Abstract

Randomized clinical trials have established that lipidlowering pharmacologic therapy can substantially reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with known coronary artery disease (CAD). Researchers are now working to define the role of lipid-lowering agents in the primary prevention of CAD to extend their benefit to patients at increased risk for future coronary events. The risk assessment models presently used for secondary prevention are not sufficient to identify high-risk, asymptomatic patients. Building on the accumulated data about the physiologic mechanisms and metabolic factors that contribute to CAD, novel serum markers and diagnostic tests are being critically studied to gauge their utility for the assessment of high-risk patients and occult vascular disease. New risk prediction models that combine traditional risk factors for CAD with the prudent use of new screening methods will allow clinicians to target proven risk reduction therapies at high-risk patients before they experience a cardiac event.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

American Heart Association: 2000 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update, Dallas: American Heart Association; 2000.

Summary of the second report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel II). JAMA 1993, 269:3015–3023.

American Diabetes Association: Management of dyslipidemia in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 1998, 21:179–182. The ADA advocates treating type 2 diabetics to a LDL goal of less than 100 mg/dL. Several studies have demonstrated that the CHD risk of a middle-aged, asymptomatic, type 2 diabetic is the same as that of a nondiabetic with a history of myocardial infarction.

Frolkis JP, Zyzanski SJ, Schwartz JM, Suhan PS: Physician noncompliance with the 1993 National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP-ATPII) guidelines. Circulation 1998, 98:851–855.

Stafford RS, Blumenthal D, Pasternak RC: Variations in cholesterol management practices of U.S. physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997, 29:139–146.

Allen JK, Blumenthal RS: Coronary risk factors in women six months after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol 1995, 75:1092–1095.

Stone NJ, Nicolosi RJ, Kris-Etherton P, USA: AHA conference proceedings. Summary of the scientific conference on the efficacy of hypocholesterolemic dietary interventions. American Heart Association. Circulation 1996, 94:3388–3391.

Fletcher GF, Balady G, Blair SN, USA: Statement on exercise: benefits and recommendations for physical activity programs for all Americans. A statement for health professionals by the Committee on Exercise and Cardiac Rehabilitation of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Circulation 1996, 94:857–862.

The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial results. I. Reduction in incidence of coronary heart disease. JAMA 1984, 251:351–364.

Frick MH, Elo O, Haapa K, et al.: Helsinki Heart Study: primary-prevention trial with gemfibrozil in middle-aged men with dyslipidemia. Safety of treatment, changes in risk factors, and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 1987, 317:1237–1245.

Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994, 344:1383–1389.

Pfeffer MA, Sacks FM, Moye LA, et al.: Cholesterol and Recurrent Events: a secondary prevention trial for normolipidemic patients. CARE Investigators. Am J Cardiol 1995, 76:98C-106C.

The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group: Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1998, 339:1349–1357.

Influence of pravastatin and plasma lipids on clinical events in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study (WOSCOPS). Circulation 1998, 97:1440–1445.

Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, et al.: Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: Results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study. JAMA 1998, 279:1615–1622. Asymptomatic patients with multiple risk factors (and probably a higher burden of atherosclerotic disease) derive the greatest absolute benefit from statin therapy. The greatest risk reduction with lovastatin was in the subgroup with baseline HDL cholesterol levels less than 40 mg/dL.

Rubins HB, Robins SJ, Collins D, et al.: Gemfibrozil for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in men with low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Intervention Trial Study Group. N Engl J Med 1999, 341:410–418.

Pitt B, Waters D, Brown WV, et al.: Aggressive lipid-lowering therapy compared with angioplasty in stable coronary artery disease. Atorvastatin versus Revascularization Treatment Investigators. N Engl J Med 1999, 341:70–76.

RITA-2 trial participants: Coronary angioplasty versus medical therapy for angina: the second Randomised Intervention Treatment of Angina (RITA-2) trial. Lancet 1997, 350:461–468.

Blumenthal RS, Becker DM, Moy TF, et al.: Exercise thallium tomography predicts future clinically manifest coronary heart disease in a high-risk asymptomatic population. Circulation 1996, 93:915–923.

Smith SC, Jr, Blair SN, Criqui MH, et al.: Preventing heart attack and death in patients with coronary disease. Circulation 1995, 92:2–4.

