Abstract

Background

In total joint arthroplasty (TJA), vancomycin is used as perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with penicillin allergy or in patients colonized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Although vancomycin dosing should be weight-based (15 mg/kg), not all surgeons are aware of this; a fixed 1-g dose is instead frequently administered.

Questions/purposes

(1) Is there a difference in the risk of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) in patients receiving vancomycin or cefazolin prophylaxis after primary TJA? (2) What proportion of patients is adequately dosed with vancomycin? (3) Compared with actual fixed dosing, does weight-based dosing result in a greater proportion of patients staying above the recommended 15-mg/L level at the beginning and end of surgery? (4) Are patients overdosed with vancomycin at greater risk of developing nephrotoxicity and acute kidney injury?

Methods

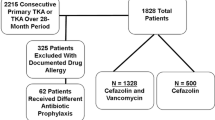

A single-institution, retrospective study was performed on 1828 patients undergoing primary TJAs who received vancomycin prophylaxis between 2008 and 2014. During the same period, 5810 patients underwent primary TJA and received cefazolin monotherapy. A chart review was performed to obtain patient characteristics, antibiotic dose and timing of administration, and microbiology data. Adequate vancomycin dosing was defined as 15 mg/kg and within the 125-mg range. Vancomycin levels were calculated at the beginning and end of surgery using pharmacokinetic equations. Levels of 15 mg/L were considered adequate. Logistic regression, chi square tests, and analysis of variance were performed.

Results

Among primary TJAs, patients receiving vancomycin had a higher rate of PJI (32 of 1828 [2%]) compared with patients receiving cefazolin prophylaxis (62 of 5810 [1%]; adjusted odds ratio, 1.587 [1.004–2.508]; p = 0.048). Ten percent of PJIs in the vancomycin underdosed group (two of 20) was caused by MRSA, and no patients with adequate dosing or overdosing of vancomycin developed PJI with MRSA. Of all procedures in which vancomycin monotherapy was used, 28% (518 of 1828) was adequately dosed according to weight-based dosage recommendations. Furthermore, 94% (1726 of 1828) of patients received a fixed 1-g dose of vancomycin, of whom 64% (1105 of 1726) were underdosed. All patients had vancomycin infusion initiated within 2 hours before incision. A weight-based protocol would have resulted in fewer patients having unacceptably low vancomycin levels (< 15 mg/L) compared with those with actual fixed dosing, both for the beginning of surgery at the time of incision (zero of 1828 [0%] versus 471 of 1828 [26%]; odds ratio, 0.001 [0.000–0.013]; p < 0.001) and at the end of surgery (33 of 1828 [2%] versus 746 of 1828 [41%]; odds ratio, 0.027 [0.019–0.038]; p < 0.001). Between the vancomycin dosage groups, there were no differences in the rate of nephrotoxicity (underdosed: 12 of 1130 [1%], adequately dosed: five of 518 [1%], overdosed: four of 180 [2%], p = 0.363) and acute kidney injury (underdosed: 28 of 1130 [2%], adequately dosed: 10 of 518 [2%], overdosed: six of 180 [3%], p = 0.561).

Conclusions

The majority of patients given vancomycin prophylaxis are underdosed according to the weight-based dosage recommendations, and MRSA did not occur in patients who were adequately dosed with vancomycin. Surgeons should thus ensure that their patients are adequately dosed with vancomycin using the recommendation of 15 mg/kg and that the dose of vancomycin is administered in a timely fashion. Furthermore, and based on the findings of this study, we have moved toward limiting the utilization of vancomycin prophylaxis for patients undergoing elective arthroplasty at our institution.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Administration of perioperative prophylaxis is believed to be one of the most important strategies for prevention of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) [1, 27]. The most appropriate perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty (TJA) is a first- or second-generation cephalosporin or penicillin [12]. However, in patients with penicillin allergy, first- and second-generation cephalosporins are often avoided because of a potential for crossreactivity. In these patients vancomycin and clindamycin are used as alternative perioperative prophylaxis. Furthermore, vancomycin is the preferred antibiotic for patients who are proven or potential carriers of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [12].

