Abstract

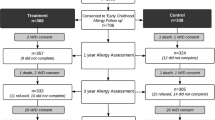

Childhood atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic and recurrent health problem that involves multiple factors, particularly immunological and environmental. We evaluated the impact of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplementation on prenatal arsenic exposure on the risk of atopic dermatitis in preschool children as part of the POSGRAD (Prenatal Omega-3 fatty acid Supplements, GRowth, And Development) clinical trial study in the city of Morelos, Mexico. Our study population included 300 healthy mother–child pairs. Of these, 146 were in the placebo group and 154 in the supplement group. Information on family history, health, and other variables was obtained through standardized questionnaires used during follow-up. Prenatal exposure to arsenic concentrations, which appear in maternal urine, was measured by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry. To assess the effect of prenatal arsenic exposure on AD risk, we ran a generalized estimating equation model for longitudinal data, adjusting for potential confounders, and testing for interaction by omega-3 fatty acid supplementation during pregnancy. The mean and SD (standard deviation) of arsenic concentration during pregnancy was 0.06 mg/L, SD (0.04 mg/L). We found a marginally significant association between prenatal arsenic exposure and AD (OR = 1.12, 95% CI: 0.99, 1.26); however, DHA supplementation during pregnancy modified the effect of arsenic on AD risk (p < 0.05). The results of this study strengthen the evidence that arsenic exposure during pregnancy increases the risk of atopic dermatitis early in life. However, supplementation with omega-e fatty acids during pregnancy could modify this association.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the privacy of individual participants could be compromised but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Odhiambo J et al (2009) Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol 124:1251–8.e23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.009

Thomsen S (2014) Atopic dermatitis: natural history, diagnosis, and treatment. ISRN Allergy 2(2014):354250. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/354250

Leung D, Soter N (2001) Cellular and immunologic mechanisms in atopic dermatitis. Acad Dermatol 44:S1–S12. https://doi.org/10.1067/mjd.2001.109815

Lewis-Jones S (2006) Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. Int J Clin Pract 60:984–992. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01047.x

Pustišek N, Vurnek Živković M, Šitum M (2016) Quality of life in families with children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol 33:28–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.12698

Barraza-Villarreal A, Hernandez-Cadena L, Moreno-Macias H et al (2007) Trends in the prevalence of asthma and other allergic diseases in schoolchildren from Cuernavaca, Mexico. Allergy Asthma Proc 28:368–374. https://doi.org/10.2500/aap.2007.28.2998

JF Stalder A Taïeb DJ Atherton et al (1993) Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: The SCORAD index: Consensus report of the European task force on atopic dermatitis Dermatology 186.https://doi.org/10.1159/000247298

Oranje AP (2011) Practical issues on interpretation of scoring atopic dermatitis: SCORAD Index, objective SCORAD, patient-oriented SCORAD and Three-Item Severity score. Curr Probl Dermatol 41:149–155. https://doi.org/10.1159/000323308

Kantor R, Silverberg JI (2017) Environmental risk factors and their role in the management of atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 13:15–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1744666X.2016.1212660

Schäfer T, Nienhaus A, Vieluf D et al (1998) Prevalence of atopic eczema and body burden of arsenic. Epidemiology 9(S4):S151

Schäfer T, Heinrich J, Wjst M et al (1999) Indoor risk factors for atopic eczema in school children from East Germany. Environ Res 81:151–158. https://doi.org/10.1006/enrs.1999.3964

Ring J, Przybilla B, Ruzicka T (2006) Handbook of atopic eczema. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, New York, Second

Kathuria P, Silverberg JI (2016) Association of pollution and climate with atopic eczema in US children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 27(5):478–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.12543

Romieu I, Torrent M, Garcia-Esteban R et al (2007) Maternal fish intake during pregnancy and atopy and asthma in infancy. Clin Exp Allergy 37:518–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02685.x

Furuhjelm C, Warstedt K, Larsson J et al (2009) Fish oil supplementation in pregnancy and lactation may decrease the risk of infant allergy. Acta Paediatr 98:1461–1467. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01355.x

Lumia M, Luukkainen P, Tapanainen H et al (2011) Dietary fatty acid composition during pregnancy and the risk of asthma in the offspring. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 22:827–835. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01202.x

D’Vaz N, Meldrum SJ, Dunstan JA et al (2012) Postnatal fish oil supplementation in high-risk infants to prevent allergy: randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 130:674–682. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3104

D’Vaz N, Meldrum SJ, Dunstan JA et al (2012) Fish oil supplementation in early infancy modulates developing infant immune responses. ClinExp Allergy 42:1206–1216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04031.x

Lee H-S, Barraza-Villarreal A, Hernandez-Vargas H et al (2013) Modulation of DNA methylation states and infant immune system by dietary supplementation with ω-3 PUFA during pregnancy in an intervention study. Am J Clin Nutri 98:480–487. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.052241

Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Okubo H et al (2013) Maternal fat intake during pregnancy and wheeze and eczema in Japanese infants: the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study. Ann Epidemiol 23:674–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.08.004

Willemsen LEM (2016) Dietary n-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in allergy prevention and asthma treatment. Eur J Pharmacol 785:174–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.03.062

Bisgaard H, Stokholm J, Chawes BL et al (2016) Fish oil-derived fatty acids in pregnancy and wheeze and asthma in offspring. N Engl JMed 375:2530–2539. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1503734

