Abstract

Purpose

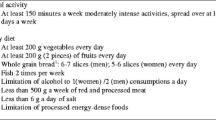

Assess feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of an integrated symptom management and lifestyle intervention (SMLI) to improve adherence to the American Cancer Society’s (ACS) Guidelines on Nutrition and Physical Activity in Latina cancer survivors and their informal caregivers (dyads).

Methods

Forty-five dyads were randomized to a 12-week telephone-delivered intervention or attention control. Intervention effects on nutrition, physical activity, symptom burden, and self-efficacy for symptom management were estimated using Cohen’s ds.

Results

Mean age was 64 for survivors and 53 for caregivers. Feasibility was demonstrated by the 63% consent rate out of approached dyads. The SMLI was acceptable for 98% of dyads. Among survivors, medium-to-large effect sizes were found for increased servings of total fruits and vegetables (d = 0.55), vegetables (d = 0.72), and decreased sugar intake (d = − 0.51) and medium clinically significant effect sizes for total minutes of physical activity per week (d = 0.42) and grams of fiber intake per day (d = 0.40) for intervention versus attention control. Additionally, medium-to-large intervention effects were found for the reduction of symptom burden (d = 0.74). For caregivers, medium-to-large intervention effects were found for reduced total sugar intake (d = − 0.60) and sugar intake from sugar-sweetened beverages (d = − 0.65); vegetable intake was increased with a medium effect size (d = 0.41).

Conclusion

SMLI was feasible and acceptable for both dyadic members. A larger, well-powered trial is needed to formally evaluate SMLI effectiveness.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Integrating symptom management with lifestyle behavior interventions may increase adherence to the ACS guidelines on nutrition and physical activity to prevent new and recurrent cancers.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Noe-Bustamante LL, Lopez, MH, Krogstad, JM. U.S. Hispanic population surpassed 60 million in 2019, but growth has slowed. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/07/u-s-hispanic-population-surpassed-60-million-in-2019-but-growth-has-slowed/. Published 2020, July 7. Accessed Aug 8, 2020.

Society AC. Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2018–2020. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc.; 2018.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30.

Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief 2017(288):1–8.

Islami F, Goding Sauer A, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):31–54.

Song M, Giovannucci E. Preventable incidence and mortality of carcinoma associated with lifestyle factors among white adults in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(9):1154–61 PMC5016199.

Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, Rock CL, Demark-Wahnefried W, Bandera EV, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):30–67.

Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K. Cancer survivors' adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society's SCS-II. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(13):2198–204.

Inoue-Choi M, Robien K, Lazovich D. Adherence to the WCRF/AICR guidelines for cancer prevention is associated with lower mortality among older female cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomarkers. 2013;22(5):792–802.

Kohler LN, Garcia DO, Harris RB, Oren E, Roe DJ, Jacobs ET. Adherence to diet and physical activity cancer prevention guidelines and cancer outcomes: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2016;25(7):1018–28 PMC4940193.

Kohler LN, Harris RB, Oren E, Roe DJ, Lance P, Jacobs ET. Adherence to nutrition and physical activity cancer prevention guidelines and development of colorectal adenoma. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):PMC6115749.

Park SH, Knobf MT, Kerstetter J, Jeon S. Adherence to American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity in female cancer survivors: results from a randomized controlled trial (Yale Fitness Intervention Trial). Cancer Nurs. 2019;42(3):242–50 PMC6226367.

Thomson CA, McCullough ML, Wertheim BC, et al. Nutrition and physical activity cancer prevention guidelines, cancer risk, and mortality in the women's health initiative. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2014;7(1):42–53 PMC4090781.

Greenlee H, Molmenti CL, Crew KD, et al. Survivorship care plans and adherence to lifestyle recommendations among breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(6):956–63.

Byrd DA, Agurs-Collins T, Berrigan D, Lee R, Thompson FE. Racial and ethnic differences in dietary intake, physical activity, and body mass index (BMI) among cancer survivors: 2005 and 2010 National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS). J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(6):1138–46.

Dieli-Conwright CM, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise on metabolic syndrome, sarcopenic obesity, and circulating biomarkers in overweight or obese survivors of breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(9):875–83 PMC5858524.

