Abstract

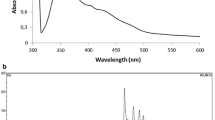

Astaxanthin and β-carotene are the most prominent carotenoids extensively used in pharmaceutics. Here, we present a halotolerant bacterium from Lake Wadi El-Natrun capable of producing astaxanthin and β-carotene analyzed by HPLC, ESI–MS, and infrared spectroscopy. The phenotypic and phylogenetic analyses classified the isolate as a novel strain of the genus Planococcus, for which the name Planococcus sp. Eg-Natrun is proposed. Carotenoid biosynthesis can exceptionally occur in a light-inducible or constitutive manner. The maximum carotenoid yields were 610 ± 13 µg/g (~ 38% β-carotene and ~ 21% astaxanthin) in a minimal medium with acetate and 1024 ± 53 µg/g dry cells in a rich marine medium. The carotenogenesis incentives (e.g., acetate) and disincentives (e.g., methomyl) were discussed. Moreover, we successfully isolated the CrtE gene, one of the astaxanthin biosynthesis genes, from the unknown genome using a consensus-based degenerate PCR approach. To our knowledge, this is the first report elucidating astaxanthin and β-carotene in the genus Planococcus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

DNA sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in GenBank with the accession codes: “EU825769” and “EU854450” for the 16S ribosomal RNA gene and GGPP synthase-encoding gene (CrtE), respectively. Other data generated or analyzed within this study are included in this published article.

References

Hage-Hülsmann, J., Klaus, O., Linke, K., et al. (2021). Production of C20, C30 and C40 terpenes in the engineered phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus. Journal of Biotechnology, 338, 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBIOTEC.2021.07.002

Reichenbach, H., & Kleinig, H. (1971). The carotenoids of Myxococcus fulvus (Myxobacterales). Archiv für Mikrobiologie, 76(4), 364–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00408532

Davies, B. H., & Taylor, R. F. (1976). Carotenoid biosynthesis—The early steps. Carotenoids, 4, 211–221.

Robledo, J. A., Murillo, A. M., & Rouzaud, F. (2011). Physiological role and potential clinical interest of mycobacterial pigments. IUBMB Life, 63(2), 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/IUB.424

Ambati, R. R., Gogisetty, D., & Aswathanarayana, R. G., et al. (2018). Industrial potential of carotenoid pigments from microalgae: Current trends and future prospects. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 1–22.

Osganian, S. K., Stampfer, M. J., Rimm, E., et al. (2003). Dietary carotenoids and risk of coronary artery disease in women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 77(6), 1390–1399.

Fouad, M. A., Sayed-Ahmed, M. M., Huwait, E. A., et al. (2021). Epigenetic immunomodulatory effect of eugenol and astaxanthin on doxorubicin cytotoxicity in hormonal positive breast cancer cells. BMC Pharmacology and Toxicology, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40360-021-00473-2/FIGURES/7

Zhang, C., Chen, X., & Too, H. P. (2020). Microbial astaxanthin biosynthesis: Recent achievements, challenges, and commercialization outlook. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 104(13), 5725–5737. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00253-020-10648-2

de la Fuente, J. L., Rodríguez-Sáiz, M., Schleissner, C., et al. (2010). High-titer production of astaxanthin by the semi-industrial fermentation of Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Journal of Biotechnology, 148(2–3), 144–146.

Calo, P., de Miguel, T., Sieiro, C., et al. (1995). Ketocarotenoids in halobacteria: 3-hydroxy-echinenone and trans-astaxanthin. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 79(3), 282–285.

Ide, T., Hoya, M., Tanaka, T., & Harayama, S. (2012). Enhanced production of astaxanthin in Paracoccus sp. strain N-81106 by using random mutagenesis and genetic engineering. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 65, 37–43.

Asker, D. (2017). Isolation and characterization of a novel, highly selective astaxanthin-producing marine bacterium. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 65(41), 9101–9109. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.JAFC.7B03556

Liu, H., Zhang, C., Zhang, X., et al. (2020). A novel carotenoids-producing marine bacterium from noble scallop Chlamys nobilis and antioxidant activities of its carotenoid compositions. Food Chemistry, 320, 126629. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2020.126629

Yokoyama, A., Izumida, H., & Shizuri, Y. (1996). New carotenoid sulfates isolated from a marine bacterium. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 60(11), 1877–1878.