The majority of antibiotics administered to patients undergoing surgery needs to be administered based on a weight-based dose [18, 19]. The goal of dosing is to achieve a safe and effective tissue concentration of drug that sufficiently exceeds the concentration needed to inhibit the growth of most colonizing skin flora at the time of surgical incision [24]. The current recommendation for vancomycin is a dose of 15 mg/kg [4, 14]. Because of the increasing prevalence of obesity in the United States [11], coupled with the increasing resistance of MRSA (increasing minimum inhibitory concentration) to vancomycin [17], and the lack of awareness of surgeons regarding weight-based administration, it is believed that the majority of patients undergoing elective arthroplasty may be inadequately dosed. Adequate dosing of perioperative antibiotics becomes more pertinent in overweight and obese patients, who are more prone to be underdosed and are at a higher risk for PJI in the first instance [18, 25]. Although antibiotic underdosing can theoretically result in a higher rate of infection as a result of inadequate serum and tissue levels of the antibiotic, overdosing is also an issue because it carries the potential for drug toxicity [5, 16, 23, 29].

As far as we are aware, the issue of dosing of vancomycin in patients undergoing TJA has not been explored. This study was set up to determine the incidence of PJI in patients undergoing TJA who received cefazolin only versus those who received vancomycin only as the perioperative prophylaxis. Although it is known that vancomycin does not have coverage against Gram-negative organisms [12, 30] and has been shown to have a higher risk of surgical site infections [21, 30], it is unknown whether patients who receive vancomycin as their sole prophylactic agent have a higher rate of PJI compared with those receiving cefazolin.

We therefore asked: (1) Is there a difference in the risk of PJI in patients receiving vancomycin or cefazolin prophylaxis after primary TJA? (2) What proportion of patients is adequately dosed with vancomycin? (3) Compared with actual fixed dosing, does weight-based dosing result in a greater proportion of patients staying above the recommended 15-mg/L level at the beginning and end of surgery? (4) Are patients overdosed with vancomycin at greater risk of developing nephrotoxicity and acute kidney injury?

Materials and Methods

A retrospective study was performed at a single institution on patients undergoing primary TJA between 2006 and 2014. Our joint arthroplasty that was set up in 2000 contains 30,597 patients undergoing primary TJA. However, information on antibiotic prophylaxis is not available on 10,952 patients who received their surgery before 2005 and were excluded leaving 19,645 patients. We then excluded 15,850 patients for having nonvancomycin antibiotics administered, leaving 3795 patients. We excluded 1948 patients who did not receive monotherapy vancomycin, leaving 1847 patients in our final cohort. We further excluded 19 patients who were missing various demographic data to calculate pharmacokinetic information. The final cohort consisted of 1828 patients who received vancomycin monotherapy for perioperative prophylaxis and underwent 958 THAs (52%) and 870 TKAs (48%). There were 1222 women (67%) and 606 men (33%) with an average body mass index of 30 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2, respectively. Among the patients receiving vancomycin, 78.3% (1431 of 1828), received vancomycin for a penicillin allergy or intolerance and the remainder received vancomycin because of having a history of MRSA infections or potentially being a MRSA carrier such as those from nursing homes and healthcare workers. In patients with a reported allergy or intolerance to penicillin, vancomycin was used regardless of the severity and nature of the prior reaction and subsequent likelihood of developing a true anaphylactic reaction. Patients receiving multiple joint replacements at different time points were included on each occasion. The dose and time of administration of vancomycin in these patients were extracted using our electronic medical records that are completed by the anesthesia team for every patient. Our institutional protocol is to administer vancomycin over 1 to 2 hours of infusion, aiming to initiate administration before skin incision. Staphylococcus aureus screening and decolonization were not routinely performed during the study period.

Using the revised dosing protocol of 15 mg/kg of body weight for vancomycin, proper dosage was calculated for each patient. These values were then compared with the dose given to the patients at the time of surgery. All calculated total doses were rounded to the closest 250 mg. Patients were stratified using the weight-based dosing protocol (15 mg/kg) into the following categories: adequately dosed (administered dose of 15 mg/kg ± 125-mg range), underdosed (< 15 mg/kg − 125 mg), or overdosed (greater than the sum of 15 mg/kg + 125 mg).

