Abstract

Purpose of Review

Imaging research has sought to uncover brain structure, function, and metabolism in women with postpartum depression (PPD) as little is known about its underlying pathophysiology. This review discusses the imaging modalities used to date to evaluate postpartum depression and highlights recent findings.

Recent Findings

Altered functional connectivity and activity changes in brain areas implicated in executive functioning and emotion and reward processing have been identified in PPD. Metabolism changes involving monoamine oxidase A, gamma-aminobutyric acid, glutamate, serotonin, and dopamine have additionally been reported. To date, no studies have evaluated gray matter morphometry, voxel-based morphometry, surface area, cortical thickness, or white matter tract integrity in PPD.

Summary

Recent imaging studies report changes in functional connectivity and metabolism in women with PPD vs. healthy comparison women. Future research is needed to extend these findings as they have important implications for the prevention and treatment of postpartum mood disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Kendell RE, Chalmers JC, Platz C. Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:662–73.

Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Mors O, Mortensen PB. New parents and mental disorders: a population-based register study. JAMA. 2006;296(21):2582–9.

Valdimarsdottir U, Hultman CM, Harlow B, Cnattingius S, Sparen P. Psychotic illness in first-time mothers with no previous psychiatric hospitalizations: a population-based study. PLoS Med. 2009;6(2):e13.

O'Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Wright EJ. Prospective study of postpartum blues. Biologic and psychosocial factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(9):801–6.

Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(2):139G–49G.

Tebeka S, Le Strat Y, Dubertret C. Developmental trajectories of pregnant and postpartum depression in an epidemiologic survey. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:62–8.

O'Hara MW, Swain A. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8(1):37–54.

Wisner KL, Chambers C, Sit DK. Postpartum depression: a major public health problem. JAMA. 2006;296(21):2616–8.

Fisher J, Tran T, La BT, Kriitmaa K, Rosenthal D, Tran T. Common perinatal mental disorders in northern Viet Nam: community prevalence and health care use. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(10):737–45.

Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, Maj M, Maselko J, Phillips MR, et al. No health without mental health. Lancet (London, England). 2007;370(9590):859–77.

Hu R, Li Y, Zhang Z, Yan W. Antenatal depressive symptoms and the risk of preeclampsia or operative deliveries: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119018.

Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):77–87.

Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):1012–24.

Turner C, Boyle F, O'Rourke P. Mothers’ health post-partum and their patterns of seeking vaccination for their infants. Int J Nurs Pract. 2003;9(2):120–6.

Minkovitz CS, Strobino D, Scharfstein D, Hou W, Miller T, Mistry KB, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms and children’s receipt of health care in the first 3 years of life. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):306–14.

Rahman A, Iqbal Z, Bunn J, Lovel H, Harrington R. Impact of maternal depression on infant nutritional status and illness: a cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):946–52.

Rahman A, Bunn J, Lovel H, Creed F. Maternal depression increases infant risk of diarrhoeal illness: a cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(1):24–8.

Wisner KL, Parry BL, Piontek CM. Clinical practice. Postpartum depression. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(3):194–9.

Grace SL, Evindar A, Stewart DE. The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: a review and critical analysis of the literature. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2003;6(4):263–74.

Murray L. The impact of postnatal depression on infant development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1992;33(3):543–61.

Halligan SL, Murray L, Martins C, Cooper PJ. Maternal depression and psychiatric outcomes in adolescent offspring: a 13-year longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2007;97(1–3):145–54.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Robertson E, Celasun N, Stewart DE. Risk factors for postpartum depression. In: Stewart DE, Robertson E, Dennis C-L, Grace SL, Wallington T, editors. Postpartum depression: literature review of risk factors and interventions. Toronto: World Health Organization; 2003.

Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment (PACT) Consortium. Heterogeneity of postpartum depression: a latent class analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(1):59–67.

Bloch M, Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ, Lotsikas A, Chrousos GP, Cizza G. Cortisol response to ovine corticotropin-releasing hormone in a model of pregnancy and parturition in euthymic women with and without a history of postpartum depression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(2):695–9.

Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, Murphy J, Nieman L, Rubinow DR. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):924–30.

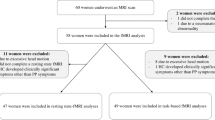

• Deligiannidis KM, Sikoglu EM, Shaffer SA, Frederick B, Svenson AE, Kopoyan A, et al. GABAergic neuroactive steroids and resting-state functional connectivity in postpartum depression: a preliminary study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(6):816–28. This study evaluated resting-state connectivity in women with PPD and healthy postpartum women and demonstrated decreased functional connectivity in brain areas previously implicated in non-puerperal depression.

