other priorities. These periods contrast with the relative decline Zhuhai experienced in economic terms and in its public profile during the 2000s, when the city lacked a PPSC seat.

Concurrent Appointment as Compromise: Ganzhou

If the case of Zhuhai illustrates concession, the case of Ganzhou resembles what we call compromise, whereby concurrent appointments enhance local autonomy but do not yield clear economic benefits. Until 2002, Ganzhou lacked representation in Jiangxi’s PPSC. After 2003, however, Ganzhou’s leaders—first Pan Yiyang (2003–2010) and then Shi Wenqing (2011–2015)—held PPSC seats. Under both Pan and Shi, Ganzhou launched major policy initiatives to put a historically important region back on the map. However, greater local autonomy complicated relations with provincial authorities, limiting economic benefits.

Ganzhou is a mountainous prefectural-level city in southern Jiangxi. Due to its rugged topography and distinctive Hakka sub-culture, Ganzhou has never been tightly integrated with the wealthier northern half of Jiangxi. The region is Jiangxi’s largest in both geographic and population terms, and has historical significance as the location of the Jiangxi Soviet, a key revolutionary base area (Looney 2012, pp. 286–87). Despite its Communist legacy, Ganzhou remained predominantly rural and underdeveloped as it entered the twenty-first century.

During the early 2000s, Ganzhou’s economic development strategy took cues from the outward-oriented, industry-first development approach of Jiangxi’s provincial party secretary Meng Jianzhu, who had arrived in 2001. When Ganzhou was tasked by the province with building a new Ganzhou-Dingnan Expressway to link Jiangxi with Guangdong, for example, the municipal leadership gave high priority to this task (Jingji ribao 2002). More broadly, the city leadership emphasized building up its urban-industrial economy. An early 2003 newspaper article by Ganzhou’s mayor listed industry growth as the region’s top priority (Zhongguo xinxibao 2003).

If Ganzhou followed provincial development priorities between 2001 and 2003, the region’s development strategy changed sharply after Pan Yiyang became top leader. A Guangdong native, Pan had served in Jiangxi’s provincial establishment for just under 2 years when he was appointed as Ganzhou’s leader. Under Pan, Ganzhou reoriented its development approach to become a national frontrunner in “Socialist New Countryside Construction.” As detailed by Looney (2012, 2015), this initiative was identified with Pan himself, who already had a reputation as a rural development advocate. Pan spearheaded a large-scale campaign to rebuild rural settlements and restructure rural governance, drawing attention from national-level leaders and media in the process. This rural development campaign differed in tone from the pro-urban, pro-industrial strategy of the provincial leadership. While Pan did not necessarily defy provincial leaders, his initiative in some ways upstaged them (Jaros 2019).

Pan Yiyang’s successor, Shi Wenqing, also used his high political status to promote the visibility of Ganzhou. Shi became Ganzhou’s party secretary in late 2010, and took a seat on Jiangxi’s PPSC in early 2011. Like Pan, Shi lacked deep roots in Jiangxi, having served in the province for 2 years. After his arrival in Ganzhou, Shi launched a publicity blitz to highlight rural poverty in Ganzhou, and appealed for greater central funding to support development in the former Jiangxi Soviet area (Ibid.). Shi’s public appeals and personal outreach to China’s national leadership mobilized new support from the center. The 2012 Central Policy Document No. 21, which called for “revival and development” of the old Jiangxi Soviet and other base areas, promised new forms of aid to Ganzhou, including special tax policies, large-scale investment projects, and new state-level development zones (Renmin ribao 2014a; 2014b). According to a local journalist familiar with the origins of this initiative, the provincial level played at most a secondary role in lobbying for these special policies for Ganzhou (Interview NC011501b 2015; Jaros 2019).

In short, the case of Ganzhou reflects the dynamic we call compromise. Ganzhou’s experience shows the capacity of sub-provincial leaders to leverage their high status as PPSC members and promote locally oriented policy initiatives. After 2003, Ganzhou displayed a high degree of policymaking activism under concurrently appointed leaders Pan and Shi. Despite locally driven policy initiatives that attracted national attention, however, Ganzhou did not achieve above-average economic performance as compared with Jiangxi more broadly (see Fig. 3). This may be because local activism complicated relations between Ganzhou and provincial leaders, limiting the amount of support from the provincial level.

