Abstract

Purpose of review

This review summarizes technology-based interventions for HIV in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). We highlight potential benefits and challenges to using telehealth in LMICs and propose areas for future study.

Recent findings

We identified several models for using telehealth to expand HIV health care access in LMICs, including telemedicine visits for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and antiretroviral therapy (ART) services, telementoring programs for providers, and virtual peer-support groups. Emerging data support the acceptability and feasibility of these strategies. However, further investigations are needed to determine whether these models are scalable and sustainable in the face of barriers related to cost, infrastructure, and regulatory approval.

Summary

HIV telehealth interventions may be a valuable approach to addressing gaps along the HIV care cascade in LMICs. Future studies should focus on strategies for expanding existing programs to scale and for assessing long-term clinical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite substantial progress in controlling the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic worldwide, several low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) fell behind the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) “90–90-90” targets to diagnose 90% of all HIV-positive individuals, provide antiretroviral therapy (ART) to 90% of those diagnosed, and achieve viral suppression for 90% of those treated by 2020 [1, 2]. New HIV infections have continued to rise in eastern Europe and central Asia, in part due to policy barriers and inadequate attention paid to the needs of historically marginalized populations, including people who inject drugs, transgender people, sex workers, and men who have sex with men [1, 3••]. Access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) remains insufficient in much of western and central Africa and in the Asia and Pacific region. In 2020, the total number of people using PrEP in LMICs reached only 28% of the target of 3 million people, 8% of the new global 2025 target [1].

Telehealth, defined as “the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support and promote long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, health administration, and public health” is a promising tool to overcome persistent obstacles to HIV-related health care in LMICs, including a lack of trained health care professionals, limited infrastructure, and in-person care costs [1, 4]. Telehealth encompasses several domains, including provider-to-patient clinical care, provider-to-provider interactions, electronic consults, and mobile health applications [5•].

In 2020, an estimated 87% of people living in LMICs had access to a mobile phone, and over half of those in LMICs used the Internet [6, 7]. Although telehealth has long been technologically feasible, it was not widely adopted until the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic necessitated remote health care delivery options that supported physical-distancing precautions [8]. After widespread uptake during the pandemic, telehealth has the potential to address existing and growing inequities in the global HIV response by improving both provider-patient and provider-provider communication [9].

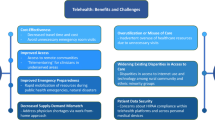

In this review, we summarize the use of telehealth for HIV-related care in LMICs, with a focus on (1) provider-to-provider interventions for clinical training and support, (2) provider-to-patient HIV-related health care delivery via telemedicine, and (3) considerations for overcoming implementation challenges and health system integration in LMICs (Fig. 1). A number of recent reviews have focused on HIV-related telehealth in high-income settings [5•, 10, 11], but experience in LMICs is less well described. We drew from peer-reviewed articles with a focus on data published from 2017 to 2022 to highlight key advances and knowledge gaps in translating telehealth to LMICs for HIV treatment and prevention. In addition, given the limited published experience from LMICs and the rapid pace of implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic, we included models presented at international conferences as well as through direct correspondence with telehealth implementers.

Considerations for HIV telehealth implementation in low- and middle-income countries. The first two panels summarize applications of telehealth for creating demand and for HIV service delivery. The third panel summarizes important considerations related to the scale-up and sustainability of telehealth interventions in low- and middle-income countries

Provider-to-Provider Telehealth for Health Worker Training and Mentoring

The ability to train and retain sufficient human resources for health is a significant barrier to achieving HIV epidemic control in LMICs [12]. HIV is a rapidly evolving field that requires continuing professional development to keep pace with frequently updated local and global recommendations [13••]. Traditional in-person education strategies struggle to overcome challenges related to access, resource limitations, and scalability. Besides the delivery of ART, well-trained health providers are needed to rapidly scale-up PrEP services as well as to manage the rising prevalence of noncommunicable diseases in the aging HIV population in LMICs [14, 15].

Telehealth interventions are increasingly being utilized to provide training, mentoring, and expert consultation on HIV and other diseases in both high-income and LMIC settings. The Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (Project ECHO), pioneered by the University of New Mexico, catalyzed the scale-up of telehealth training for professional development and improving patient outcomes in the USA [16,17,18]. The model uses telehealth technology to connect community-based physicians with specialists from academic medical centers for training and patient co-management [16]. ECHO-like models have been developed for training health professionals on a variety of chronic diseases including HIV [5•, 18,19,20].

Adaptations of ECHO and other tele-training and mentoring programs for HIV health worker capacity building have been implemented in many LMICs including Vietnam [13••], Philippines [personal communication, Leyritana], Namibia [21••], and others across Asia, Africa, and Latin America [22, 23]. In Vietnam, an HIV telehealth capacity-building program was developed and scaled to more than 15 public health institutions over a 4-year period. The program included virtual certificate training courses, webinars for continuing education, and telementoring including case-based discussions, patient co-management and expert consultation, and communication to support public health program implementation [13••]. In Namibia, the Ministry of Health and Social Services piloted an HIV clinical educational curriculum consisting of didactic and case-based discussions delivered via weekly 90-min sessions over Zoom™ videoconferencing technology. Regional clinical mentors served as on-site facilitators to encourage participation and information sharing across sites. Following the pilot, the program was expanded to serve doctors, nurses, and pharmacists at over 50 hospitals and health care centers across Namibia [21••].

