Abstract

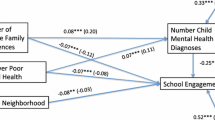

Social science has frequently examined the relationships between school environment and delinquency, mental health and delinquency, and school environment and mental health. However, little to no research to date has examined the interrelationship between these variables simultaneously, especially at it relates specifically to delinquent acts committed at school. The current study uses data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) to look at the interrelationship between these variables. What is found in this data is that the relationship between negative mental health states and delinquency at school, specifically measured as depressive symptoms and gun carrying at school, respectively, is possibly a spurious one, wherein both of these variables are partly shaped by school attachment, which accounts for their correlation. Implications for theory and policy are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While this study will invoke many of the concepts found in general strain theory, we do not use general strain theory as a theoretical guide, because rather than focusing on a lack of school attachment as a strain that increases negative emotions which then result in deviance (i.e., the mediating relationship general strain theory proposes), we instead focus on and find that the negative emotions-deviance relationship is a spurious one, with school attachment as the key confounding variable.

Given the rarity of the dependent variable, rare events logit estimation was considered. However, this is not an option in Stata 13.1 when the “svyset” command is used to correct for sampling design to unbias coefficients, and thus standard logit estimation was utilized. If the models are run without the “svyset” command, which is not advised by Add Health, and the “firthlogit” command is used to run a type of rare events logit estimation, results that are substantively identical to those presented in this paper are produced. These results are available upon request.

For example, while later waves of data have better questions concerning anger, the only one available in Waves I and II comes from the parent interview in Wave I, where the target respondent’s parent was asked, “Does your child have a bad temper?” Responses were simply recorded as “yes” or “no.”

While there is a large age range in Add Health, the vast majority (88.6%) of respondents were between 14 and 18 years old at Wave II.

Regression models run with additional SES controls for parental education, parental employment, and total family income produce identical results for the key variables of interest. With these SES measures infrequently showing statistical significance and having little impact on the results, a more parsimonious model with only the public assistance variable is presented. Results with all of these SES measures included are available upon request.

For these OLS models we computed the ln + 1 of the depression variable to smooth out the distribution. For this logged variable, skewness = −.81 and kurtosis = .77.

These variables, and guidance on how to appropriately use them, are provided by Add Health. Specifically, Add Health respondents have an individual weighting variable, a cluster variable based on their school, and a stratification variable based on their census region. These variables are identified in Stata 13.1 by using the “svyset” command.

Stata 13.1 will not produce standardized (beta) coefficients for regression models that have been “svyset.” This is for statistical reasons. Stata 13.1 and other programs are only willing to consider variance decomposition when data are understood to be independent and identically distributed (IID). Using the “svyset” command is specifically meant to correct for the data not being IID, therefore Stata 13.1 is unwilling to consider ratios of variance in these models.

When data are “svyset” in Stata 13.1, the M & Z pseudo r-sq. value is the only one of the numerous possible pseudo r-sq. values that is presented when using the “fitstat” command after running a logistic regression model.

Traditional tests of model fit improvement, such as the likelihood ratio test or Wald test, will not run in STATA when data is “svyset.” However, if the models are run without the “svyset” command, which is not recommended in the case of these data, the likelihood ratio test produces a significant chi-square statistic suggesting model fit improvement when school attachment is considered between models 1 and 3 (chi-sq. = 65.81, prob. > chi-sq. = 0.0000), and models 2 and 4 (chi-sq. = 26, prob. > chi-sq. = 0.0000).

Several alternative moderator and mediator models were considered, none of which fit the data as well as the presented models. School attachment and depressive symptoms did not significantly interact in their association with gun carrying at school, at Waves I or II. Also, mediating models were not supported. When controlling for school attachment at Wave I, depressive symptoms, at Waves I and II, do not significantly relate to gun carrying. Also, controlling for depressive symptoms does nothing to change the magnitude of the relationship of school attachment, at Waves I or II, with gun carrying. Results are available upon request.

References

Agnew, R., Brezina, T., Wright, J. P., & Cullen, F. T. (2002). Strain, personality traits, and delinquency: Extending general strain theory. Criminology, 40(1), 43–72.

Akers, R. L., & Sellers, C. S. (2016). Criminological theories : Introduction, evaluation, and application (7th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Bailey, S. L., Flewelling, R. L., & Rosenbaum, D. P. (1997). Characteristics of students who bring weapons to school. Journal of Adolescent Health, 20(4), 261–270.

