Abstract

Studies of time-invariant matrix metapopulation models indicate that metapopulation growth rate is usually more sensitive to the vital rates of individuals in high-quality (i.e., good) patches than in low-quality (i.e., bad) patches. This suggests that, given a choice, management efforts should focus on good rather than bad patches. Here, we examine the sensitivity of metapopulation growth rate for a two-patch matrix metapopulation model with and without stochastic disturbance and found cases where managers can more efficiently increase metapopulation growth rate by focusing efforts on the bad patch. In our model, net reproductive rate differs between the two patches so that in the absence of dispersal, one patch is high quality and the other low quality. Disturbance, when present, reduces net reproductive rate with equal frequency and intensity in both patches. The stochastic disturbance model gives qualitatively similar results to the deterministic model. In most cases, metapopulation growth rate was elastic to changes in net reproductive rate of individuals in the good patch than the bad patch. However, when the majority of individuals are located in the bad patch, metapopulation growth rate can be most elastic to net reproductive rate in the bad patch. We expand the model to include two stages and parameterize the patches using data for the softshell clam, Mya arenaria. With a two-stage demographic model, the elasticities of metapopulation growth rate to parameters in the bad patch increase, while elasticities to the same parameters in the good patch decrease. Metapopulation growth rate is most elastic to adult survival in the population of the good patch for all scenarios we examine. If the majority of the metapopulation is located in the bad patch, the elasticity to parameters of that population increase but do not surpass elasticity to parameters in the good patch. This model can be expanded to include additional patches, multiple stages, stochastic dispersal, and complex demography.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many populations of organisms are distributed among patches that vary in quality. When organisms move between these patches, thereby connecting them, the collection of patches is termed a “metapopulation.” When managing a metapopulation, effort must be allocated among patches and life cycle stages because of inevitable limitations on time, manpower, and money. One way to approach this allocation problem, and the motivation of this paper, is to develop a method for determining the potential impact of changes in patch-specific population parameters, particularly when the metapopulation in question is subject to stochastic disturbance.

The simpler problem of allocating effort among life cycle stages within a single population has been approached using elasticity analyses of the population growth rate (e.g., Crouse et al. 1987; Parker 2000; Aires-da Silva and Gallucci 2007; Kesler and Haig 2007; Raithel et al. 2007; Enneson and Litzgus 2008). The assumption is that, all else being equal, if population growth rate is very elastic to a parameter, then that parameter is a good target for management efforts. In this paper, we will show that the elasticities of the stochastic metapopulation growth rate can be used to extend this approach and identify both locations and stages that are good targets for management.

Previous theoretical studies of metapopulations (e.g., Pulliam 1988; Runge et al. 2006) have suggested that management should focus on patches where demographic rates (survival, reproduction, and growth) are most favorable. Using elasticity analyses of progressively more complex models, we examine when this rule of thumb is correct and when it is not. Firstly, we analyze a deterministic two-patch metapopulation without stage structure. We then add environmental stochasticity. Finally, we include stage structure and a life cycle model that conforms with the softshell clam, Mya arenaria.

One-stage, deterministic model

Imagine a metapopulation consisting of two patches. Let n i (t) be the population density in patch i at time t, referred to hereafter as population i. Two processes acting sequentially will change n i (t). Firstly, individuals survive and reproduce with a net per capita rate R i in patch i. Next, a proportion m i of individuals from patch i emigrate to patch j (Fig. 1). We can combine these two processes in the following matrix model to project the population from time t to t + 1:

where \(\mathbf{n}(t) = \left[n_1(t) , n_2(t)\right]^{\mathsf{T}}\) and

We set R 1 > 1 and R 2 < 1, so that in the absence of migration, population 1 is increasing in size and population 2 is decreasing in size (hereafter “good” and “bad” patches, respectively). The metapopulation growth rate λ is the dominant eigenvalue of A, and the stable patch distribution w is the right eigenvector corresponding to λ.

