Abstract

Malaria, which is caused by Plasmodium parasite erythrocyte infection, is a highly inflammatory disease with characteristic periodic fevers caused by the synchronous rupture of infected erythrocytes to release daughter parasites. Despite the importance of inflammation in the pathology and mortality induced by malaria, the parasite-derived factors inducing the inflammatory response are still not well characterized. Uric acid is emerging as a central inflammatory molecule in malaria. Not only is uric acid found in the precipitated form in infected erythrocytes, but high concentrations of hypoxanthine, a precursor for uric acid, also accumulate in infected erythrocytes. Both are released upon infected erythrocyte rupture into the circulation where hypoxanthine would be converted into uric acid and precipitated uric acid would encounter immune cells. Uric acid is an important contributor to inflammatory cytokine secretion, dendritic cell and T cell responses induced by Plasmodium, suggesting uric acid as a novel molecular target for anti-inflammatory therapies in malaria.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •Of importance ••Of major importance

Golgi C. Sull Infezione malarica. Arch Sci Med (Torino). 1886;10:109–1.

Kwiatkowski D. Malarial toxins and the regulation of parasite density. Parasitol Today. 1995;11:206–12.

Clark IA, Cowden WB. The pathophysiology of falciparum malaria. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;99:221–60.

Haldar K and Mohandas N. Malaria, erythrocytic infection, and anemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009;87-93.

van der Heyde HC, Nolan J, Combes V, et al. A unified hypothesis for the genesis of cerebral malaria: sequestration, inflammation and hemostasis leading to microcirculatory dysfunction. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:503–8.

Schofield L, Hackett F. Signal transduction in host cells by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol toxin of malaria parasites. J Exp Med. 1993;177:145–53.

Coban C, Ishii KJ, Kawai T, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 mediates innate immune activation by the malaria pigment hemozoin. J Exp Med. 2005;201:19–25.

Griffith JW, Sun T, McIntosh MT, Bucala R. Pure Hemozoin is inflammatory in vivo and activates the NALP3 inflammasome via release of uric acid. J Immunol. 2009;183:5208–20.

Parroche P, Lauw FN, Goutagny N, et al. Malaria hemozoin is immunologically inert but radically enhances innate responses by presenting malaria DNA to Toll-like receptor 9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1919–24.

Sharma S, DeOliveira RB, Kalantari P, et al. Innate immune recognition of an AT-rich stem-loop DNA motif in the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Immunity. 2011;35:194–207.

Wu X, Gowda NM, Kumar S, Gowda DC. Protein-DNA complex is the exclusive malaria parasite component that activates dendritic cells and triggers innate immune responses. J Immunol. 2010;184:4338–48.

Gowda NM, Wu X, Gowda DC. The nucleosome (histone-DNA complex) is the TLR9-specific immunostimulatory component of Plasmodium falciparum that activates DCs. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20398.

Erdman LK, Finney CA, Liles WC, Kain KC. Inflammatory pathways in malaria infection: TLRs share the stage with other components of innate immunity. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;162:105–11.

Busso N, So A. Mechanisms of inflammation in gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:206.

Shi Y, Evans JE, Rock KL. Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature. 2003;425:516–21.

Gero AM, O’Sullivan WJ. Purines and pyrimidines in malarial parasites. Blood Cells. 1990;16:467–84. discussion 485-98.

Asahi H, Kanazawa T, Kajihara Y, et al. Hypoxanthine: a low molecular weight factor essential for growth of erythrocytic Plasmodium falciparum in a serum-free medium. Parasitology. 1996;113(Pt 1):19–23.

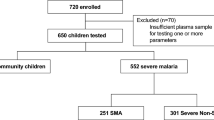

Orengo JM, Evans JE, Bettiol E, et al. Plasmodium-induced inflammation by uric acid. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000013. This work shows for the first time that Plasmodium-derived uric acid induces an inflammatory response.

Orengo JM, Leliwa-Sytek A, Evans JE, et al. Uric acid is a mediator of the Plasmodium falciparum-induced inflammatory response. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5194. This work shows inflammation by uric acid derived from the human parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

Reyes P, Rathod PK, Sanchez DJ, et al. Enzymes of purine and pyrimidine metabolism from the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1982;5:275–90.

Heath WR, Carbone FR. Immunology: dangerous liaisons. Nature. 2003;425:460–1.

Guermonprez P, Helft J, Claser C, et al. Inflammatory Flt3l is essential to mobilize dendritic cells and for T cell responses during Plasmodium infection. Nat Med. 2013;19:730–8. This work shows the role of uric acid in regulating the adaptive immune response to Plasmodium.

van de Hoef DL, Coppens I, Holowka T, et al. Plasmodium falciparum-derived uric acid precipitates induce maturation of dendritic cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55584. This work shows the presence of inflammatory uric acid precipitates in human Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes.

Overgaard-Hansen K, Lassen UV. Active transport of uric acid through the human erythrocyte membrane. Nature. 1959;184:553–4.

Grau GE, Piguet PF, Vassalli P, Lambert PH. Tumor-necrosis factor and other cytokines in cerebral malaria: experimental and clinical data. Immunol Rev. 1989;112:49–70.

Kwiatkowski D, Hill AV, Sambou I, et al. TNF concentration in fatal cerebral, non-fatal cerebral, and uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Lancet. 1990;336:1201–4.

Kutzing MK, Firestein BL. Altered uric acid levels and disease states. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:1–7.

