Abstract

Purpose of Review

To review the data supporting the use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM), and to provide practical guidance for practitioners who are establishing an ambulatory monitoring service.

Recent Findings

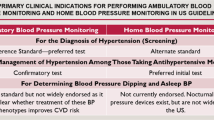

ABPM results more accurately reflect the risk of cardiovascular events than do office measurements of blood pressure. Moreover, many patients with high blood pressure in the office have normal blood pressure on ABPM—a pattern known as white coat hypertension—and have a prognosis similar to individuals who are normotensive in both settings. For these reasons, ABPM is recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension in patients with high office blood pressure before medical therapy is initiated. Similarly, the 2017 ACC/AHA High Blood Pressure Clinical Practice Guideline advocates the use of out-of-office blood pressure measurements to confirm hypertension and evaluate the efficacy of blood pressure-lowering medications. In addition to white coat hypertension, blood pressure phenotypes that are associated with increased cardiovascular risk and that can be recognized by ABPM include masked hypertension—characterized by normal office blood pressure but high values on ABPM—and high nocturnal blood pressure. In this review, best practices for starting a clinical ABPM service, performing an ABPM monitoring session, and interpreting and reporting ABPM data are described.

Summary

ABPM is a valuable adjunct to careful office blood pressure measurement in diagnosing hypertension and in guiding antihypertensive therapy. Following recommended best practices can facilitate implementation of ABPM into clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065. This comprehensive guideline statement, which will have a major influence on the evaluation and management of hypertension in the USA, emphasizes the importance of out-of-office blood pressure measurement in establishing the diagnosis of hypertension and in assessing the effects of therapy.

National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. National Center for Health Statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/physician-visits.htm.

Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988-2008. JAMA. 2010;303:2043–50.

Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, Ng M, Biryukov S, Marczak L, et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mmHg, 1990–2015. JAMA. 2017;317:165–82.

Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005;111:697–716.

McKay DW, Raju MK, Campbell NR. Assessment of blood pressure measuring techniques. Med Educ. 1992;26:208–12.

Powers BJ, Olsen MK, Smith VA, Woolson RF, Bosworth HB, Oddone EZ. Measuring blood pressure for decision making and quality reporting: where and how many measures? Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:781–8. NaN-289–90

Fagard RH, Van Den Broeke C, De Cort P. Prognostic significance of blood pressure measured in the office, at home and during ambulatory monitoring in older patients in general practice. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:801–7.

Ohkubo T, Imai Y, Tsuji I, Nagai K, Kato J, Kikuchi N, et al. Home blood pressure measurement has a stronger predictive power for mortality than does screening blood pressure measurement: a population-based observation in Ohasama. Japan J Hypertens. 1998;16:971–5.

Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Obara T, Metoki H, Inoue R, et al. Prediction of stroke by home “morning” versus “evening” blood pressure values: the Ohasama study. Hypertens (Dallas, Tex. 1979). 2006;48:737–43.

Niiranen TJ, Hänninen M-R, Johansson J, Reunanen A, Jula AM. Home-measured blood pressure is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular risk than office blood pressure: the Finn-Home study. Hypertens (Dallas, Tex. 1979). 2010;55:1346–51.

Dolan E, Stanton A, Thijs L, Hinedi K, Atkins N, McClory S, et al. Superiority of ambulatory over clinic blood pressure measurement in predicting mortality: the Dublin outcome study. Hypertens (Dallas, Tex. 1979). 2005;46:156–61.

Gasowski J, Li Y, Kuznetsova T, Richart T, Thijs L, Grodzicki T, et al. Is “usual” blood pressure a proxy for 24-h ambulatory blood pressure in predicting cardiovascular outcomes? Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:994–1000.

Clement DL, De Buyzere ML, De Bacquer DA, de Leeuw PW, Duprez DA, Fagard RH, et al. Prognostic value of ambulatory blood-pressure recordings in patients with treated hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2407–15.

Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Mojón A, Fernández JR. Decreasing sleep-time blood pressure determined by ambulatory monitoring reduces cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1165–73.

Mesquita-Bastos J, Bertoquini S, Polónia J. Cardiovascular prognostic value of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in a Portuguese hypertensive population followed up for 8.2 years. Blood Press Monit. 2010;15:240–6.

Staessen JA, Thijs L, Fagard R, O’Brien ET, Clement D, de Leeuw PW, et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk using conventional vs ambulatory blood pressure in older patients with systolic hypertension. Systolic hypertension in Europe trial investigators. JAMA. 1999;282:539–46.

•• Siu AL, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:778–86. This statement from the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends out-of-office blood pressure monitoring to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension before starting treatment. ABPM is recognized as the best method for diagnosing hypertension.

Krause T, Lovibond K, Caulfield M, McCormack T, Williams B. Management of hypertension: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2011;343:d4891–1.