We used sensitivity analysis to determine the relative effects of changes to R 1 and R 2 on λ. The sensitivities of λ to the elements of A are given by the sensitivity matrix with entries

This matrix is

where v is the left eigenvector corresponding to λ (Caswell 2001). The entries of S depend on the combination of parameters that make up the corresponding a ij . A more interesting analysis is the sensitivity of λ to the lower-level parameters that compose A. From Chapter 9 Caswell (2001), we calculate the proportional sensitivity, or elasticity, of λ to the lower-level parameter R i as

To compare the effects of changes in per capita growth rate in the two patches on λ, we define the elasticity ratio of λ to R i as

If E > 1, then λ is more elastic to changes in R 1. If E < 1, then λ is more elastic to changes in R 2. Using Eqs. 4–6, we can write an expression for E in terms of the model parameters R i and m i and entries of the right and left eigenvectors v and w:

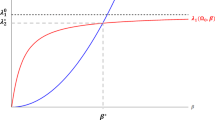

Figure 2 shows logE for different combinations of net reproductive rates, with m 1 and m 2 ranging from zero to one. E = 1 (the dashed line in Fig. 2) when

To the left of this line (as m 1 decreases), E > 1 and increasing R 1 results in the largest proportional increase in λ. To the right of this line (as m 1 increases), E < 1 and increasing R 2 results in the largest proportional increase in λ. That is, if individuals in the good patch tend to stay in that patch, then regardless of the fraction of individuals who migrate out of the bad patch (m 2), metapopulation growth rate is more elastic to changes in R 1 than R 2. As migration out of the good patch (m 1) increases, the proportion of individuals located in the bad patch also increases and E becomes less than 1.

The transition from λ < 1 to λ > 1 indicates where the metapopulation switches from declining to growing. As one might expect, increasing net reproductive rate in either patch increases the area of parameter space where λ > 1 (shaded areas in Fig. 2). A proportional increase in R 1, however, results in a greater proportion of space where λ > 1 than the same increase in R 2.

There are instances when E < 1 and λ > 1 (Fig. 2b, d). That is, there are times when the metapopulation growth rate is positive and is more sensitive to net reproductive rate in the bad patch. In these instances, migration rates are such that the majority of the metapopulation is found in the bad patch. The dotted lines on Fig. 2b–d are where the population is evenly distributed among patches. To the left of this line, there are more individuals in patch 1; to the right of this line, there are more individuals in patch 2. Cases where E < 1 and λ > 1 are always below the line. By solving for the stable structure from the matrix (Eq. 2), it can be shown that E < 1 only if the majority of the population is in the bad patch; i.e., that the dashed line in Fig. 2 is always to the right of the dotted line. One might assume that when the majority of individuals are in the bad patch, then metapopulation growth rate would be negative; however, this clearly is not always the case. The above result indicates that increasing R 2 has a larger effect because it impacts more individuals than increasing R 1. It also suggests that not only should individual patch growth rates be considered when determining where management efforts should be focused, but also the distribution of individuals among patches within the metapopulation.

One-stage, stochastic model

Metapopulations in nature are subject to stochastic environmental variability. Environmental variation may take many forms. Most commonly it is considered as underlying variability in the model parameters, or as events that are more intense but only occur sporadically (e.g., disturbance or catastrophes). Underlying variability would cause uncertainty in the results of Fig. 2 but would not be expected to change the observed patterns. Effects of disturbance are more difficult to predict. We model disturbance as a random event that occurs with probability p and reduces population size in patch i by a proportion δ i (t) that varies stochastically:

To construct \(\boldsymbol{\delta}(t) = [\delta_{1}(t), \delta_{2}(t)]^{\mathsf{T}}\), we first let x i (t) be an indicator variable for the event that population i is disturbed, such that

and these events form the random vector x(t). We assume that x(t) is drawn from a bivariate Bernoulli distribution (Marshall and Olkin 1985). We set the expectation

so that the patches are disturbed with equal probability at each time. Then

where D is a measure of disturbance intensity. Given that patch i is disturbed, x i (t) = 1 and population i is reduced by the proportion D. Large values of D equate to high disturbance intensity. Conversely, δ(t) is the proportion that survive the disturbance (1 − D).

