Abstract

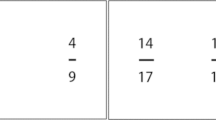

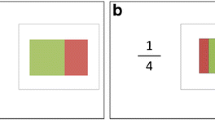

Research suggests that people use a variety of strategies for comparing the numerical values of two fractions. They use holistic strategies that rely on the fraction magnitudes, componential strategies that rely on the fraction numerators or denominators, or a combination of both. We investigated how mathematically skilled adults adapt their strategies to the type of fraction pair. To extend previous research on simple fraction comparison, we used a highly controlled set of more complex fractions with two-digit components. In addition to response times, we recorded eye movements to assess how often the participants fixated on and alternated between specific fraction components. In line with previous studies, our data suggest that the participants preferred componential over holistic strategies for fraction pairs with common numerators or common denominators. Conversely, they preferred holistic over componential strategies for fraction pairs without common components. These results support the assumption that mathematically skilled adults adapt their strategies to the type of fraction pair even in complex fraction comparison. Our study also suggests that eye-tracking is a promising method for measuring strategy use in solving fraction problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that the number of items in the category “no common components” is larger, because this category includes three subcategories, which allowed further analyses of whole number intuitions in fraction processing (the “whole number bias”, see Ni and Zhou 2005). These analyses are, however, not in the focus of this article, so that for the analyses reported here, these subcategories are not analysed separately.

As accuracy rates were extremely high for all categories, we refrained from running significance tests to compare accuracy rates between categories, because such tests would not yield reliable results. Furthermore, systematic analyses of accuracy data is not in the focus of our study.

References

Alibali, M. W., & Sidney, P. G. (2015). Variability in the natural number bias: who, when, how, and why. Learning and Instruction, 37, 56–61. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.01.003.

Bailey, D. H., Hoard, M. K., Nugent, L., & Geary, D. C. (2012). Competence with fractions predicts gains in mathematics achievement. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 113, 447–455. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2012.06.004.

Behr, M. J., Wachsmuth, I., Post, T. R., & Lesh, R. (1984). Order and equivalence of rational numbers: a clinical teaching experiment. Journal of Research in Mathematics Education, 15, 323–341. doi:10.2307/748423.

Behr, M. J., Wachsmuth, I., Post, T. R., & Lesh, R. (1985). Construct a sum: a measure of children’s understanding of fraction size. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 16, 120–131. doi:10.2307/748369.

Bonato, M., Fabbri, S., Umiltà, C., & Zorzi, M. (2007). The mental representation of numerical fractions: real or integer? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 33, 1410–1419. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.33.6.1410.

Booth, J. L., & Newton, K. J. (2012). Fractions: could they really be the gatekeeper’s doorman? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 37, 247–253. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2012.07.001.

Carpenter, T. P., Corbitt, M. K., Kepner, H. S., Lindquist, M. M., & Reys, R. (1981). Results from the second mathematics assessment of the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Washington, DC: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Carraher, D. W. (1996). Learning about fractions. In L. P. Steffe, P. Nesher, P. Cobb, G. A. Goldin, & B. Greer (Eds.), Theories of mathematical learning (pp. 241–266). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Clarke, D. M., & Roche, A. (2009). Students’ fraction comparison strategies as a window into robust understanding and possible pointers for instruction. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 72, 127–138. doi:10.1007/s10649-009-9198-9.

Cramer, K. A., Post, T. R., & delMas, R. C. (2002). Initial fraction learning by fourth- and fifth- grade students: a comparison of the effects of using commercial curricula with the effects of using the rational number project curriculum. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 33, 111–144. doi:10.2307/749646.

Dehaene, S., Piazza, M., Pinel, P., & Cohen, L. (2003). Three parietal circuits for number processing. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 20, 487–506. doi:10.1080/02643290244000239.

DeWolf, M., Grounds, M. A., & Bassok, M. (2014). Magnitude comparison with different types of rational numbers. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 40, 71–82. doi:10.1037/a0032916.

Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1980). Verbal reports as data. Psychological Review, 87, 215–251. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.87.3.215.

