Abstract

Introduction

Sepsis is a leading cause of death in the critically ill patient. It is a heterogeneous disease and it is frequently difficult to make an unequivocal and expeditious diagnosis. The current ‘gold standard’ in diagnosing sepsis is the blood culture but this is only available after a significant time delay. Mortality rates from sepsis remain high, however, the introduction of sepsis care bundles in its management has produced significant improvements in patient outcomes. Central to goal-directed resuscitation is the timely and accurate diagnosis of sepsis. The rapid diagnosis and commencement of the appropriate therapies has been shown to reduce the mortality.

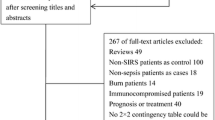

Materials and methods

Biomarkers are already used in clinical practice to aid other more traditional diagnostic tests. In the absence of an adequate gold standard to diagnose sepsis, there has been considerable and growing interest in trying to identify suitable biomarkers. There is currently an unmet need in the medical literature to communicate the importance of the challenges relating to the rapid diagnosis and implementation of goal-directed therapy in sepsis and the underlying concepts that are directing these investigations. This article reviews the more novel biomarkers investigated to differentiate systemic inflammatory response syndrome from sepsis.

Conclusion

The biomarkers described reflect the difficulties in making evidence-based recommendations particularly when interpreting studies where the methodology is of poor quality and the results are conflicting. We are reminded of our responsibilities to ensure high quality and standardised study design as articulated by the STAndards for the Reporting of Diagnostic accuracy studies (STARD) initiative.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL et al (2006) Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med 34(2):344–353

Harrison DA, Welch CA, Eddleston JM (2006) The epidemiology of severe sepsis in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 1996 to 2004: secondary analysis of a high quality clinical database, the ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database. Crit Care 10(2):R42

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM et al (2008) Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Med 34:17–60

Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR et al (2010) Surviving Sepsis Campaign: the surviving sepsis campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 38:367–374

Lever A, Mackenzie I (2007) Sepsis: definition, epidemiology, and diagnosis. BMJ 335:879–883

American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference (1992) Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med 20:864–874

Vincent JL (1997) Dear SIRS, Im sorry to say that I don’t like you. Crit Care Med 25(2):372–374

Bossink AW, Groeneveld J, Hack CE, Thijs LG (1998) Prediction of mortality in febrile medical patients: how useful are systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis criteria? Chest 113(6):1533–1541

Pizzo PA (1989) Evaluation of fever in the patient with cancer. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 25(Suppl 2):S9–S16

Muller B, Becker KL, Schachinger H et al (2000) Calcitonin precursors are reliable markers of sepsis in a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 28:977–983

Young LS (1990) Gram-negative sepsis. In: Mandell GL, Douglas RDJ, Bennett JE (eds) Principles and practice of infectious diseases, pp 611–636 Churchill Livingstone, New York

Leibovici L, Shagra I, Drucker M, Konigsberger H, Samra Z, Pitlik SD (1998) The benefit of appropriate empirical antibiotic treatment in patients with bloodstream infections. J Intern Med 244:379–386

Zambon M, Ceola M, Almeida-de-Castro R, Gullo A, Vincent JL (2008) Implementation of the surviving sepsis campaign guidelines for severe sepsis and septic shock: we could go faster. J Crit Care 23:455–460

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM et al (2008) Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med 36:296–327

Mylonakis E, Ryan ET, Calderwood SB (2001) Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a review. Arch Intern Med 161(4):525–533

Pierrakos C, Vincent JL (2010) Sepsis biomarkers: a review. Crit Care 14(1):R15 (epub 2010)

Cicarelli DD, Vieira JE, Benseñor FE (2009) C-reactive protein is not a useful indicator for infection in surgical intensive care units. Sao Paulo Med J 127(6):350–354

Bouchon A, Facchetti F, Weigand MA, Colonna M (2001) TREM-1 amplifies inflammation and is a crucial mediator of septic shock. Nature 410:1103–1107

Gibot S, Kolopp-Sarda MN, Bene MC et al (2004) Plasma level of a triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1: Its diagnostic accuracy in patients with suspected sepsis. Ann Intern Med 141:9–15

Liao R, Liu Z, Wei S, Xu F, Chen Z, Gong J (2009) Triggering receptor in myeloid cells (TREM-1) specific expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of sepsis patients with acute cholangitis. Inflammation 32(3):182–190

Bopp C, Hofer S, Bouchon A, Zimmermann JB, Martin E, Weigand MA (2009) Soluble TREM-1 is not suitable for distinguishing between systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis survivors and nonsurvivors in the early stage of acute inflammation. Eur J Anaesthesiol 26(6):504–507

Barati M, Bashar FR, Shahrami R, Zadeh MH, Taher MT, Nojomi M (2010) Soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 and the diagnosis of sepsis. J Crit Care 25(2):362.e1–362.e6

Stöve S, Welte T, Wagner TO et al (1996) Circulating complement proteins in patients with sepsis or systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 3(2):175–183

Selberg O, Hecker H, Martin M, Klos A, Bautsch W, Köhl J (2000) Discrimination of sepsis and systemic inflammatory response syndrome by determination of circulating plasma concentrations of procalcitonin, protein complement 3a, and interleukin-6. Crit Care Med 28(8):2793–2798

