Abstract

Stability of a dynamic equilibrium in a predator-prey system depends both on the type of functional response and on the point of equilibrium on the response curve. Saturation effects from Holling type II responses are known to destabilise prey populations, while a type III (sigmoid) response curve has been shown to provide stability at lower levels of saturation. These effects have also been shown in multi-trophic model systems. However, stability analyses of observed equilibria in real complex ecosystems have as yet not assumed non-linear functional responses. Here, we evaluate the implications of saturation in observed balanced material-flow structures, for system stability and sustainability. We first make the effects of the non-linear functional responses on the interaction strengths in a food web transparent by expressing the elements of Jacobian ‘community’ matrices for type II and III systems as simple functions of their linear (type I) counterparts. We then determine the stability of the systems and distinguish two critical saturation levels: (1) a level where the system is just as stable as a type I system and (2) a level above which the system cannot be stable unless it is subsidised, separating a stable materially sustainable regime from an unsustainable one. We explain the stabilising and destabilising effects in terms of the feedbacks in the systems. The results shed light on the robustness of observed patterns of interaction strengths in complex food webs and suggest the implausibility of saturation playing a significant role in the equilibrium dynamics of sustainable ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The functional response of a predator population is the change in its feeding rate per unit predator density relative to the change in the prey population density (Fig. 1). The type of response is crucial to the dynamics of the predator-prey system. If an increase in prey density does not lead to a corresponding increase in the food uptake by the predator, the predator will not be able to keep the prey population in check (May 1973). Oaten and Murdoch (1975) elegantly show how the stability of an equilibrium depends not only on the type of functional response but also, in particular, on the point of equilibrium on a functional response curve. They present a criterion in terms of the maximum equilibrium density for which a Holling III response (Holling 1959; Takahashi 1964) will be stabilising. The term stabilising here means that an increase or decrease in the prey density leads to a greater than proportionate increase or decrease in the rate of predation per predator (Oaten and Murdoch 1975). In other words, there will be a negative (corrective) feedback which is stronger than that resulting from a linear functional response (type I), where the change in predator uptake is proportional to the change in prey population. The Holling II response (Holling 1959 and 1965) is always destabilising. The relative stability of systems with type III versus II responses has been shown also for complex multi-trophic systems, in synthetic food web models (Oaten and Murdoch 1975; Gross et al. 2004, 2009; Williams and Martinez 2004; Brose et al. 2006).

Although these functional responses are commonly used in non-linear food-web models, local stability analyses (in the sense of May 1973) of observed equilibria in real multi-trophic communities (de Ruiter et al. 1995; Rooney et al. 2006; Neutel et al. 2007; Neutel and Thorne 2014) have as yet not assumed underlying non-linear functional responses. The rationale for this is that there is no empirical basis for more complex equations; the observations do not provide the parameter values for non-linear responses. Such local stability analyses have shown patterns in the strengths of the interactions among the populations that are crucial for system stability (de Ruiter et al. 1995; Neutel et al. 2007; Neutel and Thorne 2014; James et al. 2015), underpinning the importance of the organisation of many weak and few strong links in a community (Paine 1992; Polis 1994; McCann et al. 1998; Neutel et al. 2002) This raises the question how robust such patterns obtained from observed equilibria in real ecosystems are or to what extent the stability of these equilibria depends on the linear type of functional response assumed.

In analogy with Oaten and Murdoch (1975), we analysed how, for type II and III functional responses, the level of saturation affects the stability of an equilibrium, comparing it to the stability with type I responses. We did this for complex multi-trophic food webs. A more general, abstract framework for the evaluation of unknown functions and parameter values in multi-trophic food webs has been offered by Gross and Feudel (2006). Our aim was not to provide a new approach to this general problem but to make the effects of simple non-linear functional responses on the community matrix of observed equilibria transparent and explain the consequences for system stability by quantifying the feedbacks in the system. We first expressed the values of the interaction strengths of community matrices with underlying Holling II and III type functional responses in terms of their type I counterparts. We then modelled stability using observed equilibria in real ecosystems for which the fluxes were known and found critical saturation levels for stability and sustainability.

