Abstract

Members of the CCN family of matricellular signaling regulators promote cell adhesion through integrins and heparan sulfate-containing proteoglycans. A paradox of the CCN field is that, depending on the set of circumstances examined, individual CCN molecules can have quite different, and often opposing, effects. In a recent report, Franzen and colleagues (Mol Cancer Res. 7:1045–1055, 2009) show using siRNA knockdown that CCN1 (cyr61) is essential for the proliferation of prostate cancer cells. Intriguingly, on the other hand, CCN1 also enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Thus the utility of anti-CCN1 therapy in cancer needs to be carefully considered in light of these divergent results. The significance of this paper is discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

CCN proteins mediate a wide range of biological events, including proliferation, differentiation and migration (Leask and Abraham 2006). Intriguingly, CCN proteins act with often divergent biological consequences; for example, depending on the context, CCN2 (CTGF, connective tissue growth factor) can be either pro- and anti-apoptotic (Frazier et al. 1996; Hishikawa et al. 1999). Adequate explanation of these issues has been controversial.

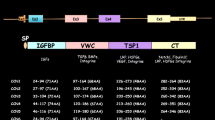

One possible interpretation of the varying effects of the CCN proteins has emerged out of the discovery that the CCN members are matricellular proteins, acting to promote cell adhesion through integrins and heparan sulfate containing proteoglycans (HSPGs) (Lau and Lam 1999). In this model, CCN proteins act on their own as pro-adhesive molecules, and, as a result of their ability to activate adhesive signaling pathways, modify signaling responses of cells to other extracellular ligands (such as growth factors or matrix proteins). As a result, cells respond differently in response to extracellular ligands depending on the constellation of the CCN proteins that are locally available (Perbal 2001).

CCN1 (cyr61) is a potent pro-angiogenic protein that is essential for cardiovascular development during embryogenesis; moreover, its expression in the adult is associated with pathologies involving angiogenesis and inflammation, including play wound healing, atherosclerosis, and tumorigenesis (Babic et al. 1998; Mo et al. 2002; Mo and Lau 2006). In a recent report, Franzen and colleagues (2009) show that, in prostate carcinoma cells, CCN1 can promote cell proliferation while also mediating TRAIL-induced cytotoxicity. CCN1 independently enhanced adhesion of prostate carcinoma cells through α6β1 and α6β4 and HSPGs. Using antisense oligonucleotides, CCN1 knockdown experiments revealed that endogenous CCN1 is critical for proliferation of prostate carcinoma cells. Conversely, whereas CCN1 or a low dose of TRAIL alone did not appreciably affect cell death in normal or cancerous prostate cells, low amounts of TRAIL resulted in cell death when cells were adhered to CCN1- or CCN2-coated surfaces. TRAIL-treated cells adhered to either vitronectin or laminin did not undergo apoptosis. Moreover, prostate carcinoma cells treated with CCN1 antisense oligonucleotides were resistant to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. The authors found that integrins αvβ3 and α6β4 and the HSPG syndecan 4 played critical roles in CCN1/TRAIL cooperation, whereas αvβ5, α5β1, and α6β1 were not important for this process. Thus the integrins involved with TRAIL-mediated apoptosis were somewhat distinct from those required for cell adhesion to CCN1.

Collectively, these findings indicate that the ECM microenvironment, and in particular the presence or absence of CCN proteins, contribute to prostate carcinoma cell growth and survival, with the overall effect of the CCN proteins depending on the presence or absence of different extracellular ligands.

These considerations emphasize on one hand the complexity of the action of CCN proteins, and on the other hand the difficulty of generating appropriate cell based assays to appropriately recapitulate the range of CCN-dependent activities that are observed in vivo. Moreover, these results are important for considering the overall anti-CCN therapies for disease, in that the overall vivo effect of CCN proteins at particular junctures of development, homeostasis and pathologies may differ widely.

References

Babic AM, Kireeva ML, Kolesnikova TV, Lau LF (1998) CYR61, product of a growth factor-inducible immediate-early gene, promotes angiogenesis and tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:6355–6360

Franzen CA, Chen CC, Todorović V, Juric V, Monzon RI, Lau LF (2009) Matrix protein CCN1 is critical for prostate carcinoma cell proliferation and TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Mol Cancer Res 7:1045–1055

Frazier K, Williams S, Kothapalli D, Klapper H, Grotendorst GR (1996) Stimulation of fibroblast cell growth, matrix production, and granulation tissue formation by connective tissue growth factor. J Invest Dermatol 107:404–411

Hishikawa K, Oemar BS, Tanner FC, Nakaki T, Lüscher TF, Fujii T (1999) Connective tissue growth factor induces apoptosis in human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. J Biol Chem 274:37461–37466

Lau LF, Lam SC (1999) The CCN family of angiogenic regulators: the integrin connection. Exp Cell Res 248:44–57

Leask A, Abraham DJ (2006) All in the CCN family: essential matricellular signaling modulators emerge from the bunker. J Cell Sci 119:4803–4810

Mo F-E, Lau LF (2006) The matricellular protein CCN1 is essential for cardiac development. Circ Res 99:961–969

Mo FE, Muntean AG, Chen CC, Stolz DB, Watkins SC, Lau LF (2002) CYR61 (CCN1) is essential for placental development and vascular integrity. Mol Cell Biol 22:8709–8720

Perbal B (2001) NOV (nephroblastoma overexpressed) and the CCN family of genes: structural and functional issues. Mol Pathol 54:57–79

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Leask, A. A sticky situation: CCN1 promotes both proliferation and apoptosis of cancer cells. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 4, 71–72 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12079-009-0079-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12079-009-0079-x