An electronic query and chart review were performed to obtain the dose and the time of administration of vancomycin to each patient, microbiology data, joint involved including laterality, body mass index (BMI), operative time, time to incision from administration of vancomycin, Charlson comorbidities [10], and complications including PJI and drug toxicity. Patients’ gender, height, weight, and serum creatinine were utilized in the pharmacokinetic analysis. Patients with PJI were determined from a crossreference of a prospectively maintained institutional PJI database at our institution. This was followed by manual chart review to confirm PJI based on the Musculoskeletal Infection Society criteria [20]. We defined PJI in patients who received multiple joint arthroplasties as the same joint that was infected. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes were electronically queried for nephrotoxicity (583.9, 583.89, 580.9, 580.89, 580.4, 584.*), ototoxicity (960.8, 388.2, 963.1), and allergic reaction (995.3, 995.27). Acute kidney injury was defined as an elevation in creatinine by 50%. The number of postoperative creatinine values available was 3658 (mean of 2.001 values per patient).

We calculated expected vancomycin levels in blood based on pharmacokinetic equations (Table 1) for both the actual dose given and the hypothetical weight-based dose with the goal of achieving the recommended 15-mg/L serum level. For the entire vancomycin cohort of primary and revision TJAs, the mean vancomycin dose, clearance, and half-life were 1.02 g, 5.35 L/h, and 8.64 hours, respectively. The mean time for starting vancomycin before incision was 35 minutes.

To serve as a concurrent control for the vancomycin group, the PJI rate among patients undergoing primary TJAs who received cefazolin monotherapy was obtained from the same time period. This was also performed by querying the electronic medical record for patients who underwent primary TJA who were administered cefazolin monoprophylaxis. There were 5810 patients who received cefazolin monotherapy during the same period. All patients receiving cefazolin monoprophylaxis received a dose of 2 g of the antibiotic based on a long-established protocol at our institution.

All statistical analyses were performed with MedCalc Statistical Software Version 14.8.1 (Ostend, Belgium). Differences between cefazolin and vancomycin groups were analyzed with chi-square analysis as well as logistic regression analysis to account for confounders. Differences among the three vancomycin dose cohorts were assessed using chi-square analyses and three-way analysis of variance. An α level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

Among primary TJAs, patients receiving vancomycin had a higher rate of PJI (32 of 1828 [2%]) compared with patients receiving cefazolin prophylaxis (62 of 5810 [1%]; odds ratio, 1.65 [1.07–2.54]; p = 0.02). When adjusting for comorbidities, age, sex, joint, and BMI through a logistic regression analysis, we found that there was still a difference in the PJI rate between patients receiving vancomycin and those receiving cefazolin antibiotic prophylaxis (odds ratio, 1.587 [1.004–2.508]; p = 0.04; Table 2). The evaluation of organism profile causing PJI between the groups revealed that 20 of 32 PJIs (63%) in patients who received vancomycin monoprophylaxis were Gram-positive versus 43 of 62 PJIs (69%) in patients receiving cefazolin monotherapy (p = 0.504). When stratifying based on vancomycin dosage, there was no difference in PJI rate (underdosed: 20 of 1130 [2%], adequately dosed: nine of 518 [2%], and overdosed: three of 180 [2%], p = 0.995; Table 3). Of the 20 PJIs in the underdosed cohort, two (10%) were the result of MRSA; none of the PJIs in the adequately dosed vancomycin group or overdosed vancomycin group was the result of methicillin-resistant organisms. Of the two cases in the underdosed group that were caused by MRSA, one patient had a remote history of MRSA infection and the other had a penicillin allergy as the reasons for receiving vancomycin prophylaxis.

Of the 1828 procedures in which vancomycin monotherapy was used (958 hips and 870 knees), 1130 (62%) were underdosed, 518 (28%) were adequately dosed, and 180 (10%) were overdosed according to the weight-based dosage recommendation from recent clinical guidelines. Furthermore, 1726 of 1828 (94%) patients receiving vancomycin were given a fixed 1-g dose with 1105 of 1726 (64%) of those patients being underdosed. Patients who were underdosed had higher BMIs (33 ± 5 kg/m2) compared with those adequately dosed (26 ± 4 kg/m2), and patients overdosed had lower BMIs (23 ± 5 kg/m2, p < 0.001; Table 4). A weight-based protocol would have resulted in fewer patients having unacceptably low vancomycin levels (< 15 mg/L) compared with those with actual fixed dosing, both for the beginning of surgery at the time of incision (zero of 1828 [0%] versus 471 of 1828 [26%]; odds ratio, 0.001 [0.000–0.013]; p < 0.001) and at the end of surgery (33 of 1828 [2%] versus 746 of 1828 [41%]; odds ratio, 0.027 [0.019–0.038]; p < 0.001). The average time taken for the vancomycin level to drop < 15 mg/kg was 3 hours (Fig. 1).

