Opinion Statement

The sessile serrated polyp (SSP), also known as sessile serrated adenoma, is the evil twin among the colorectal cancer precursors. As will be described, these lesions have multiple aliases (serrated adenoma, serrated polyp, or serrated lesion among others), they hang out in a bad neighborhood (the poorly prepped right colon), they hide behind a mask of mucus, they are difficult for witnesses (pathologists) to identify, they are difficult for police (endoscopists) to find, they are difficult to permanently remove from the society (high incomplete resection rate), they can be impulsive (progress rapidly to colorectal cancer (CRC)), and enforcers (gastroenterologists) do not know how best to control them (uncertain surveillance recommendations). There is no wonder that there is a need to understand these lesions well, learn how best to prevent the colonic mucosa from going down this errant path or, if that fails, detect these deviants and eradicate them from the colonic society. These lesions should be on endoscopists’ most wanted list.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

Longacre TA, Fenoglio-Preiser CM. Mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps/serrated adenomas. A distinct form of colorectal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14(6):524–37.

Torlakovic E et al. Morphologic reappraisal of serrated colorectal polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(1):65–81.

Rex DK et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1315–29. quiz 1314, 1330.

Montgomery E. Serrated colorectal polyps: emerging evidence suggests the need for a reappraisal. Adv Anat Pathol. 2004;11(3):143–9.

Bosman FT, World Health Organization., and International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2010. 417 p.

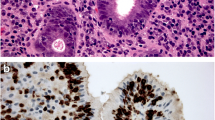

Bettington M et al. Critical appraisal of the diagnosis of the sessile serrated adenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(2):158–66.

Kim SW et al. A significant number of sessile serrated adenomas might not be accurately diagnosed in daily practice. Gut Liver. 2010;4(4):498–502.

Tinmouth J, et al. Sessile serrated polyps at screening colonoscopy: have they been under diagnosed? Am J Gastroenterol. 2014.

Singh H et al. Pathological reassessment of hyperplastic colon polyps in a city-wide pathology practice: implications for polyp surveillance recommendations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(5):1003–8.

Lieberman DA et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(3):844–57.

Vogelstein B et al. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(9):525–32.

Bettington M et al. The serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma: current concepts and challenges. Histopathology. 2013;62(3):367–86.

Yang S et al. BRAF and KRAS mutations in hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas of the colorectum: relationship to histology and CpG island methylation status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(11):1452–9.

Crockett SD, et al. Sessile serrated adenomas: an evidence-based guide to management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013.

Singh H et al. The reduction in colorectal cancer mortality after colonoscopy varies by site of the cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(4):1128–37.

Brenner H et al. Protection from colorectal cancer after colonoscopy: a population-based, case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(1):22–30.

Farrar WD et al. Colorectal cancers found after a complete colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(10):1259–64.

Arain MA et al. CIMP status of interval colon cancers: another piece to the puzzle. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(5):1189–95.

Pohl H et al. Incomplete polyp resection during colonoscopy-results of the complete adenoma resection (CARE) study. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(1):74–80.e1.

Leung K et al. Ongoing colorectal cancer risk despite surveillance colonoscopy: the Polyp Prevention Trial Continued Follow-up Study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(1):111–7.

Robertson DJ et al. Colorectal cancers soon after colonoscopy: a pooled multicohort analysis. Gut. 2014;63(6):949–56.

Sanaka MR et al. Adenoma and sessile serrated polyp detection rates: variation by patient sex and colonic segment but not specialty of the endoscopist. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(9):1113–9.

Hetzel JT et al. Variation in the detection of serrated polyps in an average risk colorectal cancer screening cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(12):2656–64.

Kim HY et al. Age-specific prevalence of serrated lesions and their subtypes by screening colonoscopy: a retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:82.

Hazewinkel Y et al. Prevalence of serrated polyps and association with synchronous advanced neoplasia in screening colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2014;46(3):219–24.

Lash RH, Genta RM, Schuler CM. Sessile serrated adenomas: prevalence of dysplasia and carcinoma in 2139 patients. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63(8):681–6.

