Abstract

This research note explores the rationale for consistently submitting scholarly manuscripts to and publishing in American Journal of Criminal Justice. By means of structured interviews with nine of the most frequently published authors throughout the history of the journal, this research identifies that AJCJ’s manuscript review process and its readership are the most common themes regarding motivations for consistently selecting the journal. Specifically, data reveals that these authors believe that timely responses to submissions, high-quality feedback, helpful editors, increased audience exposure, and received feedback from readers make AJCJ an attractive and viable outlet for their research articles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent years have seen criminology and criminal justice (CCJ) scholars focus attention on not only the theoretical and topical foci of their discipline, but also on the ways in which they produce their scholarship and contribute to the accumulation of knowledge about crime and justice. In a reflexive manner, scholars have turned inward on the discipline, examining research productivity rates of scholars and identifying highly productive scholars (Rice, Cohn, & Farrington, 2005; Rice, Terry, Miller, & Ackerman, 2007; Shutt & Barnes, 2008; Worley, 2011) and major grant funding recipients (Mustaine & Tewksbury, 2009). Major and productive works in the discipline (Reisig, 2001; Vito & Tewksbury, 2008) and studies that are most commonly included in texts and educational materials (Wright, 2002; Wright, Malia, & Johnson, 1999; Wright & Miller, 1999; Wright & Sheridan, 1997) have also been highlighted. This inward look has spawned special issues of highly regarded journals in the discipline (cf. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, volume 22, no. 1, 2011). Accompanying this reflexive examination of the discipline, several attempts by scholars to identify publication outlets that are the most influential on the discipline (Jennings, Higgins, & Khey, 2009; Sorenson, 2009) and those considered by scholars as the most important (Sorenson, Snell, & Rodriguez, 2006) have been undertaken. Others have focused on trends in methodological orientations (Copes, Brown, & Tewksbury, 2011; DiChristina, 1997; Kleck, Tark, & Bellows, 2006; Tewksbury, Dabney, & Copes, 2010; Tewksbury, DeMichele, & Miller, 2005) and topical foci for articles published both in the discipline as a whole and in specific journals (Tewksbury & Mustaine, 2001).

However, while CCJ scholars have focused their attention on what is produced and where and by whom in the discipline, little attention has been devoted to understanding the process by which research is brought to publication. Although there are a few autobiographical reflections on individual careers (Pogrebin, 2010), assessments of the manuscript review process (Mustaine & Tewksbury, 2008; Tewksbury & Mustaine, in press), and evaluations of the number and composition of author teams for published articles (Tewksbury & Mustaine, 2011), there remains no systematic examination of how and why CCJ scholars seek to publish their work in particular outlets. Surely considerations of prestige (as measured by characteristics such as a journal’s impact factor or informal ranking in the eyes of one’s peers) are important, as may be placing one’s work in outlets where it is most likely to be read by one’s target audience. However, such attitudes and beliefs are based largely on anecdotal evidence and lack systematically gathered support.

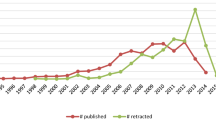

The purpose of the present paper is to examine how and why the authors who have most frequently published in the American Journal of Criminal Justice (AJCJ) make the decision to place their work in this journal. The AJCJ, which has recently been examined for topical content and had its growth and development charted for its more than 35-year history (Miller, Tewksbury, & Worley, 2012), is the official publication of the Southern Criminal Justice Association, one of the five regional criminal justice scholarly associations in the United States. The AJCJ is the oldest of the regionally sponsored/published journals, and, at least anecdotally, it is the most widely recognized and highest-ranked by discipline scholars. Based on this foundation, the present study explores the reasoning for consistent publication in the journal among nine of the most frequently published authors throughout the history of the journal, as identified by Miller et al. (2012).

Methodology

All data for the present analysis come from structured interviews conducted with nine individuals identified as the most frequently published authors in the American Journal of Criminal Justice. Based on Miller et al.’s (2012) review of the first 35 volumes of the journal, twelve authors were identified as having published five or more articles in the journal. The individuals who distinguished themselves from all other authors as the “high rate publishers” were: Richard Tewksbury (12 publications in AJCJ), Eric Lambert (10), Gennaro Vito (8), Elizabeth Mustaine (7), G. Larry Mays (7), George Higgins (6), David Giacopassi (6), Francis Cullen (6), Nancy Hogan (6), J. Mitchell Miller (5), Reed Adams (5) and Matt DeLisi (5). The above scholars published articles which appeared in the American Journal of Criminal Justice between 1975 through the first issue of 2010. For the purposes of this paper, only articles that were published within this timeframe were counted toward a respondent’s total number of publications in the AJCJ.