The vancomycin level drops below 15 mg/ L at 3 hours after administration of vancomycin. Used with permission from Catanzano A, Phillips M, Dubrovskaya Y, Hutzler L, Bosco J. The standard one gram dose of vancomycin is not adequate prophylaxis for MRSA. Reprinted with permission by University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics from Catanzano et al. [9].

Between the vancomycin dosage groups, there were no differences in the rate of nephrotoxicity (underdosed: 12 of 1130 [1%], adequately dosed: five of 518 [1%], overdosed: four of 180 [2%], p = 0.363) and acute kidney injury (underdosed: 28 of 1130 [2%], adequately dosed: 10 of 518 [2%], overdosed: six of 180 [3%], p = 0.561; Table 3).

There were no instances of ototoxicity and two patients who experienced allergic reactions in the entire cohort.

Discussion

Vancomycin often is used as an alternative antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with penicillin allergy because of the fear of crossreactivity with cephalosporins. In addition, vancomycin may be given to patients with confirmed or suspected MRSA carriage. Although traditionally 1 g vancomycin was considered to be adequate prophylaxis, recent clinical guidelines recommend that administration of vancomycin should be weight-based with 15 mg/kg as the appropriate dose [2, 7]. This study was specifically conceived to examine the rate of compliance with the latter recommendation.

The findings of this study should be examined in light of some limitations that existed. The most salient of these limitations is that although our sample size is relatively high, we were likely underpowered to evaluate events with a low rate such as PJI and ototoxicity among the three vancomycin dosing groups. Additionally, this study is retrospective in nature and thus is subject to inherent biases. Furthermore, the detection of complications such as ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity primarily relied on ICD-9 codes, being prone to coding errors. For the acute kidney injury metric, we had an average of two postoperative creatinine values per patient because length of stay is often 1 to 2 days postoperatively for a TJA at our institution; thus, an acute kidney injury may have been missed if it occurred outside of the hospital stay. However, our prospective database on patients undergoing TJA contains data on readmissions of patients for any reason and we are confident that not many, if any, patients with acute kidney injury were missed in this study. In addition, vancomycin toxicity occurs within a few days of administration [22, 32] and we believe patients with acute kidney injury would have had a longer hospital stay. The rate of vancomycin nephrotoxicity in this cohort was low because the majority of the patients in the study were underdosed. Additionally, the three dosing cohorts were different in terms of their demographics; we could not control for BMI among these cohorts because this is an inherent limitation in this study. This is because the majority of surgeons used fixed dosing and administered 1 g vancomycin; thus, the categorization of patients into the three dosing groups is dependent on their weight. Lastly, it should be noted that as a result of the large sample size evaluated to assess a relatively infrequent endpoint, we do not have followup information and it is thus plausible that the followup of both cohorts is different. Although this may influence the results of this study, there have been no institutional differences during the course of the study that affect which patients are to receive vancomycin versus cefazolin.