Grundy SM, Balady GJ, Criqui MH, et al.: Primary prevention of coronary heart disease: guidance from Framingham: a statement for healthcare professionals from the AHA Task Force on Risk Reduction. American Heart. Circulation 1998, 97:1876–1887.

Kannel WB: Range of serum cholesterol values in the population developing coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1995, 76:69C-77C.

Akosah KO, Gower E, Groon L, et al.: Mild hypercholesterolemia and premature heart disease: do the national criteria underestimate disease risk? J Am Coll Cardiol 2000, 35:1178–1184. This recent paper indicates that traditional risk factor screening may miss substantial numbers of patients with significant occult vascular disease. Lifestyle modification should be encouraged to achieve a target LDL cholesterol less than 130 mg/dL and triglycerides lower than 200 mg/dL in all adults.

Smith SC, Jr, Greenland P, Grundy SM: AHA Conference Proceedings. Prevention conference V: beyond secondary prevention: identifying the high-risk patient for primary prevention: executive summary. American Heart Association. Circulation 2000, 101:111–116.

Boushey CJ, Beresford SA, Omenn GS, Motulsky AG: A quantitative assessment of plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease. Probable benefits of increasing folic acid intakes. JAMA 1995, 274:1049–1057.

Mayer EL, Jacobsen DW, Robinson K: Homocysteine and coronary atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996, 27:517–527.

Eikelboom JW, Lonn E, Genest J, Jr, et al.: Homocyst(e)ine and cardiovascular disease: a critical review of the epidemiologic evidence. Ann Intern Med 1999, 131:363–375.

Christen WG, Ajani UA, Glynn RJ, Hennekens CH: Blood levels of homocysteine and increased risks of cardiovascular disease: causal or casual? Arch Intern Med 2000, 160:422–434.

Ridker PM, Manson JE, Buring JE, et al.: Homocysteine and risk of cardiovascular disease among postmenopausal women. JAMA 1999, 281:1817–1821.

Hoogeveen EK, Kostense PJ, Jakobs C, et al.: Hyperhomocysteinemia increases risk of death, especially in type 2 diabetes: 5-year follow-up of the Hoorn Study. Circulation 2000, 101:1506–1511.

Ross R: Atherosclerosis: an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 1999, 340:115–126.

Ridker PM, Rifai N, Pfeffer MA, et al.: Inflammation, pravastatin, and the risk of coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events (CARE) Investigators. Circulation 1998, 98:839–844. Statin therapy was more effective in the subgroup of patients with elevated levels of hs-CRP. Similar testing of CRP levels is now being done from stored samples from the AFCAPS/TexCAPS trial to see if the results are similar with lovastatin in primary prevention.

Kuller LH, Tracy RP, Shaten J, Meilahn EN: Relation of C-reactive protein and coronary heart disease in the MRFIT nested case-control study. Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Am J Epidemiol 1996, 144:537–547.

Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, et al.: Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med 1997, 336:973–979.

Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Rifai N: C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med 2000, 342:836–843.

Scanu AM: Lipoprotein(a). A genetic risk factor for premature coronary heart disease. JAMA 1992, 267:3326–3329.

Sandkamp M, Funke H, Schulte H, et al.: Lipoprotein(a) is an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction at a young age. Clin Chem 1990, 36:20–23.

Rosengren A, Eriksson H, Larsson B, et al.: Secular changes in cardiovascular risk factors over 30 years in Swedish men aged 50: the study of men born in 1913, 1923, 1933 and 1943. J Intern Med 2000, 247:111–118.

Lamarche B, Moorjani S, Lupien PJ, et al.: Apolipoprotein A-I and B levels and the risk of ischemic heart disease during a five-year follow-up of men in the Quebec cardiovascular study. Circulation 1996, 94:273–278.

Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Coleman LD, Pham YM, et al.: Higher prevalence of GPIIIa PlA2 polymorphism in siblings of patients with premature coronary heart disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1999, 123:1223–1229. The platelet polymorphism PlA2 is associated with more avid platelet fibrinogen binding. Aspirin therapy appears to decrease the prothrombic effect associated with the presence of this genetic polymorphism.

Leng GC, Lee AJ, Fowkes FG, et al.: Incidence, natural history and cardiovascular events in symptomatic and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the general population. Int J Epidemiol 1996, 25:1172–1181.

