Abstract

Much of the theoretical work on preferences for redistribution begins with the influential Melzer–Richard model, which makes predictions derived both from position in the income distribution and the overall level of inequality. Our evidence, however, points to limitations on such models of distributive politics. Drawing on World Values Survey evidence on preferences for redistribution in 41 developing countries, we find that the preferences of low-income groups vary significantly depending on occupation and place of residence, union members do not hold progressive views, and inequality has limited effects on demands for redistribution and may even dampen them.

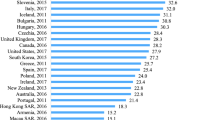

Marginal Effect of Manual Workers on Preferences for Redistribution as Capshare Increases (Model 5, Table 5)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In earlier versions, we also controlled for GDP. This, however, had no effect and for clarity of presentation, we do not show results here.

For contrasting perspectives on these questions, however, see models of relative deprivation by Gurr (1970) and Hirschman and Rothchild (1973) that suggest resentment can arise even when material conditions are improving. More recently, Reenock et al. (2007) find empirical support that “regressive socioeconomic development”—increasing wealth combined with continuing poverty—is positively linked to political conflict and the breakdown of democracies.

The countries in the sample are Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Chile, China, Colombia, Cyprus, Egypt, Ethiopia, Georgia, Ghana, Guatemala, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Malaysia, Mali, Mexico, Moldova, Morocco, Peru, Poland, Romania, Russia, Rwanda, Serbia, Slovenia, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, Ukraine, Uruguay, Vietnam, and Zambia.

The single exception is with respect to our findings on manual and agricultural labor reported in Table 4, which fail to reach standard levels of significance. Results from the alternative specifications are available on request from the authors.

Put differently, multilevel modeling provides a way for researchers to address the problem of “clustering” that arises because individual responses are not independent of each other within certain clusters (Primo, Jacobsmeier, and Milyo 2007). Without correcting for intracluster correlation, results underestimate the size of standard errors and therefore overpredict p values and significance even though the true number of observations is closer to the number of clusters (countries) rather than the number of individual survey responses. Simply clustering standard errors by country, however, does not allow us to incorporate level 2 variables or to perform cross-level interactions.

In addition to the findings on manual workers discussed here, Table 7 shows that the coefficient on the interaction between capshare and “big-city” manual workers is negative, although not statistically significant.

References

Acemoglu D, Robinson J. Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

Alesina A, Giuliano P. Preferences for redistribution. Working paper 14825. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2009.

Alesina A, Glaeser EL. Fighting poverty in the US and Europe: a world of difference. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004.

Amat F, Wibbels E. Electoral incentives, group identity and preferences for redistribution. Madrid: Instituto Juan March de Estudios e Investigaciones, Working Paper 2009/246 (December) 2009.

Ansell B, Samuels, D. Inequality and democratization: individual-level evidence of preferences for redistribution under autocracy. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Seattle, Washington, August 31 to September 4; 2011.

Bartels L. Unequal democracy: the political economy of the new gilded age. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2008.

Bates R. Markets and states in tropical Africa. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1981.

Benabou R, Ok EA. Social mobility and the demand for redistribution: the POUM hypothesis. Q J Econ. 2001;116(2):447–87.

Boix C. Democracy and redistribution. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

Breen R. Foundations of a neo-Weberian class analysis. In: Olin Wright E, editor. Approaches to class analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Cramer BD, Kaufman RR. Views of economic inequality in Latin America. Comp Polit Stud. 2011;44(9):1206–37.

Cusack T, Iversen T, Rehm P. Risks at work: the demand and supply sides of government redistribution. Oxford Rev Econ Policy. 2006;22:365–89.

de la OA, Rodden J. Does religion distract the poor? Income and issue voting around the world. Comp Polit Stud. 2008;41:437–76.

Dollar D, Kraay A. Growth is good for the poor. J Econ. 2002;7:195–225.