Harris B, Lovett L, Newcombe RG, Read GF, Walker R, Riad-Fahmy D. Maternity blues and major endocrine changes: Cardiff puerperal mood and hormone study II. BMJ. 1994;308(6934):949–53.

Magiakou MA, Mastorakos G, Rabin D, Dubbert B, Gold PW, Chrousos GP. Hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone suppression during the postpartum period: implications for the increase in psychiatric manifestations at this time. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(5):1912–7.

Stuebe AM, Grewen K, Pedersen CA, Propper C, Meltzer-Brody S. Failed lactation and perinatal depression: common problems with shared neuroendocrine mechanisms? J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2012;21(3):264–72.

Hellgren C, Akerud H, Skalkidou A, Sundstrom-Poromaa I. Cortisol awakening response in late pregnancy in women with previous or ongoing depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(12):3150–4.

Meinlschmidt G, Martin C, Neumann ID, Heinrichs M. Maternal cortisol in late pregnancy and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal reactivity to psychosocial stress postpartum in women. Stress. 2010;13(2):163–71.

Nierop A, Bratsikas A, Zimmermann R, Ehlert U. Are stress-induced cortisol changes during pregnancy associated with postpartum depressive symptoms? Psychosom Med. 2006;68(6):931–7.

Corwin EJ, Pajer K, Paul S, Lowe N, Weber M, McCarthy DO. Bidirectional psychoneuroimmune interactions in the early postpartum period influence risk of postpartum depression. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;49:86–93.

Boufidou F, Lambrinoudaki I, Argeitis J, Zervas IM, Pliatsika P, Leonardou AA, et al. CSF and plasma cytokines at delivery and postpartum mood disturbances. J Affect Disord. 2009;115(1–2):287–92.

Sharkey KM, Pearlstein TB, Carskadon MA. Circadian phase shifts and mood across the perinatal period in women with a history of major depressive disorder: a preliminary communication. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):1103–8.

Parry BL, Meliska CJ, Sorenson DL, Lopez AM, Martinez LF, Nowakowski S, et al. Plasma melatonin circadian rhythm disturbances during pregnancy and postpartum in depressed women and women with personal or family histories of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1551–8.

Bandettini PA. What’s new in neuroimaging methods? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1156:260–93.

Kim P, Leckman JF, Mayes LC, Feldman R, Wang X, Swain JE. The plasticity of human maternal brain: longitudinal changes in brain anatomy during the early postpartum period. Behav Neurosci. 2010;124(5):695–700.

Swain JE, Lorberbaum JP, Kose S, Strathearn L. Brain basis of early parent-infant interactions: psychology, physiology, and in vivo functional neuroimaging studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(3–4):262–87.

•• Hoekzema E, Barba-Muller E, Pozzobon C, Picado M, Lucco F, Garcia-Garcia D, et al. Pregnancy leads to long-lasting changes in human brain structure. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20(2):287–96. This prospective fMRI study identified gray matter volume reductions that occurred exclusively as a product of pregnancy and additionally demonstrated that majority of these reductions persist at 2 years postpartum.

Logothetis NK, Pauls J, Augath M, Trinath T, Oeltermann A. Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature. 2001;412(6843):150–7.

van den Heuvel MP, Hulshoff Pol HE. Exploring the brain network: a review on resting-state fMRI functional connectivity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;20(8):519–34.

Glover GH. Overview of functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2011;22(2):133–9. vii

Kaiser RH, Andrews-Hanna JR, Wager TD, Pizzagalli DA. Large-scale network dysfunction in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. JAMA Psychiat. 2015;72(6):603–11.

Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1–38.

Mulders PC, van Eijndhoven PF, Schene AH, Beckmann CF, Tendolkar I. Resting-state functional connectivity in major depressive disorder: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;56:330–44.

Menon V. Salience network. In: Toga AW, editor. Brain mapping: an encyclopedic reference. vol 2. Elsevier: Academic Press; 2015. p. 597–611.

Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci. 2007;27(9):2349–56.

Zanto TP, Gazzaley A. Fronto-parietal network: flexible hub of cognitive control. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(12):602–3.

Vossel S, Geng JJ, Fink GR. Dorsal and ventral attention systems: distinct neural circuits but collaborative roles. Neuroscientist. 2014;20(2):150–9.