Disturbance may occur at the two patches independently, or may be positively or negatively correlated. For example, a large-scale weather event such as a hurricane that affected all patches in a metapopulation would create a positive covariance of patch disturbance (c). Alternatively, a rotating harvest schedule where one patch is harvested, and the other is not, would create a negative covariance of patch disturbance. With \(c = \mbox{cov}(x_1, x_2)\), the variance–covariance matrix for x(t) is the constant matrix

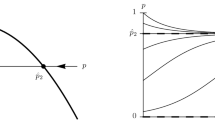

One can show that p and c must satisfy the constraints

and that the sum of the probabilities of all possible disturbance events equals 1. The constraints 14–16 define a two-dimensional parameter space of all allowable combinations of p and c (Fig. 3).

Including disturbance, the deterministic projection matrix (Eq. 2) becomes the stochastic matrix

The stochastic growth rate

is the long-term average growth rate of every realization of the model with probability 1 (Furstenberg and Kesten 1960; Cohen 1976; Tuljapurkar and Orzack 1980; Caswell 2001). The sensitivity analysis of stochastic growth rate was introduced by Tuljapurkar (1990) and extended to lower-level parameters by Caswell (2005). The elasticity of the stochastic growth rate to the net reproductive rate in patch i is

It gives the proportional change in logλ s , resulting from a proportional change in R i . In Eq. 19, v(t) and w(t) are the stochastic analogs to the left and right eigenvectors of the deterministic projection matrix, and r(t) is the one-step growth rate

(Caswell 2005, Eqs. 2–4). We define the stochastic elasticity ratio of logλ s to the R i as

As in the deterministic case, if E s > 1 then logλ s is more elastic to changes in R 1. Conversely, if E s < 1, then logλ s is more elastic to changes in R 2.

We calculated logλ s and the elasticity ratio (Eq. 21) for R 1 = 2.5, R 2 = 0.9, D = 0.9 (corresponding to the deterministic case in Fig. 2b), and for four migration scenarios in which the emigration rates are high or low:

We evaluated Eqs. 18 and 19 by Monte Carlo simulation with \(T=10\text{,}000\). As in the deterministic case, the elasticity ratio is correlated with the distribution of individuals among patches (Fig. 4). Determining where the majority of individuals are located is not as straightforward in the stochastic case. Rather than determine this based on migration rates, we must instead calculate the long-term average patch distribution.

Contour plots of logE s over the range of possible values for disturbance parameters p and c , for four combinations of m 1 and m 2. Shaded regions indicate where logλ s > 0. For all panels, R 1 = 2.5, R 2 = 0.9, and D = 0.9. Here logE s is used to show the details of the response of logλ s at small values and for comparing results to the no disturbance case (Fig. 2)

Figure 5a shows that in Fig. 4a, there are, on average, more individuals in patch 1 than in patch 2 because few individuals leave patch 1 (m 1 = 0.1) and most individuals from patch 2 migrate to patch 1 (m 2 = 0.9). As expected, elasticity ratio is greater than 1 and changes to the good patch will result in proportionally greater increases in metapopulation growth rate.

In the case where migration rates are equal (Fig. 4b, c), the majority of metapopulation individuals are located where most individuals originating from the good patch ultimately settle (patch 2 in the case where m 1, m 2 = 0.9, Fig. 5b; patch 1 in the case where m 1, m 2 = 0.1, Fig. 5c). Again, the elasticity ratio is greater than 1.

The result changes if emigration from patch 1 is high and emigration from patch 2 is low (Fig. 4d). Migration rates in this case result in more individuals, on average, in patch 2 (Fig. 5d). Consequently, E s < 1 for all combinations of disturbance parameters p and c. These results parallel those of the deterministic model: E s < 1 only if there are a lot more individuals on average in patch 2 than in patch 1. Changes to parameters in patch 2 thus will affect more individuals of the metapopulation, resulting in a proportionally greater increase in metapopulation growth rate.

E s also is affected by disturbance parameters, although to a lesser extent when compared with the effects of migration rates. In general, c has a greater effect on E s than p; contours of E s tend to be more horizontal than vertical in all panels of Fig. 2. That is, the temporal relationship between disturbance at the two patches is more influential on their relative elasticities than the probability that disturbance occurs over any given time period.