In addition to videoconferencing-based training and mentoring, a variety of mobile health (mHealth) and learning (mLearning) programs have been developed to support health care workers providing HIV prevention and care in LMICs. While discussion of these applications is beyond the scope of this review, a recent review of mHealth interventions in LMIC settings found that most data are limited to small pilot programs [24]. One notable innovation has been the use of WhatsApp or other messaging applications to facilitate a community of practice among HIV providers [22, 24, 25].

Evaluations of HIV telementoring programs have reported increased provider knowledge, self-efficacy, motivation, satisfaction, and reduced perception of isolation [13••, 21••]. Most participants reported appreciating the accessibility of the telementoring platforms and expressed their desire to continue participating in future sessions. However, with a few exceptions in high-income countries [18, 26], limited data exists on the impact of telementoring programs on patient outcomes [27].

Telemedicine for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (Tele-PrEP)

Differentiated models of PrEP service delivery such as key population (KP)-led PrEP services, mobile health clinics and pharmacy-led PrEP aim to ensure that PrEP is accessible to all who could benefit including KPs and other vulnerable groups [28, 29]. Telehealth and mHealth approaches to generating demand and delivering PrEP are increasingly being implemented and tested to support these efforts and show promise in overcoming barriers to PrEP uptake [5•]. A recent systematic review concluded that virtual service delivery models for PrEP were effective and feasible to implement [30•].

While much of the published experience to date comes from high-resource settings, Tele-PrEP programs in LMICs are accelerating [31]. A review of PrEP service delivery in 21 PEPFAR countries identified multiple adaptations made by country programs to maintain PrEP services during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to multi-month dispensing of PrEP and decentralization of PrEP delivery, identified best practices included the use of social media to engage communities and create demand, and telehealth service delivery such as organizing PrEP initiation and adherence counseling over the phone or sending prescriptions via WhatsApp [32•, 33]. We highlight several notable examples of Tele-PrEP implementation in LMICs.

In Brazil, telehealth strategies were developed and implemented to maintain HIV PrEP services among adults and adolescents during COVID-19-related health system disruptions [34••, 35]. At one large PrEP clinic in Rio de Janeiro, telemedicine procedures included initial HIV rapid testing and telephone consultation followed by the provision of a digital prescription for a 120-day PrEP supply plus two HIV self-test kits. Follow-up teleconsultations were performed remotely by telephone call, with results of HIV self-tests sent using a digital picture. A cross-sectional web-based survey of PrEP users demonstrated high acceptability with PrEP teleconsultation and home delivery [36].

In Vietnam, the Ministry of Health recently launched a national Tele-PrEP pilot program with the participation of 20 clinical sites in seven provinces [37]. According to the Vietnam Tele-PrEP guidelines, an initial in-person consultation is required for clinical examination, baseline laboratory test, and PrEP prescription. If the client is enrolled in Tele-PrEP, follow-up visits are conducted via telephone or video-conferencing consultation with a remote prescription for PrEP medications which can be purchased at the pharmacy or, if part of a free PrEP program, can be picked up at the clinic or delivered to the client’s home. HIV testing is recommended before each PrEP follow-up visit and must be conducted at a certified laboratory or via a home-based laboratory service.

In Thailand, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the roll-out of tele-PrEP within existing KP-led PrEP health services (KPLHS) [31]. The KPLHS provides health services identified and designed by KPs and delivered by trained and qualified lay providers [38]. PrEP is prescribed remotely by doctors and dispensed by KP lay providers. In the Thai model, the PrEP initiation and initial follow-up visits remained in-person. For those on PrEP for more than 3 months, virtual visits were offered along with self-sampling and self-testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. A second fully online PrEP delivery model in Thailand provided comprehensive HIV services through telehealth including ART and PrEP services. For PrEP, if an individual had a negative HIV test within 7 days of the appointment, a creatinine within 6 months and an HBsAg test within 1 year, they could see a physician via videoconferencing, make an on-line payment, and receive PrEP medications shipped to their home [31].

In Kenya, telehealth services were integrated into the HIV prevention and PrEP programs for adolescent girls and young women to ensure continuity of services during the pandemic. Outreach and counseling through “virtual safe spaces” (via telephone, text messages, WhatsApp) combined with home delivery of PrEP medications, HIV self-test kits, sanitary packs, and condoms enabled continuity of prevention services [39]. Of note, PrEP home delivery was an option only for those who did not need HIV testing (required every 3 months) since HIV testing was provided at health facilities.

Telemedicine for HIV Care and Treatment

For people living with HIV (PLHIV) in resource-limited settings, the high frequency of clinic appointments required in traditional HIV service delivery models presents a barrier to ART scale-up and maintenance [28, 40]. Person-centered differentiated service delivery (DSD) models including multi-month dispensing of ART, community-based medication pickup points, out-of-facility care, and task shifting to KP lay providers [41,42,43], aim to improve treatment access and reduce unnecessary burdens on the health system [44].