Bannbers E, Gingnell M, Engman J, Morell A, Sylven S, Skalkidou A, et al. Prefrontal activity during response inhibition decreases over time in the postpartum period. Behav Brain Res. 2013;241:132–8.

• Gingnell M, Bannbers E, Moes H, Engman J, Sylven S, Skalkidou A, et al. Emotion reactivity is increased 4–6 weeks postpartum in healthy women: a longitudinal fMRI study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128964. This study was the first to address longitudinal changes in emotion-induced brain reactivity in healthy women during the postpartum period using fMRI and found that women had lower reactivity in the right insula, left middle frontal gyrus, and bilateral inferior frontal gyrus in early postpartum when compared to late postpartum.

Silverman ME, Loudon H, Safier M, Protopopescu X, Leiter G, Liu X, et al. Neural dysfunction in postpartum depression: an fMRI pilot study. CNS Spectr. 2007;12(11):853–62.

Silverman ME, Loudon H, Liu X, Mauro C, Leiter G, Goldstein MA. The neural processing of negative emotion postpartum: a preliminary study of amygdala function in postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(4):355–9.

Moses-Kolko EL, Perlman SB, Wisner KL, James J, Saul AT, Phillips ML. Abnormally reduced dorsomedial prefrontal cortical activity and effective connectivity with amygdala in response to negative emotional faces in postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1373–80.

Moses-Kolko EL, Fraser D, Wisner KL, James JA, Saul AT, Fiez JA, et al. Rapid habituation of ventral striatal response to reward receipt in postpartum depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(4):395–9.

•• Wonch KE, de Medeiros CB, Barrett JA, Dudin A, Cunningham WA, Hall GB, et al. Postpartum depression and brain response to infants: differential amygdala response and connectivity. Soc Neurosci. 2016;11(6):600–17. This study used fMRI to evaluate amygdala response to positive stimuli and demonstrated that there is overall increased right amygdala response and decreased amygdala-right insular cortex connectivity in PPD women compared to healthy postpartum women. This is also the first report of altered response and functional connectivity in mothers by parity status.

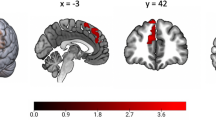

•• Chase HW, Moses-Kolko EL, Zevallos C, Wisner KL, Phillips ML. Disrupted posterior cingulate-amygdala connectivity in postpartum depressed women as measured with resting BOLD fMRI. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9(8):1069–75. This study examined resting-state functional connectivity in postpartum women and found that posterior cingulate cortex-right amygdala connectivity was significantly disrupted in depressed compared to healthy mothers.

•• Sacher J, Wilson AA, Houle S, Rusjan P, Hassan S, Bloomfield PM, et al. Elevated brain monoamine oxidase A binding in the early postpartum period. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):468–74. This study examined brain MAO-A total distribution volume in the early postpartum period and reported that mean distribution volume was significantly elevated throughout several areas analyzed.

Sacher J, Rekkas PV, Wilson AA, Houle S, Romano L, Hamidi J, et al. Relationship of monoamine oxidase-A distribution volume to postpartum depression and postpartum crying. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(2):429–35.

•• Moses-Kolko EL, Price JC, Wisner KL, Hanusa BH, Meltzer CC, Berga SL, et al. Postpartum and depression status are associated with lower [[(1)(1)C]raclopride BP(ND) in reproductive-age women. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(6):1422–32. This study used PET scans with carbon-11 raclopride to demonstrate that D2/3 receptor binding is decreased in both unipolar depressed patients and postpartum patients regardless of depressive status with no difference in D2/3 receptor binding between PPD women and healthy postpartum women.

Moses-Kolko EL, Wisner KL, Price JC, Berga SL, Drevets WC, Hanusa BH, et al. Serotonin 1A receptor reductions in postpartum depression: a positron emission tomography study. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(3):685–92.

Epperson CN, Gueorguieva R, Czarkowski KA, Stiklus S, Sellers E, Krystal JH, et al. Preliminary evidence of reduced occipital GABA concentrations in puerperal women: a 1H-MRS study. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186(3):425–33.

McEwen AM, Burgess DT, Hanstock CC, Seres P, Khalili P, Newman SC, et al. Increased glutamate levels in the medial prefrontal cortex in patients with postpartum depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(11):2428–35.

Kim P, Strathearn L, Swain JE. The maternal brain and its plasticity in humans. Horm Behav. 2016;77:113–23.