Erikson R, Goldthorpe JH. The constant flux: a study of class mobility in industrial societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993.

Esping-Anderson G. Politics against markets. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1985.

Finseraas H. Income inequality and demand for redistribution: a multilevel analysis of european public opinion. Scand Polit Stud. 2008;32(1):94–119.

Gurr TR. Why men rebel. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1970.

Haggard S, Kaufman RR. Development, democracy and welfare states: Latin America, East Asia and Eastern Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2008.

Hirschman AO, Rothschild M. The changing tolerance of income inequality in the course of economic development. Q J Econ. 1973;87(4):544–66.

Honaker J, King G, Blackwell M. Amelia II: a program for missing data. 2009. http://gking.harvard.edu/amelia. Accessed 15 Oct 2012.

Houle C. Inequality and democracy: why inequality harms consolidation but does not affect democratization. World Polit. 2009;61:4(October):589–622.

Huber E, Stephens JD. Democracy and the left: social policy and inequality in Latin America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2012.

Iversen T, Soskice D. An asset theory of social policy preferences. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2001;95:875–95.

Kenworthy L, McCall L. Inequality, public opinion and redistribution. Socio-Econ Rev. 2008;6(1):35–68.

King G, Honaker J, Joseph A, Scheve K. Analyzing incomplete political science data: an alternative algorithm for multiple imputation. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2001;95(1):49–69.

Korpi W. The democratic class struggle. London: Routledge; 1983.

Lipton M. Why poor people stay poor: urban bias in world development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1977.

Martin N, Brady D. Workers of the less developed world unite? A multi-level analysis of unionization in less developed countries. Am Sociol Rev. 2007;72:562–84.

Meltzer AH, Richard SF. A rational theory of the size of government. J Polit Econ. 1981;89(5):914–27.

Moene KO, Wallerstein M. Earnings inequality and welfare spending: a disaggregated analysis. World Polit. 2003;55(July):485–516.

Portes A, Hoffman K. Latin American class structures: their composition and change during the neoliberal era. Lat Am Res Rev. 2003;38:41–82.

Primo DM, Jacobsmeier ML, Jeffrey M. Estimating the impact of state policies and institutions with mixed-level data. State Polit Pol Q. 2007;7(4):446–59. Winter.

Reenock C, Bernhard M, Sobek D. Regressive socioeconomic distribution and democratic survival. Int Stud Q. 2007;51(3):677–99.

Rehm D. Risks and redistribution: an individual-level analysis. Comparative Political Studies. 2009;42(7):855–81.

Rudra N. Globalization and the race to the bottom in developing countries: who really gets hurt? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Scheve K, Stasavage D. Religion and preferences for social insurance. Q J Polit Sci. 2006;1(3):255–86.

Solt F. Economic inequality and democratic political engagement. Am J Polit Sci. 2008;52(1):48–60.

Solt F. Standardizing the world income inequality database. Soc Sci Q. 2009;90(2):231–42.

Solt F. Does economic inequality depress electoral participation? Testing the Schattschneider hypothesis. Polit Behav. 2010;32(2):285–301.

Sorenson A. Toward a sounder basis for class analysis. Am J Sociol. 2000;105(6):1523–58. May.

Stephens JD. The transition from capitalism to socialism. London: Macmillan; 1979.

Svallfors S. Worlds of welfare and attitudes to redistribution: a comparison of eight Western nations. Eur Sociol Rev. 1997;13:283–304.

Svallfors S. The moral economy of class: class and attitudes in comparative perspective. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2006.

University of Texas Inequality Project. 2010. Estimated household inequality data set. http://utip.gov.utexas.edu/data.html. Accessed 1 May 2009.

World Bank. The World Development Indicators. 2008.

Wright EO, editor. Approaches to class analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haggard, S., Kaufman, R.R. & Long, J.D. Income, Occupation, and Preferences for Redistribution in the Developing World. St Comp Int Dev 48, 113–140 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-013-9129-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-013-9129-8