Concurrent Appointment as Co-optation: Xiangyang

In contrast with the experiences of Zhuhai and Ganzhou, the case of Xiangyang in Hubei province illustrates what we call co-optation, whereby a represented locality gains material benefits but is expected to follow higher-level priorities. For much of the period we examine, Xiangyang lacked PPSC representation. After 2011, however, the city’s fortunes changed. A provincial-level strategy aimed at grooming Xiangyang as one of Hubei’s two economic “sub-centers” brought new attention to the city. Xiangyang’s top leaders henceforth had PPSC appointments, and the city enjoyed growing economic support.

Xiangyang, called Xiangfan prior to 2011, is a medium-sized industrial city in northwest Hubei. During the Maoist period and early reform era, Xiangyang was a moderately important state-owned industry base, but the city’s livelihood declined after the 1990s amid liberalization. In recent decades, Xiangyang has lagged increasingly far behind Wuhan, the provincial capital, in population and economic size. Wuhan accounts for nearly a third of total provincial economic output, while the combined output of Hubei’s next two largest cities, Yichang and Xiangyang, is just over a fifth of provincial GDP (CDO; authors’ calculations). This regional imbalance within Hubei became a growing concern for policymakers after the mid-2000s, prompting new development approaches.

After 2003, Hubei pursued a “One Main Center, Two Secondary Centers” regional development strategy (21 shiji jingji baodao 2012). While promoting economic upgrading in Wuhan, the strategy also named Yichang and Xiangyang as growth poles for the less-developed western part of the province. Despite the rollout of the “One Main, Two Secondary” strategy, however, Wuhan’s economic dominance further increased during the 2000s. Redoubling efforts at regional coordination, Hubei’s 2011 government work report called for “grasping tightly research and formulation of the ‘One Main, Two Secondary’ policy, accelerating economic development policy measures, and giving play to Wuhan, Xiangyang, and Yichang’s core growth pole function” (Ibid.).

In addition to policy measures to stimulate growth in Xiangyang and Yichang, Hubei also used political mechanisms. After 2011, Hubei began allotting PPSC seats to the leaders of Xiangyang and Yichang (21 shiji jingji baodao 2013). In the case of Xiangyang, three successive city party secretaries held PPSC seats—Fan Ruiping (2011–2013), Wang Junzheng (2013–2016), and Ren Zhenhe (2016–2017). The decision to assign PPSC members to lead Hubei’s secondary cities from 2011 on reflected the province’s effort to “deepen” its support for the economic development of Xiangyang and Yichang. Assigning PPSC members to city-level posts was viewed as “an extremely important policy”—a kind of political capital at its most literal—that would complement other preferential policies for the city such as expanded project approval powers, fiscal benefits, and expanded land powers. As an official media report from 2017 noted, “under the political system of our country, this [appointment of city-level leaders to PPSC seats] implies that both cities will have the opportunity to garner more support, and this will therefore influence each city’s economic development, urban scale, and external linkages” (Hubei ribao 2017).

While it promised local economic benefits, however, Hubei’s decision to grant PPSC representation to city leaders was closely linked with a provincial-level development strategy. According to one report, the idea of providing Xiangyang and Yichang with PPSC seats had originated in 2007 with the Deputy Director of Hubei’s Provincial Academy of Social Sciences, Qin Zunwen. As Qin explained, “the administrative approach of having deputy provincial-level officials take responsibility for leadership of sub-center cities would not only make for more convenient coordination of relations with provincial departments, but would also facilitate cooperation with neighboring cities…” (21 shiji jingji baodao 2013). That is, concurrent appointment of Xiangyang’s and Yichang’s leaders was intended both to bolster the cities economically and to harmonize their development with that of other localities.

The representation of Xiangyang on Hubei’s PPSC thus illustrates a dynamic of co-optation, whereby economic benefits are exchanged for close local adherence to provincial priorities. Indeed, this interpretation is borne out by patterns of economic development and media coverage in Xiangyang. Although the city’s share of Hubei’s GDP climbed after the introduction of concurrent appointments, the city’s reform-related media profile (our proxy for local policy activism) actually fell (see Fig. 3).

Conclusion

The concurrent appointments of a subset of local leaders to higher-level political bodies in Leninist systems like China raise fundamental questions about the extent of top-down political control and bottom-up interest articulation in such systems. In this paper, we have attempted to clarify the function of concurrent leadership appointments in China by applying a novel conceptual framework and exploiting rich evidence from the subnational level. Our quantitative analysis and case studies both show that concurrent appointments of city-level leaders to China’s PPSCs are not simply—or principally—a form of top-down control. Rather, concurrent appointments benefit local interests at least as much as provincial-level interests. While empirical evidence suggests that different intergovernmental dynamics apply to different types of cities, the patterns we document resemble what we call co-optation, compromise, and concession rather than control.

