Abstract

Purpose

There is a paucity of formal clinician education concerning cancer survivorship care, which produces care barriers and poorer outcomes for survivors of childhood cancer. To address this, we implemented a curriculum in childhood cancer survivorship care for pediatric residents at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). We examined the efficacy of this curriculum following program completion.

Methods

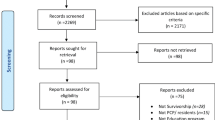

A case-based curriculum was created and integrated within existing educational structures using Kern’s model. We utilized the retrospective pre-posttest method to evaluate participating residents’ knowledge, clinical skills, and attitudes towards cancer survivorship topics before and after receiving the curriculum. Pre-posttest items were compared using paired t tests and one-sided binomial tests. We analyzed free-response question items for major themes using constant comparative methods.

Results

Thirty-four residents completed the curriculum and its evaluation. Each assessment item significantly increased from pre- to post-curriculum; p < 0.05. Greater than 40% of residents improved in all but one assessment item post-curriculum; p < 0.05. Residents reported the curriculum enhanced their pediatric knowledge base (M = 3.24; SD = 0.65) and would recommend it to other residency programs; M = 3.24; SD = 0.69. Major themes included residents’ request for additional oncofertility information, training in counseling survivors, and cancer survivorship training opportunities.

Conclusions

A cancer survivorship curriculum can successfully increase trainees’ knowledge, clinical skills, and comfort in discussing topics relevant to survivorship care.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

With increasing numbers of childhood cancer survivors living into adulthood, residents will likely treat this population regardless of intended career path. This curriculum represents one method to deliver formal cancer survivorship training.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Phillips SM, Padget LS, Leisenring WM, et al. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2015;24(4):653–63.

Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al (eds). SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2014. In: National Cancer Institute Reports on Cancer. National Cancer Institute. 2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/. Accessed 15 May 2017.

Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Childhood cancer survivor study: chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–82.

Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, Gurney JG, Casillas J, Chen H, et al. Health care of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(1):61–70.

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hematology/ Oncology, Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up care for pediatric cancer survivors. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):906–15.

Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Mahoney MC, et al. Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4401–9.

Mertens AC, Cotter KL, Foster BM, Zebrack BJ, Hudson MM, Eshelman D, et al. Improving health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer: recommendations from a Delphi panel of health policy experts. Health Policy. 2004;69:169–78.

Nathan PC, Daugherty CK, Wroblewski KE, Kigin ML, Stewart TV, Hlubocky FJ, et al. Family physician preferences and knowledge gaps regarding the care of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):275–82.

Suh E, Daugherty CK, Wroblewski KE, et al. General internists’ preferences and knowledge about the care of adult survivors of childhood cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(1):11–7.

Zebrack BJ, Eshelman DA, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Cotter KL, Foster BM, et al. Health care for childhood cancer survivors: insights and perspectives from a Delphi panel of young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2004;100(4):843–50.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006.

Shayne M, Culakova E, Milano MT, Dhakal S, Constine LS. The integration of cancer survivorship training in the curriculum of hematology/oncology fellows and radiation oncology residents. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(2):167–72.

Uijtdehaage S, Hauer KE, Stuber M, Liang Go V, Rajagopalan S, Wilkerson L. Preparedness for caring of cancer survivors: a multi-institutional study of medical students and oncology fellows. J Cancer Educ. 2009;24(1):28–32.

Nathan PC, Schiffman JD, Huang S, Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman-Kent D, et al. Childhood cancer survivorship educational resources in North American pediatric hematology/oncology fellowship training programs: a survey study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:1186–90.

American Board of Pediatrics. Hematology and oncology. In: Goals and objectives by competency and level of training. American Board of Pediatrics. 2014. http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/9ebadf_89800da775c54d4f909f79eef7352b5d.pdf. Accessed on 10 Sept 2015.

Kern DE, Thomas PA, Hughes MT. Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. 2nd ed. Baltimore: The John’s Hopkins University Press; 2009.

McLean S. Case-based learning and its application in medical and health-care fields: a review of worldwide literature. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2016;3:39–49.