Once identified as the high rate publishers in AJCJ, each of the above authors (with the exception of Richard Tewksbury), was invited via e-mail to participate in a structured, telephone interview. Nine of these authors agreed, and interviews were completed within 2 weeks of initial correspondence. All interviews were conducted by the same interviewer and followed a structured interview guide.

Each interview was transcribed verbatim. Data were coded following principles of analytic induction in multiple readings (Charmaz, 1983, 2006). Each reading of the transcripts focused on a narrow range of issues and conceptual categories concerning authors’ rationale for consistently selecting the AJCJ as an outlet for publication. As these high rate publishers have been previously identified (Miller et al., 2012), all quotes presented in this paper are attributed to their speakers using the authors’ real names.

Findings

All of the interviewed authors believed that the American Journal of Criminal Justice was an excellent outlet to which they could submit their scholarly research. Two of the respondents, George Higgins and Gennaro Vito, had also served as Editor of the AJCJ. In fact, Vito, who served as Editor of AJCJ from 1987 to 1991, expressed a particularly strong fondness for AJCJ. He made the following statement:

I’ve seen the journal come up from rather modest beginnings to the point where it now has a publisher full-time and will go quarterly. In the beginning, it was two issues and we all worked hard to keep it alive. And now it’s really kind of made the big time.

While most of the respondents expressed their admiration for the AJCJ, interview data yielded two primary sets of findings that explained motivations for consistently selecting the journal for their work. These focused on the journal’s manuscript review process and its readership.

The manuscript review process was the most commonly reported motivation for repeatedly selecting the AJCJ as an outlet for publishing scholarly research. When compared to other scholarly journals, most authors believed the quality of the manuscript review process at AJCJ was exemplary. According to Francis Cullen, author of six articles published between 1989 and 2005 in the AJCJ, “The quality of the review process makes a big difference when people submit their work.” Specifically, these authors believed that timely responses to submissions, high-quality feedback, and helpful editors made AJCJ both an attractive and viable outlet for their research articles. For example, Elizabeth Mustaine, a recent Past President of the Southern Criminal Justice Association, explained, “The turnaround time is good. It doesn’t take very long to get word back about the status of your manuscript.”

A near-universal factor related to the manuscript review process that positively influenced authors’ perceptions of AJCJ as an attractive outlet for their scholarly work concerned timely responses to their submissions. Nearly all of the authors believed that scholarly journals that provided a response on the status of their submission within a reasonable time period were the most attractive outlets. As Francis Cullen elaborated, “If I sent something to a journal, and I don’t hear anything for 8 months, then I would be unlikely to go back to that journal.” Among these authors, the AJCJ was regarded as consistently providing a decision about a manuscript within a reasonable period of time. Eric Lambert, author of 10 articles published between 1999 and 2010 in the AJCJ, suggested that “within about 90 to 100 days, [the AJCJ] will have something back to you or sooner, and you can’t say that about a lot of journals.” It was clear that these authors appreciated reasonable turnaround from journals in regards to their submissions, and AJCJ was seen as effectively providing this turnaround.

Another common theme associated with the manuscript review process that positively influenced authors’ perceptions of AJCJ as an attractive outlet for their scholarly work focused on the quality of feedback that was provided. Most authors articulated that high-quality feedback was consistently made available to scholars who submitted their work to AJCJ. They believed that the journal actively obtained qualified reviewers that were interested in reading submitted manuscripts and willing to provide constructive criticism. Eric Lambert explained this when he said, “This journal selects good reviewers that actually provide you with good reviews to help you improve your paper.” Others felt that the AJCJ’s staff members consistently attempted to assist in improving submitted manuscripts. “The editorial board,” stated Nancy Hogan, “was always very helpful with their comments.” Upon submitting their work to the AJCJ, authors reported being highly confident that they would receive meaningful comments that would enhance their manuscript. This certainty motivated them to continue selecting AJCJ for their research articles.