Drevets WC, Price JL, Furey ML. Brain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: implications for neurocircuitry models of depression. Brain Struct Funct. 2008;213(1–2):93–118.

Fu CH, Williams SC, Cleare AJ, Brammer MJ, Walsh ND, Kim J, et al. Attenuation of the neural response to sad faces in major depression by antidepressant treatment: a prospective, event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):877–89.

Siegle GJ, Steinhauer SR, Thase ME, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Can’t shake that feeling: event-related fMRI assessment of sustained amygdala activity in response to emotional information in depressed individuals. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(9):693–707.

Sheline YI, Barch DM, Donnelly JM, Ollinger JM, Snyder AZ, Mintun MA. Increased amygdala response to masked emotional faces in depressed subjects resolves with antidepressant treatment: an fMRI study. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50(9):651–8.

•• Barrett J, Wonch KE, Gonzalez A, Ali N, Steiner M, Hall GB, et al. Maternal affect and quality of parenting experiences are related to amygdala response to infant faces. Soc Neurosci. 2012;7(3):252–68. This is the first study to use fMRI activation patterns as a function of the affect of an infant face and found that poor quality of maternal experience is significantly correlated to reduced amygdala response to own compared to other positive infant faces.

Swain JE, Lorberbaum JP. Imaging the human parental brain. Burlington: Academic Press; 2008. p. 584.

Stuhrmann A, Dohm K, Kugel H, Zwanzger P, Redlich R, Grotegerd D, et al. Mood-congruent amygdala responses to subliminally presented facial expressions in major depression: associations with anhedonia. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2013;38(4):249–58.

Gu X, Hof PR, Friston KJ, Fan J. Anterior insular cortex and emotional awareness. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521(15):3371–88.

Paulus MP, Stein MB. An insular view of anxiety. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):383–7.

Wenzel A, Haugen EN, Jackson LC, Brendle JR. Anxiety symptoms and disorders at eight weeks postpartum. J Anxiety Disord. 2005;19(3):295–311.

Britton JR. Maternal anxiety: course and antecedents during the early postpartum period. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(9):793–800.

Anand A, Li Y, Wang Y, Wu J, Gao S, Bukhari L, et al. Activity and connectivity of brain mood regulating circuit in depression: a functional magnetic resonance study. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(10):1079–88.

Greicius MD, Flores BH, Menon V, Glover GH, Solvason HB, Kenna H, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity in major depression: abnormally increased contributions from subgenual cingulate cortex and thalamus. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(5):429–37.

Veer IM, Beckmann CF, Baerends E, van Tol MJ, Ferrarini L, Milles JR, et al. Reduced functional connectivity in major depression: a whole brain study of multiple resting-state networks. NeuroImage. 2009;47(Supplement 1):S70.

Andrews-Hanna JR. The brain’s default network and its adaptive role in internal mentation. Neuroscientist. 2012;18(3):251–70.

Sheline YI, Price JL, Yan Z, Mintun MA. Resting-state functional MRI in depression unmasks increased connectivity between networks via the dorsal nexus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(24):11020–5.

Leech R, Sharp DJ. The role of the posterior cingulate cortex in cognition and disease. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 1):12–32.

Phelps EA, LeDoux JE. Contributions of the amygdala to emotion processing: from animal models to human behavior. Neuron. 2005;48(2):175–87.

Placzek MS, Zhao W, Wey HY, Morin TM, Hooker JM. PET neurochemical imaging modes. Semin Nucl Med. 2016;46(1):20–7.

Gaweska H, Fitzpatrick PF. Structures and mechanism of the monoamine oxidase family. Biomol Concepts. 2011;2(5):365–77.

Harmer CJ, Duman RS, Cowen PJ. How do antidepressants work? New perspectives for refining future treatment approaches. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017.

Meyer JH, Ginovart N, Boovariwala A, Sagrati S, Hussey D, Garcia A, et al. Elevated monoamine oxidase a levels in the brain: an explanation for the monoamine imbalance of major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(11):1209–16.

Chevillard C, Barden N, Saavedra JM. Estradiol treatment decreases type A and increases type B monoamine oxidase in specific brain stem areas and cerebellum of ovariectomized rats. Brain Res. 1981;222(1):177–81.

Bergstrom M, Westerberg G, Langstrom B. 11C-harmine as a tracer for monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A): in vitro and in vivo studies. Nucl Med Biol. 1997;24(4):287–93.

Dunlop BW, Nemeroff CB. The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):327–37.