Consistent with WHO recommendations beginning in 2016 [45], HIV programs around the world have reduced the standard visit frequency from monthly to every 3 or 6 months. The implementation of extended appointment intervals increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, as it became a practical necessity to promote physical distancing, particularly within health facilities to avoid bringing together patients with co-morbidities who were at increased risk of severe illness. Many clinics in higher income countries have adopted telehealth interventions as part of their DSD models to reach and screen patients, provide counseling, offer follow-up services, and promote retention in care via both telephone and video-conference consultations [42, 46].

However, implementation of telehealth-assisted ART interventions to date has been limited in LMICs. In 2017, Thailand’s Institute of HIV Research and Innovation (IHRI) piloted the same-day antiretroviral therapy (SDART) initiation program at the Thai Red Cross Anonymous Clinic (TRCAC) [47••]. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the SDART program became the first known ART initiation model to integrate telehealth into its services.

SDART was divided into three parts: ART preparation, ART initiation, and post-initiation follow-up. After receiving a positive HIV test result, clients received post-test counseling, were assessed for willingness to start SDART, and were started on therapy if eligible. After SDART initiation, clients were scheduled for a 2-week follow-up visit either virtually or in-person, during which they received baseline laboratory results, physical examination, and ART side effect assessment and management. Telehealth follow-up visits were conducted via LINE, a popular mobile application in Thailand with free audio and video calls. Individuals who had limited access to high-speed Internet used audio-only calls and sent photographs of laboratory test reports or visible symptoms via LINE chat. ART refill was provided via mail delivery. In 2021, an estimated 35% of the clinic’s patients utilized telehealth services for SDART follow-up visits. Providers and patients who engaged in virtual visits reported increased service access, saved time and cost, improved confidentiality, and reduced stigma.

In April 2020, the Helios Salud clinic in Buenos Aires, Argentina, similarly became one of the first health institutions in a LMIC to implement telemedicine for ART-related services to minimize the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV care [48••]. Health-insured patients could meet virtually with their physicians via WhatsApp, which was linked to their electronic medical records. Pharmacies offered home delivery services for ART prescriptions bimonthly. In 2020, 32% of the clinic’s medical visits were conducted virtually with a median patient satisfaction of 5/5 on post-visit surveys. Additionally, ART coverage, pharmacy withdrawals, and virologic suppression all remained over 90% and were comparable to the clinic’s outcomes in the years before the pandemic.

While these examples are encouraging, longer term data are needed to evaluate the impact of telemedicine programs on access, adherence, and retention to care for PLHIV in resource-limited settings [42, 49, 50].

Telehealth Interventions for Psychosocial Support

Globally, PLHIV experience higher rates of mental health disorders than the general population [51, 52]. In turn, impairment in mental health leads to negative health outcomes at each step in the HIV care continuum, from the initial diagnosis to viral suppression [53,54,55,56]. Evidence from LMICs demonstrates that interventions integrating peer support are among the most effective in improving individuals’ ability to engage with HIV care [57, 58]. However, the limited availability of mental health resources and providers in LMICs presents a barrier to their scale-up.

Technology-based approaches such as videoconferencing, voice-calling, text messaging, social media support groups, and Internet-based programs show promise in improving access to psychosocial interventions for PLHIV. To date, most research on digital mental health interventions among PLHIV remains focused on high-income country settings [59]. However, a number of programs were established in LMICs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Kenya, a mobile counseling and peer support intervention for mental health and ART adherence was established for adolescents living with HIV (ALHIV) [60••]. Thirty ALHIV receiving care at the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH)-Turbo clinic in western Kenya were provided with a smartphone and assigned to a WhatsApp group facilitated by a trained counselor. Participants were encouraged to talk informally with other peers in the WhatsApp groups, who could also communicate one-on-one via direct messaging, voice messaging, and video calls. The counselor contacted participants via direct messaging every other week for individual check-ins, and participants were allowed to contact the counselor individually as needed. Following the 6-month intervention, participants reported that the intervention helped them improve their ART adherence by establishing a peer support network. Additionally, participants developed their ability to identify and articulate their experiences with stigma, non-adherence, and mental health challenges.

In Zambia, adolescent pregnant women living with HIV were recruited from Antenatal Clinics to participate in Project Insaka, a mobile phone-based intervention to address the mental health impact of social isolation and stigma [61••]. Sixty-one participants received a smartphone on which they used the Rocket.Chat application to anonymously communicate via text message in small groups led by a trained peer facilitator. Health professionals including a gynecologist, nutritionist, and primary care physician were invited to run virtual workshops throughout the program to increase health literacy. After the 4-month intervention participants self-reported an increase in social support and a reduction in internalized stigma.