Dieli-Conwright CM, Sweeney FC, Courneya KS, et al. Hispanic ethnicity as a moderator of the effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in survivors of breast cancer. Cancer. 2019;125(6):910–20 PMC7164690.

Morey MC, Snyder DC, Sloane R, Cohen HJ, Peterson B, Hartman TJ, et al. Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, Overweight Long-term Cancer Survivors. JAMA. 2009;301(18):1883–91.

Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Caan BJ, Parker BA, Greenberg ER, Flatt SW, et al. Influence of a diet very high in vegetables, fruit, and fiber and low in fat on prognosis following treatment for breast cancer. JAMA. 2007;298(3):289–98.

Spark LC, Reeves MM, Fjeldsoe BS, Eakin EG. Physical activity and/or dietary interventions in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of the maintenance of outcomes. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(1):74–82.

Cleeland CS, Zhao F, Chang VT, et al. The symptom burden of cancer: evidence for a core set of cancer-related and treatment-related symptoms from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Symptom Outcomes and Practice Patterns study. Cancer. 2013;119(24):4333–40 PMC3860266.

Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Lu C, et al. Measuring the symptom burden of lung cancer: the validity and utility of the lung cancer module of the M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Oncologist. 2011;16(2):217–27 PMC3228083.

Alfano CM, Smith AW, Irwin ML, et al. Physical activity, long-term symptoms, and physical health-related quality of life among breast cancer survivors: a prospective analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1(2):116–28 PMC2996230.

Cho MH, Dodd MJ, Cooper BA, Miaskowski C. Comparisons of exercise dose and symptom severity between exercisers and nonexercisers in women during and after cancer treatment. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2012;43(5):842–54 PMC3348465.

Hardcastle SJ, Maxwell-Smith C, Kamarova S, Lamb S, Millar L, Cohen PA. Factors influencing non-participation in an exercise program and attitudes towards physical activity amongst cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(4):1289–95.

Stanton AL, Bernaards CA, Ganz PA. The BCPT symptom scales: a measure of physical symptoms for women diagnosed with or at risk for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(6):448–56.

Howard-Anderson J, Ganz PA, Bower JE, Stanton AL. Quality of life, fertility concerns, and behavioral health outcomes in younger breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(5):386–405.

Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, Krupnick JL, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Quality of life at the end of primary treatment of breast cancer: first results from the moving beyond cancer randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(5):376–87.

Stanton AL, Ganz PA, Kwan L, Meyerowitz BE, Bower JE, Krupnick JL, et al. Outcomes from the moving beyond cancer psychoeducational, randomized, controlled trial with breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):6009–18.

Bower JE, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Kwan L, Breen EC, Cole SW. Inflammation and behavioral symptoms after breast cancer treatment: do fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbance share a common underlying mechanism? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(26):3517–22.

Owen JE, O'Carroll Bantum E, Pagano IS, Stanton A. Randomized trial of a social networking intervention for cancer-related distress. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(5):661–72 PMC5572555.

Badger TA, Segrin C, Hepworth JT, Pasvogel A, Weihs K, Lopez AM. Telephone-delivered health education and interpersonal counseling improve quality of life for Latinas with breast cancer and their supportive partners. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(5):1035–42.

Baruth M, Wilcox S, Ananian CD, Heiney S. Effects of home-based walking on quality of life and fatigue outcomes in early stage breast cancer survivors: a 12-week pilot study. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(s1):S110–8.

Cheville AL, Kollasch J, Vandenberg J, Shen T, Grothey A, Gamble G, et al. A home-based exercise program to improve function, fatigue, and sleep quality in patients with stage IV lung and colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2013;45(5):811–21.

Kampshoff CS, Chinapaw MJ, Brug J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of high intensity and low-to-moderate intensity exercise on physical fitness and fatigue in cancer survivors: results of the Resistance and Endurance exercise After ChemoTherapy (REACT) study. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):275.

Velthuis M, Agasi-Idenburg S, Aufdemkampe G, Wittink H. The effect of physical exercise on cancer-related fatigue during cancer treatment: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Oncol. 2010;22(3):208–21.

Kwiatkowski F, Mouret-Reynier M, Duclos M, Leger-Enreille A, Bridon F, Hahn T, et al. Long term improved quality of life by a 2-week group physical and educational intervention shortly after breast cancer chemotherapy completion. Results of the ‘Programme of Accompanying women after breast Cancer treatment completion in Thermal resorts’(PACThe) randomised clinical trial of 251 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(7):1530–8.

