Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to use criminological theories to explain chronic drunk driving. There is little criminological research explaining recidivist drunk driving with criminological theories. Instead, most researchers posit that repeat drunk driving is explained as a byproduct of substance abuse. Although substance abuse is likely correlated to chronic drunk driving, theoretical explanations need to go further to understand a broader set of social and psychological predictors. Factor analysis and linear regression techniques are used to estimate the relationship between items from two assessment instruments with a number of drunken driving offenses. The sample consists of nearly 3,500 individuals on probation and parole in a Southwestern state. The findings support our contention that criminological frameworks are helpful to understand chronic DUI. We found significant results for volatility, antisocial friends, teenage deviance, and negative views of the law, while controlling for age, gender, marital status, and race. DUIs are a serious problem for the criminal justice system and understanding the individual level correlates of repetitive DUI is crucial for policy development. Further, chronic DUI offers criminologists an opportunity to determine the ability of criminological theories to explain this type of behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We refer to drunk driving as DUI throughout this article. No doubt, different states and jurisdictions refer to this crime in various ways such as impaired driving, driving while drunk, driving while intoxicated, and other names. DUI is mean as a synonym of these other terms to identify individuals arrested for driving after consuming illegal amounts of alcohol.

Probation and parole are administered through the Department of Corrections as a unified system in Oklahoma.

The data were extracted and delivered to the researchers in December 2009, and they are a snapshot of the drunken driving population on a given day in 2009. This study is retrospective and it lacks duration or longitudinal data, so we are unable to study timing or occurrence of new DUIs. Instead, our analysis focuses on the total number of DUI arrests.

Risk assessment total scores can range from 1–54.

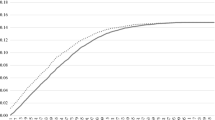

This discussion relies on several sources, but mostly works from Long and Freese’s (2006) discussion of Poisson models in chapter 8. Those interested in a more in thorough treatment of Poisson models and count data are referred to their book as well as Cameron and Trivedi (1998). We follow Long and Freese’s equation symbol of the estimated rate of a count, μ, as opposed to the symbol more commonly used in criminological texts, λ (see Lattimore et al., 2004; Nagin & Land, 1993; Osgood, 2000), but the equations are identical, merely the symbol is different.

The observation is still Poisson when using a negative binomial regression model, and each will tend to give close point estimates, but the Poisson model tends to deflate standard errors causing inflated z-tests and incorrect p-values (Osgood, 2000). Thus, the Poisson regression model could lead to incorrect hypothesis testing (Cameron & Trivedi, 1998). We estimated and compared models using a Poisson and negative binomial regression and found this to be true, with similar estimates and widely varying standard errors (analyses available upon request).

Initial comparisons between the Poisson and negative binomial regression models produced consistent significant chi-square tests confirming overdispersion (p < .000).

We were concerned with the high presence of 0 in our dependent variable, and investigated zero-inflated negative binomial regression models. The zero-inflated models fit models for the negative binomial as well as fit those not experiencing the outcome (no prior DUI arrests) with a unique set of covariates simultaneously (Lambert, 1992). Long and Freese (2006) developed the countfit Stata procedure that compares these models, and the fit tests did not show that the zero-inflated negative binomial regression model was a better fit for the data (Voung test, p = .283).

References

Agnew, R. (2006). Pressured into crime: An overview of general strain theory. Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

Agnew, R. (1992). Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology, 30(1), 47–87.

Akers, R., & Sellers, C. (2009). Criminological theories: Introduction, evaluation, and application (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Andrews, D., & Bonta, J. (2004). The psychology of criminal conduct (3rd ed.). Cincinnati, OH: Anderson Publishing.

Berk, R. (2011). An introduction to ensemble methods for data analysis. Department of Statistics Papers, Department of Statistics, UCLA, UC Los Angeles. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/54d6g9gf.

Bouffard, J., & Rice, S. (2011). The influence of the social bond on self-control at the moment of decision: testing Hirschi’s redefinition of self-control. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 36, 138–157.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (1998). Regression analysis of count data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, L., & Vila, B. (1996). Self-control and social-control: an exposition of the Gottfredson-Hirschiisampson-Laubdebate. Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention, 5, 125–150.

DeMichele, M., & Payne, B. (2012). Predicting repeat DWI: chronic offending, risk assessment, and community supervision. Lexington, KY: American Probation and Parole Association. https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/Abstract.aspx?id=260552. Accessed 15 July 2013.

