Abstract

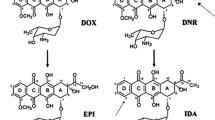

Anthracyclines are common chemotherapeutic agents used to treat many different types of cancer. Unfortunately, the use of anthracyclines is limited by their cardiotoxic effects, which may become manifest as late as 20 years from initial exposure. Studies in cells and animals suggest that the mechanism of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity (AIC) is multifactorial. Anthracyclines induce multiple forms of cellular injury by free radical production. In addition, anthracyclines alter nucleic acid biology by intercalation into DNA and modulate intracellular signaling, leading to cell death and the disruption of homeostatic processes such as sarcomere maintenance. In an effort to decrease AIC, many strategies have been tested, but no specific therapies are universally acknowledged to prevent or treat anthracycline-induced cardiac dysfunction. Newer imaging modalities and cardiac biomarkers may be useful in improving early detection of cardiac injury and dysfunction. As long as there is no cardiac-specific therapy for AIC, evidence suggests that high-risk patients will benefit from prophylactic treatment with neurohormonal blockade by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and beta-adrenergic receptor blockers.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Shankar SM, Marina N, Hudson MM, et al.: Monitoring for cardiovascular disease in survivors of childhood cancer: report from the Cardiovascular Disease Task Force of the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatrics 2008, 121:e387–e396.

Steinherz LJ, Steinherz PG, Tan CT, et al.: Cardiac toxicity 4 to 20 years after completing anthracycline therapy. JAMA 1991, 266:1672–1677.

• Cardinale D, Colombo A, Lamantia G, et al.: Anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy: clinical relevance and response to pharmacologic therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010, 55:213–220. In a prospective clinical trial, 201 patients with AIC were treated with enalapril and carvedilol promptly after diagnosis of LV ejection fraction of 45% or less. Complete recovery of the ejection fraction occurred in 85 patients (42%). The percentage of responders decreased when the time from chemotherapy to diagnosis of reduced ejection fraction was greater than 4 months.

• Lipshultz SE, Alvarez JA, Scully RE: Anthracycline associated cardiotoxicity in survivors of childhood cancer. Heart 2008, 94:525–533. A review of results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) discussing increased cumulative incidence of chronic health conditions 30 years after treatment. The review highlights proposed pathophysiology that occurs during late-onset cardiotoxicity after childhood exposure and recommendations for monitoring and treatment.

Shan K, Lincoff AM, Young JB: Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Ann Intern Med 1996, 125:47–58.

Perez EA, Suman VJ, Davidson NE, et al.: Cardiac safety analysis of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel with or without trastuzumab in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 adjuvant breast cancer trial. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26:1231–1238.

Peng X, Chen B, Lim CC, Sawyer DB: The cardiotoxicology of anthracycline chemotherapeutics: translating molecular mechanism into preventative medicine. Mol Interv 2005, 5:163–171.

Unverferth DV, Magorien RD, Unverferth BP, et al.: Human myocardial morphologic and functional changes in the first 24 hours after doxorubicin administration. Cancer Treat Rep 1981, 65:1093–1097.

Childs AC, Phaneuf SL, Dirks AJ, et al.: Doxorubicin treatment in vivo causes cytochrome C release and cardiomyocyte apoptosis, as well as increased mitochondrial efficiency, superoxide dismutase activity, and Bcl-2:Bax ratio. Cancer Res 2002, 62:4592–4598.

Lipshultz SE, Rifai N, Sallan SE, et al.: Predictive value of cardiac troponin T in pediatric patients at risk for myocardial injury. Circulation 1997, 96:2641–2648.

Horenstein MS, Vander Heide RS, L’Ecuyer TJ: Molecular basis of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity and its prevention. Mol Genet Metab 2000, 71:436–444.

Tokarska-Schlattner M, Zaugg M, Zuppinger C, et al.: New insights into doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: the critical role of cellular energetics. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2006, 41:389–405.

Sawyer DB, Fukazawa R, Arstall MA, Kelly RA: Daunorubicin-induced apoptosis in rat cardiac myocytes is inhibited by dexrazoxane. Circ Res 1999, 84:257–265.

