Abstract

Many data associate low protease inhibitor plasma concentrations with suboptimal virologic responses, whereas fewer data associate high plasma concentrations with toxicity. Knowledge of relationships between concentrations and virologic response is important because significant variability in concentrations exists among patients. For antiretroviralnaïve patients, target trough concentrations have been suggested on the basis of retrospective associations with virologic responses. Two prospective studies demonstrated improved virologic responses when indinavir and nelfinavir doses were managed based on these troughs. Investigations among antiretroviral-experienced patients have identified a relationship between the trough concentration and the in-vitro susceptibility of the patient’s virus with virologic outcome. However, differences in virologic response may further depend on other pharmacologic factors, such as protein binding, intracellular kinetics, function of drug transporters, and the activity of other drugs in the regimen. In the future, dosing strategies that accommodate the variability in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics may improve virologic outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

Report of the NIH panel to define principles of therapy of HIV infection and guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep 1998, 47:1–41. A source of information for protease inhibitor pharmacokinetics, including drug-drug and drug-food interactions and dosing information. The document was last updated November 2003. It is accessible at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov.

Drusano GL, Bilello JA, Stein DS, et al.: Factors influencing the emergence of resistance to indinavir: role of virologic, immunologic, and pharmacologic variables. J Infect Dis 1998, 178:360–367.

Moore RD, Chaisson RE: Natural history of HIV infection in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 1999, 13:1933–1942.

Wit FW, van Leeuwen R, Weverling GJ, et al.: Outcome and predictors of failure of highly active antiretroviral therapy: one-year follow-up of a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected persons. J Infect Dis 1999, 179:790–798.

Paredes R, Mocroft A, Kirk O, et al.: Predictors of virological success and ensuing failure in HIV-positive patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy in Europe: results from the EuroSIDA study. Arch Intern Med 2000, 160:1123–1132.

Powderly WG, Saag MS, Chapman S, et al.: Predictors of optimal virological response to potent antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 1999, 13:1873–1880.

Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al.: Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med 2000, 133:21–30.

Fischl M, Rodriguez A, Scerpella E, et al.: Impact of directly observed therapy on outcomes in HIV clinical trials. Paper presented at the 7th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. San Francisco, CA; January 30-February 4, 2000.

Fletcher CV: Pharmacologic considerations for therapeutic success with antiretroviral agents. Ann Pharmacother 1999, 33:989–995.

Kaletra. Chicago, IL: Abbott Laboratories; 2000.

Acosta EP, Kakuda TN, Brundage RC, et al.: Pharmacodynamics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors. Clin Infect Dis 2000, 30:S151-S159.

Bristol-Myers Squibb Company: BMS-232632: atazanavir briefing document May 2003. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/ dockets/ac/03/briefing/3950B1_01_bristolmyerssquibbatazanavir. pdf. Accessed July 17, 2003.

Flexner C: Dual protease inhibitor therapy in HIV-infected patients: pharmacologic rationale and clinical benefits. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2000, 40:649–674. This paper is an in-depth review of dual or pharmacokinetically enhanced protease inhibitor combinations.

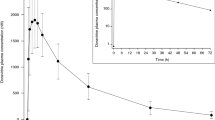

Gieschke R, Fotteler B, Buss N, Steimer JL: Relationships between exposure to saquinavir monotherapy and antiviral response in HIV-positive patients. Clin Pharmacokinet 1999, 37:75–86. This paper contains an excellent graphic demonstration of the wide degree of interpatient variability in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics among a large group of protease inhibitor-naïve subjects.

Cohen Stuart JW, Schuurman R, Burger DM, et al.: Randomized trial comparing saquinavir soft gelatin capsules versus indinavir as part of triple therapy (CHEESE study). AIDS 1999, 13:F53-F58.

Weverling GL, Lange J, Jurriaans S, et al.: Alternative multidrug regimen provides improved suppression of HIV-1 replication over triple therapy. AIDS 1998, 12:F117-F122.

Kirk O, Katzenstein TL, Gerstoft J, et al.: Combination therapy containing ritonavir plus saquinavir has superior short-term antiretroviral efficacy: a randomized trial. AIDS 1999, 13:F9-F16.

Walmsley S, Bernstein B, King M, et al.: Lopinavir-ritonavir versus nelfinavir for the initial treatment of HIV infection. N Engl J Med 2002, 346:2039–2046.

Burger DM, Hoetelmans RM, Hugen PW, et al.: Low plasma concentrations of indinavir are related to virological treatment failure in HIV-1-infected patients on indinavir containing triple therapy. Antiviral Ther 1998, 3:215–220.

