Abstract

The crime figures among Antilleans (people from islands in the Caribbean Sea) residing in the European country of the Netherlands remain high for offenders in their twenties and thirties, unlike other major ethnic groups residing in the Netherlands. The aim of this study is to get a better insight into the backgrounds of the deviances in the shape of the age-crime curve for this ethnic group. The research comprises a quantitative analysis of data regarding people who are registered as an offender in the Netherlands. This study has found indications that the high level of broken families might be related to comparatively high rate of offenders among adult Antillean men up to approximately 45 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

People often wrongly use the term Holland when they want to refer to the Netherlands. Holland only includes two of the 12 provinces of the Netherlands, North and South Holland. The English word which is used to refer to the people, the language, and anything pertaining to the Netherlands is Dutch. This adjective is derived from the regional languages that were spoken in the area, which were commonly known as ‘Diets’.

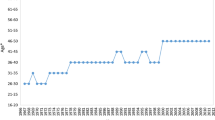

Source: Statistics Netherlands. See the data section for information on how the different origin groups are differentiated.

On January 1, 1986, Aruba seceded from the Netherlands Antilles. On that date, it obtained the desired ‘status aparte’ (the status of a fully autonomous state under the Dutch crown), which delivered it from what it experienced to be the controlling position of Curaçao. On October 10, 2010, the Netherlands Antilles ceased to exist. Beside Aruba, Curaçao and St. Maarten also became sovereign states within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Bonaire, St. Eustatius and Saba once again fell under direct Dutch rule. Thus, the Kingdom of the Netherlands nowadays consists of four states: the Netherlands, Aruba, Curaçao, and St. Maarten.

Here and in the rest of this study, we use the term ‘Antilleans’ to designate people who originate from either the Netherlands Antilles or Aruba.

Here, we speak of ‘broken families’ according to Dutch standards. Within the Antillean community, families consisting of a single mother with children are quite common. These families are often matrifocal. If we were to look at families from an Antillean perspective, however, we would probably speak of ‘broken families’ with regard to cases in which children would no longer live with their mother, regardless of their father’s whereabouts.

Still, we want to point out a notable fact here that emerges from this study. The overrepresentation in the crime statistics of Antilleans in their early teens also turns out to be very high. This might be related to the frequent incidence of single-parent families in the Antillean community. The relatively low overrepresentation of Antillean adolescents may be connected to the only limited existence of a maturity gap (for more information see Moffitt, 1993) for this origin group, which may also be caused by the frequent incidence of single-parent families. Because of this, many Antillean teenagers enter socio-economic domains at a relatively early age, while individuals from other origin groups who are active in these domains have almost exclusively turned 20 quite some time ago.

The former Netherlands Antilles are situated in the Caribbean, relatively close to the cocaine producing areas in South America. In addition, the island of Curaçao has become the site of an important seaport due to its natural deep water harbour and many excellent natural landing stages for smaller boats. These two factors cause, together with the fact that citizens of the former Netherlands Antilles have Dutch passports and can therefore travel without restriction between the European and the Caribbean part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, a situation in which the use of and trade in cocaine became more or less socially acceptable in the lower strata of the (transnational) Antillian community.

In this study, we count this English-speaking country in South America as one of the Carribean countries.

For this part of the world, there are few (age-specific) crime statistics relating to a reasonably sizeable population, anyhow. In a similar way, for example, an attempt to collect for comparison age-specific crime rates of southern and north-eastern Brazilian states with a low and a high percentage of Afro-Brazilians, respectively, also remained fruitless.

Actually, it is not completely appropriate to speak about ‘native Dutch’ here, as a person whose parents are both born in the Netherlands, but is born abroad him- or herself is also considered to this category. The term ‘autochthonous people’ is used in official publications of Statistics Netherlands and in the most other Dutch publications on migration and integration issues to indicate aforementioned persons. The term ‘allochthonous people’ is used in these publications to indicate the persons who have at least one parent who is born abroad.

Indonesia counts as a Western country, since many of the people who are Indonesian immigrants according to the SN’s definition, are (descendants of) Dutch colonists or Indo-Europeans who were born in the former colony of the Dutch East Indies. Japan is counted as a Western country because of its high standard of living.

SN assembles the SSB from a large number of registers and surveys that contain privacy-sensitive data. For this reason, SN pays a great deal of attention to securing these data.

