Abstract

Background

Maternal diet is critical to fetal development and lifelong health outcomes. In this context, dietary quality indices in pregnancy should be explicitly underpinned by data correlating food intake patterns with nutrient intakes known to be important for gestation.

Aims

Our aim was to assess the correlation between dietary quality scores derived from a novel online dietary assessment tool (DAT) and nutrient intake data derived from the previously validated Willett Food Frequency Questionnaire (WFFQ).

Methods

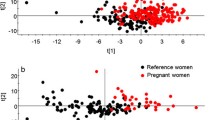

524 women completed the validated semi-quantitive WFFQ and online DAT questionnaire in their first trimester. Spearman correlation and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to test associations between energy-adjusted and energy-unadjusted nutrient intakes derived from the WFFQ, and diet and nutrition scores obtained from the DAT.

Results

Positive correlations were observed between respondents’ diet and nutrition scores derived from the online DAT, and their folate, vitamin B12, iron, calcium, zinc and iodine intakes/MJ of energy consumed derived from the WFFQ (all P < 0.001). Negative correlations were observed between participants’ diet and nutrition scores and their total energy intake (P = 0.02), and their percentage energy from fat, saturated fat, and non-milk extrinsic sugars (NMES) (all P ≤ 0.001). Median dietary fibre, beta carotene, folate, vitamin C and vitamin D intakes derived from the WFFQ, generally increased across quartiles of diet and nutrition score (all P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Scores generated by this web-based DAT correlate with important nutrient intakes in pregnancy, supporting its use in estimating overall dietary quality among obstetric populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Haider BA, Olofin I, Wang M et al (2013) Anaemia, prenatal iron use, and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 346:f3443. doi:10.1136/bmj.f3443

Radlowski EC, Johnson RW (2013) Perinatal iron deficiency and neurocognitive development. Front Hum Neurosci 7:585. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00585

MRC Vitamin Study Research Group (1991) Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. Lancet 338:131–137

Thorne-Lyman A, Fawzi WW (2012) Vitamin D during pregnancy and maternal, neonatal and infant health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 26:75–90. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01283

Mathews F, Yudkin P, Neil A (1999) Influence of maternal nutrition on outcome of pregnancy: prospective cohort study. BMJ 319:339–343

Picciano MF (2003) Pregnancy and lactation: physiological adjustments, nutritional requirements and the role of dietary supplements. J Nutr 133:1997S–2002S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.26811B

Mullaney L, O’Higgins AC, Cawly S et al (2014) An estimation of periconceptional under-reporting of dietary energy intake. J Public Health (Oxf). doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdu086 Epub ahead of print

Illner AK, Freisling H, Boeing H et al (2012) Review and evaluation of innovation technologies for measuring diet in nutritional epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 41:1187–1203. doi:10.1093/ije/dys105

O’Brien OA, McCarthy M, Gibney ER et al (2014) Technology-supported dietary and lifestyle interventions in healthy pregnant women: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Nutr 68:760–766. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2014.59

McGowan CA, Curran S, McAuliffe FM (2014) Relative validity of a food frequency questionnaire to assess nutrient intake in pregnant women. J Hum Nutr Diet 27:167–174. doi:10.1111/jhn.12120

Harrington J (1997) Validation of a food frequency questionnaire as a tool for assessing nutrient intake, MA thesis, health promotion. National University of Ireland, Galway

Kaaks R, Slimani N, Riboli E (1997) Pilot phase studies on the accuracy of dietary intake measurements in the EPIC project: overall evaluation of results. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Epidemiol 26:S26–S36

Morgan K, McGee H, Watson D et al (2008) SLÁN 2007: Survey of lifestyle, attitudes and nutrition in Ireland, main report, Department of Health and Children. The Stationery Office, Dublin

Food Standards Agency (2006) Food portion sizes, 3rd edn. TSO, London

McCance RA, Widdowson EM (2002) McCance and Widdowson’s the composition of foods, 6th edn. Food Standards Agency and Royal Society of Chemistry, Great Britain