Burger DM, Hugen PW, Aarnoutse RE, et al.: Treatment failure of nelfinavir-containing triple therapy can largely be explained by low nelfinavir plasma concentrations. Ther Drug Monit 2003, 25:73–80.

Acosta EP, Henry K, Baken L, et al.: Indinavir concentrations and antiviral effect. Pharmacotherapy 1999, 19:708–712.

Descamps D, Flandre P, Calvez V, et al.: Mechanisms of virologic failure in previously untreated HIV-infected patients from a trial of induction-maintenance therapy. JAMA 2000, 283:205–211.

Hoetelmans R, Reijers M, Weverling GJ, et al.: The effect of plasma drug concentrations on HIV-1 clearance rate during quadruple drug therapy. AIDS 1998, 12:F111-F115.

Mueller BU, Zeichner SL, Kuznetsov VA, et al.: Individual prognoses of long-term responses to antiretroviral treatment based on virological, immunological and pharmacological parameters measured during the first week under therapy. AIDS 1998, 12:F191–196.

Stein DS, Fish DG, Bilello JA, et al.: A 24-week open-label phase I/II evaluation of the HIV protease inhibitor MK-639 (indinavir). AIDS 1996, 10:485–492.

Harris M, Durakovic C, Rae S, et al.: A pilot study of nevirapine, indinavir, and lamivudine among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus disease who have had failure of combination nucleoside therapy. J Infect Dis 1998, 177:1514–1520.

Lorenzi P, Yerly S, Abderrakim K, et al.: Toxicity, efficacy, plasma drug concentrations and protease mutations in patients with advanced HIV infection treated with ritonavir plus saquinavir. Swiss HIV Cohort Study. AIDS 1997, 11:F95-F99.

Durant J, Clevenbergh P, Garraffo R, et al.: Importance of protease inhibitor plasma levels in HIV-infected patients treated with genotypic-guided therapy: pharmacological data from the Viradapt Study. AIDS 2000, 14:1333–1339. This paper demonstrated that the optimal virologic response to therapy was dependent on therapeutic guidance from resistance information and the presence of higher protease inhibitor plasma concentrations. Genotype-guided therapy alone or high drug concentrations alone were less optimal.

Fletcher CV, Brundage RC, Remmel RP, et al.: Pharmacologic characteristics of indinavir, didanosine, and stavudine in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children receiving combination therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000, 44:1029–1034.

Sadler BM, Gillotin C, Lou Y, Stein DS: Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor amprenavir after multiple oral dosing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001, 45:30–37. A good example of protease inhibitor concentration-effect relationships and the wide degree of interpatient variability in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

Schapiro JM, Winters MA, Stewart F, et al.: The effect of highdose saquinavir on viral load and CD4+ T-cell counts in HIV-infected patients. Ann Intern Med 1996, 124:1039–1050.

Vanhove GF, Gries JM, Verotta D, et al.: Exposure-response relationships for saquinavir, zidovudine, and zalcitabine in combination therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1997, 41:2433–2438.

Molla A, Korneyeva M, Gao Q, et al.: Ordered accumulation of mutations in HIV protease confers resistance to ritonavir. Nat Med 1996, 7:760–766.

Fletcher CV, Acosta EP, Cheng H, et al.: Competing drug-drug interactions among multidrug antiretroviral regimens used in the treatment of HIV-infected subjects: ACTG 884. AIDS 2000, 14:2495–2501.

Burger D, Boyd M, Duncombe C, et al.: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of indinavir with or without low-dose ritonavir in HIV-infected Thai patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 2003, 51:1231–1238.

Gatti G, Di Biagio A, Casazza R, et al.: The relationship between ritonavir plasma levels and side effects: implications for therapeutic drug monitoring. AIDS 1999, 13:2083–2089.

Gutierrez F, Padilla S, Navarro A, et al.: Lopinavir plasma concentrations and changes in lipid levels during salvage therapy with lopinavir/ritonavir-containing regimens. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003, 33:594–600.

Anderson PL, Brundage RC, Kakuda TN, Fletcher CV: CD4 response is correlated with peak plasma concentrations of indinavir in adults with undetectable human immunodeficiency virus ribonucleic acid. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2002, 71:280–285.

Haas DW, Arathoon E, Thompson MA, et al.: Comparative studies of two-times-daily versus three-times-daily indinavir in combination with zidovudine and lamivudine. AIDS 2000, 14:1973–1978.