Freeman, J., & Watson, B. (2006). An application of Stafford and Warr’s reconceptualisation of deterrence to a group of recidivist drink driver. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 38, 462–471.

Gardner, W., Mulvey, E. P., & Shaw, E. C. (1995). Regression analyses of counts and rates: Poisson, overdispersed Poisson, and negative binomial models. Psychological Bulletin, 118, 392–404.

Gottfredson, M., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Lambert, D. (1992). Zero-inflated Poisson regression, with an application to defects in manufacturing. Technometrics, 34(1), 1–14.

Lattimore, P., MacDonald, J., Piquero, A., Linster, R., & Visher, C. (2004). Studying the characteristics of arrest frequency among paroled youthful offenders. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 41, 37–57.

Laub, J., & Sampson, R. (2005). Shared beginnings: Delinquent boys to age 70. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lenton, S., Fetherston, J., & Cercarelli, R. (2010). Recidivist drink drivers’ self-reported reasons for driving whilst unlicensed—a qualitative analysis. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 42, 637–644.

Long, S., & Freese, J. (2006). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata (2nd ed.). College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Lowenkamp, C., & Latessa, E. (2004). Understanding the risk principle: how and why correctional interventions can harm low-risk offenders. Topics in community corrections. Washington, DC: National Institute of Corrections.

Maltz, M. D. (1994). Operations research in studying crime and justice: Its history and accomplishments. In S. M. Pollock, M. H. Rothkopf, & A. Barnett (Eds.), Operations research and the public sector, Volume 6 of Handbooks in operations research and management science (pp. 200–262). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Mazerolle, P., & Piquero, A. (1998). Linking exposure to strain with anger: an investigation of deviant adaptations. Journal of Criminal Justice, 26, 195–211.

Monahan, J., Steadman, H., Silver, E., Appelbaum, P., Robbins, P., Mulvey, E., et al. (2001). Rethinking risk assessment: The MacArthur study of mental disorder and violence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nagin, D., & Land, K. (1993). Age, criminal careers, and population heterogeneity: specification and estimation of a nonparametric, mixed Poisson model. Criminology, 31, 327–362.

Osgood, D. W. (2000). Poisson-based regression analysis of aggregate crime rates. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 16, 21–43.

Rauch, W., Zador, P., Ahlin, E., Howard, J., Frissell, K., & Duncan, G. (2010). Risk of alcohol-impaired driving recidivism among first offenders and multiple offenders. American Journal of Public Health, 100(5), 919–924.

Royal, D. (2003). National survey of drinking and driving attitudes and behavior: 2001, Volume I: Summary report (DOT HS 809 549). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation.

Silver, E., & Chow-Martin, L. (2001). A multiple models approach to assessing recidivism risk: Implications for judicial decision making. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 29, 538–568.

Taxman, F., & Piquero, A. (1998). On preventing drunk driving recidivism: an examination of rehabilitation and punishment approaches. Journal of Criminal Justice, 26, 129–144.

Wanberg, K., Milkman, H., & Timken, D. (2005). Criminal conduct and substance abuse treatment: Strategies for self improvement and change: Pathways to responsible living, participant’s handbook. New York: Sage Publishing.

Wanberg, K., Timken, D., Milkman, H. (2010). Driving with care: Education and treatment: Education and treatment of the underage impaired driving offender, strategies for responsible living and change (Adjunct Provider’s Guide). New York: Sage Publishing.

Wanberg, K., & Milkman, H. (2010). Provider’s handbook for assessing criminal conduct and substance abuse clients: Progress and change evaluation (PACE) monitor. New York: Sage.

Winfree, L. T., Jr., & Giever, D. (2000). On classifying driving-while-intoxicated offenders: the experiences of a citywide D.W.I. drug court. Journal of Criminal Justice, 28(1), 13–21.

Winfree, L. T., Giever, D. M., Maupin, J. R., & Mays, G. L. (2007). Drunk driving and the prediction of analogous behavior: a longitudinal test of social learning and self-control theories. Victims and Offenders, 2(4), 327–349.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Penn State University’s Justice Center for Research for supporting the development of this paper, and we thank Doris MacKenzie for helpful comments throughout. Additionally, we thank the American Probation and Parole Association for their ongoing commitment to facilitate this research and advance research in community corrections. None of these individuals or organizations are responsible for any of the conclusions or errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DeMichele, M., Lowe, N.C. & Payne, B.K. A Criminological Approach to Explain Chronic Drunk Driving. Am J Crim Just 39, 292–314 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-013-9216-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-013-9216-4