Abstract

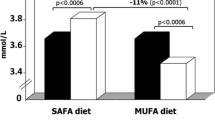

Over the past two decades, cholesterol-lowering drugs have proven to be effective and have been found to significantly reduce the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). However, diet and lifestyle factors are still recognized as the first line of intervention for CHD risk reduction by the National Cholesterol Education Program and the American Heart Association, which now advocate use of viscous fibers and plant sterols, and soy protein and nuts, respectively. In a series of metabolically controlled studies, we have combined these four cholesterol-lowering dietary components in the same diet (ie, a dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods) in an attempt to maximize low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reduction. We have found that the portfolio diet reduced low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by approximately 30% and produced clinically significant reductions in CHD risk. These reductions were the same as found with a starting dose of a first-generation statin drug.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial results. I. Reduction in incidence of coronary heart disease.JAMA 1984, 251:351–364.

The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial results. II. The relationship of reduction in incidence of coronary heart disease to cholesterol lowering.JAMA 1984, 251:365–374.

Downs JR, Clearfield R, Weis S, et al.: Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study. JAMA 1998, 279:1615–1622.

Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group: MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002, 360:7–22.

Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, et al., for the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group: Prevention of coronary disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 1995, 333:1301–1307.

Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, et al.: Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002, 360:1623–1630.

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al.: Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346:393–403.

Jenkins DJ, Popovich DG, Kendall CW, et al.: Effect of a diet high in vegetables, fruit, and nuts on serum lipids. Metabolism 1997, 46:530–537.

Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Popovich DG, et al.: Effect of a very-high-fiber vegetable, fruit, and nut diet on serum lipids and colonic function. Metabolism 2001, 50:494–503.

Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Faulkner D, et al.: A dietary portfolio approach to cholesterol reduction: combined effects of plant sterols, vegetable proteins, and viscous fibers in hypercholesterolemia. Metabolism 2002, 51:1596–1604.

Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Marchie A, et al.: A dietary portfolio of cholesterol lowering foods versus a statin on serum lipids and c-reactive protein. JAMA 2003, 290:502–510.

Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Marchie A, et al.: The effect of combining plant sterols, soy protein, viscous fibers, and almonds in treating hypercholesterolemia. Metabolism 2003, 52:1478–1483.

Kromhout D, Arntzenius AC, van der Velde EA: Diet and coronary heart disease: the Leiden Intervention Trial. Bibl Nutr Dieta 1986, 37:119–120.

Ornish D, Brown SE, Scherwitz LW, et al.: Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? The Lifestyle Heart Trial. Lancet 1990, 336:129–133.

de Lorgeril M, Salen P, Martin JL, et al.: Mediterrean diet, traditional risk factors, and the rate of cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction. Final report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study. Circulation 1999, 99:779–785.

Singh RB, Dubnov G, Niaz MA, et al.: Effect of an Indo-Mediterranean diet on progression of coronary artery disease in high risk patients (Indo-Mediterranean Diet Heart Study): a randomised single-blind trial. Lancet 2002, 360:1455–1461.

Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults: Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001, 285:2486–2497.

Krauss RM, Eckel RH, Howard B, et al.: AHA dietary guidelines revision 2000: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association. Circulation 2000, 102:2284–2299.

United States Food and Drug Administration: Food labeling: health claims; soluble fiber from certain foods and coronary heart disease. [Docket No. 96P-0338]. 1998.

United States Food and Drug Administration: FDA final rule for food labeling: health claims: soy protein and coronary heart disease. Federal Register 64, 57699–57733. September 26, 1999.

United States Food and Drug Administration: FDA authorizes new coronary heart disease health claim for plant sterol and plant stanol esters. Washington, DC: US FDA, Docket Nos. 001-1275, OOP-1276, 2000.

United States Food and Drug Administration: Food labeling: health claims; soluble fiber from whole oats and risk of coronary heart disease. [Docket No. 95P-0197], 15343–15344. 2001.