Quantitative analysis of how concurrent appointments affect local policy autonomy and economic outcomes indicates that represented localities enjoy benefits. Cities with concurrently appointed leaders have higher profiles in national media coverage relative to other localities, which we interpret as a sign of heightened local policy activism and/or autonomy. They also display higher rates of GDP growth and higher levels of investment, suggesting that PPSC representation helps localities capture more economic opportunities. However, the consequences of concurrent appointments vary for different types of cities. “Rich” cities with concurrent appointments tend to enjoy enhanced policy autonomy and economic benefits, while “red” cities appear to enjoy more policy autonomy but fewer material benefits. For other cities, the effects of concurrent appointment are less consistent.

Qualitative evidence from the cases of Zhuhai, Ganzhou, and Xiangyang reinforces our quantitative findings while adding more texture to the analysis. Zhuhai, a wealthy coastal city that enjoyed heightened policy autonomy and economic benefits under concurrently appointed leaders, illustrates a concession dynamic. The case of Ganzhou, a city with a renowned revolutionary legacy, reflects a compromise dynamic whereby concurrent appointments bring more local autonomy but less-obvious economic benefits. For Xiangyang, a medium-sized industrial city, concurrent appointments were a form of co-optation, bringing economic benefits but also pressure to execute higher-level policy priorities. While the timing and consequences of concurrent appointments differed widely across the three cases, however, each city appears to have gained more than it lost, whether in the form of expanded policymaking autonomy or additional economic opportunities. Although our case studies and quantitative analysis do not fully resolve the question of whether it is the institutional arrangements or individual leaders put in place through concurrent appointments that drive city-level outcomes, there is preliminary support for an institutional interpretation.

These subnational findings from China imply that concurrent leadership appointments may benefit rather than constrain local interests at other levels of politics in China and in other Leninist systems. When local leaders concurrently sit on higher-level political bodies, their jurisdictions have a greater voice in higher-level deliberations and may benefit in more tangible ways as well. At the national level in China, the examples of Chen Liangyu and Bo Xilai, provincial leaders who held concurrent Politburo seats, show that even actors integrated into the elite level of national politics may prioritize local interests or personal ambitions over higher-level agendas. Outside China, Malesky’s (2008) analysis of Vietnam finds that provinces with “compatriots” serving in the central cabinet enjoy more rather than less policymaking autonomy. From the standpoint of localities, then, the benefits of access to the central leadership often outweigh the closer oversight that comes with such ties.

Beyond showing how concurrent appointments confer advantages on represented localities, this study adds to understanding of China’s contemporary central-local relations. The analysis here provides further evidence of the dynamics of bargaining, reciprocity, and mutual dependency in intergovernmental relations highlighted in previous work by Li (1997), Zheng (2007), Chung (2016), and others. As such work notes, China’s party-state is neither a top-down nor bottom-up political system but instead an elaborate machine for reconciling centralizing and decentralizing impulses. A key attribute of this system, noted by various generations of past scholarship, from Lieberthal and Oksenberg (1988) and Shirk (1993) to Lam (2010) and Heilmann and Perry (2011), is higher-level authorities’ ability to tailor governance practices to varying contexts and to strike “particularistic bargains” with different locales. As we show here, not only are some cities singled out for concurrent leaderships appointments; the implicit privileges and obligations that accompany PPSC representation also vary by city type. Our analysis also adds to scholars’ picture of the interest articulation and representation mechanisms operating in China’s Leninist hierarchy. Whereas Truex (2016) writes of “representation within bounds” in China’s legislatures, cities’ access to party leadership bodies brings the pursuit of local interests to an even more rarefied level of politics.

Notes

All of China’s provincial-level units are represented in the Central Committee of the Communist Party, but the Central Committee is not a standing leadership body with real control over personnel and policy decisions.

Because the leaders of such cities are typically deputy-provincial cadres by default, concurrent appointment to PPSCs does not require a change of rank.

Since 2005, the Chinese government has actively promoted tourism in revolutionary base areas. As discussed in the appendix, we code 13 cities as “red” based on official “red tourism” status. Although we use red tourism status as a proxy for political importance, we do not see tourism itself as what makes these cities important.