Although there is only a small amount of variability in E s within a given panel, E s varies dramatically among the four panels (note the log scale). Migration rates appear to affect E s to a much greater extent than disturbance parameters. E s < 1 only when emigration was high from patch 1 and low from patch 2 (Fig. 4d), and in that migration scenario logλ s < 0 for most combinations of p and c. There is a small set of disturbance parameter values (p < 0.05, c ≈ 0) where both logλ s > 0 and E s < 1; this occurs at the lowest values of p, when disturbance is so improbable that results from the stochastic model are comparable to those of the deterministic model (Fig. 2b).

For the reproductive rate and disturbance intensity used for Fig. 4, the stochastic metapopulation growth rate is positive only when the probability of disturbance is low (shaded areas, Fig. 4). The set of disturbance parameters p and c for which logλ s > 0 is largest when on average population 1 is larger than population 2. The set shrinks as individuals become more evenly distributed between the two patches. When population 2 is larger, as in Fig. 4d, logλ s > 0 only for the smallest values of the disturbance probability p.

Two-stage, stochastic model

For many species, especially marine invertebrates, the model of the previous section lacks the appropriate level of demographic detail to adequately summarize the animal’s life history. An example of one such invertebrate is the softshell clam, M. arenaria, a commercially important bivalve commonly found in New England estuaries. M. arenaria’s life cycle is typical of nearshore marine benthic invertebrates (Thorson 1950; Abraham and Dillon 1986). It is characterized by a relatively sedentary adult stage, with adults highly aggregated into patches of suitable habitat. Migration between populations occurs via dispersal of the short-lived larval stage. Like many marine invertebrate species, M. arenaria larvae are produced in vast quantities during a short reproductive season and typically most larvae die before recruiting to the adult phase.

To model such a population requires at least two patches connected by dispersal, and two stages: adults and larvae/juveniles (Fig. 6). We assume that demography, dispersal, and disturbance act sequentially in the intervals (t,t 1), (t 1,t 2) and (t 2, t + 1), respectively, within a given projection interval (t,t + 1).

Between t and t 1, the population undergoes demographic processes. The demographic transitions within population i are given by the matrix B i , with entries composed of adult survival (σ i ), per capita larval production and survival (β i ), and survival and maturation of new recruits (γ i ):

If we define the entries n ij (t) of the vector n(t) to be the number of individuals in stage j of population i at time t and arrange the elements as

then the demographic transitions are described by

where

Next, individuals migrate between patches. Let M j be the matrix of migration rates for individuals in stage j. A simple model for migration has these stage-j individuals migrating from patch i at the per capita rate m ij . Thus,

If we now rearrange the vector n(t 1) as

then

where

Since M. arenaria adults are sedentary, we set M 2 = I. To simplify notation, we will set m 11 = m 1 and m 21 = m 2 from here on.

Finally, disturbance reduces the number of individuals in population i by the proportion D, as described in Eqs. 12–16. If we return to the original arrangement (Eq. 24), we have

where

and

To convert between the vectors n and \(\tilde{\mathbf{n}}\), which is required at each time step, we employ the vec-permutation matrix:

where s is the number of stages, p is the number of patches, and E ij is an s ×p matrix with a 1 in the (i, j) position and zeros elsewhere (Henderson and Searle 1981; for an application see Hunter and Caswell 2005). The vec-permutation matrix has the useful properties

For the two-patch, two-stage case

Combining the demographic, migration, and disturbance processes gives the model

where

Using the matrix calculus approach (Caswell 2007, 2008), we can write the elasticity of λ s to the lower-level parameters as

where \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) is a column vector of parameters, and the operator vec(·) stacks the columns of a matrix on top of each other. The matrix \(\partial \mbox{vec} \mathbf{A}_t / \partial \boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathsf{T}}\) is the derivative of the projection matrix at each time step with respect to each lower-level parameter in θ.