Hall H, Kohler C, Gawell L, Farde L, Sedvall G. Raclopride, a new selective ligand for the dopamine-D2 receptors. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1988;12(5):559–68.

Gurevich EV, Joyce JN. Distribution of dopamine D3 receptor expressing neurons in the human forebrain: comparison with D2 receptor expressing neurons. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20(1):60–80.

Fornal CA, Metzler CW, Gallegos RA, Veasey SC, McCreary AC, Jacobs BL. WAY-100635, a potent and selective 5-hydroxytryptamine1A antagonist, increases serotonergic neuronal activity in behaving cats: comparison with (S)-WAY-100135. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278(2):752–62.

Wang L, Zhou C, Zhu D, Wang X, Fang L, Zhong J, et al. Serotonin-1A receptor alterations in depression: a meta-analysis of molecular imaging studies. BMC Psychiat. 2016;16(1):319.

Rao NP, Venkatasubramanian G, Gangadhar BN. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in depression. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53(4):307–11.

Merritt K, Egerton A, Kempton MJ, Taylor MJ, McGuire PK. Nature of glutamate alterations in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. JAMA psychiat. 2016;73(7):665–74.

Schur RR, Draisma LW, Wijnen JP, Boks MP, Koevoets MG, Joels M, et al. Brain GABA levels across psychiatric disorders: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of (1) H-MRS studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37(9):3337–52.

Wang W, Hu Y, Lu P, Li Y, Chen Y, Tian M, et al. Evaluation of the diagnostic performance of magnetic resonance spectroscopy in brain tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112577.

Oz G, Alger JR, Barker PB, Bartha R, Bizzi A, Boesch C, et al. Clinical proton MR spectroscopy in central nervous system disorders. Radiology. 2014;270(3):658–79.

Holdcroft A, Hall L, Hamilton G, Counsell SJ, Bydder GM, Bell JD. Phosphorus-31 brain MR spectroscopy in women during and after pregnancy compared with nonpregnant control subjects. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(2):352–6.

Sanacora G, Treccani G, Popoli M. Towards a glutamate hypothesis of depression: an emerging frontier of neuropsychopharmacology for mood disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(1):63–77.

Hasler G, van der Veen JW, Tumonis T, Meyers N, Shen J, Drevets WC. Reduced prefrontal glutamate/glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid levels in major depression determined using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(2):193–200.

Rosa C, Soares J, Figueiredo F, Cavalli R, Barbieri M, Spanghero M, et al. Glutamatergic and neural dysfunction in postpartum depression using magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging. 2017;265:18–25.

Wise T, Radua J, Nortje G, Cleare AJ, Young AH, Arnone D. Voxel-based meta-analytical evidence of structural disconnectivity in major depression and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):293–302.

Redlich R, Almeida JJ, Grotegerd D, Opel N, Kugel H, Heindel W, et al. Brain morphometric biomarkers distinguishing unipolar and bipolar depression. A voxel-based morphometry-pattern classification approach. JAMA Psychiat. 2014;71(11):1222–30.

Videbech P, Ravnkilde B. Hippocampal volume and depression: a meta-analysis of MRI studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):1957–66.

Schiller CE, Meltzer-Brody S, Rubinow DR. The role of reproductive hormones in postpartum depression. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(1):48–59.

Altemus M, Fong J, Yang R, Damast S, Luine V, Ferguson D. Changes in cerebrospinal fluid neurochemistry during pregnancy. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(6):386–92.

Deligiannidis KM, Kroll-Desrosiers AR, Mo S, Nguyen HP, Svenson A, Jaitly N, et al. Peripartum neuroactive steroid and gamma-aminobutyric acid profiles in women at-risk for postpartum depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;70:98–107.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following: Janice Lester, MLS; Reference and Education Librarian; Health Science Library; Long Island Jewish Medical Center; Northwell Health.

Role of the Funding Source

This manuscript was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant (5K23MH097794). Dr. Deligiannidis currently receives funding from the National Institutes of Health and SAGE Therapeutics and receives royalties from an NIH Employee Invention. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Christy Duan and Jessica Cosgrove each declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Kristina M. Deligiannidis reports a research grant from the National Institutes of Health.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Reproductive Psychiatry and Women’s Health

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Duan, C., Cosgrove, J. & Deligiannidis, K.M. Understanding Peripartum Depression Through Neuroimaging: a Review of Structural and Functional Connectivity and Molecular Imaging Research. Curr Psychiatry Rep 19, 70 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0824-4

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0824-4