Abstract

Purpose of Review

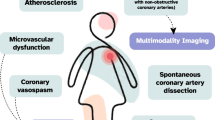

The prevalence of CVD in women is increasing and is due to the increased prevalence of CV risk factors. Traditional CV risk assessment tools for prevention have failed to accurately determine CVD risk in women. CAC has shown to more precisely determine CV risk and is a better predictor of CV outcomes. Coronary CTA provides an opportunity to determine the presence of CAD and initiate prevention in women presenting with angina. Identifying women with INOCA due to CMD with use of cPET or cMRI with MBFR is vital in managing these patients. This review article outlines the role of imaging in preventive cardiology for women and will include the latest evidence supporting the use of these imaging tests for this purpose.

Recent Findings

CV mortality is higher in women who have more extensive CAC burden. Women have a greater prevalence of INOCA which is associated with higher MACE. INOCA is due to CMD in most cases which is associated with traditional CVD risk factors. Over half of these women are untreated or undertreated. Recent study showed that stratified medical therapy, tailored to the specific INOCA endotype, is feasible and improves angina in women.

Summary

Coronary CTA is useful in the setting of women presenting with acute chest pain to identify CAD and initiate preventive therapy. CAC confers greater relative risk for CV mortality in women versus (vs.) men. cMRI or cPET is useful to assess MBFR to diagnose CMD and is another useful imaging tool in women for CV prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

16 January 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-023-01838-1

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Tsao CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2022 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;145(8):e153–639.

Wilmot KA, et al. Coronary heart disease mortality declines in the United States from 1979 through 2011: evidence for stagnation in young adults, especially women. Circulation. 2015;132(11):997–1002.

Arora S, et al. Twenty year trends and sex differences in young adults hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2019;139(8):1047–56.

Gulati M, et al. Adverse cardiovascular outcomes in women with nonobstructive coronary artery disease: a report from the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation Study and the St James Women Take Heart Project. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(9):843–50.

Wenger N. Tailoring cardiovascular risk assessment and prevention for women: one size does not fit all. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2017;2017(1):e201701.

Agarwala A, et al. The use of sex-specific factors in the assessment of women’s cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2020;141(7):592–9.

Park KE, Pepine CJ. Assessing cardiovascular risk in women: looking beyond traditional risk factors. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25(2):152–3.

Greenland P, et al. Coronary calcium score and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(4):434–47.

Bots ML, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness and coronary atherosclerosis: weak or strong relations? Eur Heart J. 2007;28(4):398–406.

Finn AV, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. Correlation between carotid intimal/medial thickness and atherosclerosis: a point of view from pathology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(2):177–81.

Bairey Merz CN, et al. Ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA): developing evidence-based therapies and research agenda for the next decade. Circulation. 2017;135(11):1075–92.

Reynolds HR, et al. Coronary arterial function and disease in women with no obstructive coronary arteries. Circ Res. 2022;130(4):529–51.

• Bradley C, Berry C. Definition and epidemiology of coronary microvascular disease. J Nucl Cardiol. 2022;29(4):1763–75. A comprehensive review of the definition, epidemiology, and diagnosis of coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD).

Murthy VL, et al. Clinical quantification of myocardial blood flow using PET: joint position paper of the SNMMI Cardiovascular Council and the ASNC. J Nucl Med. 2018;59(2):273–93.

Engblom H, et al. Fully quantitative cardiovascular magnetic resonance myocardial perfusion ready for clinical use: a comparison between cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2017;19(1):78.

Hsu LY, et al. Diagnostic performance of fully automated pixel-wise quantitative myocardial perfusion imaging by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(5):697–707.

Knott KD, et al. Quantitative myocardial perfusion in coronary artery disease: a perfusion mapping study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;50(3):756–62.

Ford TJ, et al. Stratified medical therapy using invasive coronary function testing in angina: the CorMicA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(23 Pt A):2841–55.

Garcia M, et al. Cardiovascular disease in women. Circ Res. 2016;118(8):1273–93.

DeFilippis EM, et al. Women who experience a myocardial infarction at a young age have worse outcomes compared with men: the Mass General Brigham YOUNG-MI registry. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(42):4127–37.

Okunrintemi V, et al. Gender differences in patient‐reported outcomes among adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(24):e010498.