In our model, A t is the product of several matrices, therefore the calculation of \(\partial \mbox{vec} \mathbf{A}_t / \partial \boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathsf{T}}\) is not trivial. Taking the differential of both sides of Eq. 39 gives

Multiplying the first and third terms in Eq. 41 by the identity matrix leaves those terms unchanged.

We can then apply the vec operator to each term in Eq. 42. Using the fact that \( \mbox{vec}(\mathbf{ABC}) = \left(\mathbf{C}^{\mathsf{T}}\otimes\mathbf{A}\right)\mbox{vec}\mathbf{B}\), we obtain an equation for \(d \mbox{vec}\mathbf{A}\) in terms of the component matrices:

Using the chain rule, along with the first identification theorem of Magnus and Neudecker (1985) gives

The matrices \(d\mbox{vec}\mathbb{D}/d\boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathsf{T}}\), \(d\mbox{vec}\mathbb{M}/d\boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathsf{T}}\) and \(d\mbox{vec}\mathbb{B}/d\boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathsf{T}}\) can be rewritten in terms of their component matrices (i.e., D i , M i , and B i ). For example,

where

and E i is the 2 ×2 matrix with every entry zero, save (i,i), which is 1. To calculate \(d\mbox{vec}\mathbb{M}/d\boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathsf{T}}\), simply replace \(\mathbb{D}\) and D i in Eq. 45 by \(\mathbb{M}\) and M i respectively. \(d\mbox{vec}\mathbb{B}/d\boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathsf{T}}\) can be obtained from analogous steps.Footnote 1

We analyzed the model in Eqs. 38 and 39 for σ 1 = 0.9, σ 2 = 0.3, γ 1 = 0.8, γ 2 = 0.24, β 1 = 5.6, and β 2 = 7.5. These parameter values (1) produce individual patch growth rates similar to the net reproductive rates for the one-stage case, i.e., R 1 = 2.5 and R 2 = 0.9; and (2) roughly comport with estimated demographic parameters for M. arenaria from field studies (Ripley and Caswell 2006). First we set migration rates to be equal and low, at m 1 = m 2 = 0.1. Migration rates are difficult to obtain for benthic invertebrates with pelagic larvae, and were not available for M. arenaria, but these values are arguably realistic. We assumed that disturbance affects all patches and stages with intensity D = 0.9, and set the probability of disturbance at the two patches to p = 0.5.

Under these conditions, when the covariance of patch disturbance c is positive, both patches tend to be disturbed simultaneously. This preserves the inherently higher quality of population 1, and the resulting elasticities of logλ s to population 1 parameters (Fig. 7a) are much larger than the elasticities to population 2 parameters (i.e., E s > > 1). When covariance is negative, the patches tend to be disturbed at different times. As a result, population 2 can be temporarily of higher quality than population 1. The elasticities of logλ s to population 2 parameters are therefore larger than when c > 0 (Fig. 7b). Nevertheless elasticities to population 2 parameters are still much smaller than those to population 1 parameters. These results parallel those obtained for the one-stage model (cf. Fig. 4c).

Elasticity of logλ s to changes in lower-level parameters, \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) under two disturbance scenarios: probability of disturbance p is 0.5, with covariance either positive (a) or negative (b). White bars are elasticities in patch 1; gray bars are elasticities in patch 2. In both plots, m 1 = 0.1, m 2 = 0.1, D = 0.9, and logλ s < 0 (–0.27 and –0.23 for (a and b), respectively). The expected proportion of individuals in patch 1 is 0.89 (a) and 0.67 (b)

We also explored the effects of dispersal scenarios that resulted in the majority of the metapopulation density being in patch 1 (m 1 = 0.1, m 2 = 0.9; Fig. 8a) or patch 2 (m 1 = 0.9, m 2 = 0.1; Fig. 8b). The expected proportion of individuals in patch 1 for these two scenarios was 0.88 and 0.23, respectively. We chose a low probability of intense disturbance (p = 0.15, D = 0.9) and no covariance between patches (c = 0). This combination of p and c were chosen to explore the parameter space most likely to yield an interesting result in relative elasticities based on results from the one-stage model. In both dispersal scenarios, logλ s is more elastic to changes in patch 1 parameters than to corresponding parameters in patch 2. When the population in patch 1 is larger than the population in patch 2 (Fig. 8a), elasticities to patch 2 parameters are much smaller than to patch 1. When the majority of individuals are found in patch 2 (Fig. 8b), elasticity to patch 2 parameters are much closer to those of patch 1, but logλ s is still most elastic to patch 1 parameters. In particular, a proportional change in σ 1 still causes a larger proportional change in logλ s than the same change in σ 2.