This assumes that the error is not correlated with any of the independent variables, which we think is a valid assumption based on the data validation exercise.

Correlations between revenue as a share of GDP, GDP levels, per capita GDP levels, and GDP growth are all very weak, indicating the importance of extraction effort in determining this variable, rather than just increases in economic output.

These cities have concurrent leadership appointments as a rule, and thus offer no variation over time.

This approach also controls for the possibility that the included control variables have disparate effects in different city types.

Note that although we use red tourism as a proxy for political importance, we do not see tourism itself as important. Indeed, most red cities are not among China’s top tourism destinations, and if we substitute a generic tourism proxy into our regressions instead of red city status, the effect on news frequency is significantly negative.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for raising this concern. Theoretically, however, it is also possible that while many leaders hope to distinguish themselves through achievements on the job and thereby improve their chances of promotion, many are not prepared to accept the political risks that accompany high-profile gambits. Young leaders on the fast-track might have less incentive than others to innovate if they are already advancing through the ranks.

Biographical data for all prefecture-level leaders over this time period, including 1567 unique prefecture-level leaders, comes from Blum, Jurgen, David Bulman, Xun Yan, and Qiong Zhang. 2018. “Political Incentives, Firm Support, and Productivity: Evidence from Chinese Cities.” Working Paper.

Based on a preliminary analysis using the case-study localities, we find a range of career backgrounds and promotion trajectories for concurrently appointed city leaders. Although some concurrent appointees, such as Pan Yiyang and Li Jia, have career backgrounds in the Communist Youth League (regarded by some analysts as the base of a large elite political faction), most city-level leaders have no readily discernable factional alignment. Although future work may be able to systematically examine how the factional positioning of city-level leaders affect city performance, data limitations and underdeveloped theory on subnational factionalism make this task difficult. Meanwhile, concurrent appointees in the case-study cities have widely varying career trajectories. Some leaders, such as Shi Wenqing, have risen slowly and steadily through the ranks, while other leaders, such as Fan Ruiping, have progressed more quickly to higher official posts. Some, like Ren Zhenhe, have worked in a single province their whole career; others, like Wang Junzheng, have rotated across provincial lines (China Vitae; Baidu Baike).

Factional ties and innate ability may be indistinguishable as either would be expected to produce the identified city outcomes for the leaders in question prior to PPSC elevation. In other words, if leaders out-performed in their previous posts, this could be due to either patronage or ability—either way, it might imply that individual characteristics are more important than institutional arrangements if these effects persist when these individuals are concurrently appointed to PPSCs.

The small sample also makes difficult a simple dummy variable approach, whereby one could analyze the sample of cities with leaders who rise to the PPSC while in office and regress outcomes on the treatment dummy (PPSC appointment) while controlling for city and year fixed effects. Using our small sample we find no significant results.

References

21 shiji jingji baodao (21 世纪经济报道). 湖北三市‘一把手’高配 (Three Hubei Cities’ Top Leaders Are Concurrently Appointed at Higher Level). 2012. July 13. www.cnki.com.cn.

21 shiji jingji baodao (21 世纪经济报道). 湖北区域协调策:副省级官员主政襄阳宜昌 (Hubei Regional Coordination Strategy: Deputy-Provincial-Level Officials Take Charge of Xiangyang, Yichang). 2013. May 17. www.cnki.com.cn.

Berry CR, Fowler A. Cardinals or clerics? Congressional committees and the distribution of pork. Am J Polit Sci. 2016;60(3):692–708.

Bulman DJ. Incentivized development in China: leaders, governance, and growth in China’s counties. In: Cambridge. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2016.

Bulman DJ, Jaros K. Loyalists, Localists, and Legibility: The Calibrated Control of China’s Provincial Leadership Teams. 2018. Working Paper.

Carsey TM, Rundquist B. Party and Committee in Distributive Politics: evidence from defense spending. The Journal of Politics. 1999;61(4):1156–69.

Chung JH. China’s local governance in perspective: instruments of central control. China J. 2016;75:38–60.

Diyi caijing ribao (第一财经日报). 省级常委兼任 54 城市‘一把手’ (Provincial Party Standing Committee Members Concurrently Appointed as 54 Cities ‘First in Command’). 2014. June 30. www.cnki.com.cn

Falleti T. A sequential theory of decentralization: Latin American cases in comparative perspective. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2005;99(3):327–46.

Heilmann S. From local experiments to National Policy: the origins of China’s distinctive policy process. China J. 2008;59:1–30.