Methods

Model formulation

Let the dynamics of a population X i (with X referring to its biomass) of each population i = 1 … n in a food web be described by

where f i (X h ) is the functional response in a consumer, r i and m i are the intrinsic growth and loss rates (we assume net intrinsic growth for basal species and r i = 0 for non-basal species), c ii is a proportionality constant referring to intraspecific competition and e hi is the biomass conversion efficiency. All parameters are defined positive. The Jacobian ‘community’ matrix, a linearisation of the system around the non-trivial equilibrium (where each species has a positive population density), is specified by the partial derivatives of the above differential equations evaluated at equilibrium (May 1973).

Linear functional response

In the case of linear functional responses (type I), Eq. (1) becomes a Lotka-Volterra type equation with intraspecific competition terms (see for example Pimm 1982):

where c ij and c hi are proportionality constants (dimension per biomass per time). The elements of the community matrix Α on row i are effects of predator j on prey i, α ij = − c ij X ∗ i , effects of prey h on consumer i, α ih = e hi c hi X * i , and intraspecific effects α ii = − c ii X ∗ i (since at equilibrium, \( {r}_i-{m}_i+\sum_{h=1}^n{e}_{hi}{c}_{hi}{X}_h-\sum_{j=1}^n{c}_{ij}{X}_j-{c}_{ii}{X}_i=0 \)).

Thus, the effects of a predator j on its prey i and vice versa (the latter are partial derivatives of predator j’s growth equation with respect to the size of species i) are related to each other (Pimm 1982) according to \( {\alpha}_{ji}={e}_{ij}{c}_{ij}{X}_j^{*}=-{e}_{ij}{\frac{X_j^{*}}{X_i^{*}}}^{*}{\alpha}_{ij}. \)

Assuming that the equilibrium biomass densities X * i and feeding rates f j (X i )* and the biomass conversion efficiency values e ij can be directly obtained from observation, such observational values give us the off-diagonal elements of community matrix Α:

Non-linear functional response

Now we replace the linear functional response by a non-linear one, incorporating f j (X i ) = b ij X g i /(D g i + X g i ) in Eq. (1), where b ij is a proportionality constant, generally referred to as search or attack rate (dimension per time), D i is the prey population level where the predation rate per unit predator is half its maximum value and g is a positive integer indicating the type of response. We used the most weak form of non-linear functional response where the predator’s consumption rate on each prey type depends only on that prey’s density and prey types cannot compensate for each other. For g = 1 and g = 2, we have Holling type II (Holling 1959, 1965) and Holling type III (Holling 1959; Takahashi 1964) functional responses, respectively. Note that the non-linearity in the responses is limited to the dependence on the prey, i.e. there is a linear numerical response (dependence of growth and predation terms on predator density). For the community matrix (Γ), this means that the elements γ ij representing effects of predators j on prey i (partial derivatives with respect to predator density) are predation rates relative to predator population size in equilibrium, just as in the case of Lotka-Volterra-type equations:

The effects of prey i on their predator j are partial derivatives with respect to prey density:

Mathematical analysis

In order to analyse the saturation levels at equilibrium, we expressed the half saturation value in terms of the equilibrium population size, D i g = kX * i g, rewriting the effects of predators j on prey i, \( {\gamma}_{ij}=-\frac{1}{k+1}{b}_{ij} \) and effects of prey i on their predator j, \( {\gamma}_{ji}=g{e}_{\mathrm{ij}}\frac{b_{ij}k{\left({X_i^{*}}^g\right)}^2{X}_j^{*}}{X_i^{*}{\left(\left(k+1\right)\left({X_i^{*}}^g\right)\right)}^2} = \frac{k}{{\left(k+1\right)}^2}\ \frac{X_j^{*}}{X_i^{*}}g{e}_{\mathrm{ij}}{b}_{ij} \), where k is some positive number. Thus, the effects of prey i on their predator j are \( {\gamma}_{ji} = -\frac{k}{k+1}\ \frac{X_j^{*}}{X_i^{*}}g{e}_{\mathrm{ij}}{\gamma}_{ij} \) and in terms of their type I counterparts, using Eq. (3),

The intraspecific effects (partial derivatives evaluated at equilibrium) are

In equilibrium, the population sizes do not change; therefore, Eq. (1) is set to zero:

Subtracting the left-hand side of Eq. (8) from Eq. (7), this can be reduced to

This can be rewritten in terms of the off-diagonal elements, using Eqs. (4) and (5),

and can be expressed in terms of the elements of Α

where j is a predator and i is its prey. Equation (9) directly shows how the relation between the diagonal elements resulting from assuming non-linear functional responses and their type I counterparts depends directly on the effect of non-linearity in the functional response on the positive off-diagonals. If the linear and non-linear functional responses result in the same positive off-diagonals, non-linearity of the functional response also has no effect on the diagonals and matrix Γ will be the same as Α. Tables 1 and 2 present an overview for type II (g = 1) and III (g = 2) community matrix element values. They specify three levels of saturation, k → 0, in which case the system is fully saturated, at the half-saturation value k = 1, and k ≫ 1, in which case the system is very undersaturated.

Intraspecific competition as a control parameter

We used the level of intraspecific competition as a control parameter, following Neutel et al. (2002). The rationale is as follows. For a given food web in equilibrium, with known biomass densities X * i , feeding rates f j (X i )* and biomass conversion-efficiency values e ij , the non-predatory loss rates are also known, since in equilibrium total loss for each population equals total gain. This total non-predatory loss rate consists of intrinsic death and intraspecific competition: d i X * i = m i X * i + c ii X * 2 i . The amount of intraspecific competition may not be known but it is contained within the energetic boundaries of the system 0 ≥ c ii X * i ≥ d i . The level of intraspecific competition relative to the total non-predatory loss at equilibrium was our control parameter s, \( s=\frac{c_{ii}{X}_i^{*}}{d_i} \), where 0 ≤ s ≤ 1.

In our analyses, we determined for which values of s the maximum real part of the eigenvalues was just below zero, that is, we used s to make the system just stable (Neutel et al. 2002). This critical value of intraspecific competition was called s*. In the case of linear functional responses, intraspecific competition directly represents the diagonal elements α ii = − c ii X * i = − sd i . In the case of non-linear functional responses, the interspecific interactions also contribute to self-damping or self-enhancing effects and add a value to the diagonal elements (see Eq. (9)). This means that we used the variable s to compensate also for possible diagonal effects caused by the non-linear functional responses.

Feedback metric

To analyse the effects of non-linear functional responses on the stability of a community, we used the metric \( \sqrt[3]{\left|\frac{a_3}{a_2}\right|} \) proposed by Neutel and Thorne (2014), where a 2 and a 3 are the coefficients of the characteristic polynomial of the community matrix. In a matrix with zero diagonal elements, the second coefficient, a 2, represents the sum of all the two-link feedback loops (Levins 1974), resulting from the pairs of predator-prey interactions, which are by definition negative: F 2 = ∑γ ij γ ji . The third coefficient, a 3, represents the sum of all the three-link loops, coming from the smallest omnivorous structures, each generating a positive and a counteracting negative feedback loop: F 3 = ∑(γ ij γ jk γ ki + γ ik γ kj γ ji ), where i is the bottom prey, j is the intermediate predator and k is the omnivore. It has been shown for type I systems that the sum of the positive and counteracting negative loop in each three-link omnivorous structure is by definition positive (Neutel and Thorne 2014),

Using Eq. (6), these feedbacks in type II and III systems could be expressed in terms of the type I matrix elements:

Equation (10) shows that for higher levels of saturation (small k), the negative three-link loops will be relatively weak and hence net positive feedback will be relatively strong. This relatively strong positive feedback can be expected to decrease stability. Note that the two-link loops and the positive three-link loops contain one, and the negative three-link loops contain two positive elements. Note also that for k = 0, the positive off-diagonal elements will be zero and there will be no interspecific feedback, neither positive nor negative. In this extreme case, the feedback metric has no meaning.

Results

Table 1 shows how for type II responses, saturation leads to smaller positive off-diagonal interaction strength and adds positive (self-enhancing) diagonal effects. Only extreme undersaturation (very large k) leads to community matrices similar to type I. Table 2 shows how for type III responses, half-saturation (k = 1) results in the same matrix as that of type I systems. Less saturation (k > 1) will result in larger positive off-diagonal interaction strength and will add negative (self-damping) diagonal effects. More saturation (k < 1) will result in smaller positive off-diagonal interaction strength and adds positive (self-enhancing) diagonal effects, just as in type II systems.