To date, this is the first study to directly compare and demonstrate a difference in PJI rate between patients receiving vancomycin-only and cefazolin-only prophylaxis, even after adjusting for confounding variables. The prior literature contains conflicting results when comparing the two groups and has mainly focused on surgical site infections (SSIs) rather than PJI. In a study of 18,830 primary TJAs utilizing the Veterans Affairs database, Ponce et al. [21] found that the SSI rate was higher in patients who received vancomycin as the sole prophylactic agent compared with cefazolin (2.6% versus 1.3%). The main reason for this observation is that unlike cephalosporins, which have some Gram-negative coverage, vancomycin has no coverage against Gram-negative organisms [12, 30]. One study by Tan et al. [30] demonstrated that administration of vancomycin as a sole agent for patients undergoing TJA resulted in a higher rate of Gram-negative deep SSI (odds ratio, 2.42), perhaps highlighting the issue regarding lack of coverage against some pathogens. Another study by Tyllianakis et al. [31] demonstrated no difference in the SSI rate between patients receiving cefuroxime (six of 188) and those receiving vancomycin (six of 129) in a prospective randomized study. Sewick et al. [26] compared dual antibiotics (vancomycin and cefazolin) with cefazolin monotherapy and found no difference in the SSI rate (1.1% versus 1.4%, p = 0.64). Furthermore, a study by Smith et al. [28] reviewed a series of 5036 primary TJAs and found that transitioning from cefazolin to vancomycin resulted in a reduction of PJI from 1% to 0.5%; however, unlike our study, the authors of the last study did not conduct a multivariate analysis to account for patient factors such as comorbidities and also for other infection prevention strategies that they had implemented at the same time period. Nearly two-thirds of the patients at our institution did not receive the recommended weight-based dose of vancomycin when undergoing TJA. Although the rate of PJI was not different among the three vancomycin dose groups, we found that both PJIs developed in the underdosed group were caused by MRSA. None of the patients with adequate dosing developed PJI by MRSA. The issue of underdosing becomes even more important when one considers the fact that the majority of patients not receiving an adequate dose of vancomycin were obese and those overdosed were likely to be underweight patients. Obese patients are at higher risk of PJI in the first instance [15, 25] and depriving them of adequate perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis may have an additional adverse effect on the rate of PJI. It is also possible that the signal of increased PJI observed in obese patients may in part be a result of inadequate perioperative antibiotics.

When examining the hypothetical scenario of weight-based dosing, vancomycin levels at the time of incision and at the end of the procedure were much more likely to be higher than the recommended 15 mg/L compared with the actual doses that the patients were given in this cohort. Catanzano et al. demonstrated a similar disparity between weight-based dosing and actual dosing of vancomycin in which the calculated vancomycin level at the end of procedure was < 15 mg/L in 60% of patients with a 1-g dose compared with 12% with a weight-based dose [9]. Thus, if weight-based dosing was implemented, we would expect adequate serum levels of vancomycin throughout surgery from incision to closure.

This study did not find a difference in the known adverse effects of vancomycin, namely ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity. Nephrotoxicity (assessed by ICD-9 codes) and acute kidney injury (based on serum creatinine level elevations) were infrequent events throughout all dosing groups.

The collective findings of this study as well as prior studies bring to life the issue that true challenges exist when vancomycin is used as the sole perioperative prophylaxis. It is our belief that administration of vancomycin as a perioperative prophylaxis should be seriously limited. The International Consensus on PJI recommends that patients with nonanaphylactic penicillin allergy can safely receive a first- or second-generation cefazolin [12]. The relatively high rate of crossreactivity of cephalosporins with penicillins that traditionally was believed to be approximately 10% has been questioned recently with multiple studies estimating that up to 90% of patients reporting an allergy are actually able to tolerate penicillin and its derivatives; thus, true crossreactivity has been demonstrated to be as low as 1% [6, 8, 13]. Some authorities believe that cephalosporins can be given to those with anaphylactic penicillin allergy safely in a controlled environment like the operating room [3]. If the latter is not deemed to be appropriate, surgeons electing to administer perioperative vancomycin to patients undergoing TJA should consider the addition of a second agent such as aminoglycosides to supplement the coverage against Gram-negative and other pathogens.

Underdosing of vancomycin is common and more attention to the weight-based dosing of the drug should be given. The latter is especially pertinent because the rate of PJI is higher in patients receiving vancomycin compared with those receiving cefazolin. The findings of the study have provided an impetus for us to limit the use of vancomycin as the sole prophylaxis in patients undergoing TJA. We now administer cephalosporins to the majority of patients with penicillin allergy and have not so far noted any serious crossreactivity issues. The use of vancomycin should be limited to those who are proven or potential carriers of MRSA. When administered, vancomycin should be adequately dosed and combined with a cephalosporin or another antibiotic that has broader pathogen coverage.

References

Alijanipour P, Heller S, Parvizi J. Prevention of periprosthetic joint infection: what are the effective strategies? J Knee Surg. 2014;27:251–258.