In addition, the presence of helpful editors throughout the AJCJ’s history was expressed as a factor that was influential in many authors’ repeated decisions to submit manuscripts to the journal. Like most of these authors, Eric Lambert recalled, “The AJCJ has always had excellent editors.” Unlike those of other journals, however, editors of the AJCJ were often seen as teachers, guiding authors through the publishing process. Numerous authors described these editors as gregarious individuals providing assistance in manuscript preparation and offering critical advice about improving manuscripts. A few authors also mentioned certain editors throughout the history of the AJCJ who facilitated positive submission experiences. For instance, both Matt DeLisi and Eric Lambert recalled that Bill Doerner was a “helpful” editor. “I liked how Doerner worked with authors and encouraged us,” stated Matt DeLisi, “and so I kept going back to the journal.” Without a doubt, many of these authors believed that the editors of AJCJ were beneficial to their early publishing experiences, and this consequently motivated them to consistently publish in the journal.

The second commonly reported motivation for repeatedly selecting AJCJ as an outlet for publishing scholarly research concerned the journal’s readership. Most authors stated a preference for scholarly journals that carried a large readership, and AJCJ was recognized among these authors as having a sizable number of readers, which helped to promote frequent submissions to the journal. Specifically, as it relates to a large readership, these authors believed that increased exposure and received feedback from readers made AJCJ both an attractive and viable outlet for their research articles.

A near-universal factor related to large readership that positively influenced authors’ perceptions of AJCJ as an attractive outlet for their scholarly work concerned increased exposure to their research. Many authors believed that in spite of writing a valuable research article, where the document was published was pertinent to it being seen and utilized. “My first preference in a journal,” stated Francis Cullen, “would be one that gives everybody in the field a chance to look at what I’ve written.” Among these authors, AJCJ was recognized as a scholarly journal that allowed such significant exposure. As stated simply by George Higgins, “I know it’s one that people will read.”

Most authors reported that they believed articles published in AJCJ would be viewed by a large readership because of its relationship to the Southern Criminal Justice Association. These authors acknowledged that each member of the Association would receive a hard copy edition of the AJCJ, which guaranteed a considerably large audience. The fact that the AJCJ was delivered to members of the Southern Criminal Justice Association was often a motivation for publishing in it. “That’s a big factor with the AJCJ, because the journal goes to all the members of the Southern Criminal Justice Association, which therefore makes it ensured that a certain number of people are going to have access to your work,” stated Francis Cullen. These authors felt that AJCJ’s connection to the regional criminal justice organization allowed increased visibility and made it more enticing.

After publishing in the AJCJ, a significant minority of authors reported receiving feedback from readers about their published studies. In the words of Nancy Hogan, “I’ve got several e-mails from people that either asked questions or wanted a follow-up.” Such feedback was often explained as an inevitable result of the substantial readership of the journal, and it was cited as a driving force behind continuing to publish in AJCJ. J. Mitchell Miller, another recent Past President of the Southern Criminal Justice Association, conveyed a similar sentiment toward the journal and also provided a vision of how the AJCJ could continue on its path toward success. Miller expressed himself in the following way:

A really good model to follow and aspiration for the American Journal of Criminal Justice would be to look to the history and success of Social Forces. Social Forces is the sociological counterpart to the American Journal. It’s the official publication of the Southern Sociological Society. And we’re the regional equivalent in criminal justice, but whereas the American Journal has remained sort of a regional level in reputation and status, Social Forces, even though it’s owned by the regional association, is considered a tier one journal. And I think that would certainly be something wonderful that could happen to the American Journal is that it could continue to improve and certainly the example of Social Forces shows that substantial improvement and this prestige realization is possible for a regional journal.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to explore the rationale for consistently submitting scholarly manuscripts to and publishing in American Journal of Criminal Justice. By means of structured interviews with nine of the most frequently published authors throughout the history of the journal, this research identified that AJCJ’s manuscript review process and its readership were the most common themes regarding motivations for consistently selecting the journal for their work. Specifically, data revealed that these authors believed that timely responses to submissions, high-quality feedback, helpful editors, increased audience exposure, and received feedback from readers made AJCJ an attractive and viable outlet for their research articles.

As the AJCJ looks toward the future, it should continue to provide authors with an efficient and dynamic manuscript review process, in order to encourage more and subsequent submissions that keep the journal competitive and inform our existing criminal justice knowledge base. For the same reasons, AJCJ should also maintain its ability to provide authors with a large readership. Ultimately, these efforts will allow AJCJ to persist in the discipline as an attractive outlet for cutting-edge criminal justice research from the leaders in our field.