Hemal K, et al. Sex differences in demographics, risk factors and presentation in stable contemporary outpatients with suspected coronary artery disease: insights from the promise trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13_Supplement):2095–2095.

Khoudary SRE, et al. Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: implications for timing of early prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(25):e506–32.

Campbell DJ, et al. Differences in myocardial structure and coronary microvasculature between men and women with coronary artery disease. Hypertension. 2011;57(2):186–92.

Samargandy S, et al. Arterial stiffness accelerates within 1 year of the final menstrual period: the SWAN heart study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(4):1001–8.

Nair GV, et al. Pulse pressure and coronary atherosclerosis progression in postmenopausal women. Hypertension. 2005;45(1):53–7.

Kenkre TS, et al. Ten-year mortality in the WISE study (women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(12):e003863.

Arnett DK, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596–646.

Aggarwal NR, et al. Sex differences in ischemic heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(2):e004437.

Smolina K, et al. Sex disparities in post-acute myocardial infarction pharmacologic treatment initiation and adherence. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(6):586–92.

Khan SU, et al. A comparative analysis of premature heart disease- and cancer-related mortality in women in the USA, 1999–2018. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2022;8(3):315–23.

Curtin SC. Trends in cancer and heart disease death rates among adults aged 45–64: United States, 1999–2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(5):1–9.

Samayoa L, et al. Sex differences in cardiac rehabilitation enrollment: a meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(7):793–800.

Grundtvig M, et al. Sex-based differences in premature first myocardial infarction caused by smoking: twice as many years lost by women as by men. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16(2):174–9.

Peters SA, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as risk factor for incident coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts including 858,507 individuals and 28,203 coronary events. Diabetologia. 2014;57(8):1542–51.

Elder P, et al. Identification of female-specific risk enhancers throughout the lifespan of women to improve cardiovascular disease prevention. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2020;2:100028.

O’Kelly AC, et al. Pregnancy and reproductive risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women. Circ Res. 2022;130(4):652–72.

Hauspurg A, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and future maternal cardiovascular disease. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41(2):239–46.

Avina-Zubieta JA, et al. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(12):1690–7.

Giannelou M, Mavragani CP. Cardiovascular disease in systemic lupus erythematosus: A comprehensive update. J Autoimmun. 2017;82:1–12.

Goff DC Jr, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S49-73.

Ridker PM, et al. Development and validation of improved algorithms for the assessment of global cardiovascular risk in women: the Reynolds Risk Score. JAMA. 2007;297(6):611–9.

JBS3 Board. Joint British Societies' consensus recommendations for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (JBS3). Heart. 2014;100(Suppl 2):ii1–ii67. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305693. PMID: 24667225

Livingstone S, Morales DR, Donnan PT, Payne K, Thompson AJ, Youn JH, Guthrie B. Effect of competing mortality risks on predictive performance of the QRISK3 cardiovascular risk prediction tool in older people and those with comorbidity: external validation population cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2(6):e352–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00088-X. Erratum in: Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021 Aug;2(8):e458. PMID: 34100008; PMCID: PMC8175241.

Singh A, et al. Cardiovascular risk and statin eligibility of young adults after an MI: partners YOUNG-MI registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(3):292–302.

Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Use of risk assessment tools to guide decision-making in the primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a special report from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. Circulation. 2019;139(25):e1162–77.

DeFilippis AP, et al. An analysis of calibration and discrimination among multiple cardiovascular risk scores in a modern multiethnic cohort. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):266–75.

Cooney MT, et al. Cardiovascular risk estimation in older persons: SCORE O.P. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(10):1093–103.

Michos ED, Blaha MJ, Blumenthal RS. Use of the coronary artery calcium score in discussion of initiation of statin therapy in primary prevention. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(12):1831–41.

Blaha MJ, et al. Role of coronary artery calcium score of zero and other negative risk markers for cardiovascular disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation. 2016;133(9):849–58.

• Dzaye O, et al. Coronary artery calcium scores indicating secondary prevention level risk: findings from the CAC consortium and FOURIER trial. Atherosclerosis. 2022;347:70–6. A retrospective analysis from the CAC consortium and FOURIER trial that found that primary prevention individuals with increased CAC burden may have annualized ASCVD mortality rates equivalent to persons with stable secondary prevention level risk. These findings argue for a risk continuum between higher risk primary prevention and stable secondary prevention patients, as their ASCVD risks may overlap.