Glantzounis GK, Tsimoyiannis EC, Kappas AM, Galaris DA. Uric acid and oxidative stress. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:4145–51.

Alvarez-Lario B, Macarron-Vicente J. Uric acid and evolution. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49:2010–5.

Johnson RJ, Andrews P, Benner SA, Oliver W. Theodore E. Woodward award. The evolution of obesity: insights from the mid-Miocene. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2010;121:295–305. discussion 305-8.

Johnson RJ, Titte S, Cade JR, et al. Uric acid, evolution and primitive cultures. Semin Nephrol. 2005;25:3–8.

Smyth CJ and Holers VM, Gout, hyperuricemia, and other crystal-associated arthropathies. 1999, New York: M. Dekker. xvii, 401 p.

Bertrand KE, Mathieu N, Inocent G, Honore FK. Antioxidant status of bilirubin and uric acid in patients diagnosed with Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Douala. Pak J Biol Sci. 2008;11:1646–9.

Das BS, Patnaik JK, Mohanty S, et al. Plasma antioxidants and lipid peroxidation products in falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:720–5.

Iwalokun BA, Bamiro SB, Ogunledun A. Levels and interactions of plasma xanthine oxidase, catalase and liver function parameters in Nigerian children with Plasmodium falciparum infection. Apmis. 2006;114:842–50.

Lopera-Mesa TM, Mita-Mendoza NK, van de Hoef DL, et al. Plasma uric acid levels correlate with inflammation and disease severity in Malian children with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46424. This work shows there is a correlation between inflammatory cytokines and levels of uric acid in malaria patients.

Mita-Mendoza NK, van de Hoef DL, Lopera-Mesa TM, et al. A potential role for plasma uric acid in the endothelial pathology of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54481. This work shows a correlation between the levels of markers of endothelial cell stress and uric acid in malaria patients.

Mishra SK, Das BS. Malaria and acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol. 2008;28:395–408.

Zhou Y, Fang L, Jiang L, et al. Uric acid induces renal inflammation via activating tubular NF-kappaB signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39738.

Sarma PS, Mandal AK, Khamis HJ. Allopurinol as an additive to quinine in the treatment of acute complicated falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:454–7.

Marr JJ. Purine analogs as chemotherapeutic agents in leishmaniasis and American trypanosomiasis. J Lab Clin Med. 1991;118:111–9.

Gillman BM, Batchelder J, Flaherty P, Weidanz WP. Suppression of Plasmodium chabaudi parasitemia is independent of the action of reactive oxygen intermediates and/or nitric oxide. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6359–66.

Kanellis J, Kang DH. Uric acid as a mediator of endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and vascular disease. Semin Nephrol. 2005;25:39–42.

Jin M, Yang F, Yang I, et al. Uric acid, hyperuricemia and vascular diseases. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2012;17:656–69.

Watt G, Jongsakul K, Ruangvirayuth R. A pilot study of N-acetylcysteine as adjunctive therapy for severe malaria. QJM. 2002;95:285–90.

Rasti N, Wahlgren M, Chen Q. Molecular aspects of malaria pathogenesis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;41:9–26.

Hunt NH, Grau GE. Cytokines: accelerators and brakes in the pathogenesis of cerebral malaria. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:491–9.

Johnson RJ, Kang DH, Feig D, et al. Is there a pathogenetic role for uric acid in hypertension and cardiovascular and renal disease? Hypertension. 2003;41:1183–90.

Sautin YY, Johnson RJ. Uric acid: the oxidant-antioxidant paradox. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2008;27:608–19.

Schwartz IF, Grupper A, Chernichovski T, et al. Hyperuricemia attenuates aortic nitric oxide generation, through inhibition of arginine transport, in rats. J Vasc Res. 2011;48:252–60.

Zharikov S, Krotova K, Hu H, et al. Uric acid decreases NO production and increases arginase activity in cultured pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C1183–90.

Tomiyama H, Higashi Y, Takase B, et al. Relationships among hyperuricemia, metabolic syndrome, and endothelial function. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:770–4.

Hanson SR, Harker LA. Interruption of acute platelet-dependent thrombosis by the synthetic antithrombin D-phenylalanyl-L-prolyl-L-arginyl chloromethyl ketone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:3184–8.

Combes V, Coltel N, Faille D, et al. Cerebral malaria: role of microparticles and platelets in alterations of the blood-brain barrier. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:541–6.

Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, et al. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440:237–41.

Reimer T, Shaw MH, Franchi L, et al. Experimental cerebral malaria progresses independently of the Nlrp3 inflammasome. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:764–9.

Kordes M, Matuschewski K, Hafalla JC. Caspase-1 activation of interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta) and IL-18 is dispensable for induction of experimental cerebral malaria. Infect Immun. 2011;79:3633–41.

Kanbay M, Segal M, Afsar B, et al. The role of uric acid in the pathogenesis of human cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2013;99:759–66.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Julio Gallego-Delgado, Maureen Ty, Jamie M. Orengo, Diana van de Hoef, and Ana Rodriguez declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human subjects performed by any of the authors. With regard to the authors’ research cited in this paper, all institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Crystal Arthritis

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gallego-Delgado, J., Ty, M., Orengo, J.M. et al. A Surprising Role for Uric Acid: The Inflammatory Malaria Response. Curr Rheumatol Rep 16, 401 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-013-0401-8

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-013-0401-8