In Nigeria, Social Media to promote Adherence and Retention in Treatment (SMART) Connections was established as a social media-based support group for ALHIV [62••]. Participants on ART for less than 12 months were recruited from 14 health facilities in south-central Nigeria and randomly assigned to either the SMART Connection intervention or a control group in which they continued to receive standard clinical care for HIV treatment. Study participants received a smartphone, and those in the intervention group (n = 177) were placed in private Facebook groups led by trained facilitators living with HIV. Participants engaged in daily activities, including interactive polls, live discussions, social chats, and educational activities. After 22 weeks, participants reported high levels of satisfaction and that they preferred online support groups, either alone or in combination with an in-person group, rather than in-person groups only. While the probability of retention in care and ART adherence was similar between the intervention and control groups, participants who completed the intervention had significantly higher HIV-related knowledge and reported feeling a greater sense of unity and belonging.

Challenges to Telehealth in LMICs

While telehealth holds promise for the prevention and management of HIV and other chronic diseases in LMICs, there are several challenges to consider before widespread implementation can be realized [63, 64]. At the national level, countries may lack sufficient legal and regulatory frameworks to guide telemedicine implementation [65]. Regulations such as those governing licensure, online prescribing, and financial reimbursement mechanisms may need to be developed or modified [66]. A 2015 WHO evaluation found that only 22% of the 125 countries surveyed had a national policy for telehealth [67]. A lack of national strategy for telehealth can lead to gaps in coordination among stakeholders, particularly between the private and public sectors. Many pilot programs in LMICs have been funded by private donors and run without the involvement of local governments [24, 68].

At the implementation level, issues of privacy, confidentiality, and data security are of paramount importance for patients, particularly for PLHIV and KPs seeking HIV-related care [3••, 69]. Telemedicine can pose greater privacy risks than in-person visits. Housemates or family members may be nearby or may interrupt telehealth conversations, cell phones or computers could inadvertently reveal patient information to others, and home-based lab kits or medication delivery could inadvertently disclose patient health information. Health care providers should select telemedicine technology platforms with appropriate safeguards and data security. Workflows may need to be restructured to facilitate virtual delivery of health services and health care providers need training on how to best deliver patient care and HIV services via telehealth [65].

While telehealth interventions may improve access to care in some populations, there is a risk of exacerbating disparities for already vulnerable groups, including those without access to digital devices, inexperienced technology users, individuals with limited literacy, and people with disabilities [3••]. A study in rural Uganda identified gender disparity in electronic possessions as one of the biggest challenges in adapting mHealth technology [70]. Therefore, HIV telemedicine programs should be designed with an understanding of the needs and characteristics of the target population, including their access to technology and their health and digital literacy [11, 71].

Laboratory services pose another important challenge to telemedicine in LMICs. Small-scale HIV self-testing interventions increased linkage to HIV care in the Philippines [72], Thailand [73], and Vietnam [74]. However, few programs had the capacity to also prescribe treatment, resulting in low rates of PrEP and ART initiation. Community-led programs with integrated testing and treatment services, such as that in Vietnam and in one Philippines-based health center, saw higher ART initiation rates [72, 74]. Creating a fully virtual telemedicine experience requires the integration of all required laboratory testing, including screening for sexually transmitted infections, into the virtual care model. Approaches include accessing testing services at laboratory sites near patients’ homes, phlebotomy home visits for specimen collection, and home specimen self-collection with shipping to central laboratories for analysis [75••]. Of those approaches, the use of self-collection kits holds the most promise for advancing HIV telemedicine models [76]. Small studies, conducted in the USA, have demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of home specimen self-collection kits for laboratory testing as part of Tele-PrEP programs [75••, 77]. However, similar studies in LMICs are lacking and recognized challenges, including cost, regulatory approval, quality assurance, and the potential for exacerbating disparities in health care access, may be magnified in LMIC settings [76].

Additionally, many health systems in LMICs lack centralized electronic health record systems for efficient health information management and sharing across telehealth programs and platforms (e.g., from clinics to pharmacies) [78]. In Mexico, health professionals from four Tele-PrEP implementation sites reported that some patients had trouble acquiring medicines using prescriptions received electronically [79]. Furthermore, the human resource constraints in many LMICs may limit programs’ ability to effectively train health workers to use new technologies without being an additional burden on health care systems and personnel [13••, 63, 80, 81].

Implementation of telehealth training and mentoring programs is less complex compared to telemedicine. However, the expansion and sustainability of such programs also face barriers related to cost, human resources, infrastructure, and Internet connectivity [13••, 82].

Conclusion

Worldwide, the need to reduce face-to-face consultations while maintaining the quality and accessibility of health care services has fueled the expansion of telehealth, particularly in the era of COVID-19. While there has been considerable attention to the advantages of telehealth in high-income countries, the implementation of technology-assisted services for HIV-related care may have an even greater benefit in circumventing infrastructure limitations, a scarcity of health care providers, and high in-person care costs in LMICs. However, much of the available evidence on the effects of telehealth in LMICs are still anecdotal and/or are derived from pilot studies and small-scale implementation. Nonetheless, many examples demonstrate significant potential in expanding health care access to vulnerable populations and promoting progress towards the UNAIDS 90–90-90 targets.