Faulkenberry, T. J., & Pierce, B. H. (2011). Mental representations in fraction comparison. Holistic versus component-based strategies. Experimental Psychology, 58, 480–489. doi:10.1027/1618-3169/a000116.

Ganor-Stern, D., Karasik-Rivkin, I., & Tzelgov, J. (2011). Holistic representation of unit fractions. Experimental Psychology, 58, 201–206. doi:10.1027/1618-3169/a000086.

Gómez, D. M., Jiménez, A., Bobadilla, R., Reyes, C., & Dartnell, P. (2015). The effect of inhibitory control on general mathematics achievement and fraction comparison in middle school children. ZDM Mathematics Education,. doi:10.1007/s11858-015-0685-4.

Grant, E. R., & Spivey, M. J. (2003). Eye movements and problem solving: guiding attention guides thought. Psychological Science, 14, 462–466. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.02454.

Green, H. J., Lemaire, P., & Dufau, S. (2007). Eye movement correlates of younger and older adults’ strategies for complex addition. Acta Psychologica, 125, 257–278. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2006.08.001.

Huber, S., Klein, E., Willmes, K., Nuerk, H.-C., & Moeller, K. (2014a). Decimal fraction representations are not distinct from natural number representations—evidence from a combined eye-tracking and computational modeling approach. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 172. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00172.

Huber, S., Moeller, K., & Nuerk, H.-C. (2014b). Adaptive processing of fractions—evidence from eye-tracking. Acta Psychologica, 148, 37–48. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2013.12.010.

Ischebeck, A., Schocke, M., & Delazer, M. (2009). The processing and representation of fractions within the brain. Neuroimage, 47, 403–413. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.041.

Ischebeck, A., Weilharter, M., & Körner, C. (2015). Eye movements reflect and shape strategies in fraction comparison. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/17470218.2015.1046464.

Jacob, S. N., & Nieder, A. (2009a). Notation-independent representation of fractions in the human parietal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29, 4652–4657. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0651-09.2009.

Jacob, S. N., & Nieder, A. (2009b). Tuning to non-symbolic proportions in the human frontoparietal cortex. European Journal of Neuroscience, 30, 1432–1442. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06932.x.

Liang, K. Y., & Zeger, S. L. (1986). Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika, 73, 13–22. doi:10.1093/biomet/73.1.13.

Matthews, P. G., & Chesney, D. L. (2015). Fractions as percepts? Exploring cross-format distance effects for fractional magnitudes. Cognitive Psychology, 78, 28–56. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2015.01.006.

Meert, G., Grégoire, J., & Noël, M.-P. (2009). Rational numbers: componential versus holistic representation of fractions in a magnitude comparison task. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62, 1598–1616. doi:10.1080/17470210802511162.

Meert, G., Grégoire, J., & Noël, M.-P. (2010a). Comparing 5/7 and 2/9: adults can do it by accessing the magnitude of the whole fractions. Acta Psychologica, 135, 284–292. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.07.014.

Meert, G., Grégoire, J., & Noël, M.-P. (2010b). Comparing the magnitude of two fractions with common components: which representations are used by 10- and 12-year-olds? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 107, 244–259. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2010.04.008.

Merkley, R., & Ansari, D. (2010). Using eye tracking to study numerical cognition: the case of the ratio effect. Experimental Brain Research, 206, 455–460. doi:10.1007/s00221-010-2419-8.

Moyer, R. S., & Landauer, T. K. (1967). Time required for judgements of numerical inequality. Nature, 215, 1519–1520. doi:10.1038/2151519a0.

Ni, Y., & Zhou, Y.-D. (2005). Teaching and learning fraction and rational numbers: the origins and implications of whole number bias. Educational Psychologist, 40, 27–52. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep4001_3.

Obersteiner, A., Dresler, T., Reiss, K., Vogel, C. M., Pekrun, R., & Fallgatter, A. J. (2010). Bringing brain imaging to the school to assess arithmetic problem solving. Chances and limitations in combining educational and neuroscientific research. ZDM—The International Journal on Mathematics Education, 42, 541–554. doi:10.1007/s11858-010-0256-7.

