Abstract

Purpose of Review

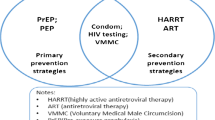

Evidence from clinical trials identified the effectiveness of voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) as an additional strategy to reduce the risk of HIV transmission from women to men. However, concerns about post-circumcision sexual risk compensation may hinder the scale-up of VMMC programs. We reviewed the evidence of changes in risky sexual behaviors after circumcision, including condomless sex, multiple sex partners, and early resumption of sex after surgery.

Recent Findings

Most clinical trial data indicate that condomless sex and multiple partners did not increase for men after circumcision, and early resumption of sex is rare. Only one post-trial surveillance reports that some circumcised men had more sex partners after surgery, but this did not offset the effect of VMMC. Conversely, qualitative studies report that a small number of circumcised men had increased risky sexual behaviors, and community-based research reports that more men resumed sex early after surgery.

Summary

With the large-scale promotion and expansion of VMMC services, it may be challenging to maintain effective sexual health educations due to various restrictions. Misunderstandings of the effect of VMMC in preventing HIV infection are the main reason for increasing risky sexual behaviors after surgery. Systematic and practical sexual health counseling services should be in place on an ongoing basis to maximize the effect of VMMC.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Weiss HA, Hankins CA, Dickson K. Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(11):669–77.

Auvert B, et al. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005;2(11):e298.

Bailey RC, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):643–56.

Gray RH, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet (london, england). 2007;369(9562):657–66.

Cassell MM, et al. Risk compensation: the Achilles’ heel of innovations in HIV prevention? BMJ. 2006;332(7541):605–7.

Clinical VMMC Wound Healing Expert Committee. Wound healing after voluntary medical male circumcision. Clearinghouse on Male Circumcision for HIV prevention. July 27, 2014. (www.malecircumcision.org/research/documents/definition_wound_healing_after_VMMC.pdf. accessed 28 December 2021).

Mukudu H, et al. Voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) for prevention of heterosexual transmission of HIV and risk compensation in adult males in Soweto: findings from a programmatic setting. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(3):e0213571.

Feldblum PJ, et al. Longer-term follow-up of Kenyan men circumcised using the ShangRing device. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0137510.

Gray R, et al. The effectiveness of male circumcision for HIV prevention and effects on risk behaviors in a posttrial follow-up study. AIDS. 2012;26(5):609–15.

Kong X, et al. Assessment of changes in risk behaviors during 3 years of posttrial follow-up of male circumcision trial participants uncircumcised at trial closure in Rakai. Uganda Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(10):875–85.

Westercamp N, et al. Risk compensation following male circumcision: results from a two-year prospective cohort study of recently circumcised and uncircumcised men in Nyanza Province. Kenya AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1764–75.

Kagaayi J, et al. Self-selection of male circumcision clients and behaviors following circumcision in a service program in Uganda. AIDS. 2016;30(13):2125–9.

Govender K, et al. Risk compensation following medical male circumcision: results from a 1-year prospective cohort study of young school-going men in KwaZulu-Natal. South Africa Int J Behav Med. 2018;25(1):123–30.

Kabwama SN, Ssewanyana D, Berg-Beckhoff G. The association between male circumcision and condom use behavior - a meta-analysis. Mater Sociomed. 2018;30(1):62–6. This meta-analysis shows VMMC did not influence condom use behavior in the medium and short term.

Gao Y, et al. Association between medical male circumcision and HIV risk compensation among heterosexual men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(7):e932–41. This 2021 meta-analysis shows that VMMC was not associated with increased condomless sex or multiple sex partners among heterosexual men.

Andersson KM, Owens DK, Paltiel AD. Scaling up circumcision programs in Southern Africa: the potential impact of gender disparities and changes in condom use behaviors on heterosexual HIV transmission. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(5):938–48. A model was developed to examine the dynamic interaction between reduced susceptibility to HIV infection and condom use by circumcised men.

L’Engle K, et al. Understanding partial protection and HIV risk and behavior following voluntary medical male circumcision rollout in Kenya. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(1):122–30.

Grund JM, Hennink MM. A qualitative study of sexual behavior change and risk compensation following adult male circumcision in urban Swaziland. AIDS Care. 2012;24(2):245–51.

Riess TH, et al. “When I was circumcised I was taught certain things”: risk compensation and protective sexual behavior among circumcised men in Kisumu, Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(8):e12366.

Ledikwe JH, et al. Voluntary medical male circumcision and perceived sexual functioning, satisfaction, and risk behavior: a qualitative study in Botswana. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49(3):983–98.

Kibira SPS, et al. “Now that you are circumcised, you cannot have first sex with your wife”: post circumcision sexual behaviours and beliefs among men in Wakiso district, Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21498.

Nevin, P.E., et al., Perceptions of HIV and safe male circumcision in high HIV prevalence fishing communities on lake Victoria, Uganda. PLoS ONE, 2015. 10(12).

Humphries H, et al. ‘If you are circumcised, you are the best’: understandings and perceptions of voluntary medical male circumcision among men from KwaZulu-Natal. South Africa Cult Health Sex. 2015;17(7):920–31.

Chikutsa A, Maharaj P. Social representations of male circumcision as prophylaxis against HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:603.