Interventions currently being implemented and evaluated in the context of HIV include health care delivery via videoconferencing, voice, and texting modalities; telementoring platforms (e.g., Project ECHO); and smartphone-application-based peer-support groups. The studies identified in this review provide evidence for the suitability and efficacy of such tools for maintaining essential health services in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, decreasing stigma, reducing socioeconomic disparities in health care access, and strengthening primary health care delivery. Telehealth in HIV care additionally provides a unique opportunity to improve patient-provider trust, connection, and communication, thereby promoting more patient-centered care and increasing patient preference for utilizing virtual services.

Future research should evaluate telehealth interventions in LMICs implemented to scale, evaluating their outcomes across different populations—particularly in rural and under-resourced settings where Internet connectivity remains limited, a key limitation among many of the articles reviewed. Additional funding options and increased advocacy for regulations that better support telehealth interventions are yet needed to extend their reach. Furthermore, additional research is required for tailored telehealth innovations for KPs.

There is also a continued need for interventions to incorporate demand creation using web-based and social media platforms for educational messaging and anti-stigma campaigns [3••]. Community leaders can also be engaged in promoting sexual health education, PrEP awareness, and peer support networks. Furthermore, machine learning can be used to identify individuals who might benefit from HIV-related care. Wearable devices can additionally be employed to provide reminders to improve adherence to daily medications or to provide location information for testing and pharmacy services.

Given the rapid pace of advancements in both digital technologies and HIV treatment strategies, we anticipate substantial changes in telehealth modalities, provider training, and virtual care coverage in the upcoming years to meet the needs of PLHIV. Even after the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine has the potential to offer more equitable, accessible, and differentiated care to vulnerable populations in LMICs as we work toward ending the HIV epidemic.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

UNAIDS. 2021 UNAIDS Global AIDS update — confronting inequalities — lessons for pandemic responses from 40 years of AIDS [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Aug 9]. Available from:https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2021/2021-global-aids-update.

UNAIDS. Fast-track - ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2022 Aug 9]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/JC2686_WAD2014report.

•• UNAIDS, WHO. Innovate, implement, integrate: virtual interventions in response to HIV, sexually transmitted infections and viral hepatitis [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 9]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2022/policy-brief_virtual-interventions. A policy brief providing guidance for programs and governments to develop, adapt, and implement virtual HIV interventions that are tailored to the context and needs of priority populations.

Office for the Advancement of Telehealth | HRSA [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jun 20]. Available from: https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/topics/telehealth.

• Touger R, Wood BR. A review of telehealth innovations for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019;16:113–9. A review of telehealth interventions for PrEP dissemination and adherence, including provider-to-patient, provider-to-provider, and e-consult modalities.

The World Bank. Individuals using the Internet (% of population) - low & middle income | Data [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jun 21]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=XO.

Mobile cellular subscriptions - low & middle income | Data [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jun 21]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.CEL.SETS?locations=XO.

World Health Organization. Implementing telemedicine services during COVID-19: guiding principles and considerations for a stepwise approach. 2021 [cited 2022 May 2]; Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1346306/retrieve.

World Health Organization, International Telecommunication Union. WHO guideline: recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening [Internet]. Be healthy, be mobile: a handbook on how to implement mSafeListening. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 [cited 2022 Jun 21]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/352284.

Budak JZ, Scott JD, Dhanireddy S, Wood BR. The impact of COVID-19 on HIV care provided via telemedicine—past, present, and future. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2021;18:98–104.

Smith E, Badowski ME. Telemedicine for HIV care: current status and future prospects. HIV Dove Press. 2021;13:651–6.

Bärnighausen T, Bloom DE, Humair S. Human resources for treating HIV/AIDS: are the preventive effects of antiretroviral treatment a game changer? PLOS One. Public Library of Science; 2016;11:e0163960.

•• Pollack TM, Nhung VTT, Vinh DTN, Hao DT, Trang LTT, Duc PA, et al. Building HIV healthcare worker capacity through telehealth in Vietnam. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5: e002166. Evaluation and lessons learned from the development and scale up of an HIV telehealth training and mentoring program in Vietnam.

Were DK, Musau A, Atkins K, Shrestha P, Reed J, Curran K, et al. Health system adaptations and considerations to facilitate optimal oral pre-exposure prophylaxis scale-up in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet HIV. 2021;8:e511–20.

Autenrieth CS, Beck EJ, Stelzle D, Mallouris C, Mahy M, Ghys P. Global and regional trends of people living with HIV aged 50 and over: estimates and projections for 2000–2020. PLoS ONE. 2018;13: e0207005.

Arora S, Kalishman S, Thornton K, Dion D, Murata G, Deming P, et al. Expanding access to hepatitis C virus treatment–Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) project: disruptive innovation in specialty care. Hepatology. 2010;52:1124–33.

Arora S, Kalishman SG, Thornton KA, Komaromy MS, Katzman JG, Struminger BB, et al. Project ECHO: a telementoring network model for continuing professional development. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2017;37:239–44.

Wood BR, Bauer K, Lechtenberg R, Buskin SE, Bush L, Capizzi J, et al. Direct and indirect effects of a project ECHO longitudinal clinical tele-mentoring program on viral suppression for persons with HIV: a population-based analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2022;90:538–45.