Beardslee, J., Docherty, M., Mulvey, E., Schubert, C., & Pardini, D. (2017). Childhood risk factors associated with adolescent gun carrying among black and white males: An examination of self-protection, social influence, and antisocial propensity explanations. Law and Human Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000270.

Beaver, K. M., Wright, J. P., & DeLisi, M. (2008). Delinquent peer group formation: Evidence of a gene X environment correlation. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 169(3), 227–244.

Blumstein, A., & Cork, D. (1996). Linking gun availability to youth gun violence. Law and Contemporary Problems, 59(1), 5–24.

Bond, L., Butler, H., Thomas, L., Carlin, J., Glover, S., Bowes, G., & Patton, G. (2007). Social and school connectedness in early secondary school as predictors of late teenage substance use, mental health, and academic outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(4), 357–3e9.

Borum, R., Cornell, D. G., Modzeleski, W., & Jimerson, S. R. (2010). What can be done about school shootings? A review of the evidence. Educational Researcher, 39(1), 27–37.

Brockenbrough, K. K., Cornell, D. G., & Loper, A. B. (2002). Aggressive attitudes among victims of violence at school. Education and Treatment of Children, 25(3), 273–287.

Burgess, A. W., Garbarino, C., & Carlson, M. I. (2006). Pathological teasing and bullying turned deadly: Shooters and suicide. Veictims and Offenders, 1(1), 1–14.

Cernkovich, S. A., & Giordano, P. C. (1992). School bonding, race, and delinquency. Criminology, 30(2), 261–291.

Chapple, C. L., Tyler, K. A., & Bersani, B. E. (2005). Child neglect and adolescent violence: Examining the effects of self-control and peer rejection. Violence and Victims, 20(1), 39–53.

Cornell, D. (2006). School violence: Fears vs facts. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dornbusch, S. M., Erickson, K. G., Laird, J., & Wong, C. A. (2001). The relation of family and school attachment to adolescent deviance in diverse groups and communities. Journal of Adolescent Research, 16(4), 396–422.

DuRant, R. H., Krowchuk, D. P., Kreiter, S., Sinal, S. H., & Woods, C. R. (1999). Weapon carrying on school property among middle school students. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 153(1), 21–26.

Esselmont, C. (2014). Carrying a weapon to school: The roles of bullying victimization and perceived safety. Deviant behavior, 35(3), 215–232.

Forrest, K. Y., Zychowski, A. K., Stuhldreher, W. L., & Ryan, W. J. (2000). Weapon-carrying in school: Prevalence and association with other violent behaviors. American Journal of Health Studies, 16(3), 133.

Fox, C., & Harding, D. J. (2005). School shootings as organizational deviance. Sociology of Education, 78(1), 69–97.

van Geel, M., Vedder, P., & Tanilon, J. (2014). Bullying and weapon carrying: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(8), 714–720.

Goodman, E., Slap, G. B., & Huang, B. (2003). The public health impact of socioeconomic status on adolescent depression and obesity. American Journal of Public Health, 93(11), 1844–1850.

Hallfors, D. D., Waller, M. W., Ford, C. A., Halpern, C. T., Brodish, P. H., & Iritani, B. (2004). Adolescent depression and suicide risk: Association with sex and drug behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27(3), 224–231.

Hallfors, D. D., Waller, M. W., Bauer, D., Ford, C. A., & Halpern, C. T. (2005). Which comes first in adolescence—Sex and drugs or depression? American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 29(3), 163–170.

Harris, K. M., Florey, T., Tabor, J., Bearman, P. S., Jones, J., & Udry, J. R. (2003). The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research design. Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

Harter, S., Low, S. M., & Whitesell, N. R. (2003). What have we learned from columbine: The impact of the self-system on suicidal and violent ideation among adolescents. Journal of School Violence, 2(3), 3–26.

Henrich, C. C., Brookmeyer, K. A., & Shahar, G. (2005). Weapon violence in adolescence: Parent and school connectedness as protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37(4), 306–312.

Henry, K. L., & Slater, M. D. (2007). The contextual effect of school attachment on young adolescents’ alcohol use. Journal of School Health, 77(2), 67–74.

Herrenkohl, T. I., Huang, B., Tajima, E. A., & Whitney, S. D. (2003). Examining the link between child abuse and youth violence: An analysis of mediating mechanisms. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(10), 1189–1208.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2007). Offline consequences of online victimization: School violence and delinquency. Journal of School Violence, 6(3), 89–112.

Hirschfield, P. J., & Gasper, J. (2011). The relationship between school engagement and delinquency in late childhood and early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(1), 3–22.