Kahi CJ et al. Prevalence and variable detection of proximal colon serrated polyps during screening colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(1):42–6.

de Wijkerslooth TR et al. Differences in proximal serrated polyp detection among endoscopists are associated with variability in withdrawal time. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77(4):617–23.

Payne SR et al. Endoscopic detection of proximal serrated lesions and pathologic identification of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps vary on the basis of center. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(7):1119–26.

Abdeljawad K, et al. Sessile serrated polyp prevalence determined by a colonoscopist with a high lesion detection rate and an experienced pathologist. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014.

Butterly L et al. Serrated and adenomatous polyp detection increases with longer withdrawal time: results from the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(3):417–26.

Anderson JC et al. Impact of fair bowel preparation quality on adenoma and serrated polyp detection: data from the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry by using a standardized preparation-quality rating. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80(3):463–70.

Tadepalli US et al. A morphologic analysis of sessile serrated polyps observed during routine colonoscopy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(6):1360–8.

Sato R et al. The diagnostic accuracy of high-resolution endoscopy, autofluorescence imaging and narrow-band imaging for differentially diagnosing colon adenoma. Endoscopy. 2011;43(10):862–8.

Pasha SF et al. Comparison of the yield and miss rate of narrow band imaging and white light endoscopy in patients undergoing screening or surveillance colonoscopy: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(3):363–70. quiz 371.

Omata F et al. Image-enhanced, chromo, and cap-assisted colonoscopy for improving adenoma/neoplasia detection rate: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49(2):222–37.

Kashida H et al. Endoscopic characteristics of colorectal serrated lesions. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58(109):1163–7.

Hazewinkel Y et al. Endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas: validation by international experts using high-resolution white-light endoscopy and narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77(6):916–24.

Boparai KS et al. Increased polyp detection using narrow band imaging compared with high resolution endoscopy in patients with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome. Endoscopy. 2011;43(8):676–82.

Kamiński MF et al. Advanced imaging for detection and differentiation of colorectal neoplasia: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2014;46(5):435–49.

Harrison M, Singh N, Rex DK. Impact of proximal colon retroflexion on adenoma miss rates. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(3):519–22.

Hewett DG, Rex DK. Miss rate of right-sided colon examination during colonoscopy defined by retroflexion: an observational study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(2):246–52.

Pishvaian AC, Al-Kawas FH. Retroflexion in the colon: a useful and safe technique in the evaluation and resection of sessile polyps during colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(7):1479–83.

Yen AW, Leung JW, Leung FW. A new method for screening and surveillance colonoscopy: combined water-exchange and cap-assisted colonoscopy. J Interv Gastroenterol. 2012;2(3):114–9.

Singh R et al. Real-time histology with the endocytoscope. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(40):5016–9.

Kudo S et al. Diagnosis of colorectal tumorous lesions by magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44(1):8–14.

Kimura T et al. A novel pit pattern identifies the precursor of colorectal cancer derived from sessile serrated adenoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(3):460–9.

Kutsukawa M et al. Efficiency of endocytoscopy in differentiating types of serrated polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79(4):648–56.

Patel SG, Ahnen DJ. Prevention of interval colorectal cancers: what every clinician needs to know. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(1):7–15.

Pohl H, Robertson DJ. Colorectal cancers detected after colonoscopy frequently result from missed lesions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(10):858–64.

Gurudu SR et al. Sessile serrated adenomas: demographic, endoscopic and pathological characteristics. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(27):3402–5.

Fahrtash-Bahin F et al. Snare tip soft coagulation achieves effective and safe endoscopic hemostasis during wide-field endoscopic resection of large colonic lesions (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78(1):158–163.e1.

Jung M. The ‘difficult’ polyp: pitfalls for endoscopic removal. Dig Dis. 2012;30 Suppl 2:74–80.

Binmoeller KF et al. “Underwater” EMR without submucosal injection for large sessile colorectal polyps (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75(5):1086–91.

