Abstract

Purpose

Longitudinal studies are needed to characterise the burden of second primary malignancies among cancer survivors. Therefore, we quantified the incidence rate and cumulative incidence of second primary cancers (SPC) and standardised incidence ratios (SIR) in a population-based cohort of subjects diagnosed with a first primary cancer (FPC).

Methods

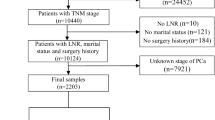

We evaluated a cohort of cancer patients from the Portuguese North Region Cancer Registry (RORENO), with the first diagnosis in 2000–2003 (n = 39451), to estimate the incidence rate and cumulative incidence of SPC and standardised incidence ratios (SIR), for different periods of follow-up, up to 5 years; SPC were defined according to the International Association of Cancer Registries and the International Agency for Research on Cancer guidelines.

Results

The incidence rate of SPC was more than 5-fold higher in the first 2 months of follow-up than in the period between 2 months and 5 years (metachronous SPC), across which the incidence rates were relatively stable. Cancer survivors had an overall higher incidence rate of cancer than the general population (SIR = 1.31 (95 % confidence interval (CI), 1.25–1.38)), although that difference faded when only metachronous SPC were considered (SIR = 1.02 (95 % CI, 0.96–1.08)). Cancer incidence rates were higher among female lung FPC survivors and lower in prostate FPC cancer survivors than in the general population. The 5-year cumulative risk of developing a metachronous SPC was 3.0 % and reached nearly 5.0 % among patients with FPC associated with lower risk of death.

Conclusions

Cancer survivors had higher incident rates of cancer that the general population, especially due to diagnoses in the first months following the FPC. Nevertheless, after this period SPC remain frequent events among cancer survivors.

Implications for cancer survivors

SPC constitute an important dimension of the burden of cancer survivorship, and this needs to be taken into account when defining strategies for surveillance, prevention and counselling.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Araujo F, et al. Trends in cardiovascular diseases and cancer mortality in 45 countries from five continents (1980–2010). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013.

De Angelis R et al. Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE-5—a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(1):23–34.

Ferlay J et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, cancer incidence and mortality worldwide. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013.

Pacheco-Figueiredo L, Lunet N. Health status, use of healthcare, and socio-economic implications of cancer survivorship in Portugal: results from the Fourth National Health Survey. J Cancer Surviv. 2014.

Curtis R, et al. New malignancies among cancer survivors: SEER cancer registries, 1973–2000. National Cancer Institute; NIH Publ., 2006. No. 05-5302.

Travis LB. The epidemiology of second primary cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(11):2020–6.

Rosso S et al. Multiple tumours in survival estimates. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(6):1080–94.

Pacheco-Figueiredo L et al. Evaluation of the frequency of and survival from second primary cancers in North Portugal: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2013;22(6):599–606.

International rules for multiple primary cancers (ICD-0 third edition). Eur J Cancer Prev, 2005; 14(4):307–8.

Howe HL. A review of the definition for multiple primary cancers in the United States. Springfield: North American Association of Central Cancer Registries; 2003.

RORENO. Registo Oncologico Regional do Norte. IPO - Porto. 2006.

Teppo L, Pukkala E, Saxen E. Multiple cancer—an epidemiologic exercise in Finland. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75(2):207–17.

Youlden DR, Baade PD. The relative risk of second primary cancers in Queensland, Australia: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:83.

Jegu J et al. The effect of patient characteristics on second primary cancer risk in France. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:94.

Tabuchi T et al. Incidence of metachronous second primary cancers in Osaka, Japan: update of analyses using population-based cancer registry data. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(6):1111–20.

Storm HH et al. Multiple primary cancers in Denmark 1943–80; influence of possible underreporting and suggested risk factors. Yale J Biol Med. 1986;59(5):547–59.

Coleman MP. Multiple primary malignant neoplasms in England and Wales, 1971–1981. Yale J Biol Med. 1986;59(5):517–31.

Crocetti E, Buiatti E, Falini P. Multiple primary cancer incidence in Italy. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(18):2449–56.

Liu L et al. Prevalence of multiple malignancies in the Netherlands in 2007. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(7):1659–67.

Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG, Bojesen SE. Associations between first and second primary cancers: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2012;184(1):E57–69.

Morrison A. Screening in chronic disease. New York: Oxford University Press; 1985.

Cancer trends progress report–2011/2012 update. National Cancer Institute, NIH Publ., 2012.

Corkum M et al. Screening for new primary cancers in cancer survivors compared to non-cancer controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):455–63.

Pacheco-Figueiredo L et al. Health-related behaviours in the EpiPorto study: cancer survivors versus participants with no cancer history. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2011;20(4):348–54.

Rundle A et al. A prospective study of socioeconomic status, prostate cancer screening and incidence among men at high risk for prostate cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(2):297–303.

Morgan RM et al. Socioeconomic variation and prostate specific antigen testing in the community: a United Kingdom based population study. J Urol. 2013;190(4):1207–12.

Henderson BE, Feigelson HS. Hormonal carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(3):427–33.

Thompson D, Easton DF. Cancer incidence in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(18):1358–65.

Mavaddat N et al. Cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from prospective analysis of EMBRACE. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(11):812–22.

Dourado F, Carreira H, Lunet N. Mammography use for breast cancer screening in Portugal: results from the 2005/2006 National Health Survey. Eur J Pub Health. 2013;23(3):386–92.

Shafer D, Albain K. Lung cancer outcomes in women. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(6):532–41.

Alves L, Bastos J, Lunet N. Trends in lung cancer mortality in Portugal (1955–2005). Rev Port Pneumol. 2009;15(4):575–87.

Carreira H et al. Trends in the prevalence of smoking in Portugal: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:958.

Castro C et al. Assessing the completeness of cancer registration using suboptimal death certificate information. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21(5):478–9.

Travis LB et al. Aetiology, genetics and prevention of secondary neoplasms in adult cancer survivors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(5):289–301.

Acknowledgements

Luís Pacheco-Figueiredo received a grant from the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (SFRH/SINTD/60124/2009).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pacheco-Figueiredo, L., Antunes, L., Bento, M.J. et al. Incidence of second primary cancers in North Portugal—a population-based study. J Cancer Surviv 10, 142–152 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0460-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0460-0