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of Delinquency. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Hirschi, T. (2004). Self-control and crime. In R. F. Baumeister & K. D. Vohs (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 537–552). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Iratzoqui, A. (2015). Strain and opportunity: A theory of repeat victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515615146.

Jenkins, P. H. (1997). School delinquency and the school social bond. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 34(3), 337–367.

Johnson, M. K., Crosnoe, R., & Thaden, L. L. (2006). Gendered patterns in adolescents' school attachment. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69(3), 284–295.

Juan, S. C., & Hemenway, D. (2017). From depression to youth school gun carrying in America: Social connectedness may help break the link. Cogent Social Sciences, 3(1), 1314877.

Kann, L. et al. (2016). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2015. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 65.

Kaufman, J. M. (2009). Gendered responses to serious strain: The argument for a general strain theory of deviance. Justice Quarterly, 26(3), 410–444.

Kennedy, D. M., Piehl, A. M., & Braga, A. A. (1996). Youth violence in Boston: Gun markets, serious youth offenders, and a use-reduction strategy. Law and Contemporary Problems, 59(1), 147–196.

Klein, J. (2005). Teaching her a lesson: Media misses boys’ rage relating to girls in school shootings. Crime, Media, Culture, 1(1), 90–97.

Leary, M. R., Kowalski, R. M., Smith, L., & Phillips, S. (2003). Teasing, rejection, and violence: Case studies of the school shootings. Aggressive Behavior, 29(3), 202–214.

Lester, L., Waters, S., & Cross, D. (2013). The relationship between school connectedness and mental health during the transition to secondary school: A path analysis. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 23(2), 157–171.

Lipsey, M. W., & Derzon, J. H. (1998). Predictors of violent and serious delinquency in adolescence and early adulthood: A synthesis of longitudinal research. In R. Loeber & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions (pp. 86–105). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Longshore, D., Chang, E., & Messina, N. (2005). Self-control and social bonds: A combined control perspective on juvenile offending. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 21(4), 419–437.

Lowry, R., Powell, K. E., Kann, L., Collins, J. L., & Kolbe, L. J. (1998). Weapon-carrying, physical fighting, and fight-related injury among US adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(2), 122–129.

May, D. C. (1999). Scared kids, unattached kids, or peer pressure: Why do students carry firearms to school? Youth & Society, 31(1), 100–127.

McNeely, C., & Falci, C. (2004). School connectedness and the transition into and out of health-risk behavior among adolescents: A comparison of social belonging and teacher support. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 284–292.

McNeely, C. A., Nonnemaker, J. M., & Blum, R. W. (2002). Promoting school connectedness: Evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Journal of School Health, 72(4), 138–146.

Melde, C., Esbensen, F. A., & Taylor, T. J. (2009). ‘May piece be with you’: A typological examination of the fear and victimization hypothesis of adolescent weapon carrying. Justice Quarterly, 26(2), 348–376.

Meloy, J. R., Hempel, A. G., Mohandie, K., Shiva, A. A., & Gray, B. T. (2001). Offender and offense characteristics of a nonrandom sample of adolescent mass murderers. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(6), 719–728.

Monahan, K. C., Oesterle, S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2010). Predictors and consequences of school connectedness. The Prevention Researcher, 17(3), 3–6.

Moore, M. H., Petrie, C. V., Bragaand, A. A., & McLaughlin, B. L. (2003). Deadly lessons: Understanding lethal school violence. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Muschert, G. W. (2007). Research in school shootings. Sociology Compass, 1(1), 60–80.

Mustard, D. B. (2003). Reexamining criminal behavior: The importance of omitted variable bias. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(1), 205–211.

Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2011). Traditional and nontraditional bullying among youth: A test of general strain theory. Youth Society, 43(2), 727–751.

Paternoster, R., & Pogarsky, G. (2009). Rational choice, agency and thoughtfully reflective decision making: The short and long-term consequences of making good choices. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 25(2), 103–127.

Payne, A. A. (2009). Girls, boys, and schools: Gender differences in the relationships between school-related factors and student deviance. Criminology, 47(4), 1167–1200.

Pearson, J., Muller, C., & Wilkinson, L. (2007). Adolescent same-sex attraction and academic outcomes: The role of school attachment and engagement. Social Problems, 54(4), 523–542.

Pickett, W., Craig, W., Harel, Y., Cunningham, J., Simpson, K., Molcho, M., et al. (2005). Cross-national study of fighting and weapon carrying as determinants of adolescent injury. Pediatrics, 116(6), e855–e863.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Radloff, L. S. (1991). The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 20(2), 149–166.