Anderson DJ. Prevention of surgical site infection: beyond SCIP. AORN J. 2014;99:315–319.

Annè S, Reisman RE. Risk of administering cephalosporin antibiotics to patients with histories of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1995;74:167–170.

Astagneau P, Rioux C, Golliot F, Brücker G; INCISO Network Study Group. Morbidity and mortality associated with surgical site infections: results from the 1997-1999 INCISO surveillance. J Hosp Infect. 2001;48:267–274.

Bailie GR, Neal D. Vancomycin ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 2012;3:376–386.

Borch JE, Andersen KE, Bindslev-Jensen C. The prevalence of suspected and challenge-verified penicillin allergy in a university hospital population. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;98:357-362.

Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, Perl TM, Auwaerter PG, Bolon MK, Fish DN, Napolitano LM, Sawyer RG, Slain D, Steinberg JP, Weinstein RA; American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Infectious Disease Society of America, Surgical Infection Society, Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70:195–283.

Campagna JD, Bond MC, Schabelman E, Hayes BD. The use of cephalosporins in penicillin-allergic patients: a literature review. J Emerg Med. 2012;42:612–620.

Catanzano A, Phillips M, Dubrovskaya Y, Hutzler L, Bosco J. The standard one gram dose of vancomycin is not adequate prophylaxis for MRSA. Iowa Orthop J. 2014;34:111–117.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383.

Flegal KM. Epidemiologic aspects of overweight and obesity in the United States. Physiol Behav. 2005;86:599–602.

Hansen E, Belden K, Silibovsky R, Vogt M, Arnold WV, Bicanic G, Bini SA, Catani F, Chen J, Ghazavi MT, Godefroy KM, Holham P, Hosseinzadeh H, Kim KII, Kirketerp-Møller K, Lidgren L, Lin JH, Lonner JH, Moore CC, Papagelopoulos P, Poultsides L, Randall RL, Roslund B, Saleh K, Salmon JV, Schwarz EM, Stuyck J, Dahl AW, Yamada K. Perioperative antibiotics. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:29–48.

Holm A, Mosbech H. Challenge test results in patients with suspected penicillin allergy, but no specific IgE. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:118–122.

Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, Kaplan SL, Karchmer AW, Levine DP, Murray BE, J Rybak M, Talan DA, Chambers HF; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e18–55.

Manrique J, Chen AF, Gomez MM, Maltenfort MG, Hozack WJ. Surgical site infection and transfusion rates are higher in underweight total knee arthroplasty patients. Arthroplasty Today. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.artd.2016.03.005. Accessed October 29, 2016.

Mellor JA, Kingdom J, Cafferkey M, Keane CT. Vancomycin toxicity: a prospective study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985;15:773–780.

Moise PA, Sakoulas G, Forrest A, Schentag JJ. Vancomycin in vitro bactericidal activity and its relationship to efficacy in clearance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2582–2586.

Pai MP, Bearden DT. Antimicrobial dosing considerations in obese adult patients. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2007;27:1081–1091.

Pan S, Zhu L, Chen M, Xia P, Zhou Q. Weight-based dosing in medication use: what should we know? Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:549–560.

Parvizi J, Zmistowski B, Berbari EF, Bauer TW, Springer BD, Della Valle CJ, Garvin KL, Mont MA, Wongworawat MD, Zalavras CG. New definition for periprosthetic joint infection: from the Workgroup of the Musculoskeletal Infection Society. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:2992–2994.

Ponce B, Raines BT, Reed RD, Vick C, Richman J, Hawn M. Surgical site infection after arthroplasty: comparative effectiveness of prophylactic antibiotics: do Surgical Care Improvement Project guidelines need to be updated? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:970–977.

Pritchard L, Baker C, Leggett J, Sehdev P, Brown A, Bayley KB. Increasing vancomycin serum trough concentrations and incidence of nephrotoxicity. Am J Med. 2010;123:1143–1149.

Rybak MJ, Albrecht LM, Boike SC, Chandrasekar PH. Nephrotoxicity of vancomycin, alone and with an aminoglycoside. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;25:679–687.