Ramakrishnan U, Stein AD, Parra-Cabrera S et al (2010) Effects of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation during pregnancy on gestational age and size at birth: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Mexico. Food Nutr Bull 31:S108–S116. https://doi.org/10.1177/15648265100312S203

Imhoff-Kunsch B, Stein AD, Villalpando S et al (2011) Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation from mid-pregnancy to parturition influenced breast milk fatty acid concentrations at 1 month postpartum in Mexican Women. J Nutr 141:321–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/15648265100312S203

Hernández E, Barraza-Villarreal A, Escamilla-Núñez MC et al (2013) Prenatal determinants of cord blood total immunoglobulin E levels in Mexican newborns. Allergy Asthma Proc 34:e27-34. https://doi.org/10.2500/aap.2013.34.3688

Oranje AP, Glazenburg EJ, Wolkerstorfer A, de Waard-van der Spek FB (2007) Practical issues on interpretation of scoring atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index, objective SCORAD and the three-item severity score. Br J Dermatol 157:645–648. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08112.x

Gorozave-Car K, Barraza-Villarreal A, Escamilla-Núñez MC et al (2013) Validation of the ISAAC standardized questionnaire used by schoolchildren from Mexicali, Baja California. Mexico Epidemiol Res Inter 2(6760):1–6

Yang C-Y, Chang C-C, Tsai S-S et al (2003) Arsenic in drinking water and adverse pregnancy outcome in an arseniasis-endemic area in northeastern Taiwan. Environ Res 91:29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0013-9351(02)00015-4

Abdul KSM, Jayasinghe SS, Chandana EPS et al (2015) Arsenic and human health effects: a review. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 40:828–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2015.09.016

Liu K-L, Tsai T-L, Tsai W-C et al (2021) Prenatal heavy metal exposure, total immunoglobulin E, trajectory, and atopic diseases: a 15-year follow-up study of a Taiwanese birth cohort. J Dermatol 48:1542–1549. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.16058

Center for Diseases Control and Prevention (2019) Fourth national report on human exposure to environmental chemicals updated tables, January 2019. Atlanta, GA.

Nadeau KC, Li Z, Farzan S et al (2014) In utero arsenic exposure and fetal immune repertoire in a US pregnancy cohort. Clin Immunol 155:188–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2014.09.004

US EPA, “Drinking water standard for arsenic.” p. 2, 2001, Accessed: Aug. 17, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPdf.cgi?Dockey=20001XXC.txt.

WHO (2011) Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality. 4th Edition World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44584/1/9789241548151_eng.pdf

Ashley-Martin J, Levy AR, Arbuckle TE et al (2015) Maternal exposure to metals and persistent pollutants and cord blood immune system biomarkers. Environ Health 14:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-015-0046-3

Farzan SF, Karagas MR, Chen Y (2013) In utero and early life arsenic exposure in relation to long-term health and disease. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 272:384–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2013.06.030

Cardenas A, Houseman EA, Baccarelli AA et al (2015) In utero arsenic exposure and epigenome-wide associations in placenta, umbilical artery, and human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Epigenetics 10:1054–1063. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592294.2015.1105424

Perera F, Herbstman J (2011) Prenatal environmental exposures, epigenetics, and disease. Reproduc Toxicol 31:363–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.12.055

Engström K, Wojdacz TK, Marabita F et al (2017) Transcriptomics and methylomics of CD4-positive T cells in arsenic-exposed women. Arch Toxicol 91:2067–2078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-016-1879-4

DaVeiga SP (2012) Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis: a review. Allergy Asthma Proc 33:227–234. https://doi.org/10.2500/aap.2012.33.3569

Escamilla-Nuñez MC, Barraza-Villarreal A, Hernández-Cadena L et al (2014) Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation during pregnancy and respiratory symptoms in children. Chest 146:373–382

Türkez H, Geyikoglu F, Yousef MI (2012) Ameliorative effect of docosahexaenoic acid on 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced histological changes, oxidative stress, and DNA damage in rat liver. Toxicol Ind Health 28:687–696. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748233711420475

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to the participants in this project.

Funding

This study was supported by Mexico’s National Council of Science and Technology (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, CONACYT), Grant 87121, and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Award R01HD058818.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CEN was the general coordinator and participated in conceptualization; methodology; validation; formal analysis; investigation; writing, original draft; writing, review and editing; visualization; and supervision. IFG: Conceptualization; methodology; data curation; writing, original draft; visualization. ABV: Methodology; investigation; writing, original draft; resources; supervision; writing, review and editing; project administration. LHC: Writing, original draft; writing, review and editing. ENOP: Writing, original draft; writing, review and editing. IR: Writing, original draft; writing, review and editing; funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were under the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Ethics and Investigation Committees of the Mexican National Institute of Public Health (Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, INSP), and the Emory University Ethics Committee approved the investigation protocol (CI:418).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All children participated in the study with their parent’s written informed consent.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Figueroa-Garduño, I., Escamilla-Núñez, C., Barraza-Villarreal, A. et al. Docosahexaenoic Acid Effect on Prenatal Exposure to Arsenic and Atopic Dermatitis in Mexican Preschoolers. Biol Trace Elem Res 201, 3152–3161 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-022-03411-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-022-03411-3