Elasticity of logλ s to changes in lower-level parameters (\(\boldsymbol{\theta}\)) under two migration scenarios: a m 1 small and m 2 large, resulting in more individuals in patch 1, and b m 1 large and m 2 small, resulting in more individuals in patch 2. White bars are elasticities in patch 1; gray bars are elasticities in patch 2. In both plots, p = 0.15, c = 0, and D = 0.9, and logλ s > 0 (0.53 and 0.05 for (a) and (b) respectively). The expected proportion of individuals in patch 1 is 0.88 (a) and 0.23 (b)

When the model complexity was increased by adding a second stage, the elasticities of stochastic metapopulation growth rate to population 1 parameters increased, while those same elasticities to population 2 parameters decreased. Even when the majority of individuals were in the bad patch, growth rate elasticity was still greatest to parameters in the good patch for the scenarios we examined.

Discussion & conclusions

Good and bad patches, as defined in this paper, are also referred to as “sources” and “sinks”. The source/sink literature (Pulliam 1988; Howe and Davis 1991; Runge et al. 2006) suggests that if one must choose between focusing management efforts on a source or a sink, one should always choose the source. In most cases, our results agree, however we found that under some conditions sink populations are important to long-term metapopulation persistence.

For two patches without demographic structure, the distribution of individuals among patches is important in addition to individual patch growth rates. Improving the source population is best except when the majority of individuals are in the sink population. When most of the individuals are in the sink, changes to parameters in that population affect more individuals and can therefore have a proportionally larger effect on overall metapopulation growth rate.

There is no way to know a priori how likely such patterns are, or the ecological factors that might produce them. The distribution of individuals among patches may account for previous suggestions of the importance of sink populations, for example, higher overall metapopulation size resulting when individuals unable to settle at source populations due to high population densities migrate to sinks (Pulliam 1988) or when emigration from the source patch is suggested to increase population size by offering “insurance” against catastrophe (Levin et al. 1984). This is especially true if the environmental variability is spatially negatively correlated (Wiener and Tuljapurkar 1994).

When conditions are stochastic the correlation of disturbance among patches also influences the relative impacts of the good and bad patch. In cases of positive covariance, disturbance reduces conditions in the good and patches in concert, so results are the same as for the deterministic case. However, when the covariance of disturbance is low, disturbance affecting the good patch can cause the good patch to become worse than the bad patch, so focusing management on the bad patch becomes more important (Figs. 4, 7 and 8).

When demographic structure is considered, the relative importance of the bad patch to overall metapopulation growth rate is reduced. The additional stages act as a buffer for stochastic disturbance and the distribution of individuals is less influential on metapopulation growth rate.

We have focused here on elasticities, which indicate where management efforts should be directed if changes in all parameters of the same magnitude can be made and all else is equal. Other factors also play a role in the implementation of management actions; including cost, feasibility, and inherent parameter variability. Such factors, which can vary both among parameters and among patches, greatly influence the efficacy of management efforts in concert with elasticities. Such constraints can easily be incorporated into a modified metric within the framework of elasticities, and then be used to guide management decisions.

These results offer no rules of thumb for allocating management efforts. Rather, they suggest the importance of conducting elasticity or other perturbation analyses to determine the contributions of individual patches to overall metapopulation growth rate. The analyses presented here can be extended to include additional patches, stages, types of stochasticity, etc. as well as additional constraints on the implementation of management actions.

