Abstract

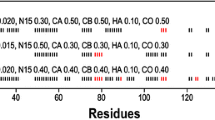

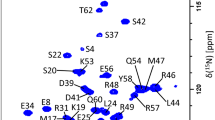

Human uracil N-glycosylase isoform 2—UNG2 consists of an N-terminal intrinsically disordered regulatory domain (UNG2 residues 1–92, 9.3 kDa) and a C-terminal structured catalytic domain (UNG2 residues 93–313, 25.1 kDa). Here, we report the backbone 1H, 13C, and 15N chemical shift assignment as well as secondary structure analysis of the N-and C-terminal domains of UNG2 representing the full-length UNG2 protein.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- SLIC:

-

Sequence- and ligation independent cloning

- UNG2:

-

Uracil N-glycosylase isoform 2

- N-UNG2:

-

Residues 1–92 of UNG2

- AA:

-

Amino acid

- PCNA:

-

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- RPA:

-

Replication protein A

- CBD:

-

Chitin binding domain

- C-UNG2:

-

Residues 93–313 of UNG2-G93C

References

Assefa NG, Niiranen L, Willassen NP, Smalås A, Moe E (2012) Thermal unfolding studies of cold adapted uracil-DNA N-glycosylase (UNG) from Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). A comparative study with human UNG comparative biochemistry and physiology part. Biochem Mol Biol 161:60–68. doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2011.09.007

Blatny JM, Brautaset T, WintherLarsen HC, Karunakaran P, Valla S (1997) Improved broad-host-range RK2 vectors useful for high and low regulated gene expression levels in gram-negative bacteria. Plasmid 38:35–51

Hagen L et al (2008) Cell cycle-specific UNG2 phosphorylations regulate protein turnover, activity and association with RPA. EMBO J 27:51–61. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601958

Kavli B et al (2002) hUNG2 Is the Major repair enzyme for removal of uracil from U:A matches, U:G mismatches, and U in single-stranded DNA, with hSMUG1 as a broad specificity backup. J Biol Chem 277:39926–39936. doi:10.1074/jbc.M207107200

Keller R (2004) Optimizing the process of nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum analysis and computer aided resonance. Assignment CANTINA Verlag, Zürich

Li MZ, Elledge SJ (2012) SLIC: a method for sequence- and ligation-independent cloning. In: Peccoud J (ed) Gene synthesis: methods and protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, pp 51–59. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-564-0_5

Marsh JA, Singh VK, Jia Z, Forman-Kay JD (2006) Sensitivity of secondary structure propensities to sequence differences between α- and γ-synuclein. Implic Fibril Protein Sci 15:2795–2804. doi:10.1110/ps.062465306

Mer G et al (2000) Structural basis for the recognition of DNA repair proteins UNG2, XPA, and RAD52 by replication factor RPA. Cell 103:449–456. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00136-7

Mol CD, Arvai AS, Slupphaug G, Kavli B, Alseth I, Krokan HE, Tainer JA (1995) Crystal structure and mutational analysis of human uracil-DNA glycosylase: structural basis for specificity and catalysis. Cell 80:869–878

Otterlei M et al. (1999) Post-replicative base excision repair in replication foci. EMBO J. doi:10.1093/emboj/18.13.3834

Shen Y, Delaglio F, Cornilescu G, Bax A (2009) TALOS+: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J Biomol NMR 44:213–223. doi:10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z

Sletta H et al (2007) The presence of N-terminal secretion signal sequences leads to strong stimulation of the total expression levels of three tested medically important proteins during high-cell-density cultivations of Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:906–912. doi:10.1128/AEM.01804-06

Slupphaug G, Mol CD, Kavli B, Arvai AS, Krokan HE, Tainer JA (1996) A nucleotide-flipping mechanism from the structure of human uracil-DNA glycosylase bound to DNA. Nature 384:87–92. doi:10.1038/384087a0

Studier FW (2005) Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein Expr Purif 41:207–234

Zhang H, Neal S, Wishart DS (2003) RefDB: a database of uniformly referenced protein chemical shifts. J Biomol NMR 25:173–195

Acknowledgements

This work was financed by the MARPOL project, the Norwegian NMR Platform and a FRINAT project, all from the Research Council of Norway (Grant Numbers 221576, 226244, and 221538, respectively).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Buchinger, E., Wiik, S.Å., Kusnierczyk, A. et al. Backbone 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift assignment of full-length human uracil DNA glycosylase UNG2. Biomol NMR Assign 12, 15–22 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12104-017-9772-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12104-017-9772-5