Srinivasan M, Wilkes M, Stevenson F, Nguyen T, Slavin S. Comparing problem-based learning with case-based learning: effects of a major curricular shift at two institutions. Acad Med. 2007;82:74–82.

Talwalkar JS, Fenick AM. Evaluation of a case-based primary care pediatric conference curriculum. J Grad Med Educ. 2011 Jun;3(2):224–31.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. Childhood cancer survivorship: improving care and quality of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003.

Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers (Version 4.0). Children’s Oncology Group. 2013. www.survivorshipguidelines.org. Accessed on 9 November 2015.

Compas BE, Jaser SS, Dunn MJ, Rodriguez EM. Coping with chronic illness in childhood and adolescence. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:455–80.

Turkel S, Pao M. Late consequences of pediatric chronic illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(4):819–35.

Bloom BS, Engelhart MD, Furst EJ, et al. Taxonomy of educational objectives: the classification of educational goals. Handbook I: cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company; 1956.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in pediatrics. ACGME. 2017. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/320_pediatrics_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed on 1 July 2017.

Howard GS, Ralp KM, Gulanick NA, et al. Internal invalidity in pretest-posttest self-report evaluations and a re-evaluation of retrospective pretests. Appl Psychol Meas. 1979;3(1):1–23.

Howard GS. Response-shift bias: a problem in evaluating interventions with pre/post self-reports. Eval Rev. 1980;4(1):93–106.

Lam TC, Bengo P. A comparison of three retrospective self-reporting methods of measuring change in instructional practice. Am J Eval. 2003;24(1):65–80.

Pratt CC, McGuigan WM, Katzev AR. Measuring program outcomes: using retrospective pretest methodology. Am J Eval. 2000;21(3):341–9.

Allen JM, Nimon K. A retrospective pretest: a practical technique for professional development evaluation. J Ind Teach Educ. 2007;44:27–42.

Bhanji F, Gottesman R, de Grave W, Steinert Y, Winer LR. The retrospective pre-post: a practical method to evaluate learning from an educational program. Acad Emerg Med. 2012 Feb;19(2):189–94.

Skeff KM, Bergen MR, Stratos GA. Evaluation of a medical faculty development program: a comparison of traditional pre/post and retrospective pre/post self-assessment ratings. Eval Health Prof. 1992;15:350–66.

Clasen DL, Dormody TJ. Analyzing data measured by individual Likert-type items. J Agric Educ. 1994;35(4):31–5.

Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–72.

Boeije H. A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality and Quantity. 2002;36(4):391–409.

Kolb SM. Grounded theory and the constant comparative method: valid research strategies for educators. J Emerg Trends Educ Res Pol Stud. 2012;3(1):83–6.

Jones G, Hughes J, Mahmoodi N, Smith E, Skull J, Ledger W. What factors hinder the decision-making process for women with cancer and contemplating fertility preservation treatment? Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23(4):433–57.

Quinn GP, Vadaparampil ST, King L, Miree CA, Wilson C, Raj O, et al. Impact of physicians’ personal discomfort and patient prognosis on discussion of fertility preservation with young cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(3):338–43.

Taylor JF, Ott MA. Fertility preservation after a cancer diagnosis: a systematic review of adolescents’, parents’, and providers’ perspectives, experiences, and preferences. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29(6):585–98.

Ussher JM, Parton C, Perz J. Need for information, honesty and respect: patient perspectives on health care professionals communication about cancer and fertility. Reprod Health. 2018;15:2.

Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65:s63–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) in addition to Lonnie Zeltzer, MD, Margaret Stuber, MD, Theodore Moore, MD, and the UCLA Pediatric Residency Training Program leadership and staff, especially Alan Chin, MD, James Lee, MD, Jasen Liu, MD, and Savanna Carson, PhD.

Funding

This study was funded by the Western Region of the Association of Pediatric Program Directors’ (W-APPD) Medical Education Research Grant (Award Number: #2017-106; Recipient: Lindsay F. Schwartz, MD) and the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR001881.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 23 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schwartz, L.F., Braddock, C.H., Kao, R.L. et al. Creation and evaluation of a cancer survivorship curriculum for pediatric resident physicians. J Cancer Surviv 12, 651–658 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0702-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0702-z