Opinion statement

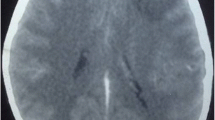

Cysticercosis, the consequence of ingesting viable eggs of the porcine tapeworm Taenia solium, currently remains one of the most common human parasitic conditions worldwide. Although preventable by the proper disposal of human wastes, cysticercosis of the central nervous system (neurocysticercosis) accounts for a substantial proportion of cases of epilepsy and hydrocephalus among children and adults in many developing countries. Cases also occur in nonendemic regions, reflecting patterns of immigration from highly endemic countries, especially Mexico and other areas of Latin America. Antiparasitic treatment during active infections, using albendazole or praziquantel, can eradicate the parasite, may lower the risk of late complications, and potentially reduces the morbidity of acute disease. Considerable controversy persists regarding the role of antiparasitic therapy in neurocysticercosis, however. Persons with active parenchymal or extraparenchymal disease, defined by the neuroradiographic appearance of lesions, can be treated with albendazole, 15 mg/kg/d divided into two daily doses for 8 days. Patients with parenchymal disease who do not respond to albendazole can receive a second course of albendazole or praziquantel, 50 mg/kg/d divided into three daily doses for 15 days. Concurrent administration of dexamethasone in standard doses is usually required during the first several days of antiparasitic therapy to minimize the inflammation and cerebral edema associated with death of the parasites. Patients with intraventricular cysts and hydrocephalus require shunting and surgical removal of cysticerci. By contrast, persons with inactive lesions and seizures as a consequence of remote infections typically require only symptomatic therapy with standard anticonvulsants.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

White AC: Neurocysticercosis: a major cause of neurological disease worldwide. Clin Infect Dis 1997, 24:101–105. A well-written, extremely comprehensive review that summarizes the fascinating immunopathogenesis of neurocysticercosis and the current controversies regarding the role of antihelminthic therapy in the treatment of the disorder. If there is time to read but one article regarding neurocysticercosis, this should be the one.

Sotelo J: Neurocysticercosis. In Central Nervous System Diseases and Therapy. Edited by Roos K. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1997:545–572. A thorough review of the condition by a very knowledgeable expert in the diagnosis and treatment of neurocysticercosis.

Lettau LA, Gardner S, Tennis J, et al.: Locally acquired neurocysticercosis—North Carolina, Massachusetts, and South Carolina, 1989–1991. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1992, 41:1–4.

Mitchell WG, Crawford TO: Intraparenchymal cerebral cysticercosis in children: diagnosis and treatment. Pediatrics 1988, 82:76–82.

Scharf D: Neurocysticercosis: two hundred and thirty eight cases from a California hospital. Arch Neurol 1988, 45:777–780.

Sotelo J, Guerrero V, Rubio F: Neurocysticercosis: a new classification based on active and inactive forms. Arch Intern Med 1985, 145:442–445.

Del Brutto OH, Santibanez R, Noboa CA, et al.: Epilepsy due to neurocysticercosis: analysis of 203 patients. Neurology 1992, 42:389–392.

Carpio A, Escobar A, Hauser WA: Cysticercosis and epilepsy: a critical review. Epilepsia 1998, 39:1025–1040. A well-written review that emphasizes the importance of neurocysticercosis as a major cause of epilepsy in regions endemic for T. solium. The article contains an excellent summary of the epidemiology of neurocysticercosis and epilepsy and discusses the concept of transitional forms of neurocysticercosis.

Sotelo J, Marin C: Hydrocephalus secondary to cysticercotic arachnoiditis. J Neurosurg 1987, 66:686–689.

Lotz J, Hewlett R, Alheit B, Bowen R: Neurocysticercosis: correlative pathology and MR imaging. Neuroradiology 1988, 30:35–41.

Wilson M, Bryan RT, Fried JA, et al.: Clinical evaluation of the cysticercosis enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot in patients with neurocysticercosis. J Infect Dis 1991, 164:1007–1009.

St.Geme JW, Maldonado YA, Enzmann D, et al.: Consensus: diagnosis and management of neurocysticercosis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1993, 12:455–461. A summary of expert opinions regarding the treatment of neurocysticercosis presented in a point-counterpoint fashion.