•• O’Brien E, Parati G, Stergiou G, Asmar R, Beilin L, Bilo G, et al. European Society of Hypertension position paper on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2013;31:1731–68. This position paper is a comprehensive review of ABPM, describing devices and software, procedures, indications for monitoring, and strategies for implementation.

Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, Mann S, Lindholm LH, Kenerson JG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:14–26.

Leung AA, Daskalopoulou SS, Dasgupta K, McBrien K, Butalia S, Zarnke KB, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2017 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:557–76.

Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, Artinian NT, Bakris G, Brown AS, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on clinical expert consensus documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2037–114.

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–219.

Viera AJ, Lingley K, Hinderliter AL. Tolerability of the Oscar 2 ambulatory blood pressure monitor among research participants: a cross-sectional repeated measures study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:59.

O’Brien E, Atkins N, Stergiou G, Karpettas N, Parati G, Asmar R, et al. European Society of Hypertension International Protocol revision 2010 for the validation of blood pressure measuring devices in adults. Blood Press Monit. 2010;15:23–38.

O’Brien E, Petrie J, Littler W, de Swiet M, Padfield PL, Altman DG, et al. An outline of the revised British hypertension society protocol for the evaluation of blood pressure measuring devices. J Hypertens. 1993;11:677–9.

Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation. Manual, electronic, or automated sphygmomanometers: AASI/AAMI SP10–2002. Arlington: Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation; 2003.

•• Parati G, Stergiou G, O’Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, Bilo G, et al. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1359–66. This is a concise summary of the important aspects of using ABPM in clinical practice.

•• Shimbo D, Abdalla M, Falzon L, Townsend RR, Muntner P. Role of ambulatory and home blood pressure monitoring in clinical practice: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:691–700. This very useful review describes both ABPM and home blood pressure monitoring.

Turner JR, Viera AJ, Shimbo D. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in clinical practice: a review. Am J Med. 2015;128:14–20.

Pickering TG, White WB, Giles TD, Black HR, Izzo JL, Materson BJ, et al. When and how to use self (home) and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2010;4:56–61.

White WB, Gulati V. Managing hypertension with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17:2.

Pickering TG, White WB, American Society of Hypertension Writing Group. ASH position paper: home and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. When and how to use self (home) and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10:850–5.

Kikuya M, Hansen TW, Thijs L, Björklund-Bodegård K, Kuznetsova T, Ohkubo T, et al. Diagnostic thresholds for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring based on 10-year cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2007;115:2145–52.

Winnicki M, Canali C, Mormino P, Palatini P. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring editing criteria: is standardization needed? Hypertension and Ambulatory Recording Venetia study (HARVEST) group. Italy Am J Hypertens. 1997;10:419–27.

Booth JN, Muntner P, Abdalla M, Diaz KM, Viera AJ, Reynolds K, et al. Differences in night-time and daytime ambulatory blood pressure when diurnal periods are defined by self-report, fixed-times, and actigraphy: improving the detection of hypertension study. J Hypertens. 2016;34:235–43.

O’Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, Imai Y, Mancia G, Mengden T, et al. Practice guidelines of the European Society of Hypertension for clinic, ambulatory and self blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2005;23:697–701.

• Ravenell J, Shimbo D, Booth JN, Sarpong DF, Agyemang C, Beatty Moody DL, et al. Thresholds for ambulatory blood pressure among African Americans in the Jackson heart study. Circulation. 2017;135:2470–80. This analysis of data from the Jackson Heart Study suggests that slightly higher ambulatory blood pressure thresholds to define hypertension may be appropriate in African-Americans.

Krause T, Lovibond K, Caulfield M, McCormack T, Williams B. Guideline Development Group. Management of hypertension: summary of NICE guidance BMJ. 2011;343:d4891.

• Franklin SS, Thijs L, Asayama K, Li Y, Hansen TW, Boggia J, et al. The cardiovascular risk of white-coat hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2033–43. This careful analysis of IDACO data found that cardiovascular risk in most persons with white-coat hypertension is comparable to age- and risk-adjusted normotensive control subjects.

Fagard RH, Staessen JA, Thijs L, Gasowski J, Bulpitt CJ, Clement D, et al. Response to antihypertensive therapy in older patients with sustained and nonsustained systolic hypertension. Systolic hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) trial investigators. Circulation. 2000;102:1139–44.

Kario K, Shimada K, Schwartz JE, Matsuo T, Hoshide S, Pickering TG. Silent and clinically overt stroke in older Japanese subjects with white-coat and sustained hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:238–45.

Khattar RS, Senior R, Lahiri A. Cardiovascular outcome in white-coat versus sustained mild hypertension: a 10-year follow-up study. Circulation. 1998;98:1892–7.

Mancia G, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Grassi G, Sega R. Long-term risk of mortality associated with selective and combined elevation in office, home, and ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertens (Dallas, Tex. 1979). 2006;47:846–53.