Obersteiner, A., Moll, G., Beitlich, J. T., Cui, C., Schmidt, M., Khmelivska, T., & Reiss, K. (2014). Expert mathematicians’ strategies for comparing the numerical values of fractions—evidence from eye movements. In S. Oesterle, C. Nicol, P. Liljedahl, & D. Allan (Eds.), Proceedings of the Joint Meeting of PME 38 and PME-NA 36 (Vol. 4, pp. 338–345). Vancouver: PME.

Obersteiner, A., Van Dooren, W., Van Hoof, J., & Verschaffel, L. (2013). The natural number bias and magnitude representation in fraction comparison by expert mathematicians. Learning and Instruction, 28, 64–72. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.05.003.

Padberg, F. (2009). Didaktik der Bruchrechnung (4th ed.). Heidelberg: Spektrum Akademischer Verlag.

Robinson, K. M. (2001). The validity of verbal reports in children’s subtraction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 211–222. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.93.1.211.

Schneider, M., & Siegler, R. S. (2010). Representations of the magnitudes of fractions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 36, 1227–1238. doi:10.1037/a0018170.

Schneider, M., Heine, A., Thaler, V., Torbeyns, J., De Smedt, B., Verschaffel, L., Jacobs, A. M., & Stern, E. (2008). A validation of eye movements as a measure of elementary school children’s developing number sense. Cognitive Development, 23, 409–422. doi:10.1016/j.cogdev.2008.07.002.

Sekuler, R., & Mierkiewicz, D. (1977). Children’s judgments of numerical inequality. Child Development, 48, 630–633.

Siegler, R. S. (2013). Fractions: the new frontier for theories of numerical development. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17, 13–19. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2012.11.004.

Siegler, R. S., Duncan, G. J., Davis-Kean, P. E., Duckworth, K., Claessens, A., Engel, M., & Chen, M. (2012). Early predictors of high school mathematics achievement. Psychological Science, 23, 691–697. doi:10.1177/0956797612440101.

Siegler, R. S., & Pyke, A. A. (2013). Developmental and individual differences in understanding of fractions. Developmental Psychology, 49, 1994–20014. doi:10.1037/a0031200.

Stafylidou, S., & Vosniadou, S. (2004). The development of students’ understanding of the numerical value of fractions. Learning and Instruction, 14, 503–518. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2004.06.015.

Sullivan, J. L., Juhasz, B. J., Slattery, T. J, & Barth, H. C. (2011). Adults’ number-line estimation strategies: Evidence from eye movements. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 18, 557–563. doi:10.3758/s13423-011-0081-1.

Szücs, D., & Goswami, U. (2007). Educational neuroscience: defining a discipline for the study of mental representations. Mind, Brain, and Education, 1, 114–127. doi:10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00012.x.

Torbeyns, J., Schneider, M., Xin, Z., & Siegler, R. S. (2014). Bridging the gap: fraction understanding is central to mathematics achievement in students from three different continents. Learning and Instruction,. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.03.002.

Tzelgov, J., Ganor-Stern, D., Kallai, A., & Pinhas, M. (2014). Primitives and non-primitives of numerical representations. Oxford Handbooks Online. Retrieved 24 July 2015. http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199642342.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199642342-e-019.

Vamvakoussi, X. (2015). The development of rational number knowledge: old topics, new insights. Learning and Instruction, 37, 50–55. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.01.002.

Vamvakoussi, X., Van Dooren, W., & Verschaffel, L. (2013). Educated adults are still affected by intuitions about the effect of arithmetical operations: evidence from a reaction- time study. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 82, 323–330. doi:10.1007/s10649-012-9432-8.

Vamvakoussi, X., & Vosniadou, S. (2004). Understanding the structure of the set of rational numbers: a conceptual change approach. Learning and Instruction, 14, 453–467. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2004.06.013.

Van Hoof, J., Vandewalle, J., Verschaffel, L., & Van Dooren, W. (2015). In search for the natural number bias in secondary school students’ interpretation of the effect of arithmetical operations. Learning and Instruction, 37, 30–38. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.03.004.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the university students for participating in our study. We also would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Obersteiner, A., Tumpek, C. Measuring fraction comparison strategies with eye-tracking. ZDM Mathematics Education 48, 255–266 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-015-0742-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-015-0742-z