Wood BR, Mann MS, Martinez-Paz N, Unruh KT, Annese M, Spach DH, et al. Project ECHO: telementoring to educate and support prescribing of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by community medical providers. Sex Health. 2018;15:601–5.

Wood BR, Unruh KT, Martinez-Paz N, Annese M, Ramers CB, Harrington RD, et al. Impact of a telehealth program that delivers remote consultation and longitudinal mentorship to community HIV providers. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3:ofw123.

Bikinesi L, O’Bryan G, Roscoe C, Mekonen T, Shoopala N, Mengistu AT, et al. Implementation and evaluation of a Project ECHO telementoring program for the Namibian HIV workforce. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18:61. A mixed-methods evaluation of the pilot Project ECHO HIV telementoring program in Namibia demonstrating improved healthcare worker knowledge and satisfaction and decreased professional isolation.

Talisuna AO, Bonkoungou B, Mosha FS, Struminger BB, Lehmer J, Arora S, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: broad partnerships for the rapid scale up of innovative virtual approaches for capacity building and credible information dissemination in Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:255.

The University of New Mexico. ECHO Global Health Initiatives in HIV, TB, Health Security | ECHO Initiative [Internet]. [cited 2022 Aug 13]. Available from: https://hsc.unm.edu/echo/partner-portal/echos-initiatives/global.html.

Gimbel S, Kawakyu N, Dau H, Unger JA. A missing link: HIV-/AIDS-related mHealth interventions for health workers in low- and middle-income countries. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15:414–22.

Bertman V, Petracca F, Makunike-Chikwinya B, Jonga A, Dupwa B, Jenami N, et al. Health worker text messaging for blended learning, peer support, and mentoring in pediatric and adolescent HIV/AIDS care: a case study in Zimbabwe. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17:41.

Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, Deming P, Kalishman S, Dion D, et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2199–207.

McBain RK, Sousa JL, Rose AJ, Baxi SM, Faherty LJ, Taplin C, et al. Impact of project ECHO models of medical tele-education: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:2842–57.

Rousseau E, Julies RF, Madubela N, Kassim S. Novel platforms for biomedical HIV prevention delivery to key populations — community mobile clinics, peer-supported, pharmacy-led PrEP delivery, and the use of telemedicine. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2021;18:500–7.

Green K, Baggaley R, Ngure K, Rosenberg Z, Van Der Merwe LLA, Poonkasetwattana M, et al. Where does PrEP need to go? Considerations to ensure new PrEP products meet the needs and reach those who need it. [Internet]. Virtual; 2021 [cited 2022 Aug 9]. Available from: https://theprogramme.ias2021.org/Programme/Session/221.

• Patel P, Kerzner M, Reed JB, Sullivan PS, El-Sadr WM. Public health implications of adapting HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis programs for virtual service delivery in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: systematic review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022;8: e37479. A systematic review of virtual service delivery models for PrEP. The authors suggest a comprehensive virtual service delivery model for PrEP including the use of the internet and social media for demand creation, HIV community or self-testing, telehealth platforms for risk assessment and follow-up, and mhealth applications for adherence and appointment reminders.

Ramautarsing, Reshmie. Let’s take going virtual viral - moving services online in Thailand [Internet]. Virtual; 2021 [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://theprogramme.ias2021.org/People/PeopleDetailStandalone/160.

• Kerzner M, De AK, Yee R, Keating R, Djomand G, Stash S, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake and service delivery adaptations during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in 21 PEPFAR-funded countries. Krakower DS, editor. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0266280. An analysis of PrEP uptake in PEPFAR programs before and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 21 PEPFAR-funded countries, including an analysis of descriptive program narratives demonstrating the importance of service delivery adaptations in the maintenance and scale up of PrEP.

PEPFAR, Department of State. PEPFAR Technical Guidance in Context of COVID-19 pandemic. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/01.19.2022-PEPFAR-Technical-Guidance-During-COVID.pdf. Accessed 5 July 2022.

•• Hoagland B, Torres TS, Bezerra DRB, Geraldo K, Pimenta C, Veloso VG, et al. Telemedicine as a tool for PrEP delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic in a large HIV prevention service in Rio de Janeiro-Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2020;24:360–4. A description of a PrEP telemedicine approach implemented in Rio de Janeiro during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil.

Dourado I, Magno L, Soares F, Massa P, Nunn A, Dalal S, et al. Adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic: continuing HIV prevention services for adolescents through telemonitoring. Brazil AIDS Behav. 2020;24:1994–9.

Hoagland B, Torres TS, Bezerra DRB, Benedetti M, Pimenta C, Veloso VG, et al. High acceptability of PrEP teleconsultation and HIV self-testing among PrEP users during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2020;101037.

Vietnam Ministry of Health. Decision number 792/QĐ-BYT. Plan for pilot implementation of HIV pre-exposure via telemedicine (Tele-PrEP). Hanoi; 2022.