United States Food and Drug Administration: Food labeling: health claims: nuts & heart Disease. Federal Register. [Docket No. 02P-0505]. 2003.

Fahrenbach MJ, Riccardi BA, Grant WC: Hypocholesterolemic activity of mucilaginous polysaccharides in White Leghorn cockerels. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1966, 123:321–326.

Kritchevsky D: Influence of dietary fiber on bile acid metabolism. Lipids 1978, 13:982–985.

Vahouny GV, Tombes R, Cassidy MM, et al.: Dietary fibers: V. Binding of bile salts, phospholipids and cholesterol from mixed micelles by bile acid sequestrants and dietary fibers. Lipids 1980, 15:1012–1018.

Jenkins DJ, Leeds AR, Gassull MA, et al.: Decrease in postprandial insulin and glucose concentrations by guar and pectin. Ann Intern Med 1977, 86:20–23.

Bourdon I, Yokoyama W, Davis P, et al.: Postprandial lipid, glucose, insulin, and cholecystokinin responses in men fed barley pasta enriched with beta-glucan. Am J Clin Nutr 1999, 69:55–63.

Thacker PA, Solomon MO, Aherne FX, et al.: Influence of propionic acid on the cholesterol metabolism of pigs fed hypercholesterolemic diets. Can J Animal Sci 1981, 61:969–975.

Braaten JT, Wood PJ, Scott FW, et al.: Oat beta-glucan reduces blood cholesterol concentration in hypercholesterolemic subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr 1994, 48:465–474.

Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM, Leeds AR, et al.: Dietary fibres, fibre analogues, and glucose tolerance: importance of viscosity. BMJ 1978, 1:1392–1394.

Sirtori CR, Agradi E, Conti F, et al.: Soybean-protein diet in the treatment of type-II hyperlipoproteinaemia. Lancet 1977, 1:275–277.

Anderson JW, Johnstone BM, Cook-Newell ME: Meta-analysis of the effects of soy protein intake on serum lipids. N Engl J Med 1995, 333:276–282.

Baum JA, Teng H, Erdman JW Jr, et al.: Long-term intake of soy protein improves blood lipid profiles and increases mononuclear cell low-density-lipoprotein receptor messenger RNA in hypercholesterolemic, postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr 1998, 68:545–551.

Crouse JR 3rd, Morgan T, Terry JG, et al.: A randomized trial comparing the effect of casein with that of soy protein containing varying amounts of isoflavones on plasma concentrations of lipids and lipoproteins. Arch Intern Med 1999, 159:2070–2076.

Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Jackson CJ, et al.: Effects of high- and low-isoflavone soyfoods on blood lipids, oxidized LDL, homocysteine, and blood pressure in hyperlipidemic men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 2002, 76:365–372.

Weggemans RM, Trautwein EA: Relation between soy-associated isoflavones and LDL and HDL cholesterol concentrations in humans: a meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003, 57:940–946.

Lovati MR, Manzoni C, Gianazza E, et al.: Soy protein peptides regulate cholesterol homeostasis in Hep G2 cells. J Nutr 2000, 130:2543–2549.

Castiglioni S, Manzoni C, D’Uva A, et al.: Soy proteins reduce progression of a focal lesion and lipoprotein oxidiability in rabbits fed a cholesterol-rich diet. Atherosclerosis 2003, 171:163–170.

Law M: Plant sterol and stanol margarines and health. BMJ 2000, 320:861–864.

Lees AM, Mok HY, Lees RS, et al.: Plant sterols as cholesterol-lowering agents: clinical trials in patients with hypercholesterolemia and studies of sterol balance. Atherosclerosis 1977, 28:325–338.

Jones PJ: Cholesterol-lowering action of plant sterols. Curr Atheroscler Rep 1999, 1:230–235.

