Abstract

In this review, we present a summary of some of the most pertinent new research on aspects of apraxia. Rather than attempt a review of all neurologic syndromes that have been identified as forms of apraxia, such as buccofacial, truncal, apraxia of eye opening, and apraxia of speech, we focus on current literature and trends in the study of limb apraxia. Although the classic empirical approach to the study of apraxia has been through systematic neuropsychologic assessment of various aspects of the syndrome, questions remain regarding the exact neural substrate that forms the foundation of the praxis system. More recent work using sophisticated neuroimaging methods has yielded a wealth of new data that contributes significantly to our understanding of the neuroanatomic correlates of this complex disorder. In addition, the results of recent sophisticated neuropsychologic studies have suggested modifications to classic cognitive models of apraxia. A discussion of current work and directions for future research are also provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

Liepmann H: Die linke Hemisphere und das Handeln. Muenchner Medizinische Wochesnschrift 1905, 49:2322–2326, 2375–2378.

Liepmann H: Apraxie. Ergebnisse der Gesamten Medzin 1920, 1:516–543.

Geschwind N: Disconnection syndromes in animals and man. Brain 1965, 88:237–294.

Heilman KM, Rothi LJ, Valenstein E: Two forms of ideomotor apraxia. Neurology 1982, 32:342–346.

Rothi LJ, Heilman KM, Watson RT: Pantomime comprehension and ideomotor apraxia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1982, 4:207–210.

Bartolo A, Cubelli R, Della Sala S, Drei S: Pantomimes are special gestures which rely on working memory. Brain Cogn 2003, 53:483–494. The authors provide evidence to support the addition of a working memory "workspace" to cognitive models of apraxia, which allows for online processing of information specific to gesture production.

Goldenberg G: Pantomime of object use: a challenge to cerebral localization of cognitive function. NeuroImage 2003, 20:S101-S106.

Liepmann H: Drei Aufsätze aus dem Apraxiegebiet. Berlin: Karger; 1908.

Finkelnberg FC: Sitzung der niederrheinischen gesellschaft in Bonn. Medizinische Section, Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift 1870, 7:449–450; 460–462.

Joshi A, Roy EA, Black SE, Barbour K: Patterns of limb apraxia in primary progressive aphasia. Brain Cogn 2003, 53:403–407.

Hamilton JM, Haaland KY, Adair JC, Brandt J: Ideomotor limb apraxia in Huntington’s disease: implications for corticostriate involvement. Neuropsychologia 2003, 41:614–621.

Heiser M, Iacoboni M, Maeda F, et al.: The essential role of Broca’s area in imitation. Eur J Neurosci 2003, 17:1123–1128.

Hanna-Pladdy B, Heilman KM, Foundas AL: Ecological implications of ideomotor apraxia: evidence from physical activities of daily living. Neurology 2003, 60:487–490.

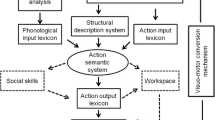

Rothi LJ, Ochipa C, Heilman KM: A cognitive neuropsychological model of limb praxis. Cogn Neuropsychol 1991, 8:443–458.

Peigneux P, Van der Linden M, Garraux G, et al.: Imaging a cognitive model of apraxia: the neural substrate of gesture-specific cognitive processes. Hum Brain Mapp 2004, 21:119–142. Specific neural components of Rothi et al.’s [16] 1997 neuropsychologic model of the apraxia system were visualized using PET. The authors suggest one single memory store for information about familiar gestures, in contrast to the input and output praxicon components proposed in the original model.

Rothi LJ, Ochipa C, Heilman KM: A cognitive neuropsychological model of limb praxis. In Apraxia: The Neuropsychology of Action. Edited by Rothi LJ, Heilman KM. Hove, England: Psychology Press; 1997:29–50.

Rizzolatti G, Luppino G, Matelli M: The organization of the cortical motor system: new concepts. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1998, 106:283–296.

Rizzolatti G, Fadiga L, Matelli M, et al.: Localization of grasp representation in human by PET: 1. Observation versus execution. Exp Brain Res 1996, 111:246–252.

Hamzei F, Rijntjes M, Dettmers C, et al.: The human action recognition system and its relationship to Broca’s area: an fMRI study. Neuroimage 2003, 19:637–644. Activation of the inferior frontal gyrus in both verb generation and action recognition tasks suggests a common neuroanatomic substrate for these functions.

Rizzolatti G, Arbib MA: Language within our grasp. Trends Neurosci 1998, 21:188–194.

Kellenbach ML, Brett M, Patterson K: Actions speak louder than functions: the importance of manipulability and action in tool representation. J Cogn Neurosci 2003, 15:30–46. This PET study demonstrated significant increase in rCBF in left ventral premotor cortex and posterior middle temporal gyrus on a task requiring judgments about actions associated with tools versus judgments about the tasks for which they are used. The results suggest preferential processing of "how" versus "what" information in these brain regions strongly associated with praxis functioning.

Buxbaum LJ, Veramonti T, Schwartz MF: Function and manipulation tool knowledge in apraxia: knowing "what for" but not "how". Neurocase 2000, 6:83–97.

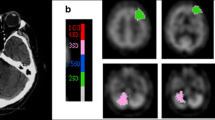

Rumiati RI, Weiss PH, Shallice T, et al.: Neural basis of pantomiming the use of visually presented objects. NeuroImage 2004, 21:1224–1231.

Buxbaum LJ, Sirigu A, Schwartz MF, Klatzky R: Cognitive representations of hand posture in ideomotor apraxia. Neuropsychologia 2003, 41:1091–1113.

Marshall JC, Fink GR: Spatial cognition: where we were and where we are. NeuroImage 2001, 14:S2-S7.

Coull JT, Nobre AC: Where and when to pay attention: the neural systems for directing attention to spatial locations and to time intervals as revealed by both PET and fMRI. J Neurosci 1988, 18:7426–7435.

Foundas AL, Henchey MD, Gilmore MD, et al.: Apraxia during Wada testing. Neurology 1995, 45:1379–1383.

Assmus A, Marshall JC, Ritzl A, et al.: Left inferior parietal cortex integrates time and space during collision judgments. NeuroImage 2003, 20:S82-S88.

Foundas AL, Macauley BL, Raymer AM, et al.: Ecological implications of limb apraxia: evidence from mealtime behavior. J Int Neuropsychol Soci 1995, 1:62–66.

Smania N, Girardi F, Domenicali C, et al.: The rehabilitation of limb apraxia: a study in left-brain damaged patients. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2000, 81:379–388.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McClain, M., Foundas, A. Apraxia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 4, 471–476 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-004-0071-z

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-004-0071-z