Orringer CE, et al. The National Lipid Association scientific statement on coronary artery calcium scoring to guide preventive strategies for ASCVD risk reduction. J Clin Lipidol. 2021;15(1):33–60.

Cainzos-Achirica M, et al. Coronary artery calcium for personalized allocation of aspirin in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in 2019: the MESA study (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). Circulation. 2020;141(19):1541–53.

Miedema MD, et al. Use of coronary artery calcium testing to guide aspirin utilization for primary prevention: estimates from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(3):453–60.

McClelland RL, et al. Distribution of coronary artery calcium by race, gender, and age: results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation. 2006;113(1):30–7.

Lessmann N, et al. Sex differences in coronary artery and thoracic aorta calcification and their association with cardiovascular mortality in heavy smokers. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(9):1808–17.

Budoff MJ, et al. Ten-year association of coronary artery calcium with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(25):2401–8.

Raggi P, et al. Gender-based differences in the prognostic value of coronary calcification. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2004;13(3):273–83.

Shaw LJ, et al. Sex differences in calcified plaque and long-term cardiovascular mortality: observations from the CAC Consortium. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(41):3727–35.

Mehta A, et al. Predictive value of coronary artery calcium score categories for coronary events versus strokes: impact of sex and race: MESA and DHS. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(8):e010153.

Lakoski SG, et al. Coronary artery calcium scores and risk for cardiovascular events in women classified as “low risk” based on Framingham risk score: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(22):2437–42.

Kelkar AA, et al. Long-term prognosis after coronary artery calcium scoring among low-intermediate risk women and men. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(4):e003742.

Bellasi A, et al. Comparison of prognostic usefulness of coronary artery calcium in men versus women (results from a meta- and pooled analysis estimating all-cause mortality and coronary heart disease death or myocardial infarction). Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(3):409–14.

Nakanishi R, et al. All-cause mortality by age and gender based on coronary artery calcium scores. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17(11):1305–14.

Wong ND, et al. Sex differences in coronary artery calcium and mortality from coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and all causes in adults with diabetes: the coronary calcium consortium. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(10):2597–606.

Gulati M, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021;144(22):e368–454.

Pagidipati NJ, et al. Sex differences in functional and CT angiography testing in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(22):2607–16.

Investigators S-H, et al. Coronary CT angiography and 5-year risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(10):924–33.

Pepine CJ, et al. Emergence of nonobstructive coronary artery disease: a woman’s problem and need for change in definition on angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(17):1918–33.

Pagidipati NJ, et al. Sex differences in long-term outcomes of patients across the spectrum of coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2018;206:51–60.

Leipsic J, et al. Sex-based prognostic implications of nonobstructive coronary artery disease: results from the international multicenter CONFIRM study. Radiology. 2014;273(2):393–400.

Ferencik M, et al. Use of high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaque detection for risk stratification of patients with stable chest pain: a secondary analysis of the PROMISE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(2):144–52.

Gu H, et al. Sex differences in coronary atherosclerosis progression and major adverse cardiac events in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2017;11(5):367–72.

Lee SE, et al. Sex differences in compositional plaque volume progression in patients with coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(11):2386–96.

•• Minhas A, et al. Sex-specific plaque signature: uniqueness of atherosclerosis in women. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2021;23(7):84. A review that outlines the sex differences in the prevalence, progression, and prognostic impact of atherosclerosis in women compared with men. It also reviews the unique differences in atherosclerotic plaque characteristics between men and women on both non-invasive and invasive imaging modalities.

Plichart M, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness in plaque-free site, carotid plaques and coronary heart disease risk prediction in older adults. The Three-City Study. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219(2):917–24.

Mehta A, et al. Association of carotid artery plaque with cardiovascular events and incident coronary artery calcium in individuals with absent coronary calcification: the MESA. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(4):e011701.

Willeit P, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness progression as surrogate marker for cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2020;142(7):621–42.

Tjoe B, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: considerations for diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2021;88(10):561–71.