Ruiz-Alvarez MJ, García-Valdecasas S, De Pablo R et al (2009) Diagnostic efficacy and prognostic value of serum procalcitonin concentration in patients with suspected sepsis. J Intensive Care Med 24(1):63–71

Abidi K, Khoudri I, Belayachi J et al (2008) Eosinopenia is a reliable marker of sepsis on admission to medical intensive care units. Crit Care 12(2):R59

Wang H, Cheng B, Chen Q et al (2008) Time course of plasma gelsolin concentrations during severe sepsis in critically ill surgical patients. Crit Care 12(4):R106

Cummings CJ, Sessler CN, Beall LD, Fisher BJ, Best AM, Fowler AA (1997) Soluble E-selectin levels in sepsis and critical illness. Correlation with infection and hemodynamic dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156(2 Pt 1):431–437

Punyadeera C, Schneider EM, Schaffer D et al (2010) A biomarker panel to discriminate between systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis and sepsis severity. J Emerg Trauma Shock 3(1):26–35

Vaschetto R, Nicola S, Olivieri C et al (2008) Serum levels of osteopontin are increased in SIRS and sepsis. Intensive Care Med 34(12):2176–2184

Hattori N, Oda S, Sadahiro T et al (2009) YKL-40 identified by proteomic analysis as a biomarker of sepsis. Shock 32(4):393–400

Muller B, Peri G, Doni A et al (2001) Circulating levels of the long pentraxin PTX3 correlate with severity of infection in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 29(7):1404–1407

Al-Ramadi BK, Ellis M, Pasqualini F, Mantovani A (2004) Selective induction of pentraxin 3, a soluble innate immune pattern recognition receptor, in infectious episodes in patients with haematological malignancy. Clin Immunol 112(3):221–224

Hofer S, Brenner T, Bopp C et al (2009) Cell death serum biomarkers are early predictors for survival in severe septic patients with hepatic dysfunction. Crit Care 13(3):R93

Wang JF, Yu ML, Yu G et al (2010) Serum miR-146a and miR-223 as potential new biomarkers for sepsis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 394(1):184–188

Yousef AA, Amr YM, Suliman GA (2010) The diagnostic value of serum leptin monitoring and its correlation with tumor necrosis factor-alpha in critically ill patients: a prospective observational study. Crit Care 14(2):R33

Ruiz Martín G, Prieto Prieto J, Veiga de Cabo J et al (2004) Plasma fibronectin as a marker of sepsis. Int J Infect Dis 8(4):236–243

Saito K, Wagatsuma T, Toyama H et al (2008) Sepsis is characterised by the increase in percentages of circulating CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells and plasma levels of soluble CD25. Tokoku J Exp Med 216:61–68

Hein F, Massin F, Cravoisy-Popovic A, Barraud D, Levy B, Bollaert PE (2010) The relationship between CD4+CD25+CD127-regulatory T cells and inflammatory response and outcome during shock states. Crit Care 14(1):R19

Cursons RT, Jeyerajah E, Sleigh JW (1999) The use of polymerase chain reaction to detect septicemia in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 27:937–940

Dark PM, Dean P, Washurst G (2009) Bench-to-bedside review: the promise of rapid infection diagnosis during sepsis using polymerase chain reaction-based pathogen detection. Crit Care 13(4):217

Louie RF, Tang Z, Albertson TE, Cohen S, Tran NK, Kost GJ (2008) Multiplex polymerase chain reaction detection enhancement of bacteremia and fungemia. Crit Care Med 36:1487–1492

Clyne B, Olshaker JS (1999) The C-reactive protein. J Emerg Med 17:1019–1025

Jaimes F, Arango C, Ruiz G et al (2004) Predicting bacteremia at the bedside. Clin Infect Dis 38:357–362

Povoa P, Almeida E, Moreira P et al (1998) C-reactive protein as an indicator of sepsis. Intensive Care Med 24:1052–1056

Uzzan B, Cohen R, Nicolas P, Cucherat M, Perret GY (2006) Procalcitonin as a diagnostic test for sepsis in critically ill adults and after surgery or trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 37(7):1996–2003

Simon L, Gauvin F, Amre DK, Saint-Louis P, Lacroix J (2004) Serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels as markers of bacterial infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 39:206–217

Wolff M, Bouadma L (2010) What procalcitonin brings to management of sepsis in the ICU. Crit Care 14(6):1007 (epub 2010)

Tang H, Huang T, Jing J, Shen H, Cui W (2009) Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment in patients with infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infection 37(6):497–507 (epub 2009)

Bozza FA, Salluh JI, Japiassu AM et al (2007) Cytokine profiles as markers of disease severity in sepsis: a multiplex analysis. Crit Care 11:R49

Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S, Hollander JE et al (2009) A prospective, multicenter derivation of a biomarker panel to assess risk of organ dysfunction, shock, and death in emergency department patients with suspected sepsis. Crit Care Med 37:96–104

Marshall JC, Reinhart K, for the International Sepsis Forum (2009) Biomarkers of sepsis. Crit Care Med 37(7):2290–2298

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hall, T.C., Bilku, D.K., Al-Leswas, D. et al. Biomarkers for the differentiation of sepsis and SIRS: the need for the standardisation of diagnostic studies. Ir J Med Sci 180, 793–798 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-011-0741-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-011-0741-1