Another possibility would be to express crime rates in the number of registered offenses per capita (see for instance Huls & Jennisssen, 2008, p. 197).

The age-crime curves represented in figure 3 are based on moving averages of three ages. This means that the values of the age-specific crime rates of which the curve consists are the average for every age of the crime rates for the ages in question as well as for the two surrounding ages. Thus, the value of age 13, for example, is the average of the values for the ages of 12, 13 and 14, while the value for age 14 is the average of the values for the ages of 13, 14 and 15, et cetera. The values of the youngest and oldest age groups, in this case those of ages 12 and 60, respectively, have been excluded.

Rotterdam is the second largest city of the Netherlands, with approximately 600,000 inhabitants. Of all the Dutch municipalities, Rotterdam relatively houses most people with a non-Western background. It is also the city with the largest Antillean population, namely approximately 20,000.

According to van San et al. (2007), this percentage is probably an underestimation, because single mothers who are living in with their children or who are staying in shelters for battered women have not been included.

References

Arts, C. H., & Hoogteijling, E. M. J. (2002). Het Sociaal Statistisch Bestand 1998 en 1999. Sociaal-economische Maandstatistiek, 2002(12), 13–21.

Beriss, D. (2004). Black skins, French voices: Caribbean ethnicity and activism in urban France. Boulder (CO): Westview Press.

Blokland, A., & Nieuwbeerta, P. (2005). The effects of life circumstances on longitudinal trajectories of offending. Criminology, 43(4), 1203–1240.

Blom, M., Oudhof, J., Bijl, R. V., & Bakker, B. F. M. (2005). Verdacht van criminaliteit: allochtonen en autochtonen nader bekeken. Den Haag: WODC.

Borghans, L., & Ter Weel, B. (2003). Criminaliteit en etniciteit. Economisch Statistische Berichten, 88(4419), 548–550.

Braithwaite, F. (1996). Some aspects of sentencing in the criminal justice system of Barbados. Caribbean Quarterly, 42(2/3), 113–130.

Cain, M. (2000). Orientalism, occidentalism and the sociology of crime. British Journal of Criminology, 40(2), 239–260.

CRE. (2007). Ethnic minorities in Great Britain. Londen: Commission for Racial Equality.

Dagevos, J., & Gijsberts, M. (2007). Jaarrapport integratie 2007. Den Haag: SCP.

De Maillard, J., & Roché, S. (2004). Crime and justice in France: time trends, policies and political debate. European Journal of Criminology, 1(1), 111–151.

Faber, W., Mostert, S., Nelen, J. M., Van Nunen, A. A. A., & La Roi, C. (2007). Baselinestudy criminaliteit en rechtshandhaving Curaçao en Bonaire. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit.

Furstenberg, F. F. (2007). The making of the black family: race and class in qualitative studies in the twentieth century. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 429–448.

Garssen, J., & Nicolaas, H. (2006). Recente trends in de vruchtbaarheid van niet-westerse allochtone vrouwen. Bevolkingstrends, 54(1), 15–31.

Gendreau, P., Little, T., & Goggin, C. (1996). A meta-analysis of the predictors of adult offender recidivism: what works! Criminology, 34(4), 575–607.

Glaser, D., & Rice, K. (1959). Crime, age, and employment. American Sociological Review, 24(5), 679–686.

Gould, E. D., Weinberg, B. A., & Mustard, D. B. (2002). Crime rates and local labor market opportunities in the United States. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(1), 45–61.

Gove, W. (1985). The effect of age and gender on deviant behaviour: a biopsychosocial perspective. In A. Rossi (Ed.), Gender and the life course (pp. 115–144). Hawthorne: Aldine.

Harriott, A. (1996). The changing social organization of crime and criminals in Jamaica. Caribbean Quaterly, 42(2/3), 61–81.

Haut, F., & Raufer, X. (2007). Violences urbaines en France: La guerre de bientôt 30 ans… de retard. Parijs: Université Panthéon-Assas.

Hirschi, T., & Gottfredson, M. (1983). Age and the explanation of crime. American Journal of Sociology, 89(3), 552–584.

Huls, F., & Jennisssen, R. (2008). Veiligheid en criminaliteit. In K. Oudhof, R. Van der Vliet, & B. Hermans (Eds.), Jaarrapport integratie 2008 (pp. 177–200). Den Haag: CBS.