Danner SA, Carr A, Leonard JM, et al.: A short-term study of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of ritonavir, an inhibitor of HIV-1 protease. European-Australian Collaborative Ritonavir Study Group. N Engl J Med 1995, 333:1528–1533.

Back D, Gatti G, Fletcher CV, et al.: Therapeutic drug monitoring in HIV infection: current status and future directions. AIDS 2002, 16(Suppl 1):S5–37. This is a comprehensive review of important considerations for and the current state of therapeutic drug monitoring for HIV infection.

Kakuda TN, Page LM, Anderson PL, et al.: Pharmacological basis for concentration-controlled therapy with zidovudine, lamivudine, and indinavir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001, 45:236–242.

Fletcher CV, Anderson PL, Kakuda TN, et al.: Concentrationcontrolled compared with conventional antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection. AIDS 2002, 16:551–560. This paper describes a prospective randomized study evaluating dosing interventions to meet plasma drug targets versus fixed doses of indinavir, lamivudine, and zidovudine.

Burger D, Hugen P, Reiss P, et al.: Therapeutic drug monitoring of nelfinavir and indinavir in treatment-naive HIV-1-infected individuals. AIDS 2003, 17:1157–1165. This paper describes a prospective randomized study evaluating adherence and dosing interventions to meet plasma drug targets for indinavir, indinavir/ritonavir, and nelfinavir versus standard of care.

Larder B, Harrigan P: Establishment of biologically relevant cut-offs for HIV drug-resistance testing. AIDS 2000, 14(Suppl 4):S111.

Harrigan PR, Hertogs K, Verbiest W, et al.: Baseline HIV drug resistance profile predicts response to ritonavir-saquinavir protease inhibitor therapy in a community setting. AIDS 1999, 13:1863–1871.

Shulman N, Zolopa A, Havlir D, et al.: Virtual inhibitory quotient predicts response to ritonavir boosting of indinavirbased therapy in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with ongoing viremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002, 46:3907–3916. This paper describes a demonstration of virologic response after increasing indinavir plasma concentrations in patients with indinavirresistant virus.

Hsu A, Isaacson J, Brun S, et al.: Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analysis of lopinavir-ritonavir in combination with efavirenz and two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in extensively pretreated human immunodeficiency virusinfected patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003, 47:350–359.

Boffito M, Arnaudo I, Raiteri R, et al.: Clinical use of lopinavir/ ritonavir in a salvage therapy setting: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. AIDS 2002, 16:2081–2083.

Clevenbergh P, Garraffo R, Durant J, Dellamonica P: Pharm-Adapt: a randomized prospective study to evaluate the benefit of therapeutic monitoring of protease inhibitors: 12 week results. AIDS 2002, 16:2311–2315.

Hill A, Craig C, Whittaker L: Prediction of drug potency Cmin/ IC50 ratio: false precision? AIDS 2000, 14(Suppl 4):S90.

Molla A, Vasavanonda S, Kumar G, et al.: Human serum attenuates the activity of protease inhibitors toward wild-type and mutant human immunodeficiency virus. Virology 1998, 250:255–262.

Fellay J, Marzolini C, Meaden ER, et al.: Response to antiretroviral treatment in HIV-1-infected individuals with allelic variants of the multidrug resistance transporter 1: a pharmacogenetics study. Lancet 2002, 359:30–36. The first description of the relationship between P-glycoprotein genotypes, immunologic responses, and protease inhibitor plasma concentrations. However, these findings have been difficult for other studies to replicate.

Nascimbeni M, Lamotte C, Peytavin G, et al.: Kinetics of antiviral activity and intracellular pharmacokinetics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors in tissue culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999, 43:2629–2634.

Snyder S, D’Argenio DZ, Weislow O, et al.: The triple combination indinavir-zidovudine-lamivudine is highly synergistic. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000, 44:1051–1058.

Lee CG, Ramachandra M, Jeang KT, et al.: Effect of ABC transporters on HIV-1 infection: inhibition of virus production by the MDR1 transporter. FASEB J 2000, 14:516–522.

Fletcher CV, Anderson PL, Kakuda TN, et al.: A novel approach to integrate pharmacologic and virologic characteristics: an in vivo potency (IVP) index for antiretroviral agents. Paper presented at the 8th Conference of Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Chicago, IL; February 4–8, 2001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anderson, P.L., Fletcher, C.V. Updated clinical pharmacologic considerations for HIV-1 protease inhibitors. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 1, 33–39 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-004-0005-z

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-004-0005-z