We evaluated the effect of these non-linear functional responses on the stability of observed equilibria. For this analysis, we used the food webs of terrestrial Antarctic ecosystems described by Neutel and Thorne (2014), where, averaged over time, material-flux observations showed a steady state. The observed equilibrium biomass densities X i *, equilibrium feeding rates f j (X i )*, and biomass conversion efficiency values provided us with the type I Jacobian community matrix Α (Neutel and Thorne 2014). In our stability calculations for type II and III functional responses, we assumed for simplicity’s sake that all species in a system had the same type of functional response. As was evident from Tables 1 and 2, very undersaturated type II systems had similar stability, and the half-saturated type III system had the same stability as that of the type I system. The material basis of the community matrices allowed us to distinguish two different stability zones: stable and sustainable (where the critical level of intraspecific interaction s* ≤ 1) and stable but not energetically feasible unless subsidised (s* > 1). Saturation (smaller values of k) rapidly enhanced the critical level of intraspecific competition of communities in type II systems and did the same for saturation levels beyond half-saturation (k < 1) in type III models (Fig. 2). For type II systems, even low levels of saturation already led to an unsustainable system. Figure 2 shows the results for the dry Antarctic tundra ecosystem, which has a very low level of critical intraspecific competition with type I dynamics. Less stable food webs, with higher levels of critical intraspecific competition in the type I case, were found to result in much stronger saturation effects from type II and III responses, that is, they led to even higher levels of critical intraspecific competition, already at lower saturation levels (larger values of k).

Local stability of an observed food web in equilibrium, assuming non-linear functional responses of types II and III. The curve shows the relation between undersaturation level (k) and critical level of intraspecific competition (s*), where s* is the amount needed to make the system just stable, that is, where the maximum real part of the eigenvalues is just below zero (see “Methods”). The red dotted line indicates s* of the system assuming a linear (type I) functional response. In the green zone, the systems are stable and materially sustainable; in the red zone, they are stable but materially unsustainable given the equilibrium feeding rates, unless subsidy from outside the system is assumed. The white zone below the curve is the unstable zone, but note that the whole state space (the whole graph area) refers to mathematically and physically feasible equilibria. The figure shows the stability results for the Antarctic dry tundra ecosystem (Neutel and Thorne 2014), but the tendencies are representative of other observed complex food webs

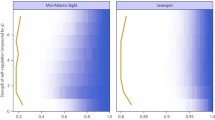

We then separated the effects of non-linearity on the off-diagonal patterns from those on the diagonal, by removing the diagonal effects caused by type II or III functional responses from the community matrices. The change in off-diagonal patterns of interaction strengths caused by the non-linear functional responses hardly affected stability (Fig. 3a). Higher levels of saturation caused smaller positive interaction strengths (Tables 1 and 2). Lower levels of saturation in type III systems caused larger positive interaction strengths (Table 2). This affected the negative two-link predator-prey feedbacks, but it also impacted on the longer negative and positive feedbacks, resulting in an increase or decrease in net positive three-link feedback (see “Methods”). Figure 3b shows that the impact of the changes in off-diagonal matrix elements on stability (measured as the largest real part of the eigenvalues) could be quantified by the feedback metric \( \sqrt[3]{\left|\frac{a_3}{a_2}\right|} \) (Neutel and Thorne 2014), where a 3 and a 2 are the total three-link and two-link feedback in a system. The decrease in stability with saturation turned into an increase at very high levels of saturation, when the positive interaction strengths became so small that there was effectively not enough off-diagonal feedback left to destabilise the system (Fig. 3b), so that, at full saturation, virtually no intraspecific competition was needed to provide stability (Fig. 3a).