Resnick, M. D., Harris, L. J., & Blum, R. W. (1993). The impact of caring and connectedness on adolescent health and well-being. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 29(s1), S3–S9.

Resnick, M. D., Bearman, P. S., Blum, R. W., Bauman, K. E., Harris, K. M., Jones, J., et al. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on adolescent health. JAMA, 278(10), 823–832.

Resnick, M. D., Ireland, M., & Borowsky, I. (2004). Youth violence perpetration: What protects? What predicts? Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35(5), 424–4e1.

Romo, L. F., & Nadeem, E. (2007). School connectedness, mental health, and well-being of adolescent mothers. Theory into Practice, 46(2), 130–137.

Schubiner, H., Scott, R., & Tzelepis, A. (1993). Exposure to violence among inner-city youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 14(3), 214–219.

Shetgiri, R., Boots, D. P., Lin, H., & Cheng, T. L. (2016). Predictors of weapon-related behaviors among African American, Latino, and white youth. The Journal of Pediatrics, 171, 277–282.

Shochet, I. M., Dadds, M. R., Ham, D., & Montague, R. (2006). School connectedness is an underemphasized parameter in adolescent mental health: Results of a community prediction study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 35(2), 170–179.

Simon, T. R., Crosby, A. E., & Dahlberg, L. L. (1999). Students who carry weapons to high school: Comparison with other weapon-carriers. Journal of Adolescent Health, 24(5), 340–348.

Steuber, T. L., & Danner, F. (2006). Adolescent smoking and depression: Which comes first? Addictive Behaviors, 31(1), 133–136.

Udry, J. R. (2003). The National Longitudinal Study of adolescent health (add health). Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Watts, S. J. (2017). The link between child abuse and neglect and delinquency: Examining the mediating role of social bonds. Victims & Offenders, 12(5), 700–717.

Watts, S. J., & McNulty, T. L. (2013). Childhood abuse and criminal behavior: Testing a general strain theory model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(15), 3023–3040.

Watts, S. J., & McNulty, T. L. (2015). Delinquent peers and offending: Integrating social learning and biosocial theory. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 13(2), 190–206.

Webber, J. A. (2003). Failure to hold: The politics of school violence. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Webster, D. W., Gainer, P. S., & Champion, H. R. (1993). Weapon carrying among inner-city junior high school students: Defensive behavior vs aggressive delinquency. American Journal of Public Health, 83(11), 1604–1608.

Wilcox, P., May, D. C., & Roberts, S. D. (2006). Student weapon possession and the “fear and victimization hypothesis”: Unraveling the temporal order. Justice Quarterly, 23(4), 502–529.

Wilson, D. (2004). The interface of school climate and school connectedness and relationships with aggression and victimization. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 293–299.

Winfree Jr, L. T., & Abadinsky, H. (2009). Understanding Crime: Essentials of Criminological Theory (Third Edition ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage.

Zhang, L., & Messner, S. F. (1996). School attachment and official delinquency status in the People's Republic of China. Sociological Forum, 11(2), 285–303.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Items for scaled measures

Appendix: Items for scaled measures

Depression Wave I

How often was each of the following things true in the past week?

-

1.

You were bothered by things that usually don’t bother you.

-

2.

You didn’t feel like eating, your appetite was poor.

-

3.

You felt that you could not shake off the blues, even with help from your family and your friends.

-

4.

You felt you were just as good as other people. (reverse coded)

-

5.

You felt depressed.

-

6.

You felt that you were too tired to do things.

-

7.

You felt hopeful about the future. (reverse coded)

-

8.

You thought your life had been a failure.

-

9.

You felt fearful.

-

10.

You were happy. (reverse coded)

-

11.

You talked less than usual.

-

12.

You felt lonely.

-

13.

People were unfriendly to you.

-

14.

You enjoyed life. (reverse coded)

-

15.

You felt sad.

-

16.

You felt that people disliked you.

-

17.

It was hard to get started doing things.

-

18.

You felt life was not worth living.

School Attachment Wave I

During the current/most recent school year, how often have you had trouble…

-

1.

getting along with your teachers?

-

2.

getting along with other students?

-

3.

How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

-

4.

You feel close to people at your school.

-

5.

You feel like a part of your school.

-

6.

Students at your school are prejudiced.

-

7.

You are happy to be at your school.

-

8.

The teachers at your school treat students fairly.

-

9.

You feel safe in your school.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Watts, S.J., Province, K. & Toohy, K. The Kids Aren’t Alright: School Attachment, Depressive Symptoms, and Gun Carrying at School. Am J Crim Just 44, 146–165 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-018-9438-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-018-9438-6