Kramer LD: Medical treatment of cysticercosis: ineffective. Arch Neurol 1995, 52:101–102. Together with Del Brutto’s article on pages 102 to 104 of the same issue, which champions the effectiveness of medical treatment, this is another concise point-counterpoint debate regarding the benefits of specific antiparasitic therapy in neurocysticercosis.

Del Brutto OH, Sotelo J, Roman GC: Therapy for neurocysticercosis: a reappraisal. Clin Infect Dis 1993, 17:30–35. Although somewhat older, this article summarizes well the approach to managing neurocysticercosis based on the location of infection.

Evans C, Garcia HH, Gilman RH, Friedland JS: Controversies in the management of cysticercosis. Emerg Infect Dis 1997, 3:403–405.

Schantz PM, Moore AC, Munoz JL, et al.: Neurocysticercosis in an orthodox Jewish community in New York City. N Engl J Med 1992, 327:692–695.

Couldwell WT, Zee CS, Apuzzo MLJ: Definition of the role of contemporary surgical management in cisternal and parenchymal cysticercosis cerebri. Neurosurgery 1991, 28:231–237.

Venkatesan P: Albendazole. J Antimicrob Chemother 1998, 41:145–147. A review of the value of albendazole in the treatment of various parasitic diseases.

Garcia HH, Gilman RH, Horton J, et al.: Albendazole therapy for neurocysticercosis: a prospective doubleblind trial comparing 7 versus 14 days of treatment. Neurology 1997, 48:1421–1427. A recent study of the use of albendazole in patients with active neurocysticercosis, using CT appearance of lesions as a major therapeutic outcome measure. Remarkably, only 38% had “complete cure,” defined as radiographic disappearance of all active lesions at 3 months. Three of 10 patients who had “cure” at 3 months had active lesions detected at the 1-year follow-up.

Baranwal AK, Singhi PD, Khandelwal N, et al.: Albendazole therapy in children with focal seizures and single, small enhancing computerized tomographic lesions: a randomized, placebo-controlled, doubleblind trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1998, 17:696–700. This prospective study represents one of the few that have included a placebo control arm. All children received dexamethasone during the first 5 days of therapy. Outcome measures included the CT appearance of lesions and the rates of seizure recurrence. Children who received albendazole had higher rates of lesion resolution (64.5% vs 37.5%; P<0.05) at 3 months and lower rates of recurrent seizures (31.3% vs 12.9%) after 4 weeks, suggesting that albendazole therapy is warranted. Remarkably, nearly 40% of the untreated patients had resolution of lesions at 3 months. One wonders what outcome would be at 1 year of follow-up.

Mehta SS, Hatfield S, Jessen L, Vogel D: Albendazole versus praziquantel for neurocysticercosis. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1998, 55:598–600. An excellent, concise summary of the two currently available drugs used in the treatment of neurocysticercosis. Although efficacy seems nearly equivalent (or slightly in favor of albendazole), the lower cost and cerebrospinal fluid penetration indicate that albendazole should be the drug of choice.

Sotelo J, Escobedo F, Rodriguez-Carbajal J, et al.: Therapy of parenchymal brain cysticercosis with praziquantel. N Engl J Med 1984, 316:1001–1007. One of the first studies to suggest benefit from specific antiparasitic therapy. The study included small numbers, however, did not randomize, and used CT appearance of the lesions as the primary outcome measure.

Vazquez V, Sotelo J: The course of seizures after treatment for cerebral cysticercosis. N Engl J Med 1992, 327:696–701. A subsequent study from the same institution concluded that praziquantel therapy reduced the frequency of seizures 3 years after treatment. The retrospective study design detracts from the power of the observation, however.

Del Brutto OH, Campos X, Sanchez J, Mosquera A: Single day praziquantel versus 1 week albendazole for neurocysticercosis. Neurology 1999, 52:1079–1081. A small-scale study, using CT appearance as the outcome measure, that shows no differences between praziquantel and albendazole in these regimens.

Sotelo J, Escobedo R, Penagos P: Albendazole vs. praziquantel for therapy for neurocysticercosis. Arch Neurol 1988, 45:532–533. Another small study that shows no differences between praziquantel and albendazole.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bale, J.F. Cysticercosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2, 355–360 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-000-0052-8

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-000-0052-8