Yen HC, Oberley TD, Vichitbandha S, et al.: The protective role of manganese superoxide dismutase against Adriamycin-induced acute cardiac toxicity in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest 1996, 98:1253–1260.

Tewey KM, Chen GL, Nelson EM, Liu LF: Intercalative antitumor drugs interfere with the breakage-reunion reaction of mammalian DNA topoisomerase II. J Biol Chem 1984, 259:9182–9187.

Liu J, Mao W, Ding B, Liang CS: ERKs/p53 signal transduction pathway is involved in doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cells and cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008, 295:H1956–H1965.

Fukazawa R, Miller TA, Kuramochi Y, et al.: Neuregulin-1 protects ventricular myocytes from anthracycline-induced apoptosis via erbB4-dependent activation of PI3-kinase/Akt. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2003, 35:1473–1479.

Zhao YY, Sawyer DR, Baliga RR, et al.: Neuregulins promote survival and growth of cardiac myocytes. Persistence of ErbB2 and ErbB4 expression in neonatal and adult ventricular myocytes. J Biol Chem 1998, 273:10261–10269.

Rohrbach S, Yan X, Weinberg EO, et al.: Neuregulin in cardiac hypertrophy in rats with aortic stenosis. Differential expression of erbB2 and erbB4 receptors. Circulation 1999, 100:407–412.

Bains OS, Takahashi RH, Pfeifer TA, et al.: Two allelic variants of aldo-keto reductase 1A1 exhibit reduced in vitro metabolism of daunorubicin. Drug Metab Dispos 2008, 36:904–910.

Wojnowski L, Kulle B, Schirmer M, et al.: NAD(P)H oxidase and multidrug resistance protein genetic polymorphisms are associated with doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Circulation 2005, 112:3754–3762.

Deng S, Wojnowski L: Genotyping the risk of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2007, 7:129–134.

Charron F, Nemer M: GATA transcription factors and cardiac development. Semin Cell Dev Biol 1999, 10:85–91.

O’Prey J, Ramsay S, Chambers I, Harrison PR: Transcriptional up-regulation of the mouse cytosolic glutathione peroxidase gene in erythroid cells is due to a tissue-specific 3′ enhancer containing functionally important CACC/GT motifs and binding sites for GATA and Ets transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol 1993, 13:6290–6303.

Jeyaseelan R, Poizat C, Baker RK, et al.: A novel cardiac-restricted target for doxorubicin. CARP, a nuclear modulator of gene expression in cardiac progenitor cells and cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:22800–22808.

Saadane N, Alpert L, Chalifour LE: TAFII250, Egr-1, and D-type cyclin expression in mice and neonatal rat cardiomyocytes treated with doxorubicin. Am J Physiol 1999, 276:H803–814.

Chen S, Garami M, Gardner DG: Doxorubicin selectively inhibits brain versus atrial natriuretic peptide gene expression in cultured neonatal rat myocytes. Hypertension 1999, 34:1223–1231.

Granzier H, Wu Y, Siegfried L, LeWinter M: Titin: physiological function and role in cardiomyopathy and failure. Heart Fail Rev 2005, 10:211–223.

Lim CC, Zuppinger C, Guo X, et al.: Anthracyclines induce calpain-dependent titin proteolysis and necrosis in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem 2004, 279:8290–8299.

De Angelis A, Piegari E, Cappetta D, et al.: Anthracycline cardiomyopathy is mediated by depletion of the cardiac stem cell pool and is rescued by restoration of progenitor cell function. Circulation 2010, 121:276–292.

Huang C, Zhang X, Ramil JM, et al.: Juvenile exposure to anthracyclines impairs cardiac progenitor cell function and vascularization resulting in greater susceptibility to stress-induced myocardial injury in adult mice. Circulation 2010, 121:675–683.

Lipshultz SE, Giantris AL, Lipsitz SR, et al.: Doxorubicin administration by continuous infusion is not cardioprotective: the Dana-Farber 91-01 Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia protocol. J Clin Oncol 2002, 20:1677–1682.