Rybak MJ, Lomaestro BM, Rotschafer JC, Moellering RC, Craig WA, Billeter M, Dalovisio JR, Levine DP. Vancomycin therapeutic guidelines: a summary of consensus recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:325–327.

Sayeed Z, Anoushiravani AA, Chambers MC, Gilbert TJ, Scaife SL, El-Othmani MM, Saleh KJ. Comparing in-hospital total joint arthroplasty outcomes and resource consumption among underweight and morbidly obese patients. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:2085–2090.

Sewick A, Makani A, Wu C, O’Donnell J, Baldwin KD, Lee G-C. Does dual antibiotic prophylaxis better prevent surgical site infections in total joint arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:2702–2707.

Shahi A, Parvizi J. Prevention of periprosthetic joint infection. Arch.Bone Joint Surg. 2015;3:72–81.

Smith EB, Wynne R, Joshi A, Liu H, Good RP. Is it time to include vancomycin for routine perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in total joint arthroplasty patients? J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(Suppl):55-60.

Sorrell TC, Collignon PJ. A prospective study of adverse reactions associated with vancomycin therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985;16:235–241.

Tan TL, Springer BD, Ruder JA, Ruffolo MR, Chen AF. Is vancomycin-only prophylaxis for patients with penicillin allergy associated with increased risk of infection after arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1601–1606.

Tyllianakis ME, Karageorgos AC, Marangos MN, Saridis AG, Lambiris EE. Antibiotic prophylaxis in primary hip and knee arthroplasty: comparison between cefuroxime and two specific antistaphylococcal agents. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:1078–1082.

Van Hal SJ, Paterson DL, Lodise TP. Systematic review and meta-analysis of vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity associated with dosing schedules that maintain troughs between 15 and 20 milligrams per liter. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:734–744.

Acknowledgments

We thank Raymond Nelan BS, for his electronic query of our database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

One author certifies that he (JP) has or may receive payments or benefits, during the study period, an amount of USD 10,000 to USD 100,000 from Zimmer Biomet (Warsaw, IN, USA); an amount of less than USD 10,000 from ConvaTec (Skillman, NJ, USA); an amount of USD 10,000 from TissueGene (Rockville, MD, USA); an amount of less than USD 10,000 from CeramTec (Plochingen, Germany); and an amount of less than USD 10,000 from Ethicon (Somerville, NJ, USA). One author certifies that he (JP) has stock options with Parvizi Surgical Innovations (Philadelphia, PA, USA); Hip Innovation Technology (Plantation, FL, USA); CD Diagnostics (Wynnewood, PA, USA); CorenTec (Seoul, Korea); Alphaeon (Irvine, CA, USA); Joint Purification Systems (Solana Beach, CA, USA); Ceribell (Mountain View, CA, USA); MedAP (Cape Town, South Africa); Cross Current Business Intelligence (Doylestown, PA, USA); Invisible Sentinel (Philadelphia, PA, USA); Physician Recommended Nutriceuticals (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA); Intellijoint (Waterloo, Ontario, Canada); and MicroGenDx (Tallahassee, FL, USA). One author certifies that he (JP) has or may receive royalties during the study period in the amount of less than USD 10,000 from Corentec (Seoul, Korea); an amount of less than USD 10,000 from Datatrace (Houston, TX, USA); an amount of less than USD 10,000 from Elsevier (Philadelphia, PA, USA); an amount of less than USD 10,000 from Wolters-Kluwer (Philadelphia, PA, USA); an amount of less than USD 10,000 from Slack Inc (Thorofare, NJ, USA); and an amount of less than USD 10,000 from Jaypee (New Delhi, India). One author certifies that he (JP) has a board membership with the Journal of Arthroplasty; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery; Bone and Joint Journal; Eastern Orthopaedic Association (Towson, MD, USA); Muller Foundation (Baltimore, MD, USA); and United Healthcare (Hopkins, MN, USA).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

About this article

Cite this article

Kheir, M.M., Tan, T.L., Azboy, I. et al. Vancomycin Prophylaxis for Total Joint Arthroplasty: Incorrectly Dosed and Has a Higher Rate of Periprosthetic Infection Than Cefazolin. Clin Orthop Relat Res 475, 1767–1774 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-017-5302-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-017-5302-0