Heilmann S, Perry EJ. Embracing uncertainty: guerrilla policy style and adaptive governance in China. In: Heilmann, Perry, editors. Mao’s invisible hand: the political foundations of adaptive governance in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center; 2011. p. 1–29.

Helmke G, Levitsky S. Informal institutions and comparative politics: a research agenda. Perspect Polit. 2004;2(4):725–40.

Hooghe L, Marks G. Beyond federalism: estimating and explaining the territorial structure of government. Publius: J Federalism. 2013;43(2):179–204.

Huang Y. Inflation and investment controls in China : the political economy of central-local relations during the reform era. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996.

Huang Y, Sheng Y. Political decentralization and inflation: sub-National Evidence from China. Br J Polit Sci. 2009;39(2):389–412.

Hubei ribao (湖北日报). 襄阳OR宜昌,不争‘湖北第二城’,共守第二方阵 (Xiangyang OR Yichang, Not Fighting to Be ‘Hubei’s Second City,’ but Together Serving as a Second Phalanx). 2017. June 30. http://news.cnhubei.com/xw/jj/201706/t3855506.shtml.

Hutchcroft PD. Centralization and decentralization in administration and politics: assessing territorial dimensions of authority and power. Governance. 2001;14(1):23–53.

Interview NC011501b. Author’s interview conducted in Nanchang, Jiangxi; 2015.

Jaros KA. China’s urban champions: the politics of spatial development. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2019.

Jingji ribao (经济日报). Unlock the ‘Magic Cube’ of Marketized Infrastructure Operation (寻找基础设施市场化运作的 ‘魔方’)’. 2002. September 13. www.cnki.com.cn.

Lam T-c. Institutional constraints, leadership, and development strategies: Panyu and Nanhai under reform. In: Chung, editor. Cities in post-Mao China: recipes of economic development in the reform era. London: Routledge; 1999. p. 256–95.

Lam T-c. Central-provincial relations amid greater centralization in China. China Information. 2010;24:339–63.

Landry PF. Decentralized authoritarianism in China: the Communist Party’s control of local elites in the post-Mao era. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Landry PF, Lv X, Duan H. Does performance matter? Evaluating political selection along the Chinese administrative ladder. Comp Pol Stud. 2018;51(8):1074–105.

Lane D. State and politics in the USSR. Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 1985.

Lieberthal K, Oksenberg M. Policy making in China: leaders, structures, and processes. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1988.

Li C. The leadership of China’s four major cities: a study of municipal party standing committees. China Leadership Monitor. 2007; 31. www.hoover.org.

Li C. Chinese Leadership in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press; 2016.

Li LC. Provincial discretion and national power: investment policy in Guangdong and Shanghai, 1978-93. China Q. 1997;152:778–804.

Looney K. The Rural Developmental State: Modernization Campaigns and Peasant Politics in China, Taiwan, and South Korea. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University; 2012.

Looney K. China’s campaign to build a new socialist countryside: village modernization, peasant councils, and the Ganzhou model of rural development. China Q. 2015;224:909–32.

Ma X. Guardians and Gridlock: Bureaucracy, Bargaining, and Authoritarian Policymaking. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Political Science, University of Washington; 2017.

Malesky EJ. Straight ahead on red: how foreign direct investment empowers subnational leaders. J Polit. 2008;70(1):97–119.

Nanfang ribao (南方日报). The Time Has Come for Zhuhai’s Development (珠海发展正当时 回国创业促腾飞). 2015. September 21. www.cnki.com.cn.

Ngo T-W, Cunyi Y, Zhilin T. Scalar restructuring of the Chinese state: the subnational politics of development zones. Econ Plan C: Polit Space. 2017;35(1):57–75.

Renmin ribao (人民日报). 江西赣州贯彻落实《国务院关于支持赣南等原中央苏区振兴发展的若干意见》纪实 (Jiangxi’s Ganzhou Fully Implements State Council Opinion on Soviet Area Revival). 2014a. March 13. http://jx.people.com.cn/n/2014/0313/c190262-20762970.html.

Renmin ribao (人民日报). 赣南 当振兴成为信念 (Southern Jiangxi: Believing in Revival). 2014b. August 14. http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrb/html/2014-08/14/nw.D110000renmrb_20140814_2-01.htm.

Sheng Y. Authoritarian co-optation, the territorial dimension: provincial political representation in post-Mao China.(report). Stud Comp Int Dev (SCID). 2009;44(1):71–93.