Armstrong, G. A. (2003). Genetics of Eubacterial Carotenoid Biosynthesis: A Colorful Tale, 51, 629–659. https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV.MICRO.51.1.629

Shindo, K., Endo, M., Miyake, Y., et al. (2008). Methyl glucosyl-3,4-dehydro-apo-8′-lycopenoate, a novel antioxidative glyco-c30-carotenoic acid produced by a marine bacterium Planococcus maritimus. The Journal of Antibiotics, 61(12), 729–735. https://doi.org/10.1038/ja.2008.86

Lee, J. H., Kim, J. W., & Lee, P. C. (2020). Genome mining reveals two missing CrtP and AldH enzymes in the C30 carotenoid biosynthesis pathway in Planococcus faecalis AJ003T. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 25(24). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25245892

Takemura, M., Takagi, C., Aikawa, M., et al. (2021). Heterologous production of novel and rare C30-carotenoids using Planococcus carotenoid biosynthesis genes. Microbial Cell Factories, 20(1), 194. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-021-01683-3

Majumdar, S., Mandal, T., & Dasgupta Mandal, D. (2020). Production kinetics of β-carotene from Planococcus sp. TRC1 with concomitant bioconversion of industrial solid waste into crystalline cellulose rich biomass. Process Biochemistry, 92, 202–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PROCBIO.2020.01.012

Summerfield, M. (1975). An investigation into the membrane composition of a Planococcus species. University of St.

Sneath, P. H. A., Mair, N. S., Sharpe, M. E., et al. (1986). Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Volume 2. Williams & Wilkins.

Larkin, M. A., Blackshields, G., Brown, N. P., et al. (2007). Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics, 23(21), 2947–2948. https://doi.org/10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTM404

Zapata-Vélez, A. M., & Trujillo-Roldán, M. A. (2010). The lack of a nitrogen source and/or the C/N ratio affects the molecular weight of alginate and its productivity in submerged cultures of Azotobacter vinelandii. Annals of Microbiology, 60(4), 661–668. https://doi.org/10.1007/S13213-010-0111-7/FIGURES/3

Batra, G., Gortzi, O., Lalas, S. I., et al. (2017). Enhanced antioxidant activity of Capsicum annuum L. and Moringa oleifera L. extracts after encapsulation in microemulsions. Chemical Engineering, 1(2), 15.

Polyakov, N. E., Leshina, T. V., Konovalova, T. A., et al. (2001). Carotenoids as scavengers of free radicals in a fenton reaction: Antioxidants or pro-oxidants? Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 31(3), 398–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00598-6

Polyakov, N. E., Kruppa, A. I., Leshina, T. V., et al. (2001). Carotenoids as antioxidants: Spin trapping EPR andoptical study. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 31(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00547-0

Rose, T. M. (2005). CODEHOP-mediated PCR - A powerful technique for the identification and characterization of viral genomes. Virology Journal, 2(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-2-20/FIGURES/18

Gupta, R. S., & Patel, S. (2020). Robust demarcation of the family Caryophanaceae (Planococcaceae) and its different genera including three novel genera based on phylogenomics and highly specific molecular signatures. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, 2821. https://doi.org/10.3389/FMICB.2019.02821/BIBTEX

Vila, E., Hornero-Méndez, D., Azziz, G., et al. (2019). Carotenoids from heterotrophic bacteria isolated from Fildes Peninsula, King George Island, Antarctica. Biotechnology Reports, 21.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.btre.2019.e00306

Sumi, S., Suzuki, Y., Matsuki, T., et al. (2019). Light-inducible carotenoid production controlled by a MarR-type regulator in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49384-7

Rinalducci, S., Pedersen, J. Z., & Zolla, L. (2008). Generation of reactive oxygen species upon strong visible light irradiation of isolated phycobilisomes from Synechocystis PCC 6803. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics, 1777(5), 417–424.