Kearney MJ, Kearney JM, Gibney MJ (1997) Methods used to conduct the survey on consumer attitudes to food, nutrition and health on nationally representative samples of adults from each member state of the European Union. Eur J Clin Nutr 51:S3–S7

Kearney JM, Kearney MJ, McElhone S et al (1999) Methods used to conduct the pan-European Union survey on consumer attitudes to physical activity, body weight and health. Public Health Nutr 2:79–86

Allen D, Newsholme HC (2003) Attitudes of Older EU Adults to Diet, Food and Health: a Pan-EU Survey. Campden and Chorleywood Food Research Association Group, UK

European Commission Working Group–Statistics on Income Poverty and Social Exclusion (2003) Laeken indictaors detailed calculation methodology. Luxembourg: Quetelet Room, Bech Building. http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/eusilc/documents/Laeken,Indicators,-calculation,algorithm.pdf. Accessed 08 Jan 2014

Central Statistics Office (2013) EU Survey on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) 2011 and Revised 2010 Results. CSO, Dublin

Food and Agricultural Organisation/World Health Organisation/United Nations University (2001) Human energy requirements. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation. Food and Agricultural Organisation, Rome

Snook-Parrott M, Bodnar LM, Simhan HN et al (2009) Maternal cereal consumption and adequacy of micronutrient intake in the periconceptional period. Public Health Nutr 12:1276–1283. doi:10.1017/S1368980008003881

Grieger JA, Clifton VL (2014) A review of the impact of dietary intakes in human pregnancy on infant birthweight. Nutrients 7:153–178. doi:10.3390/nu7010153

Kuehn D, Aros S, Cassorla F et al (2012) A prospective cohort study of the prevalence of growth, facial, and central nervous system abnormalities in children with heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36:1811–1819. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01794

Murrin C, Shrivastava A, Kelleher CC (2013) Lifeways Cross-generation Cohort Study Steering Group. Maternal macronutrient intake during pregnancy and 5 years postpartum and associations with child weight status aged five. Eur J Clin Nutr 67:670–679. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2013.76

Williams L, Seki Y, Vuguin PM et al (2014) Animal models of in utero exposure to a high fat diet: a review. Biochim Biophys Acta 1842:507–519. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.07.006

White CL, Purpera MN, Morrison CD (2009) Maternal obesity is necessary for programming effect of high-fat diet on offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296:R1464–R1472. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.91015.2008

Hernandez TL, Van Pelt RE, Anderson MA et al (2014) A higher-complex carbohydrate diet in gestational diabetes mellitus achieves glucose targets and lowers postprandial lipids: a randomized crossover study. Diabetes Care 37:1254–1262. doi:10.2337/dc13-2411

Horan MK, McGowan CA, Gibney ER et al (2014) Maternal low glycaemic index diet, fat intake and postprandial glucose influences neonatal adiposity–secondary analysis from the ROLO study. Nutr J 1:13–78. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-13-78

D’Alessandro ME, Oliva ME, Fortino MA et al (2014) Maternal sucrose-rich diet and fetal programming: changes in hepatic lipogenic and oxidative enzymes and glucose homeostasis in adult offspring. Food Funct. 5:446–453. doi:10.1039/c3fo60436e

Englund-Ögge L, Brantsæter AL, Haugen M et al (2012) Association between intake of artificially sweetened and sugar-sweetened beverages and preterm delivery: a large prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 96:552–559. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.031567

Sloboda DM, Li M, Patel R et al (2014) Early life exposure to fructose and offspring phenotype: implications for long term metabolic homeostasis. J Obes 2014:203474. doi:10.1155/2014/203474

Grundt JH, Nakling J, Eide GE et al (2012) Possible relation between maternal consumption of added sugar and sugar-sweetened beverages and birth weight–time trends in a population. BMC Public Health 12:901. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-901

Regnault TR, Gentili S, Sarr O et al (2013) Fructose, pregnancy and later life impacts. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 40:824–837. doi:10.1111/1440-1681.12162