Vannakit R, Andreeva V, Mills S, Cassell MM, Jones MA, Murphy E, et al. Fast-tracking the end of HIV in the Asia Pacific region: domestic funding of key population-led and civil society organisations. Lancet HIV. 2020;7:e366–72.

Daniel, Oluoch-Madiang’. Viability of sustaining access to and uptake of HIV and sexual and reproductive health services for adolescent girls and young women through virtual interventions in Kenya: the PATH experience. [Internet]. Virtual; 2021 [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2021/06/29/default-calendar/virtual-interventions-global-innovations-and-approaches-across-the-hiv-cascade-for-key-populations.

Roy M, Bolton Moore C, Sikazwe I, Holmes CB. A review of differentiated service delivery for HIV treatment: effectiveness, mechanisms, targeting, and scale. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019;16:324–34.

Grimsrud A, Wilkinson L. Acceleration of differentiated service delivery for HIV treatment in sub-Saharan Africa during COVID-19. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24: e25704.

Rogers BG, Coats CS, Adams E, Murphy M, Stewart C, Arnold T, et al. Development of telemedicine infrastructure at an LGBTQ+ clinic to support HIV prevention and care in response to COVID-19, Providence. RI AIDS Behav. 2020;24:2743–7.

Jongbloed K, Parmar S, van der Kop M, Spittal PM, Lester RT. Recent evidence for emerging digital technologies to support global HIV engagement in care. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12:451–61.

Ehrenkranz P, Grimsrud A, Holmes CB, Preko P, Rabkin M. Expanding the vision for differentiated service delivery: a call for more inclusive and truly patient-centered care for people living with HIV. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2021;86:147–52.

World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach [Internet]. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 [cited 2022 Aug 10]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/208825.

Lyons N, Francis WS, Edwards J, Lavia O. Telehealth combined with differentiated ART delivery improves ART pick up during COVID-19 at a large HIV treatment facility in Trinidad and Tobago. World J AIDS. Scientific Research Publishing; 2021;11:50–9.

•• Amatavete S, Lujintanon S, Teeratakulpisarn N, Thitipatarakorn S, Seekaew P, Hanaree C, et al. Evaluation of the integration of telehealth into the same-day antiretroviral therapy initiation service in Bangkok, Thailand in response to COVID-19: a mixed-method analysis of real-world data. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(Suppl 6): e25816. A study describing the use of telehealth for ART follow-up consultations with ART delivery for patients at the TRCAC clinic in Bangkok, Thailand.

•• Rodriguez-Iantorno, Paula. Successful implementation of telemedicine and pharmacy enhanced HIV services as response to COVID-19 quarantine among health insured patients in Argentina [Internet]. Virtual; 2021. Available from: https://theprogramme.ias2021.org/Abstract/Abstract/1384. Accessed 3 July 2022. A presentation on as-of-yet unpublished data about the use of telemedicine visits and home delivery services for ART at the Helios Salud clinic in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Mgbako O, Miller EH, Santoro AF, Remien RH, Shalev N, Olender S, et al. COVID-19, telemedicine, and patient empowerment in HIV care and research. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:1990–3.

Dandachi D, Freytag J, Giordano TP, Dang BN. It is time to include telehealth in our measure of patient retention in HIV care. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:2463–5.

O’Cleirigh C, Magidson JF, Skeer MR, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Prevalence of psychiatric and substance abuse symptomatology among HIV-infected gay and bisexual men in HIV primary care. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:470–8.

Gaynes BN, Pence BW, Eron JJ, Miller WC. Prevalence and comorbidity of psychiatric diagnoses based on reference standard in an HIV+ patient population. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:505–11.

Leserman J. Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:539–45.

Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:181–7.

Krumme AA, Kaigamba F, Binagwaho A, Murray MB, Rich ML, Franke MF. Depression, adherence and attrition from care in HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2015;69:284–9.

Uthman OA, Magidson JF, Safren SA, Nachega JB. Depression and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low-, middle- and high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11:291–307.

van Luenen S, Garnefski N, Spinhoven P, Spaan P, Dusseldorp E, Kraaij V. The benefits of psychosocial interventions for mental health in people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:9–42.

Sikkema KJ, Dennis AC, Watt MH, Choi KW, Yemeke TT, Joska JA. Improving mental health among people living with HIV: a review of intervention trials in low- and middle-income countries. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2015;2: e19.

Kempf M-C, Huang C-H, Savage R, Safren SA. Technology-delivered mental health interventions for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA): a review of recent advances. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12:472–80.

•• Chory A, Callen G, Nyandiko W, Njoroge T, Ashimosi C, Aluoch J, et al. A Pilot study of a mobile intervention to support mental health and adherence among adolescents living with HIV in Western Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2022;26:232–42. A prospective study evaluating the acceptability and feasibility of the WhatsApp platform to provide individual counseling and peer support for ALHIV in western Kenya.

•• Simpson N, Kydd A, Phiri M, Mbewe M, Sigande L, Gachie T, et al. Insaka: mobile phone support groups for adolescent pregnant women living with HIV. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:663. A study describing a mobile phone-based peer support intervention for adolescent pregnant women living with HIV, moderated by trained peer mentors, in Zambia.

