Abstract

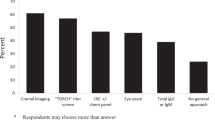

Infections acquired in utero or in the immediate post-natal period play a prominent role in perinatal and childhood morbidity. The TORCH constellation continues to be popular among perinatologists and paediatricians, although its limitations are increasingly known. A host of new organisms are now considered to be perpetrators of congenital and perinatal infections, and a diverse range of diagnostic tests are now available for confirming infection in the infant. In general, the collective TORCH serological panel has low diagnostic yield; instead individual tests ordered according to clinical presentation can contribute better towards appropriate diagnosis. This review captures the essence of established congenital infections such as cytomegalovirus, rubella, toxoplasmosis, syphilis and herpes simplex virus, as well as more recent entrants such as HIV and hepatitis B infection, varicella and tuberculosis. Selective screening of the mother and newborn, encouraging good personal hygiene and universal immunization are some measures that can contribute towards decreasing the incidence and morbidity of congenital and perinatal infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Nahmias A, Walls K, Stewart J, Hermann K, Flynt W. The ToRCH complex-perinatal infections associated with toxoplasma and rubella, cytomegol-and herpes simplex viruses. Ped Research. 1971;5(8):405.

Epps RE, Pittelkow MR, Su WP. TORCH syndrome. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14(2):179–86.

Greenough A. The TORCH screen and intrauterine infections. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1994;70(3):F163–5.

Stagno S, Pass RF, Dworsky ME, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: the relative importance of primary and recurrent maternal infection. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(16):945–9.

Boppana SB, Pass RF, Britt WJ. Virus-specific antibody responses in mothers and their newborn infants with asymptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infections. J Infect Dis. 1993;167(1):72–7.

Deorari AK, Broor S, Maitreyi RS, et al. Incidence, clinical spectrum, and outcome of intrauterine infections in neonates. J Trop Pediatr. 2000;46(3):155–9.

Dar L, Pati SK, Patro AR, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in a highly seropositive semi-urban population in India. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(9):841–3.

Kylat RI, Kelly EN, Ford-Jones EL. Clinical findings and adverse outcome in neonates with symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus (SCCMV) infection. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165(11):773–8.

Vauloup-Fellous C, Ducroux A, Couloigner V, et al. Evaluation of cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA quantification in dried blood spots: retrospective study of CMV congenital infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(11):3804–6.

Kimberlin DW, Lin CY, Sanchez PJ, et al. Effect of ganciclovir therapy on hearing in symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus disease involving the central nervous system: a randomized, controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2003;143(1):16–25.

Pass RF, Zhang C, Evans A, et al. Vaccine prevention of maternal cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(12):1191–9.

Gregg M. Congenital cataract following German measles in mother. Trans Ophthalmol Soc Aust. 1941;3:35–46.

Cutts FT, Robertson SE, Diaz-Ortega JL, Samuel R. Control of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) in developing countries, Part 1: burden of disease from CRS. Bull World Health Organ. 1997;75(1):55–68.

Broor S, Kapil A, Kishore J, Seth P. Prevalence of rubella virus and cytomegalovirus infections in suspected cases of congenital infections. Indian J Pediatr. 1991;58(1):75–8.

Peckham CS. Clinical and laboratory study of children exposed in utero to maternal rubella. Arch Dis Child. 1972;47(254):571–7.

Banatvala JE, Brown DW. Rubella. Lancet. 2004;363(9415):1127–37.

Progress toward elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome—the Americas, 2003–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57(43):1176–9.

Lappalainen M, Koskiniemi M, Hiilesmaa V, et al. Outcome of children after maternal primary Toxoplasma infection during pregnancy with emphasis on avidity of specific IgG. The Study Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14(5):354–61.

Singh S, Pandit AJ. Incidence and prevalence of toxoplasmosis in Indian pregnant women: a prospective study. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2004;52(4):276–83.

Mittal V, Bhatia R, Singh VK, Sengal S. Low incidence of congenital toxoplasmosis in Indian children. J Trop Pediatr. 1995;41(1):62–3.

Wilson CB, Remington JS, Stagno S, Reynolds DW. Development of adverse sequelae in children born with subclinical congenital toxoplasma infection. Pediatrics. 1980;66(5):767–74.

Chaudhary M, Kashyap B, Bhalla P. Congenital syphilis, still a reality in 21st century: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2007;1:90.

Woods CR. Syphilis in children: congenital and acquired. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2005;16(4):245–57.

Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1–94.

Kropp RY, Wong T, Cormier L, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infections in Canada: results of a 3-year national prospective study. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):1955–62.

Cowan FM, French RS, Mayaud P, et al. Seroepidemiological study of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in Brazil, Estonia, India, Morocco, and Sri Lanka. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(4):286–90.

Malm G, Forsgren M. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infections: HSV DNA in cerebrospinal fluid and serum. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1999;81(1):F24–9.

Stone KM, Brooks CA, Guinan ME, Alexander ER. National surveillance for neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. Sex Transm Dis. 1989;16(3):152–6.

Cantwell MF, Shehab ZM, Costello AM, et al. Brief report: congenital tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(15):1051–4.

Pal P, Ghosh A. Congenital tuberculosis: late manifestation of the maternal infection. Indian J Pediatr. 2008;75(5):516–8.

Vallejo JG, Ong LT, Starke JR. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of tuberculosis in infants. Pediatrics. 1994;94(1):1–7.

Connell T, Bar-Zeev N, Curtis N. Early detection of perinatal tuberculosis using a whole blood interferon-gamma release assay. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(11):e82–5.

Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children, 2006. World Health Organization, Geneva. Available at: http://www.who.int/child_adolescent_health/documents/htm_tb_2006_371/en/index.html, 2006.

Dworsky M, Whitley R, Alford C. Herpes zoster in early infancy. Am J Dis Child. 1980;134(6):618–9.

Smith CK, Arvin AM. Varicella in the fetus and newborn. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14(4):209–17.

Nguyen HQ, Jumaan AO, Seward JF. Decline in mortality due to varicella after implementation of varicella vaccination in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(5):450–8.

Chang MH. Hepatitis B virus infection. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;12(3):160–7.

Mortality Country Fact Sheet, India 2006. World Health Organization, Geneva. Available at http://www.who.int/whosis/mort/profiles/mort_searo_ind_india.pdf. 2006.

WHO Guidelines. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants in resource-limited settings. Towards universal access: recommendations for a public health approach. 2006.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Role of Funding Source

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shet, A. Congenital and Perinatal Infections: Throwing New Light with an Old TORCH. Indian J Pediatr 78, 88–95 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-010-0254-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-010-0254-3