Local stability of the observed food web shown in Fig. 2, with type II and III responses but with the diagonal effects of non-linear functional responses removed. a Impact of k on s*, showing a slightly destabilising effect (increase in s*) of saturation (decrease in k). b Relation between the maximum real part of the eigenvalues of the community matrices without diagonal elements (Γ 0 ) and the strength of three-link and two-link feedback loops in these matrices, with varied levels of k. We used the feedback metric proposed by Neutel and Thorne (2014). See “Methods” for an explanation of this feedback metric. The metrics were relative to the type I value, \( {\lambda}_d^{\prime }=\frac{\lambda_d\left({\varGamma}_0\right)}{\lambda_d\left({A}_0\right)} \) and \( {\sqrt[3]{\left|\frac{a_3}{a_2}\right|}}^{\prime }=\frac{\sqrt[3]{\left|\frac{a_3}{a_2}\right|}\left({\varGamma}_0\right)}{\sqrt[3]{\left|\frac{a_3}{a_2}\right|}\left({A}_0\right)} \). The relation between stability and feedback explains the destabilising effect of saturation shown in a. At very high values of k (no saturation, bottom left of the curve), the systems are most stable (low λ d ). Stability decreases with saturation up to the point where it suddenly increases again (top right of the curve). As k → 0, the effects of prey on their predators become very small (Tables 1 and 2) and the resulting feedback becomes too weak to destabilise the system (λ d → 0). Note that at k = 0 the feedback metric is not defined

Since the large decline in stability with increasing saturation shown in Fig. 2 could not have been caused by a change in patterns of the interspecific interaction strengths (Fig. 3), we concluded that it was effectively the change in the diagonal elements which was responsible for the stability effects. In Tables 1 and 2, the expressions for the intraspecific effects quantify the self-damping or self-enhancing feedback caused by non-linear functional responses, and hence, they directly specified the destabilising or stabilising effects of type II and III systems, compared to type I systems.

Discussion

By deriving Jacobian community matrices for predator-prey systems with the weakest form of Holling type II and III functional responses, we made the stabilising and destabilising effects of these non-linear functional responses transparent. We found that saturation has such a strong self-enhancing effect on the populations and that communities at equilibrium, in order to maintain their stability, need levels of intraspecific competition far beyond the energetic constraints of the system. We therefore conclude that, unless systems are highly subsidised, that is, the populations receive their main energy input from external sources, it is implausible that saturation plays a significant role in multi-trophic equilibrium dynamics.

Implausibility of Holling-type saturation

Our type II and III models assumed only the weakest form of saturation, that is, relative feeding rates of predators on a certain prey only saturated with an increase of that prey type and were not dependent on other, alternative prey. More common forms of type II and III models, which assume that prey types in a predator’s diet can compensate for each other, would have caused different stability properties. However, dependence of a predator-prey interaction on all prey in a predator’s diet leads to added weak mutualistic effects between prey populations (Gross and Feudel 2006) and to saturation of a predator at even lower densities of its specific prey (since feeding depends on the total biomass of a predator’s prey). Both effects add to the positive feedback in the system and can therefore be expected to result in even higher levels of critical intraspecific competition.

The material basis of our models allowed us to evaluate the consequences of saturation effects for the energetic feasibility of multi-trophic equilibria. Our findings from observed equilibria suggest that saturation resulting from Holling II or III functional responses is not likely to play a role in the kinds of patterns of interaction strengths that we observe in nature, since these responses result in unsustainable systems already at relatively low saturation levels.

Other and more complex types of functional response have been proposed (Ivlev 1961; Jassby and Platt 1976; Beddington 1975; DeAngelis et al. 1975; Arditi and Ginzburg 1989), with consequences for stability. Even apparently similar curves can have very different stability results depending on the level of saturation (Fussmann and Blasius 2005). Our findings from Holling type II and III responses are in coherence with evolutionary food web model analyses showing that stable, diverse multi-trophic level patterns with many weak and strong links as found in empirically based food web studies (Paine 1992; Polis 1994; de Ruiter et al. 1995) naturally emerge from adapted Lotka-Volterra type or ratio-dependent population-dynamical functions but not from common or adapted Holling-type responses (Drossel et al. 2004).

Analysing the effects of non-linear functional responses on stability

The destabilising effect of saturation resulting from Holling II and III functional responses and the relative stability of type III compared to type II systems are well known for multi-trophic communities (Gross et al. 2004, 2009). We analytically derived community matrices for type II and III systems in terms of type I matrix elements, separated the effects on stability resulting from the off-diagonal patterns from those resulting from the diagonal elements, and explained these effects, using a recently proposed feedback metric (Neutel and Thorne 2014). By doing this, we provided a mechanistic understanding of the consequences of non-linear functional responses for system stability.