References

Abraham B, Dillon P (1986) Species profiles: life histories and environmental requirements of coastal fishes and invertebrates (mid-atlantic): softshell clam. USFWS biological report TR EL-82-4, pp 18

Aires-da Silva A, Gallucci V (2007) Demographic and risk analyses applied to management and conservation of the blue shark (Prionace glauca) in the North Atlantic Ocean. Mar Freshw Res 58:570–580

Caswell H (2001) Matrix population models, 2nd edn. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland

Caswell H (2005) Sensitivity analysis of the stochastic growth rate: three extensions. Aust NZ J Stat 47:75–85

Caswell H (2007) Sensitivity analysis of transient population dynamics. Ecol Lett 10:1–15

Caswell H (2008) Perturbation analysis of nonlinear matrix population models. Deomogr Res 18:59–116

Cohen J (1976) Ergodicity of age structure in populations with markovian vital rates, I: countable states. J Am Stat Assoc 71:335–339

Crouse DT, Crowder LB, Caswell H (1987) A stage-based population model for loggerhead sea turtles and implications for conservation. Ecology 68:1412–1423

Enneson JJ, Litzgus JD (2008) Using long-term data and a stage-classified matrix to assess conservation strategies for an endangered turtle (Clemmys guttata). Biol Conserv 141:1560–1568

Furstenberg H, Kesten H (1960) Products of random matrices. Ann Math Stat 31:457–469

Henderson H, Searle S (1981) The vec-permutation, the vec operator and Kronecker products: a review. Linear Multilinear A 9:271–288

Howe R, Davis G (1991) The demographic significance of ‘sink’ populations. Biol Conserv 57:239–255

Hunter C, Caswell H (2005) The use of the vec-permutation matrix in spatial matrix population models. Ecol Model 188:15–21

Kesler DC, Haig SM (2007) Conservation biology for suites of species: demographic modeling for Pacific island kingfishers. Biol Conserv 136:520–530

Levin S, Cohen D, Hastings A (1984) Dispersal strategies in patchy environments. Theor Popul Biol 26:165–191

Magnus JR, Neudecker H (1985) Matrix differential calculus with applications to simple, Hadamard, and Kronecker products. J Math Psychol 29:474–492

Marshall A, Olkin I (1985) A family of bivariate distributions generated by the bivariate bernoulli distribution. J Am Stat Assoc 80:332–338

Parker I (2000) Invasion dynamics of Cytisus scoparius: a matrix model approach. Ecol Appl 10:726–743

Pulliam HR (1988) Sources, sinks, and population regulation. Am Nat 132:652–661

Raithel J, Kauffman M, Pletscher D (2007) Impact of spatial and temporal variation in calf survival on the growth of elk populations. J Wildlife Manag 71:795–803

Ripley B, Caswell H (2006) Recruitment variability and stochastic population growth of the soft-shell clam, Mya arenaria. Ecol Model 193:517–530

Runge J, Runge M, Nichols J (2006) The role of local populations within a landscape context: defining and classifying sources and sinks. Am Nat 167:925–938

Thorson G (1950) Reproductive and larval ecology of marine bottom invertebrates. Biol Rev 25:1–45

Tuljapurkar S (1990) Population dynamics in variable environments. Springer, New York

Tuljapurkar S, Orzack S (1980) Population dynamics in variable environments I. Long-run growth rates and extinction. Theor Popul Biol 18:314–342

Wiener P, Tuljapurkar S (1994) Migration in variable environments: exploring life-history evolution using structured population models. J Theor Biol 166:75–90

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lauren Mullineaux for her insightful comments and contributions to the manuscript. Financial support was provided by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Academic Programs Office; National Science Foundation grants OCE-0326734, OCE-0215905, OCE-0349177, DEB-0235692, DEB-0816514, DMS-0532378, OCE-1031256, and ATM-0428122; and by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Sea Grant College Program Office, Department of Commerce, under Grant No. NA86RG0075 (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Sea Grant Project No. R/0-32), and Grant No. NA16RG2273 (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Sea Grant Project No. R/0-35).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Strasser, C.A., Neubert, M.G., Caswell, H. et al. Contributions of high- and low-quality patches to a metapopulation with stochastic disturbance. Theor Ecol 5, 167–179 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-010-0106-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-010-0106-9