Moses RG, Casey SA, Quinn EG et al (2014) Pregnancy and glycemic index outcomes study: effects of low glycemic index compared with conventional dietary advice on selected pregnancy outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr 99:517–523. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.074138

Saccone G, Berghella V (2015) Omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids to prevent preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 125:663–672. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000668

Saccone G, Berghella V (2015) Omega-3 supplementation to prevent recurrent preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol 213:135–140. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.013

De Giuseppe R, Roggi C, Cena H (2014) n-3 LC-PUFA supplementation: effects on infant and maternal outcomes. Eur J Nutr 53:1147–1154. doi:10.1007/s00394-014-0660-9

Leventakou V, Roumeliotaki T, Martinez D et al (2014) Fish intake during pregnancy, fetal growth, and gestational length in 19 European birth cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr 99:506–516. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.067421

Harvey NC, Holroyd C, Ntani G et al (2014) Vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 18:1–190. doi:10.3310/hta18450

Asemi Z, Hashemi T, Karamali M et al (2013) Effects of vitamin D supplementation on glucose metabolism, lipid concentrations, inflammation, and oxidative stress in gestational diabetes: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr 98:1425–1432. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.072785

Catov JM, Bodnar LM, Olsen J et al (2011) Periconceptional multivitamin use and risk of preterm or small-for-gestational-age births in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 94:906–912. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.012393

Asemi Z, Samimi M, Tabassi Z et al (2014) Multivitamin versus multivitamin-mineral supplementation and pregnancy outcomes: a single-blind randomized clinical trial. Int J Prev Med 5:439–446

Alwan NA, Greenwood DC, Simpson NA et al (2010) The relationship between dietary supplement use in late pregnancy and birth outcomes: a cohort study in British women. BJOG 117:821–829. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02549

Carlson SE, Colombo J, Gajewski BJ et al (2013) DHA supplementation and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr 97:808–815. doi:10.3945/ajcn.112.050021

Food Safety Authority of Ireland (2011) Scientific recommendations for healthy eating guidelines in Ireland. FSAI, Dublin

Health Service Executive and Institute of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (2013) Clinical practice guideline–nutrition for pregnancy. Dublin, HSE

National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) (2013) Healthy eating during your pregnancy––advice on eating for you and your baby (N55F). Government of Australia, Canberra

Pick ME, Edwards M, Moreau D et al (2012) Prepregnancy adherence to dietary patterns and lower risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr 96:289–295. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.028266

Melere C, Hoffmann JF, Nunes MA et al (2013) Healthy eating index for pregnancy: adaptation for use in pregnant women in Brazil. Rev Saude Public 47:20–28

Shin D, Bianchi L, Chung H et al (2014) Is gestational weight gain associated with diet quality during pregnancy? Matern Child Health J 18:1433–1443. doi:10.1007/s10995-013-1383

Livingstone MB, Black AE (2003) Markers of the validity of reported energy intake. J Nutr 133:895S–920S

Black AE (2000) Critical evaluation of energy intake using the Goldberg cut-off for energy intake: basal metabolic rate. A practical guide to its calculation, use and limitations. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 24:1119–1130

Henry CJ (2005) Basal metabolic rate studies in humans: measurement and development of new equations. Public Health Nutr 8:1133–1152

Goldberg GR, Black AE, Jebb SA et al (1991) Critical evaluation of energy intake data using fundamental principles of energy physiology: derivation of cut-off limits to identify under-recording. Eur J Clin Nutr 45:569–581

Black AE, Coward WA, Cole TJ et al (1996) Human energy expenditure in affluent societies: an analysis of 574 doubly-labelled water measurements. Eur J Clin Nutr 50:72–92

Wearne SJ, Day MJL (1999) Clues for the development of food-based dietary guidelines: how are dietary targets being achieved by UK consumers? Br J Nutr 81:S119–S126