The patterning of strong and weak interaction strengths in the systems was found to be very robust, in the sense that while saturation effects from type II and III responses led to different off-diagonal interaction strengths than those resulting from type I responses, these differences hardly affected system stability. The off-diagonal effects on stability could be understood from the change in negative three-link feedback loops, resulting in a relatively strong net positive three-link feedback. The robustness of the off-diagonal patterns sheds light on the structural stability of food web models and emphasises the importance of model parameterisation in network stability analyses (Neutel and Thorne 2014; Rohr et al. 2014). It underpins the remarkable balance between positive and negative feedbacks resulting from the natural patterning of strong and weak links in multi-trophic equilibria, leading to only very little intraspecific competition needed to stabilise a community (Yodzis 1981; de Ruiter et al. 1995; Neutel et al. 2002; Neutel and Thorne 2014; James et al. 2015).

Our stability results showed that in complex communities, the destabilising effect of saturation is neither that the corrective force of the predator population on the prey is diminished (May 1973) nor is it the weakening of the longer negative feedbacks that has a significant effect. Saturation in type II systems (and more-than-half saturation in type III systems) adds a positive term to the diagonal elements, which explains the strong destabilising effect. This self-enhancing feedback has to be compensated for by intraspecific competition, in order to maintain stability. We found that saturation required very high levels of compensatory intraspecific competition. Our results for complex multi-trophic systems mirrored recent findings in small, single-interaction model systems parameterised from experiments (Johnson and Amarasekare 2015).

Ecological relevance

We found two stable regimes: one that is sustainable and largely undersaturated and one that is unsustainable (unless subsidised) and has some level of saturation. This offers a new perspective on the paradox of enrichment (Rosenzweig 1971): saturation causes instability (Gross et al. 2004), unless it is accompanied by an increase in intraspecific competition to a level that takes it beyond the carrying capacity of the system, which is only possible if the system is subsidised (enriched) with material from outside. Thus, enrichment in our models was not forced upon the system as a changed input parameter but was an emergent property of the system’s equilibrium dynamics. Our results suggest that we might find saturation playing a role in the steady state of natural systems in circumstances where all non-predatory death is due to intraspecific competition (there is no death through old age), with a large input from allochtonous material. These circumstances can be found in open, aquatic systems. Thus, the results hint at observed shifts between oligotrophic and eutrophic conditions (Gross et al. 2004; Scheffer and Carpenter 2003). On the other hand, the levels of competition and subsidy required may be too high for complex natural communities, and saturation has in fact been found to lead to a relatively simple trophic structure (Drossel et al. 2004). Nature’s complexity in general is hungry and has to be in order to be stable.

References

Arditi R, Ginzburg LR (1989) Coupling in predator–prey dynamics: ratio dependence. J Theor Biol 139:311–326. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(89)80211-5

Beddington JR (1975) Mutual interference between parasites or predators and its effect on searching efficiency. J Anim Ecol 44:331–340. doi:10.2307/3866

Brose U, Williams RJ, Martinez ND (2006) Allometric scaling enhances stability in complex food webs. Ecol Lett 9:1228–1236. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00978.x

de Ruiter PC, Neutel AM, Moore JC (1995) Energetics, patterns of interaction strengths, and stability in real ecosystems. Science 269:1257–1260. doi:10.1126/science.269.5228.1257

DeAngelis DL, Goldstein RA, O’Neill RV (1975) A model for trophic interaction. Ecology 56:881–892. doi:10.2307/1936298

Drossel B, McKane AJ, Quince C (2004) The impact of nonlinear functional responses on the long-term evolution of food web structure. J Theor Biol 229:539–548

Fussmann GF, Blasius B (2005) Community response to enrichment is highly sensitive to model structure. Biol Lett 1:9–12. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0246

Gross T, Feudel U (2006) Generalized models as a universal approach to the analysis of nonlinear dynamical systems. Phys Rev E 73:016205. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.73.016205