Ewer MS, Martin FJ, Henderson C, et al.: Cardiac safety of liposomal anthracyclines. Semin Oncol 2004, 31(6 Suppl 13):161–181.

van Dalen EC, Michiels EM, Caron HN, Kremer LC: Different anthracycline derivates for reducing cardiotoxicity in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010, 5:CD005006.

van Dalen EC, Caron HN, Dickinson HO, Kremer LC: Cardioprotective interventions for cancer patients receiving anthracyclines. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005, 1:CD003917.

Kapusta L, Groot-Loonen J, Thijssen JM, et al.: Regional cardiac wall motion abnormalities during and shortly after anthracyclines therapy. Med Pediatr Oncol 2003, 41:426–435.

Tassan-Mangina S, Codorean D, Metivier M, et al.: Tissue Doppler imaging and conventional echocardiography after anthracycline treatment in adults: early and late alterations of left ventricular function during a prospective study. Eur J Echocardiogr 2006, 7:141–146.

Walker J, Bhullar N, Fallah-Rad N, et al.: Role of three-dimensional echocardiography in breast cancer: comparison with two-dimensional echocardiography, multiple-gated acquisition scans, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol 2010, 28:3429–3436.

Daugaard G, Lassen U, Bie P, et al.: Natriuretic peptides in the monitoring of anthracycline induced reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2005, 7:87–93.

• Cil T, Kaplan AM, Altintas A, et al.: Use of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide to assess left ventricular function after adjuvant doxorubicin therapy in early breast cancer patients: a prospective series. Clin Drug Investig 2009, 29:131–137. In a prospective study, 33 patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer undergoing a total dose of doxorubicin of 240 mg/m 2 were monitored for changes in ejection fraction and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). A significant association was found between high NT-proBNP and reduced ejection fraction.

Felker GM, Thompson RE, Hare JM, et al.: Underlying causes and long-term survival in patients with initially unexplained cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2000, 342:1077–1084.

Silber JH, Cnaan A, Clark BJ, et al.: Enalapril to prevent cardiac function decline in long-term survivors of pediatric cancer exposed to anthracyclines. J Clin Oncol 2004, 22:820–828.

Bristow MR: Mechanism of action of beta-blocking agents in heart failure. Am J Cardiol 1997, 80:26 L–40 L.

Kalay N, Basar E, Ozdogru I, et al.: Protective effects of carvedilol against anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006, 48:2258–2262.

Tokudome T, Mizushige K, Noma T, et al.: Prevention of doxorubicin (Adriamycin)-induced cardiomyopathy by simultaneous administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor assessed by acoustic densitometry. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2000, 36:361–368.

Riad A, Bien S, Westermann D, et al.: Pretreatment with statin attenuates the cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin in mice. Cancer Res 2009, 69:695–699.

Kim KH, Oudit GY, Backx PH: Erythropoietin protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy via a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2008, 324:160–169.

Bohlius J, Langensiepen S, Schwarzer G, et al.: Recombinant human erythropoietin and overall survival in cancer patients: results of a comprehensive meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005, 97:489–498.

Sayed-Ahmed MM, Khattab MM, Gad MZ, Osman AM: Increased plasma endothelin-1 and cardiac nitric oxide during doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Pharmacol Toxicol 2001, 89:140–144.

Bien S, Riad A, Ritter CA, et al.: The endothelin receptor blocker bosentan inhibits doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Cancer Res 2007, 67:10428–10435.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Geisberg is supported by a fellowship from the Heart Failure Society of America. Dr. Sawyer is supported by an Established Investigator Award from the American Heart Association, as well as NIH R01 HL068144.

Disclosure

Dr. D. Sawyer has received payments (part of licensing fees paid by Zensun) related to his role as a coinventor of recombinant neuregulin for the treatment of heart failure. He is currently receiving grant support from Acorda Therapeutics related to the development of recombinant neuregulin. Dr. C. Geisberg reports no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Geisberg, C.A., Sawyer, D.B. Mechanisms of Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity and Strategies to Decrease Cardiac Damage. Curr Hypertens Rep 12, 404–410 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-010-0146-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-010-0146-y