Reis SE, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is highly prevalent in women with chest pain in the absence of coronary artery disease: results from the NHLBI WISE study. Am Heart J. 2001;141(5):735–41.

Herscovici R, et al. Ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease ( INOCA ): what is the risk? J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(17):e008868.

Taqueti VR. Sex differences in the coronary system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1065:257–78.

Michelsen MM, et al. Women with stable angina pectoris and no obstructive coronary artery disease: closer to a diagnosis. Eur Cardiol. 2017;12(1):14–9.

Taqueti VR, et al. Global coronary flow reserve is associated with adverse cardiovascular events independently of luminal angiographic severity and modifies the effect of early revascularization. Circulation. 2015;131(1):19–27.

Taqueti VR, et al. Excess cardiovascular risk in women relative to men referred for coronary angiography is associated with severely impaired coronary flow reserve, not obstructive disease. Circulation. 2017;135(6):566–77.

Schumann CL, et al. Functional and economic impact of INOCA and influence of coronary microvascular dysfunction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(7):1369–79.

Jespersen L, et al. Symptoms of angina pectoris increase the probability of disability pension and premature exit from the workforce even in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(42):3294–303.

Pepine CJ, et al. Coronary microvascular reactivity to adenosine predicts adverse outcome in women evaluated for suspected ischemia results from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute WISE (Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(25):2825–32.

Mygind ND, et al. Coronary microvascular function and cardiovascular risk factors in women with angina pectoris and no obstructive coronary artery disease: the iPOWER study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(3):e003064.

Ford TJ, et al. Ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease: prevalence and correlates of coronary vasomotion disorders. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(12):e008126.

Ishimori ML, et al. Myocardial ischemia in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(1):27–33.

Recio-Mayoral A, et al. Chronic inflammation and coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients without risk factors for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(15):1837–43.

Weber B, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with psoriasis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2022;29(1):37–42.

Bateman TM, et al. Practical guide for interpreting and reporting cardiac PET measurements of myocardial blood flow: an information statement from the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, and the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. J Nucl Med. 2021;62(11):1599–615.

Taqueti VR, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and future risk of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(10):840–9.

Giubbini R, et al. Comparison between N(13)NH(3)-PET and (99m)Tc-Tetrofosmin-CZT SPECT in the evaluation of absolute myocardial blood flow and flow reserve. J Nucl Cardiol. 2021;28(5):1906–18.

Knott KD, et al. The prognostic significance of quantitative myocardial perfusion: an artificial intelligence-based approach using perfusion mapping. Circulation. 2020;141(16):1282–91.

Greenland P, et al. Primary prevention trial designs using coronary imaging: a national heart, lung, and blood institute workshop. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(7):1454–65.

Muhlestein JB, et al. Coronary artery calcium versus pooled cohort equations score for primary prevention guidance: randomized feasibility trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(5):843–55.

Denissen SJ, et al. Impact of a cardiovascular disease risk screening result on preventive behaviour in asymptomatic participants of the ROBINSCA trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26(12):1313–22.

Van Der Aalst C, et al. Risk results from screening for a high cardiovascular disease risk by means of traditional risk factor measurement or coronary artery calcium scoring in the ROBINSCA trial. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(Supplement_2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Renée P. Bullock-Palmer reports payment or honoraria from the American College of Cardiology Nuclear Cardiology educational product development and delivery of content and the Knowledge to Practice Webinar on the ACC AHA Chest Pain Guidelines. Renée P. Bullock-Palmer also reports being an American Heart Association – Circulation Imaging Editorial Board Member, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology Board Member, Southern NJ American Heart Association Board Member, and International Accreditation Commission CT Board Member. Erin D. Michos reports consulting fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Esperion, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer. Ron Blankstein reports Amgen Inc. (Steering Committee Member/Research grant), Novartis Inc. (research); consulting fees from Caristo Inc. and Elucid Inc.; payment or honoraria from Siemens Inc.; and Board of Directors, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. Dianna Gaballa has no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cardiac PET, CT, and MRI

The original online version of this article was revised to update Fig. 3 caption.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bullock-Palmer, R.P., Michos, E.D., Gaballa, D. et al. The Role of Imaging in Preventive Cardiology in Women. Curr Cardiol Rep 25, 29–40 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-022-01828-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-022-01828-9