Abstract

We compare the employment of African American and white youth as they transition to adulthood from age 18 to 22, focusing on high school graduates and high school dropouts who did not attend college. Using OLS and hazard models, we analyze the relative employment rates, and employment consistency, stability, and timing, controlling for a number of factors including family income, academic aptitude, prior work experience, and neighborhood poverty. We find white high school graduates work significantly more than all other youth on most measures; African American high school graduates work as much and sometimes less than white high school dropouts; African American dropouts work significantly less than all other youth. Findings further suggest that the improved labor market participation associated with a high school diploma is higher over time for African Americans than for white youth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

One element of Heckman’s (1998) criticism is that employers and audit-study designers may be attuned to different observable characteristics—and while audit studies match fake job applicants on one set (e.g., résumé, attire, comportment), employers may observe and focus on additional features, still unrelated to race, that study-designers may not know or match on. Therefore, the job applicants are not truly identical from an employer’s perspective.

Youth who graduate from high school after their 18th birthday may be at a disadvantage relative to other youth in the employment outcome variables, which are measured from the 18th birthday. To determine whether this effect is significant, we performed a sensitivity analysis by adding a control variable for the number of months after age 18 that a youth graduated from high school. This variable was set to zero for drop outs and youth who graduated before they turned 18 (since these youth would not be in school when their employment outcomes were measured). Qualitatively, the results for all of the sensitivity analyses were identical to the analyses presented here, suggesting that the birth dates of the youth had no impact on the analyses. In some cases the estimated coefficients changed by adding this control variable, but none of the conclusions of the paper, and none of the disparities between white graduates, white drop outs, African American graduates, and African American drop outs reported in the paper changed in the sensitivity analyses.

As a robustness check, the regression models were also conducted using a censored normal model and a negative binomial model. African American graduates and dropouts, as well as white dropouts performed substantially worse than white graduates in all of these models, relative to the OLS models presented in the paper. In that sense, the results presented in this paper represent the most conservative results produced out of all the model specifications that were conducted. Censored normal and negative binomial results are available from the authors on request.

As a robustness check, the accelerated failure time models were also conducted using the log-logistic distribution. None of the qualitative results changed as a result, although estimated time to failure relative to the reference group of white high school graduates was somewhat longer. Therefore, the Weibull distribution results reported here can be considered conservative estimates of racial disparities in time until employment. Log-logistic distribution results are available from the authors on request.

References

Allison P. Event history and survival analysis using STATA. Unpublished Summer 2008 Course Guide; 2008.

Arnett JJ. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood: perspectives from adolescence to midlife. Journal of Adult Development. 2001;8:133–43.

Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: what is it, and what is it good for? Child Development, Perspectives. 2007;1(2):68–73.

Arrow K. The Theory of Discrimination. In: Ashenfelter O, Rees A, editors. Discrimination in labor markets. Princeton: Princeton University; 1973.

Aud S, Hussar W, Planty M, Snyder T, Bianco K, Fox M, Frohlich L, Kemp J, Drake L. The condition of education 2010: National center for education statistics. Washington D.C: U.S. Department of Education; 2010.

Becker G. The economics of discrimination. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1957.

Bell L, Burtless G, Gornick J, Smeeding T. Failure to Launch: Cross- National Trends in the Transition to Economic Independence. In: Danziger S, Rouse CE, editors. The price of independence: the economics of early adulthood. New York, NY: The Russell Sage Foundation; 2007. p. 27–55.

Belman D, Heywood J. Sheepskin effects in the returns to education: an examination of women and minorities. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 1991;73(4):720–4.

Belman D, Heywood J. Sheepskin effects by cohort: implications of job matching in a signaling model. Oxford Economics Papers. 1997;49(4):623–37.

Berwick DM, Murphy JM, Goldman PA, Ware JE Jr, Barsky AJ, Weinstein MC. Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Medical Care. 1991;29(2):169–76.

Black D, Haviland A, Sanders S, Taylor L. Why do minority men earn less? A study of wage differentials among the highly educated? The Review of Economics and Statistics. 2006;88:300–13.