Zheng ZJ, Sharrett AR, Chambless LE, et al.: Associations of ankle-brachial index with clinical coronary heart disease, stroke and preclinical carotid and popliteal atherosclerosis: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Atherosclerosis 1997, 131:115–125.

Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Beasley JW, et al.: ACC/AHA guidelines for exercise testing: executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Exercise Testing). Circulation 1997, 96:345–354.

Bruce RA, DeRouen TA, Hossack KF: Value of maximal exercise tests in risk assessment of primary coronary heart disease events in healthy men. Five years’ experience of the Seattle heart watch study. Am J Cardiol 1980, 46:371–378.

Bruce RA, Hossack KF, DeRouen TA, Hofer V: Enhanced risk assessment for primary coronary heart disease events by maximal exercise testing: 10 years’ experience of Seattle Heart Watch. J Am Coll Cardiol 1983, 2:565–573.

Rautaharju PM, Prineas RJ, Eifler WJ, et al.: Prognostic value of exercise electrocardiogram in men at high risk of future coronary heart disease: Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial experience. J Am Coll Cardiol 1986, 8:1–10.

Burke GL, Evans GW, Riley WA, et al.: Arterial wall thickness is associated with prevalent cardiovascular disease in middleaged adults. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Stroke 1995, 26:386–391.

Chambless LE, Heiss G, Folsom AR, et al.: Association of coronary heart disease incidence with carotid arterial wall thickness and major risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, 1987-1993. Am J Epidemiol 1997, 146:483–494.

O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, et al.: Thickening of the carotid wall. A marker for atherosclerosis in the elderly? Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Stroke 1996, 27:224–231.

Crouse JR, 3rd, Byington RP, Bond MG, et al.: Pravastatin, Lipids, and Atherosclerosis in the Carotid Arteries (PLAC-II). Am J Cardiol 1995, 75:455–459.

Probstfield JL, Margitic SE, Byington RP, et al.: Results of the primary outcome measure and clinical events from the Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Progression Study. Am J Cardiol 1995, 76:47C-53C.

Salonen R, Nyyssonen K, Porkkala E, et al.: Kuopio Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (KAPS). A population-based primary preventive trial of the effect of LDL lowering on atherosclerotic progression in carotid and femoral arteries. Circulation 1995, 92:1758–1764.

Hertzer NR, Young JR, Beven EG, et al.: Coronary angiography in 506 patients with extracranial cerebrovascular disease. Arch Intern Med 1985, 145:849–852.

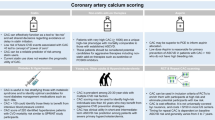

Rumberger JA, Simons DB, Fitzpatrick LA, et al.: Coronary artery calcium area by electron-beam computed tomography and coronary atherosclerotic plaque area. A histopathologic correlative study. Circulation 1995, 92:2157–2162.

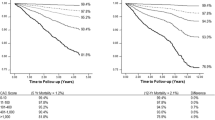

Raggi P, Callister TQ, Cooil B, et al.: Identification of patients at increased risk of first unheralded acute myocardial infarction by electron-beam computed tomography. Circulation 2000, 101:850–855.

Arad Y, Spadaro LA, Goodman K, et al.: Predictive value of electron beam computed tomography of the coronary arteries. 19-month follow-up of 1173 asymptomatic subjects. Circulation 1996, 93:1951–1953.

Detrano RC, Wong ND, Doherty TM, et al.: Coronary calcium does not accurately predict near-term future coronary events in high-risk adults. Circulation 1999, 99:2633–2638.

Rumberger JA, Brundage BH, Rader DJ, Kondos G: Electron beam computed tomographic coronary calcium scanning: A review and guidelines for use in asymptomatic persons. Mayo Clin Proc 1999, 74:243–252.

Caro J, Klittich W, McGuire A, et al.: International economic analysis of primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with pravastatin in WOSCOPS. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Eur Heart J 1999, 20:263–268. The use of pravastatin in asymptomatic, middle-aged men with hyperlipidemia and other traditional risk factors, or in those with nonspecific ST changes on baseline electrocardiogram appears to be quite cost-effective.

Blumenthal RS: Statins: Effective antiatherosclerotic therapy. Am Heart J 2000, 139:577–583.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nass, C.M., Wiviott, S.D., Allen, J.K. et al. Global risk assessment for lipid therapy to prevent coronary heart disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2, 424–432 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-000-0056-8

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-000-0056-8