Stevinson C, Steed H, Faught W, Tonkin K, Vallance JK, Ladha AB, et al. Physical activity in ovarian cancer survivors: associations with fatigue, sleep, and psychosocial functioning. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19(1):73–8.

Cramer H, Pokhrel B, Fester C, Meier B, Gass F, Lauche R, et al. A randomized controlled bicenter trial of yoga for patients with colorectal cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2016;25(4):412–20.

Rao MR, Raghuram N, Nagendra H, et al. Anxiolytic effects of a yoga program in early breast cancer patients undergoing conventional treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2009;17(1):1–8.

Courneya KS, McKenzie D, Gelmon KA, et al. A multicenter randomized trial of the effects of exercise dose and type on psychosocial distress in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomarkers. 2014:cebp. 1163.2013.

Sun V, Grant M, McMullen CK, et al. Surviving colorectal cancer: long-term, persistent ostomy-specific concerns and adaptations. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2013;40(1):61.

Ravasco P, Monteiro-Grillo I, Camilo M. Individualized nutrition intervention is of major benefit to colorectal cancer patients: long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of nutritional therapy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(6):1346–53.

Zick SM, Colacino J, Cornellier M, Khabir T, Surnow K, Djuric Z. Fatigue reduction diet in breast cancer survivors: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;161(2):299–310.

Harding R, Epiphaniou E, Hamilton D, Bridger S, Robinson V, George R, et al. What are the perceived needs and challenges of informal caregivers in home cancer palliative care? Qualitative data to construct a feasible psycho-educational intervention. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(9):1975–82.

Hartmann M, Bäzner E, Wild B, Eisler I, Herzog W. Effects of interventions involving the family in the treatment of adult patients with chronic physical diseases: a meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79(3):136–48.

Martire LM, Lustig AP, Schulz R, Miller GE, Helgeson VS. Is it beneficial to involve a family member? A meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Health Psychol. 2004;23(6):599–611.

Martire LM, Helgeson VS. Close relationships and the management of chronic illness: associations and interventions. Am Psychol. 2017;72(6):601–12 PMC5598776.

Shields CG, Finley MA, Chawla N, Meadors WP. Couple and family interventions in health problems. J Marital Fam Ther. 2012;38(1):265–80.

Beesley VL, Janda M, Eakin EG, Auster JF, Chambers SK, Aitken JF, et al. Gynecological cancer survivors and community support services: referral, awareness, utilization and satisfaction. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19(1):54–61.

Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, Pinto BM. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5814–30 PMC1550285.

Ganz PA. A teachable moment for oncologists: cancer survivors, 10 million strong and growing! J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5458–60.

Chandrasekar D, Tribett E, Ramchandran K. Integrated palliative care and oncologic care in non-small-cell lung cancer. Curr Treat Options in Oncol. 2016;17(5):23 PMC4819778.

NCCN Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Palliative Care. National Comprehensive Cancer Network;2020.

Bandura AJEC, NJ. Social foundations of thought and action. 1986;1986.

Loprinzi PD, Cardinal BJ. Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between behavioral processes of change and physical activity in older breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer. 2013;20(1):47–52.

Stacey FG, James EL, Chapman K, Courneya KS, Lubans DR. A systematic review and meta-analysis of social cognitive theory-based physical activity and/or nutrition behavior change interventions for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(2):305–38 PMC4441740.

Packel LB, Prehn AW, Anderson CL, Fisher PL. Factors influencing physical activity behaviors in colorectal cancer survivors. Am J Health Promot. 2015;30(2):85–92.

Crane TE, Parizek D, Eddy N, et al. Ehealth and intervention platform. In: Google Patents; 2018.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Frongillo EA Jr. Validation of measures of food insecurity and hunger. J Nutr. 1999;129(2S Suppl):506s–9s.

Gany F, Lee T, Ramirez J, et al. Do our patients have enough to eat?: food insecurity among urban low-income cancer patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25(3):1153–68 PMC4849892.

Thompson FE, Subar AF, Smith AF, et al. Fruit and vegetable assessment: performance of 2 new short instruments and a food frequency questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(12):1764–72.