Borjas G, Grogger J, Hanson G. Immigration and the economic status of African American men. Economica. 2010;77(306):255–82.

Cameron S, Heckman J. The non-equivalence of high school equivalents. Journal of Labor Economics. 1993;11(1):1–47.

Couch K, Fairlie R. Last hired, first fired? Black-white unemployment and the business cycle. Demography. 2010;47(1):227–47.

Day J, Newburger E. The big payoff: educational attainment and synthetic estimates of work-life earnings. Curr Popul Rep. 2002;23–210.

Farrington D, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van-Kammen W, Schmidt L. Self-reported delinquency and a combined delinquency seriousness scale based on boys, mothers, and teachers: concurrent and predictive validity for African-Americans and Caucasians. Criminology. 1996;34(4):493–518.

Finn J. The adult lives of at-risk students: the roles of attainment and engagement in high school. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education; 2006.

Goldin C, Katz L. Long-run changes in the wage structure: narrowing, widening, and polarizing. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 2007;2(2007):135–65.

Goldin C, Katz L. The race between education and technology. Cambridge: The Belknap Press; 2008.

Granovetter M. Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology. 1985;19:481–510.

Gresenz C, Sturm R. Mental health and employment transitions. In D Marcotte, V Wilcox-Gök, editors. Research in human capital and development. 2004;15:95–108.

Heckman JJ. Detecting discrimination. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1998;12(2):101–16.

Heckman J, Humphries J, Mader M. The GED. NBER WP No. 16064; 2010.

Holzer H. The labor market and young black men: updating Moynihan’s perspective. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2009;621(1):47–69.

Holzer H. Is the middle of the U.S. job market really disappering?: A comment on the “polarization” hypothesis”. Washington, D.C: Center for American Progress; 2010.

Holzer H, Hlavac M. A Very Uneven Road: U.S. Labor Markets in the Past 30 Years. In Logan JR, editors. The lost decade? Social changes in the US after 2000. Russell Sage Foundation; 2012.

Holzer H, Lerman R. America’s forgotten middle-skill jobs. Washington, D.C: Skills 2 Compete; 2007.

Holzer H, Offner P. Trends in the employment outcomes of young Black men: 1979–2000. In: Mincy R, editor. Black males left behind. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press; 2006. p. 1–10.

Holzer H, Offner P, Sorenson E. Declining employment among young Black less-educated men: the role of incarceration and child support. Journal of Public Policy Analysis and Management. 2005;2005:24(2).

Lacey TA, Wright B. Occupational employment projections to 2018. Monthly Labor Review. 2009;2009:82–99.

Lang K. Poverty and discrimination. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2007.

Lang K, Lehman JK. Racial discrimination in the labor market: Theory and empirics. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working paper 17450. 2011. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17450, accessed September 2012.

Mason P. Persistent racial discrimination in the labor market. In: Conrad C, Whitehead J, Mason P, Stewart J, editors. African Americans in the U.S. Economy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc; 2005. p. 133–141.

McElroy SW. Race and gender differences in the U.S. labor market: The impact of educational attainment. In: Conrad C, Whitehead J, Mason P, Stewart J, editors. African Americans in the U.S. Economy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.; 2005. p. 133–141.

McKinley L, Blackburn M, Neumark D. Are OLS estimates of the return to schooling biased downward? Another look. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 1995;77(2):217–30.

Mincy R, Lewis CE, Han W. Left Behind: Less-Educated Young Black Men in the Economic Boom of the 1990s. In: Mincy R, editor. Black males left behind. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press; 2006. p. 1–10.

Mortimer J, Vuolo M, Staff J, Wakefield S, Xie W. Tracing the timing of “career” acquisition in a contemporary youth cohort. Work and Occupations. 2008;35(1):44–84.

Neal D. Why has black-white skill convergence stopped?. In: Hanushek, E, Welch F, editors. Handbook of the Economics of Education. Elsevier B.V.; 2006. p. 511–576.