Takano, H., Mise, K., Hagiwara, K., et al. (2015). Role and function of LitR, an adenosyl B12-bound light-sensitive regulator of Bacillus megaterium QM B1551, in regulation of carotenoid production. Journal of Bacteriology, 197(14), 2301–2315. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.02528-14

Engelhardt, M. A., Daly, K., Swannell, R. P. J., et al. (2001). Isolation and characterization of a novel hydrocarbon-degrading, Gram-positive bacterium, isolated from intertidal beach sediment, and description of Planococcus alkanoclasticus sp. nov. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 90(2), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.1365-2672.2001.01241.X

Li, Y., Gong, F., Guo, S., et al. (2021). Adonis amurensis is a promising alternative to Haematococcus as a resource for natural esterified (3S,3′S)-astaxanthin production. Plants, 10(6), 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/PLANTS10061059

López, G.-D., Álvarez-Rivera, G., Carazzone, C., et al. (2021). Carotenoids in bacteria: Biosynthesis, extraction, characterization and applications. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202108.0383.v1

Jing, K., He, S., Chen, T., et al. (2016). Enhancing beta-carotene biosynthesis and gene transcriptional regulation in Blakeslea trispora with sodium acetate. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 114, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BEJ.2016.06.015

Kobayashi, M., Kakizono, T., & Nagai, S. (1993). Enhanced carotenoid biosynthesis by oxidative stress in acetate-induced cyst cells of a green unicellular alga. Haematococcus pluvialis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 59(3), 867–873. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.59.3.867-873.1993

Theimer, R. R., & Rau, W. (1970). Untersuchungen über die lichtabhängige Carotinoidsynthese. Planta, 92(2), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00385205

Polyakov, N. E., Magyar, A., & Kispert, L. D. (2013). Photochemical and optical properties of water-soluble xanthophyll antioxidants: Aggregation vs complexation. Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 117(35), 10173–10182. https://doi.org/10.1021/JP4062708/ASSET/IMAGES/MEDIUM/JP-2013-062708_0012.GIF

Ozhogina, O. A., & Kasaikina, O. T. (1995). β-carotene as an interceptor of free radicals. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 19(5), 575–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/0891-5849(95)00064-5

Volkov, D. S., Krivoshein, P. K., & Proskurnin, M. A. (2020). Detonation nanodiamonds: A comparison study by photoacoustic, diffuse reflectance, and attenuated total reflection FTIR spectroscopies. Nanomaterials, 10(12), 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/NANO10122501

Berezin, K. V., & Nechaev, V. V. (2005). Calculation of the IR spectrum and the molecular structure of β-carotene. Journal of Applied Spectroscopy, 72(2), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10812-005-0049-X

Van Breemen, R. B., Dong, L., & Pajkovic, N. D. (2012). Atmospheric pressure chemical ionization tandem mass spectrometry of carotenoids. International journal of mass spectrometry, 312, 163. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJMS.2011.07.030

Ohki, S., Miller-Sulger, R., Wakabayashi, K., et al. (2003). Phytoene desaturase inhibition by O-(2-Phenoxy)ethyl-N-aralkylcarbamates. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 51(10), 3049–3055. https://doi.org/10.1021/JF0262413

Xu, Y., & Harvey, P. J. (2020). Phytoene and phytofluene overproduction by Dunaliella salina using the mitosis inhibitor chlorpropham. Algal Research, 52, 102126. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ALGAL.2020.102126

Waghmode, S., Suryavanshi, M., Sharma, D., et al. (2020). Planococcus species – An imminent resource to explore biosurfactant and bioactive metabolites for industrial applications. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 8(August), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2020.00996

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Cairo University’s internal funding. The authors thank Prof. Sayed Gouda (University of Derby) for insightful discussions regarding selecting the origin of the isolate. The authors acknowledge the support from the Biochemical & Genetic Analysis Unit (National Research Center, Egypt) for HPLC/ESI-MS analysis and the Microbiology Unit (Micro Analytical Center, Cairo University) for performing the phenotypic characterization of the isolate.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. S. and M. S. M. designed the experiments. A. S. performed the research work and the data analysis. M. S. M. supervised the research. A. S. wrote the paper. A. S. and I. E. polished the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The study does not involve experiments on humans or animals. Therefore, the ethical approval is not required.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sayed, A., Elbalasy, I. & Mohamed, M.S. Novel β-Carotene and Astaxanthin-Producing Marine Planococcus sp.: Insights into Carotenogenesis Regulation and Genetic Aspects. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 195, 217–235 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-022-04148-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-022-04148-4