•• Piper MA, Evans CV, Burda BU, Margolis KL, O’Connor E, Whitlock EP. Diagnostic and predictive accuracy of blood pressure screening methods with consideration of rescreening intervals: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:192–204. This systematic review of ABPM and home blood pressure monitoring in comparison to office blood pressure provides the basis for the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation to perform out-of-office measurements to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension.

de la Sierra A, Segura J, Banegas JR, Gorostidi M, de la Cruz JJ, Armario P, et al. Clinical features of 8295 patients with resistant hypertension classified on the basis of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Hypertens (Dallas, Tex. 1979). 2011;57:898–902.

Muxfeldt ES, Bloch KV, Nogueira Ada R, Salles GF. True resistant hypertension: is it possible to be recognized in the office? Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:1534–40.

Brown MA, Buddle ML, Martin A. Is resistant hypertension really resistant? Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:1263–9.

Franklin SS, Thijs L, Hansen TW, Li Y, Boggia J, Kikuya M, et al. Significance of white-coat hypertension in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension: a meta-analysis using the International Database on Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring in Relation to Cardiovascular Outcomes population. Hypertens (Dallas, Tex. 1979). 2012;59:564–71.

Björklund K, Lind L, Zethelius B, Andrén B, Lithell H. Isolated ambulatory hypertension predicts cardiovascular morbidity in elderly men. Circulation. 2003;107:1297–302.

Hansen TW, Jeppesen J, Rasmussen S, Ibsen H, Torp-Pedersen C. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and risk of cardiovascular disease: a population based study. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:243–50.

Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Metoki H, Asayama K, Obara T, Hashimoto J, et al. Prognosis of “masked” hypertension and “white-coat” hypertension detected by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring 10-year follow-up from the Ohasama study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:508–15.

Diaz KM, Veerabhadrappa P, Brown MD, Whited MC, Dubbert PM, Hickson DA. Prevalence, determinants, and clinical significance of masked hypertension in a population-based sample of African Americans: the Jackson heart study. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:900–8.

Viera AJ, Lin F-C, Tuttle LA, Olsson E, Stankevitz K, Girdler SS, et al. Reproducibility of masked hypertension among adults 30 years or older. Blood Press Monit. 2014;19:208–15.

Salles GF, Reboldi G, Fagard RH, Cardoso CRL, Pierdomenico SD, Verdecchia P, et al. Prognostic effect of the nocturnal blood pressure fall in hypertensive patients: the Ambulatory Blood Pressure Collaboration in Patients with Hypertension (ABC-H) meta-analysis. Hypertens (Dallas, Tex. 1979). 2016;67:693–700.

Boggia J, Li Y, Thijs L, Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Björklund-Bodegård K, et al. Prognostic accuracy of day versus night ambulatory blood pressure: a cohort study. Lancet (London, England). 2007;370:1219–29.

Li Y, Thijs L, Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Boggia J, Richart T, et al. Prognostic value of the morning blood pressure surge in 5645 subjects from 8 populations. Hypertens (Dallas, Tex. 1979). 2010;55:1040–8.

Kario K, Pickering TG, Umeda Y, Hoshide S, Hoshide Y, Morinari M, et al. Morning surge in blood pressure as a predictor of silent and clinical cerebrovascular disease in elderly hypertensives: a prospective study. Circulation. 2003;107:1401–6.

Hansen TW, Thijs L, Li Y, Boggia J, Kikuya M, Björklund-Bodegård K, et al. Prognostic value of reading-to-reading blood pressure variability over 24 hours in 8938 subjects from 11 populations. Hypertens (Dallas, Tex. 1979). 2010;55:1049–57.

Hinderliter AL, Routledge FS, Blumenthal JA, Koch G, Hussey MA, Wohlgemuth WK, et al. Reproducibility of blood pressure dipping: relation to day-to-day variability in sleep quality. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2013;7:432–9.

Thijs L, Staessen J, Fagard R, Zachariah P, Amery A. Number of measurements required for the analysis of diurnal blood pressure profile. J Hum Hypertens. 1994;8:239–44.

Kent ST, Shimbo D, Huang L, Diaz KM, Viera AJ, Kilgore M, et al. Rates, amounts, and determinants of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring claim reimbursements among Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8:898–908.

Lovibond K, Jowett S, Barton P, Caulfield M, Heneghan C, Hobbs FDR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of options for the diagnosis of high blood pressure in primary care: a modelling study. Lancet (London, England). 2011;378:1219–30.

Myers MG. Automated office blood pressure—the preferred method for recording blood pressure. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016;10:194–6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Implementation to Increase Blood Pressure Control: What Works?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hinderliter, A.L., Voora, R.A. & Viera, A.J. Implementing ABPM into Clinical Practice. Curr Hypertens Rep 20, 5 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-018-0805-y

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-018-0805-y