Jennissen, R. P. W. (2009). Criminaliteit, leeftijd en etniciteit: over de afwijkende leeftijdsspecifieke criminaliteitscijfers van in Nederland verblijvende Antillianen en Marokkanen. Den Haag: WODC.

Jennissen, R. P. W., & Blom, M. (2007). Allochtone en autochtone verdachten van verschillende delicttypen nader bekeken. Den Haag: WODC.

Jennissen, R., Blom, M., & Oosterwaal, A. (2009). Geregistreerde criminaliteit als indicator van de integratie van niet-westerse allochtonen. Mens & Maatschappij, 84(2), 207–233.

Jones, H. (1981). Crime, race and culture: a study in a developing country. Chichester: Wiley.

Kanazawa, S., & Still, M. C. (2000). Why men commit crimes (and why they desist). Sociological Theory, 18(3), 434–447.

Keij, I. (2000). Hoe doet het CBS dat nou? Standaarddefinitie allochtonen. Index: Feiten en Cijfers over onze Samenleving, 10, 24–25.

Korf, D. J., Bookelman, G. W., & de Haan, T. (2001). Diversiteit in criminaliteit: Allochtone arrestanten in de Amsterdamse politiestatistiek. Tijdschrift voor Criminologie, 43(3), 230–259.

Kromhout, M., & Van San, M. (2003). Schimmige werelden: Nieuwe etnische groepen en jeugdcriminaliteit. Den Haag: Boom Juridische uitgevers.

Meyer, S. (2007). Sozialkapital und Delinquenz: Eine empirische Untersuchung für Deutschland. Darmstadt: Technische Universität Darmstadt.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100(4), 674–701.

van Niekerk, M. (2000). De krekel en de mier: Fabels en feiten over maatschappelijke stijging van creoolse en hindoestaanse Surinamers in Nederland. Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis.

Oostindie, G. (2008). Slavernij, canon en trauma: Debatten en dilemma’s. Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis, 121(1), 4–21.

Oostindie, G. (2010). Postkoloniaal Nederland: Vijfenzestig jaar vergeten, herdenken, verdringen. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Bert Bakker.

Safa, H. I. (2005a). The matrifocal family and patriarchal ideology in Cuba and the Caribbean. Journal of Latin American Anthropology, 10(2), 314–338.

Safa, H. I. (2005b). Challenging mestizaje: a gender perspective on indigenous and afrodescendant movements in Latin America. Critique of Anthropology, 25(3), 307–330.

Sampson, R. J. (1987). Urban black violence: the effect of male joblessness and family disruption. American Journal of Sociology, 93(2), 348–382.

van San, M., De Boom, J., & Van Wijk, A. (2007). Verslaafd aan een flitsende levensstijl: Criminaliteit van Antilliaanse Rotterdammers. Rotterdam: RISBO.

Smith, D. J. (1997). Ethnic origins, crime and criminal justice in England and Wales. Crime and Justice, 21, 101–182.

Soothill, K., Ackerley, E., & Francis, B. (2004). Profiles of crime recruitment: changing patterns over time. British Journal of Criminology, 44(3), 401–418.

Steffensmeier, D. J., & Allen, E. A. (1995). Criminal behaviour: gender and age. In J. F. Sheley (Ed.), Criminology: a contemporary handbook (pp. 83–113). Belmont: Wadsworth.

Steffensmeier, D. J., Allen, E. A., Harer, M. D., & Streifel, C. (1989). Age and the distribution of crime. American Journal of Sociology, 94(4), 803–831.

Taskforce Antilliaanse Nederlanders. (2008). Antilliaanse probleemgroepen in Nederland: Een oplosbaar maatschappelijk vraagstuk. Den Haag: Taskforce Antilliaanse Nederlanders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The author wishes to thank Elise Beenakkers, Arjan Blokland, Frank Bovenkerk, Inger Bregman, Dick Brons, Mariska Kromhout, Frans Leeuw, Djamila Schans, Monika Smit, Ellen Uiters, Helga de Valk, Gijs Weijters and two anonymous reviewers for their help.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jennissen, R. On the deviant age-crime curve of Afro-Caribbean populations: The case of Antilleans living in the Netherlands. Am J Crim Just 39, 571–594 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-013-9234-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-013-9234-2