•• Dulli L, Ridgeway K, Packer C, Murray KR, Mumuni T, Plourde KF, et al. A social media–based support group for youth living with HIV in Nigeria (SMART Connections): randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22: e18343. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the acceptability and outcomes of a social media-based peer support intervention for ALHIV in Nigeria.

Hoffer-Hawlik MA, Moran AE, Burka D, Kaur P, Cai J, Frieden TR, et al. Leveraging telemedicine for chronic disease management in low- and middle-income countries during COVID-19. Glob Heart. 15:63.

Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare SAGE Publications. 2018;24:4–12.

Tran BX, Hoang MT, Vo LH, Le HT, Nguyen TH, Vu GT, et al. Telemedicine in the COVID-19 pandemic: motivations for integrated, interconnected, and community-based health delivery in resource-scarce settings? Front Psychiatry. 2020;11: 564452.

Shachar C, Engel J, Elwyn G. Implications for telehealth in a postpandemic future: regulatory and privacy issues. JAMA. 2020;323:2375–6.

WHO. Global diffusion of eHealth: making universal health coverage achievable: report of the third global survey on eHealth [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2022 Sep 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241511780.

Long L-A, Pariyo G, Kallander K. Digital Technologies for health workforce development in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2018;6:S41–8.

Smith MK, Xu RH, Hunt SL, Wei C, Tucker JD, Tang W, et al. Combating HIV stigma in low- and middle-income healthcare settings: a scoping review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23: e25553.

Chang LW, Kagaayi J, Arem H, Nakigozi G, Ssempijja V, Serwadda D, et al. Impact of a mHealth intervention for peer health workers on AIDS care in rural Uganda: a mixed methods evaluation of a cluster-randomized trial. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1776–84.

Rodriguez JA, Clark CR, Bates DW. Digital health equity as a necessity in the 21st century cures act era. JAMA. 2020;323:2381–2.

Eustaquio PC, Figuracion R, Izumi K, Morin MJ, Samaco K, Flores SM, et al. Outcomes of a community-led online-based HIV self-testing demonstration among cisgender men who have sex with men and transgender women in the Philippines during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:366.

Phanuphak N, Jantarapakde J, Himmad L, Sungsing T, Meksena R, Phomthong S, et al. Linkages to HIV confirmatory testing and antiretroviral therapy after online, supervised, HIV self-testing among Thai men who have sex with men and transgender women. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23: e25448.

Green KE, Vu BN, Phan HT, Tran MH, Ngo HV, Vo SH, et al. From conventional to disruptive: upturning the HIV testing status quo among men who have sex with men in Vietnam. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21: e25127.

•• Chasco EE, Hoth AB, Cho H, Shafer C, Siegler AJ, Ohl ME. Mixed-methods evaluation of the incorporation of home specimen self-collection kits for laboratory testing in a telehealth program for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:2463–82. A mixed methods evaluation of home specimen self-collection kits for laboratory monitoring as part of the Iowa TelePrEP program in the USA. Clients were given the choice of using a home kit or visiting a laboratory site for routine monitoring.

Kersh EN, Shukla M, Raphael BH, Habel M, Park I. At-home specimen self-collection and self-testing for sexually transmitted infection screening demand accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic: a review of laboratory implementation issues. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59:e02646-e2720.

Siegler AJ, Mayer KH, Liu AY, Patel RR, Ahlschlager LM, Kraft CS, et al. Developing and assessing the feasibility of a home-based preexposure prophylaxis monitoring and support program. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:501–4.

Akhlaq A, McKinstry B, Muhammad KB, Sheikh A. Barriers and facilitators to health information exchange in low- and middle-income country settings: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31:1310–25.

Cruz-Bañares A, Rojas-Carmona A, Martínez-Dávalos A, Aguilera-Mijares S, Bautista-Arredondo S, Vermandere H. PrEP and telemedicine in times of COVID-19: experiences of health professionals in Mexico [Internet]. Virtual; 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 8]. Available from: https://programme.aids2022.org/Abstract/Abstract/?abstractid=9903.

Feroz A, Jabeen R, Saleem S. Using mobile phones to improve community health workers performance in low-and-middle-income countries. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:49.

Banda N, Muyombwe N, Siangonya B, Daka J, Myunda N, Moonga A, et al. Integrating mental health care into primary HIV care treatment programs in Zambia using telemedicine: challenges and opportunities [Internet]. Virtual; 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 8]. Available from: https://programme.aids2022.org/Abstract/Abstract/?abstractid=11489.

Valenzuela JI, Arguello A, Cendales JG, Rizo CA. Web-based asynchronous teleconsulting for consumers in Colombia: a case study. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9: e33.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

TMP and LAC report grants from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the United States Administration for International Development. JMP was supported by award numbers T32GM007753 and T32GM144273 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the National Institutes of Health, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the United States Administration for International Development. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on eHealth and HIV

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Phan, J.M., Kim, S., Linh, Đ.T.T. et al. Telehealth Interventions for HIV in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 19, 600–609 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-022-00630-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-022-00630-0