Gross T, Ebenhöh W, Feudel U (2004) Enrichment and food chain stability: the impact of different forms of predator-prey interaction. J Theor Biol 227:349–358. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2003.09.020

Gross T, Rudolf L, Levin SA, Dieckmann U (2009) Generalized models reveal stabilising factors in food webs. Science 325:747. doi:10.1126/science.1173536

Holling CS (1959) The components of predation as revealed by a study of small-mammal predation of the European pine sawfly. Can Entomol 91:293–320. doi:10.4039/Ent91293-5

Holling CS (1965) The functional response of predators to prey density and its role in mimicry and population regulation. Mem Entomol Soc Can 45:1–60. doi:10.4039/entm9745fv

Ivlev VS (1961) Experimental ecology of the feeding of fishes. Yale University Press, New Haven

James A, Plank MJ, Rossberg AG, Beecham J, Emmerson M, Pitchford JW (2015) Constructing random matrices to represent real ecosystems. Am Nat 185:680–692. doi:10.1086/680496

Jassby AD, Platt T (1976) Mathematical formulation of the relationship between photosynthesis and light for phytoplankton. Limnol Oceanogr 21:540–547

Johnson CA, Amarasekare P (2015) A metric for quantifying the oscillatory tendency of consumer-resource interactions. Am Nat 185:87–99. doi:10.1086/679279

Levins R (1974) The qualitative analysis of partially specified systems. Ann N Y Acad Sci 231:123–138. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb20562.x

May RM (1973) Stability and complexity in model ecosystems. Princeton University Press, Princeton

McCann K, Hastings AG, Huxel R (1998) Weak trophic interactions and the balance of nature. Nature 395:794–798. doi:10.1038/27427

Neutel AM, Thorne MAS (2014) Interaction strengths in balanced carbon cycles and the absence of a relation between ecosystem complexity and stability. Ecol Lett 17:651–661. doi:10.1111/ele.12266

Neutel AM, Heesterbeek JAP, de Ruiter PC (2002) Stability in real food webs: weak links in long loops. Science 296:1120–1123. doi:10.1126/science.1068326

Neutel AM et al (2007) Reconciling complexity with stability in naturally assembling food webs. Nature 449:599–602. doi:10.1038/nature06154

Oaten A, Murdoch WW (1975) Functional response and stability in predator–prey systems. Am Nat 109:289–298

Paine RT (1992) Food-web analysis through field measurement of per capita interaction strength. Nature 355:73–75. doi:10.1038/355073a0

Pimm SL (1982) Food webs. Chapman & Hall, London

Polis GA (1994) Food webs, trophic cascades and community structure. Aust J Ecol 19:121–136. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.1994.tb00475.x

Rohr RP, Saavedra S, Bascompte J (2014) On the structural stability of mutualistic networks. Science 345:1253497. doi:10.1126/science.1253497

Rooney N, McCann K, Gellner G, Moore JC (2006) Structural asymmetry and the stability of diverse food webs. Nature 442:265–269. doi:10.1038/nature04887

Rosenzweig ML (1971) Paradox of enrichment: destabilization of exploitation ecosystems in ecological time. Science 171:385–387. doi:10.1126/science.171.3969.385

Scheffer M, Carpenter SR (2003) Catastrophic regime shifts in ecosystems: linking theory to observation. Trends Ecol Evol 18:648–656. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2003.09.002

Takahashi F (1964) Reproduction curve with two equilibrium points: a consideration on the fluctuation of insect population. Res Popul Ecol 6:28–36

Williams RJ, Martinez ND (2004) Stabilization of chaotic and non-permanent food-web dynamics. Eur Phys J B 38:297–303. doi:10.1140/epjb/e2004-00122-1

Yodzis P (1981) The stability of real ecosystems. Nature 289:674–676. doi:10.1038/289674a0

Acknowledgments

We thank Thilo Gross and an anonymous reviewer for comments on the manuscript. This work is part of the British Antarctic Survey Polar Science for Planet Earth Programme. It was funded by The Natural Environment Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Neutel, AM., Thorne, M.A.S. Linking saturation, stability and sustainability in food webs with observed equilibrium structure. Theor Ecol 9, 73–81 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-015-0270-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-015-0270-z