References

Charmaz, K. (1983). The grounded theory method: An explication and interpretation. In R. Emerson (Ed.), Contemporary field research (pp. 109–126). Boston: Little and Brown.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

Copes, H., Brown, A., & Tewksbury, R. (2011). A content analysis of ethnographic research published in top criminology and criminal justice journals from 2000 to 2009. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 22(3), 341–359.

DiChristina, B. (1997). The quantitative emphasis in criminal justice education. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 8(2), 181–199.

Jennings, W. G., Higgins, G. E., & Khey, D. (2009). Exploring the stability and variability of impact factors and associated rankings in criminology and criminal justice journals, 1998–2007. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 20(2), 157–172.

Kleck, G., Tark, J., & Bellows, J. J. (2006). What methods are most frequently used in research in criminology and criminal justice? Journal of Criminal Justice, 34(2), 147–152.

Miller, A., Tewksbury, R., & Worley, R. M. (2012). The role and place of American Journal of Criminal Justice in the discipline. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 37(1), 126–136.

Mustaine, E. E., & Tewksbury, R. (2009). Rainmakers: the most successful criminal justice scholars and departments in research grant acquisition. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 20(1), 40–55.

Mustaine, E. E., & Tewksbury, R. (2008). Reviewers’ views on reviewing: an examination of the peer review process in criminal justice. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 19(3), 351–365.

Pogrebin, M. R. (2010). On the way to the field: reflections of one qualitative criminal justice professor’s experiences. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 21(4), 540–561.

Reisig, M. D. (2001). The champion, contender, and challenger: Top-ranked books in prison studies. The Prison Journal, 81(3), 389–407.

Rice, S. K., Cohn, E. G., & Farrington, D. P. (2005). Where are they now? Trajectories of publication “stars” from American criminology and criminal justice programs. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 16(2), 244–264.

Rice, S. K., Terry, K. J., Miller, H. V., & Ackerman, A. R. (2007). Research trajectories of female scholars in criminology and criminal justice. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 18(3), 360–384.

Shutt, J. E., & Barnes, J. C. (2008). Reexamining criminal justice “star power” in a larger sky: a belated response to Rice et al. on sociological influence in criminal justice. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 19(2), 215–228.

Sorensen, J. (2009). An assessment of the relative impact of criminal justice and criminology journals. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37(5), 505–511.

Sorenson, J., Snell, C., & Rodriquez, J. J. (2006). An assessment of criminal justice and criminology journal prestige. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 17(2), 297–322.

Tewksbury, R., Dabney, D. A., & Copes, H. (2010). The prominence of qualitative research in criminology and criminal justice scholarship. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 21(4), 391–411.

Tewksbury, R., DeMichele, M., & Miller, J. M. (2005). Methodological orientations of articles appearing in criminal justice’s top journals: who publishes what and where. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 16(2), 265–279.

Tewksbury, R., & Mustaine, E. E. (2001). Where to find corrections research: an assessment of research published in corrections specialty journals, 1990–1999. The Prison Journal, 81(4), 419–435.

Tewksbury, R., & Mustaine, E. E. (2011). How many authors does it take to write an article? An assessment of criminology and criminal justice research article author composition. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 22(1), 12–23.

Tewksbury, R., & Mustaine, E.E. (in press). Cracking open the black box of the manuscript review process: A look inside Justice Quarterly. Journal of Criminal Justice Education. doi:10.1080/10511253.2011.653650.

Vito, G. F., & Tewksbury, R. (2008). The great books in criminal justice: as ranked by elite members of the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 19(3), 366–382.

Worley, R. (2011). What makes them tick: Lessons on high productivity from leading Twenty-first century academic stars. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 22(1), 130–149.

Wright, R. A. (2002). Recent changes in the most cited scholars in criminal justice textbooks. Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(3), 183–195.

Wright, R. A., Malia, M., & Johnson, C. W. (1999). Invisible influence: a citation analysis of crime and justice articles published in leading sociology journals. Journal of Crime and Justice, 22(2), 147–169.

Wright, R. A., & Miller, J. M. (1999). The most-cited scholars and works in corrections. The Prison Journal, 79(1), 5–22.

Wright, R. A., & Sheridan, C. (1997). The most-cited scholars and works in women and crime publications. Women and Criminal Justice, 9(2), 41–60.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tewksbury, R., Connor, D.P. & Worley, R.M. Why the American Journal of Criminal Justice is a Great Place to Publish: A Research Note Examining Frequent Authors’ Experiences. Am J Crim Just 38, 341–347 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-012-9168-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-012-9168-0