Neal D, Johnson W. The role of premarket factors in black-white wage differences. Journal of Political Economy. 1996;104:869–95.

Osgood DW, Ruth G, Eccles JS, Jacobes JE, Barber BL. Six paths to adulthood: Fast starters, parents without careers, educated partners, educated singles, working singles, and slow starters. In: Settersten R, Furstenberg F, Rumbaut R, editors. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. The University of Chicago Press; 2005. p. 320–355.

Ostroff J, Woolverton KS, Berry C, Lesko LM. Use of the mental health inventory with adolescents: a secondary analysis of the RAND health insurance study. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8(1):105–7.

Pager D, Western B, Bonikowski B. Discrimination in a low-wage labor market: a field experiment. American Sociological Review. 2009;74(5):777–99.

Phelps E. The statistical theory of racism and sexism. The American Economic Review. 1972;62(4):659–61.

Raaum O, Røed K. Do business cycle conditions at the time of labor market entry affect future employment prospects? The Review of Economics and Statistics. 2006;88(2):193–210.

Ritter J, Taylor L. Racial disparity in unemployment. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 2011;93(1):30–42.

Royster D. Race and the invisible hand. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2003.

Spence M. Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1973;87(3):355–74.

Stoll M. The black youth employment problem revisted. In: Conrad C, Whitehead J, Mason P, Stewart J editors. African Americans in the U.S. Economy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.; 2005. p. 133–141.

Thornberry T, Krohn M. Comparison of self-report and official data for measuring crime. In: Pepper J, Petrie C, editors. Measurement problems in criminal justice research: workshop summary. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2003.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Amerca’s youth at 22: school enrollment, training, and employment transitions between ages 21 and 22. 2010; Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/nlsyth_01282010.pdf. On 5/23/2011.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Education Pays. 2011a. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_chart_001.htm. On 5/23/2011.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Table A-4: Employment Status of the civilian population 25 years and over by educational attainment. 2011b. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t04.htm. On 5/23/2011.

Wilson W. When work disappears. New York: Alfred Knopf; 1996.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We are extremely grateful to Harry Holzer, Margaret Simms and Ajay Chaudry, and our anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback on earlier drafts. We would also like to thank Jennifer Macomber and Michael Pergamit for motivating our research through their leadership on a companion research project using the 1997 NLSY. The study was supported by the Annie E. Casey Foundation through the Urban Institute’s Low Income Working Families project. The findings and conclusions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Annie E Casey Foundation, or the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its sponsors.

Appendix

Appendix

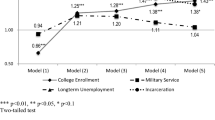

Consistent with prior work on the treatment of the GED in the labor market (Cameron and Heckman 1993; Heckman et al. 2010), this study has categorize GED recipients as dropouts. This is not the only possible categorization of GED holders. The appendix presents results of the full model (Model 4) presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4 after separating GED holders from dropouts. All of the covariates held constant in Model 4 of Tables 2, 3, and 4 are controlled for in Table 5, but their coefficients are not presented here.

Almost all of the findings from the models that included GED holders with dropouts are maintained in Table 5. The difference in employment between African American graduates and dropouts is still wider than the gap between white graduates and white dropouts at age 18 and age 22, with the greatest difference appearing by age 22, suggesting that a high school diploma confers even greater employment benefits on African American youth than white youth. One difference with that emerges when GED earners are separated from dropouts is that white dropouts have lower employment rates than white graduates at age 22. When GED earners were included in this category, white dropouts and graduates performed comparably in employment at age 22. This suggests that white GED holders have better employment outcomes than white dropouts (although still not as strong as white high school graduates). However, the racial difference in the employment effect of a high school diploma is maintained.

About this article

Cite this article

McDaniel, M., Kuehn, D. What Does a High School Diploma Get You? Employment, Race, and the Transition to Adulthood. Rev Black Polit Econ 40, 371–399 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12114-012-9147-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12114-012-9147-1