Sheng Y. Economic openness and territorial politics in China. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

Sheng N, Tang UW. Zhuhai: City profile. Cities. 2013;32:70–9.

Shih VC. Factions and finance in China: elite conflict and inflation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Shi Y. The impact of urban administrative institution reforms and division adjustments on urbanization in China. In: Challenges in the Process of China’s Urbanization, 75–90. Stanford: Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center Books; 2017.

Shirk SL. The political logic of economic reform in China. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1993.

Tan, Qingshan. China’s Provincial Party Secretaries. EAI Background Brief, No. 195–196. Singapore: East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore; 2004.

Tarrow S. Introduction. In: Territorial Politics in Industrial Nations, 1–27. New York: Praeger Publishers; 1978.

Truex R. Making autocracy work: representation and responsiveness in modern China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2016.

Wang Y, Minzner C. The rise of the Chinese security state. China Q. 2015;222:339–59.

Xin jing bao (新京报). ‘红色城市’一把手为何高配? (Why Are ‘Red Cities’ Top Leaders Concurrently Appointed to Higher Party Rank?). 2015. June 18. http://www.bjnews.com.cn/news/2015/06/18/367602.html.

Xu, Jiang, and Anthony G. O. Yeh. “Interjurisdictional Cooperation through Bargaining: The Case of the Guangzhou–Zhuhai Railway in the Pearl River Delta, China. 2013; 213: 130–51.

Zheng Y. De facto federalism in China : reforms and dynamics of central-local relations. Hackensack: World Scientific; 2007.

Zhongguo haiyang bao (中国海洋报). Coastal city development should achieve an ecological economy Win-Win (沿海城市发展应实现生态经济双赢). 2014. September 5. www.cnki.com.cn.

Zhongguo xinxi bao (中国信息报). Ganzhou uses its full strength to build a new economic strong city (赣州全力打造新经济强市). 2003. March 15. www.cnki.com.cn.

Zhuhai tequ bao (珠海特区报). ‘Zhuhai will create a Chinese Yacht capital 珠海将打造中国游艇之都. 2013. June 17. www.cnki.com.cn.

Zhuhai tequ bao (珠海特区报). Choose Zhuhai and move toward the world (选择珠海走向世界). 2014. March 10. www.cnki.com.cn.

Zhuhai tequ bao (珠海特区报). Zhuhai will build a maritime economy ecological demonstration city (珠海将建海洋经济生态示范市). 2015. November 16. www.cnki.com.cn.

Acknowledgements

This article benefited from the constructive criticism of several colleagues and the helpful feedback of anonymous reviewers. We would especially like to recognize suggestions and input of Daniel Koss, Alisha Holland, Brian Palmer-Rubin, Yanilda Gonzalez, and Emily Clough. We would also like to recognize the excellent research assistant work of Gary Wang and Shijia Yao. All mistakes are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Statistical Appendix for “Leninism and Local Interests”

Appendix: Statistical Appendix for “Leninism and Local Interests”

-

1.

Data: sources and summary statistics

-

2.

Constructing and validating the policy autonomy proxy

-

3.

Which cities get selected to have concurrent appointments?

-

4.

Robustness checks for baseline results (Table 2)

-

5.

Regression results by city type

-

6.

Causal mechanisms: institutions versus individuals

1. Data: sources and summary statistics

This paper relies on four general sets of data. First, data on which cities have concurrent appointments in any given year come a novel collection of data about the makeup of China’s provincial party standing committees (PPSCs) and the personal and career backgrounds of PPSC members, introduced in Bulman and Jaros (2018). The dataset spans the years from 1996 to 2013, and contains detailed information on 1443 unique PPSC members. Information on the composition of PPSCs was obtained from annual editions of the China Directory series published by Radiopress, Inc. To supplement these name lists, biographical and career data were gathered from Baidu Online Encyclopedia (百度百科), available at baike.baidu.com. Where information was unavailable on Baidu Online Encyclopedia, additional searches were conducted using (1) Xinhua Net (news.xinhuanet.com), (2) China Vitae (www.chinavitae.com), and/or (3) China Political Elite Database (http://cped.nccu.edu.tw/). For the purposes of this paper, there are two relevant variables: the concurrent position of PPSC members (except for party secretaries and deputy party secretaries, all other PPSC members tend to have at least one other concurrent party or government position); and, when the concurrent position is a prefectural-level city party secretary post, the name of the city.