Harrington KE, McGowan MJ, Kiely M et al (2001) Macronutrient intakes and food sources in Irish adults: findings of the North/South Ireland Food Consumption Survey. Public Health Nutr 4:1051–1060

Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital (2014) Annual clinical report 2014. CWIUH, Dublin

The Economic and Social Research Institute (2012) Perinatal Statistics Report 2012. ESRI, Dublin

Bowers K, Tobias DK, Yeung E et al (2012) A prospective study of prepregnancy dietary fat intake and risk of gestational diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr 95:446–453. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.026294

Alati R, Davey Smith G, Lewis SJ et al (2013) Effect of prenatal alcohol exposure on childhood academic outcomes: contrasting maternal and paternal associations in the ALSPAC study. PLoS ONE 8:e74844. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074844

Baddour SE, Virasith H, Vanstone C et al (2013) Validity of the Willett food frequency questionnaire in assessing the iron intake of French-Canadian pregnant women. J Nutr 29:752–756. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2012.12.019

Messina M, Lampe JW, Birt DF et al (2002) Reductionism and the narrowing nutrition perspective: time for reevaluation and emphasis on food synergy. J Am Diet Assoc 101:1416–1419

Farchi G, Mariotti S, Menotti A et al (1989) Diet and 20-y mortality in two rural population groups of middle-aged men in Italy. Am J Clin Nutr 50:1095–1103

Newby PK, Tucker KL (2004) Empirically derived eating patterns using factor or cluster analysis: a review. Nutr Rev 62:177–203

Central Statistics Office (2012) Information Society Statistics: Households 2012. Central Statistics Office, Ireland 2012 (Internet http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/releasespublications/documents/informationtech/2012/isth_2012.pdf). Accessed 20 March 2013

Pick ME, Edwards M, Moreau D et al (2005) Assessment of diet quality in pregnant women using the Healthy Eating Index. J Am Diet Assoc 105:240–246

Bodnar LM, Siega-Riz AM (2002) A Diet Quality Index for Pregnancy detects variation in diet and differences by sociodemographic factors. Public Health Nutr 5:801–809

Rifas-Shiman SL, Rich-Edwards JW, Kleinman KP et al (2009) Dietary quality during pregnancy varies by maternal characteristics in project viva: a US cohort. J Am Diet Assoc 109:1004–1011

Fowles ER, Gentry B (2008) The feasibility of personal digital assistants (PDAs) to collect dietary intake data in low-income pregnant women. J Nutr Educ Behav 40:374–377

Prentice RL, Massavar-Rahmani Y, Huang Y et al (2011) Evaluation and comparison of food records, recalls, and frequencies for energy and protein assessment by using recovery biomarkers. Am J Epidemiol 17:591–603. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr140

Atkinson NL, Gold RS (2002) The promise and challenge of eHealth interventions. Am J Health Behav 26:494–503

Department of Health (DoH) (1991) dietary reference values for food energy and nutrients for the United Kingdom. Report on health and social subjects, No 41. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (HMSO)

Department of Health (2016) UK Chief Medical Officers’ alcohol guidelines review summary of the proposed new guidelines. DOH, UK

Food Safety Authority of Ireland (1999) Recommended dietary allowances for Ireland 1999. FSAI, Dublin

Food Safety Authority of Ireland (2005) Salt and health: review of the scientific evidence and recommendations for public policy in Ireland. FSAI, Dublin

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge with gratitude the participation and cooperation of the pregnant women who participated in this study. This project was gratefully supported by an unrestricted educational grant provided by Danone Nutricia Early Life Nutrition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

LM, ACOH, SC, RK and MJT declare no conflict of interest. DMcC developed the online dietary assessment tool (DAT) and is the proprietary owner of this technology and the intellectual property embedded in it (outlined in conflict of interest form).

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mullaney, L., O’Higgins, A.C., Cawley, S. et al. Use of a web-based dietary assessment tool in early pregnancy. Ir J Med Sci 185, 341–355 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-016-1430-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-016-1430-x