Fraser GE, Sabate J, Beeson WL, Strahan TM: A possible protective effect of nut consumption on risk of coronary heart disease. The Adventist Health Study. Arch Intern Med 1992, 152:1416–1424.

Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, et al.: Frequent nut consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women: prospective cohort study. BMJ 1998, 317:1341–1345.

Albert CM, Gaziano JM, Willett WC, Manson JE: Nut consumption and decreased risk of sudden cardiac death in the Physicians’ Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2002, 162:1382–1387.

Kris-Etherton PM, Yu-Poth S, Sabate J, et al.: Nuts and their bioactive individual constituents: effects on serum lipids and other factors that affect disease risk. Am J Clin Nutr 1999, 70(Suppl):504s-511s.

Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Marchie A, et al.: Dose response of almonds on coronary heart disease risk factors: blood lipids, oxidized low-density lipoproteins, lipoprotein(a), homocysteine and pulmonary nitric oxide. A randomized controlled crossover trial. Circulation 2002, 106:1327–1332.

Hyson DA, Schneeman BO, Davis PA: Almonds and almond oil have similar effects on plasma lipids and LDL oxidation in healthy men and women. J Nutr 2002, 132:703–707.

Spiller GA, Miller A, Olivera K, et al.: Effects of plant-based diets high in raw or roasted almonds, or roasted almond butter on serum lipoproteins in humans. J Am Coll Nutr 2003, 22:195–200.

Sabate J, Haddad E, Tanzman JS, et al.: Serum lipid response to the graduated enrichment of a Step I diet with almonds: a randomized feeding trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2003, 77:1379–1384.

Kay R: Diets of early Miocene African hominoids. Nature 1977, 268:628–630.

Milton K: Hunter-gatherer diets—a different perspective. Am J Clin Nutr 2000, 71:665–667.

Teaford MF, Ungar PS: Diet and the evolution of the earliest human ancestors. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2000, 97:13506–11351.

Popovich DG, Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, et al.: Health implications of the Western lowland gorilla diet. J Nutr 1997, 127:2000–2005.

Goodall AG: Feeding and ranging behaviour of a mountain gorilla group (Gorilla gorilla beringei) in the Tshinda-Kahuzi region (Zaire). In Primate Ecology. Edited by Clutton-Brock TH. London: Academic Press; 1977:449–479.

Goodall J. The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1986.

Fossey D. Observations on the home range on one group of mountain gorillas (Gorilla gorilla beringei). Animal Behav 1974, 22:568–581.

Clark AG, Glanowski S, Nielsen R, et al.: Inferring nonneutral evolution from human-chimp-mouse orthologous gene trios. Science 2003, 302:1960–1963.

Eaton SB, Konner MJ: Paleolithic nutrition. A consideration of its nature and current implications. N Engl J Med 1985, 312:283–289.

Cordain L, Miller JB, Eaton SB, Mann N: Macronutrient estimations in hunter-gatherer diets. Am J Clin Nutr 2000, 72:1589–1592.

Cordain L: Cereal grains. Humanity’s double-edged sword. World Rev Nutr Diet 1999, 84:19–73.

Keys A: Mediterranean diet and public health: personal reflections. Am J Clin Nutr 1995, 61(Suppl):321s-332s.

Cleave TL, Campbell GD, Painter NS: Diabetes, Coronary Thrombosis and the Saccharine Disease. Bristol, England: Wright; 1969.

Burkitt DP, Trowell HC: Refined Carbohydrate and Disease. New York: Academic Press; 1975.

Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, et al.: Intake of trans fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease among women. Lancet 1993, 341:581–585.

Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Vuksan V: Viscous fibers, health claims, and strategies to reduce cardiovascular disease risk. Am J Clin Nutr 2000, 71:401–402.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kendall, C.W.C., Jenkins, D.J.A. A Dietary portfolio: Maximal reduction of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol with diet. Curr Atheroscler Rep 6, 492–498 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-004-0091-9

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-004-0091-9