Wakimoto P, Block G, Mandel S, Medina N. Development and reliability of brief dietary assessment tools for Hispanics. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(3):A95 PMC1637803.

Meyer AM, Evenson KR, Morimoto L, Siscovick D, White E. Test-retest reliability of the Women's Health Initiative physical activity questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):530–8 PMC2692735.

Badger TA, Segrin C, Meek P. Development and validation of an instrument for rapidly assessing symptoms: the general symptom distress scale. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2011;41(3):535–48 3062688.

Correia H. Spanish translations of PROMIS instruments. Northwestern University, Dept of Medical Social Sciences. 2011.

Holmstrom AJ, Wyatt GK, Sikorskii A, Musatics C, Stolz E, Havener N. Dyadic recruitment in complementary therapy studies: experience from a clinical trial of caregiver-delivered reflexology. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;29:136–9 PMC4748168.

Voils CI, King HA, Maciejewski ML, Allen KD, Yancy WS Jr, Shaffer JA. Approaches for informing optimal dose of behavioral interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2014;48(3):392–401 PMC4414086.

Bandura A, Freeman W, Lightsey R. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. In: Springer; 1999.

Sloan JA, Cella D, Hays RD. Clinical significance of patient-reported questionnaire data: another step toward consensus. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(12):1217–9.

Nayak P, Paxton RJ, Holmes H, Nguyen HT, Elting LS. Racial and ethnic differences in health behaviors among cancer survivors. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(6):729–36.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services USDoA. 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015.

Mama SK, Song J, Ortiz A, et al. Longitudinal social cognitive influences on physical activity and sedentary time in Hispanic breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2017;26(2):214–21 PMC4879102.

Kroenke K. Studying symptoms: sampling and measurement issues. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(9 Pt 2):844–53.

Koffel E, Kats AM, Kroenke K, et al. Sleep disturbance predicts less improvement in pain outcomes: secondary analysis of the SPACE randomized clinical trial. Pain Med. 2020;21(6):1162–7 PMC7069777.

Crane TE, Badger TA, Sikorskii A, Segrin C, Hsu CH, Rosenfeld AG. Trajectories of depression and anxiety in Latina breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2019;46(2):217–27 PMID30767959.

Badger TA, Segrin C, Sikorskii A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of supportive care interventions to manage psychological distress and symptoms in Latinas with breast cancer and their informal caregivers. Psychol Health. 2020;35(1):87–106 PMID31189338.

Kroenke K, Baye F, Lourens SG, et al. Automated self-management (ASM) vs. ASM-enhanced collaborative care for chronic pain and mood symptoms: the CAMMPS randomized clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1806–14 PMC6712242.

Fletcher BS, Miaskowski C, Given B, Schumacher K. The cancer family caregiving experience: an updated and expanded conceptual model. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(4):387–98 PMC3290681.

American Cancer Society. Family Caregivers. 2011.

Yabroff KR, Kim Y. Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4362–73.

Gaugler JE, Kane RL, Kane RA, Newcomer R. Predictors of institutionalization in Latinos with dementia. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2006;21(3–4):139–55.

Marquez JA, Ramírez García JI. Family caregivers' narratives of mental health treatment usage processes by their Latino adult relatives with serious and persistent mental illness. J Fam Psychol. 2013;27(3):398–408.

John R, Resendiz R, De Vargas LW. Beyond familism?: familism as explicit motive for eldercare among Mexican American caregivers. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 1997;12(2):145–62.

Jutagir DR, Gudenkauf LM, Stagl JM, et al. Ethnic differences in types of social support from multiple sources after breast cancer surgery. Ethn Health. 2016;21(5):411–25 PMC4731323.

Bernard-Davila B, Aycinena AC, Richardson J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to recruitment to a culturally-based dietary intervention among urban Hispanic breast cancer survivors. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(2):244–55 PMC4636022.

Funding

This work was supported by the American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant (128749-IRG-16-124-37-IRG) (Crane) and Behavioral Measurement and Interventions Shared Resource at the University of Arizona Cancer Center Support Grant National Cancer Institute (P30 CA023074).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crane, T.E., Badger, T.A., O’Connor, P. et al. Lifestyle intervention for Latina cancer survivors and caregivers: the Nuestra Salud randomized pilot trial. J Cancer Surviv 15, 607–619 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00954-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00954-z