Mbonye M, et al. Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in fishing communities in Uganda: the influence of local beliefs and practice. Afr J AIDS Res. 2016;15(3):211–8.

Layer, E.H., et al., ‘He is proud of my courage to ask him to be circumcised’: experiences of female partners of male circumcision clients in Iringa region, Tanzania. Cult Health Sex, 2014.

Abbott SA, et al. Female sex workers, male circumcision and HIV: a qualitative study of their understanding, experience, and HIV risk in Zambia. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e53809.

Agot KE, et al. Male circumcision in Siaya and Bondo Districts, Kenya: prospective cohort study to assess behavioral disinhibition following circumcision. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(1):66–70. The first prospective cohort study detailed assessment of risk compensation following circumcision.

Alsallaq RA, et al. Quantitative assessment of the role of male circumcision in HIV epidemiology at the population level. Epidemics. 2009;1(3):139–52. Mathematical modeling to assess the role of VMMC in HIV epidemiology at the population level.

Kibira SP, et al. Exploring drivers for safe male circumcision: experiences with health education and understanding of partial HIV protection among newly circumcised men in Wakiso, Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0175228.

Mukama, T., et al., Perceptions about medical male circumcision and sexual behaviours of adults in rural Uganda: a cross sectional study. Pan African Medical Journal, 2015. 22.

Kibira, S.P.S., et al., “Now that you are circumcised, you cannot have first sex with your wife”: post circumcision sexual behaviours and beliefs among men in Wakiso district, Uganda: Post. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 2017. 20(1).

Kigozi G, et al. The safety of adult male circumcision in HIV-infected and uninfected men in Rakai, Uganda. PLoS Med. 2008;5(6):e116.

Mehta SD, et al. Does sex in the early period after circumcision increase HIV-seroconversion risk? Pooled analysis of adult male circumcision clinical trials. AIDS. 2009;23(12):1557–64. Pooled analysis of adult male circumcision clinical trials shows that early sex after circumcision was not associated with HIV risk.

Hallett TB, et al. Will circumcision provide even more protection from HIV to women and men? New estimates of the population impact of circumcision interventions. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(2):88–93.

Hewett PC, et al. Sex with stitches: assessing the resumption of sexual activity during the postcircumcision wound-healing period. AIDS. 2012;26(6):749–56.

Odeny TA, et al. Effect of text messaging to deter early resumption of sexual activity after male circumcision for HIV prevention: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(2):e50–7.

Pintye J, et al. Early resumption of sex after voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention within a programmatic delivery setting in Botswana. Int J STD AIDS. 2019;30(13):1275–83.

Odoyo-June, E., et al., Factors associated with resumption of sex before complete wound healing in circumcised HIV-positive and HIV-negative men in Kisumu, Kenya. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 2012.

Herman-Roloff A, Bailey RC, Agot K. Factors associated with the early resumption of sexual activity following medical male circumcision in Nyanza province. Kenya AIDS Behav. 2012;16(5):1173–81.

Klausner JD, et al. Is male circumcision as good as the HIV vaccine we’ve been waiting for?. Futur HIV Ther. 2008;2(1):1–7.

Kelly, A., et al., “Now we are in a different time; various bad diseases have come.” Understanding men’s acceptability of male circumcision for HIV prevention in a moderate prevalence setting. BMC public health, 2012. 12: p. 67.

Haberland NA, et al. Women’s perceptions and misperceptions of male circumcision: a mixed methods study in Zambia. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0149517.

Peltzer K, et al. HIV risk reduction intervention among medically circumcised young men in South Africa: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Med. 2012;19(3):336–41.

Pintye J, Baeten JM. Benefits of male circumcision for MSM: evidence for action. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(4):e388–9.

Yuan T, et al. Circumcision to prevent HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global data. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(4):e436–47.

Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014 ( https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/128048/9789241507431_eng.pdf;jsessionid=9E28F952562641C8A01D54C0AC1517E5?sequence=1 accessed 28 December 2021).

Muzyka CN, et al. A Kenyan newspaper analysis of the limitations of voluntary medical male circumcision and the importance of sustained condom use. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:465.

Serwadda DM, Kigozi G. Does medical male circumcision result in sexual risk compensation in Africa? Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(7):e883–4.

Kaufman MR, et al. Voluntary medical male circumcision among adolescents: a missed opportunity for HIV behavioral interventions. Aids. 2017;31 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S233-s241.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China Excellent Young Scientists Fund (82022064); Natural Science Foundation of China International/Regional Research Collaboration Project (72061137001); Natural Science Foundation of China Young Scientist Fund (81703278); the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (2018ZX10721102); the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (SZSM201811071); the High Level Project of Medicine in Longhua, Shenzhen (HLPM201907020105); the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFC0840900); the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission Basic Research Program (JCYJ20190807155409373); Special Support Plan for High-Level Talents of Guangdong Province (2019TQ05Y230); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (58000–31620005); and Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

All funding parties did not have any role in the design of the study or in the explanation of the data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision: Progress and Challenges

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Y., Sun, Y., Zheng, W. et al. Risk Compensation in Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision Programs. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 19, 516–521 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-022-00635-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-022-00635-9