Wang AY et al. Underwater endoscopic mucosal resection of colorectal neoplasia is easily learned, efficacious, and safe. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(4):1348–54.

Omata F et al. Modifiable risk factors for colorectal neoplasms and hyperplastic polyps. Intern Med. 2009;48(3):123–8.

Terry MB et al. Risk factors for advanced colorectal adenomas: a pooled analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(7):622–9.

Aune D et al. Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2011;343:d6617.

Clark JC et al. Prevalence of polyps in an autopsy series from areas with varying incidence of large-bowel cancer. Int J Cancer. 1985;36(2):179–86.

Kearney J et al. Diet, alcohol, and smoking and the occurrence of hyperplastic polyps of the colon and rectum (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 1995;6(1):45–56.

Martínez ME et al. A case-control study of dietary intake and other lifestyle risk factors for hyperplastic polyps. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(2):423–9.

Shrubsole MJ et al. Alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and risk of colorectal adenomatous and hyperplastic polyps. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(9):1050–8.

Schreiner MA, Weiss DG, Lieberman DA. Proximal and large hyperplastic and nondysplastic serrated polyps detected by colonoscopy are associated with neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(5):1497–502.

Wallace K et al. The association of lifestyle and dietary factors with the risk for serrated polyps of the colorectum. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(8):2310–7.

Burnett-Hartman AN et al. Differences in epidemiologic risk factors for colorectal adenomas and serrated polyps by lesion severity and anatomical site. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(7):625–37.

Chia VM et al. Risk of microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer is associated jointly with smoking and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. Cancer Res. 2006;66(13):6877–83.

Algra AM, Rothwell PM. Effects of regular aspirin on long-term cancer incidence and metastasis: a systematic comparison of evidence from observational studies versus randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(5):518–27.

Burn J et al. Long-term effect of aspirin on cancer risk in carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer: an analysis from the CAPP2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9809):2081–7.

Kawasaki T et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression is common in serrated and non-serrated colorectal adenoma, but uncommon in hyperplastic polyp and sessile serrated polyp/adenoma. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:33.

Nishihara R et al. Aspirin use and risk of colorectal cancer according to BRAF mutation status. JAMA. 2013;309(24):2563–71.

Liao X et al. Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(17):1596–606.

Rosty C et al. Phenotype and polyp landscape in serrated polyposis syndrome: a series of 100 patients from genetics clinics. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(6):876–82.

Cathomas G. PIK3CA in colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2014;4:35.

Bouwens MW et al. Simple clinical risk score identifies patients with serrated polyps in routine practice. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2013;6(8):855–63.

Vu HT et al. Individuals with sessile serrated polyps express an aggressive colorectal phenotype. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(10):1216–23.

Snover D, Ahnen DJ, Burt RW, Odze RD. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum and serrated polyposis. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC; 2010. p. 160–5.

Biswas S et al. High prevalence of hyperplastic polyposis syndrome (serrated polyposis) in the NHS bowel cancer screening programme. Gut. 2013;62(3):475.

Boparai KS et al. Increased colorectal cancer risk during follow-up in patients with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome: a multicentre cohort study. Gut. 2010;59(8):1094–100.

Kalady MF et al. Defining phenotypes and cancer risk in hyperplastic polyposis syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(2):164–70.

Hyman NH, Anderson P, Blasyk H. Hyperplastic polyposis and the risk of colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(12):2101–4.

Boparai KS et al. Increased colorectal cancer risk in first-degree relatives of patients with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome. Gut. 2010;59(9):1222–5.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Joshua C. Obuch and Courtney M. Pigott declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Dennis J. Ahnen has received board membership payments and paid travel accommodations from EXACT Sciences, Inc., and board membership payments from Cancer Prevention Pharmaceuticals.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Colon

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Obuch, J.C., Pigott, C.M. & Ahnen, D.J. Sessile Serrated Polyps: Detection, Eradication, and Prevention of the Evil Twin. Curr Treat Options Gastro 13, 156–170 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-015-0046-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-015-0046-y