Abstract

Purpose

Large, population-based studies are needed to better understand lymphedema, a major source of morbidity among breast cancer survivors. One challenge is identifying lymphedema in a consistent fashion. We sought to develop and validate an algorithm using Medicare claims to identify lymphedema after breast cancer surgery.

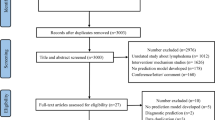

Methods

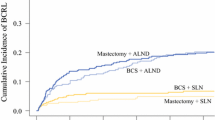

From a population-based cohort of 2,597 elderly (65+) women who underwent incident breast cancer surgery in 2003 and completed annual telephone surveys through 2008, two algorithms were developed using Medicare claims from half of the cohort and validated in the remaining half. A lymphedema-positive case was defined by patient report.

Results

A simple two ICD-9 code algorithm had 69 % sensitivity, 96 % specificity, positive predictive value >75 % if prevalence of lymphedema is >16 %, negative predictive value >90 %, and area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.82 (95 % CI 0.80–0.85). A more sophisticated, multi-step algorithm utilizing diagnostic and treatment codes, logistic regression methods, and a reclassification step performed similarly to the two-code algorithm.

Conclusions

Given the similar performance of the two validated algorithms, the ease of implementing the simple algorithm and the fact that the simple algorithm does not include treatment codes, we recommend that this two-code algorithm be validated in and applied to other population-based breast cancer cohorts.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

This validated lymphedema algorithm will facilitate the conduct of large, population-based studies in key areas (incidence rates, risk factors, prevention measures, treatment, and cost/economic analyses) that are critical to advancing our understanding and management of this challenging and debilitating chronic disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Efron B. How biased is the apparent error rate of a prediction rule? J Am Stat Assoc. 1986;81:461–70.

Cooper GS, Virnig B, Klabunde CN, Schussler N, Freeman J, Warren JL. Use of SEER-Medicare data for measuring cancer surgery. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-43-8.

McClish DK, Penberthy L, Whittemore M, Newschaffer C, Woolard D, Desch CE, et al. Ability of Medicare claims data and cancer registries to identify cancer cases and treatment. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:227–33.

Rector TS, Wickstrom SL, Shah M, Thomas Greeenlee N, Rheault P, Rogowski J, et al. Specificity and sensitivity of claims-based algorithms for identifying members of Medicare + Choice health plans that have chronic medical conditions. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1839–57. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00321.x.

Molinaro AM, Simon R, Pfeiffer RM. Prediction error estimation: a comparison of resampling methods. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(15):3301–7. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti499.

Nattinger AB, Laud PW, Bajorunaite R, Sparapani RA, Freeman JL. An algorithm for the use of Medicare claims data to identify women with incident breast cancer. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1733–49.

Freeman JL, Zhang D, Freeman DH, Goodwin JS. An approach to identifying incident breast cancer cases using Medicare claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:605–14.

Warren JL, Feuer E, Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lynch CF. Use of Medicare hospital and physician data to assess breast cancer incidence. Med Care. 1999;37:445–56.

Ramsey SD, Scoggins JF, Blough DK, McDermott CL, Reyes CM. Sensitivity of administrative claims to identify incident cases of lung cancer: a comparison of 3 health plans. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15:659–68.

Goldberg DS, Lewis JD, Halpern SD, Weiner MG, Lo Re 3rd V. Validation of a coding algorithm to identify patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in an administrative database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:103–7. doi:10.1002/pds.3367.

Hassett MJ, Ritzwoller DP, Taback N, Carroll N, Cronin AM, Ting GV, et al. Validating billing/encounter codes as indicators of lung, colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer recurrence using 2 large contemporary cohorts. Med Care. 2012. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318277eb6f.

Chubak J, Yu O, Pocobelli G, Lamerato L, Webster J, Prout MN, et al. Administrative data algorithms to identify second breast cancer events following early-stage invasive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:931–40. doi:10.1093/jnci/djs233.

Lamont EB, Herndon 2nd JE, Weeks JC, Henderson IC, Earle CC, Schilsky RL, et al. Measuring disease-free survival and cancer relapse using Medicare claims from CALGB breast cancer trial participants (companion to 9344). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1335–8. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj363.

McClish D, Penberthy L, Pugh A. Using Medicare claims to identify second primary cancers and recurrences in order to supplement a cancer registry. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:760–7.

Earle CC, Nattinger AB, Potosky AL, Lang K, Mallick R, Berger M, et al. Identifying cancer relapse using SEER-Medicare data. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-75-81.

Allen LA, Yood MU, Wagner EH, Aiello Bowles EJ, Pardee R, Wellman R, et al. Performance of claims-based algorithms for identifying heart failure and cardiomyopathy among patients diagnosed with breast cancer. Med Care. 2014;52:e30–8. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31825a8c22.

Sewell JM, Rao A, Elliott SP. Validating a claims-based method for assessing severe rectal and urinary adverse effects of radiotherapy. Urology. 2013;82:335–40. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2013.02.071.

Petrek JA, Pressman PI, Smith RA. Lymphedema: current issues in research and management. CA Cancer J Clin. 2000;50:292–307. quiz 8–11.

Sparaco A, Fentiman IS. 9. Arm lymphoedema following breast cancer treatment. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56:107–10.

Hayes SC, Johansson K, Stout NL, Prosnitz R, Armer JM, Gabram S, et al. Upper-body morbidity after breast cancer: incidence and evidence for evaluation, prevention, and management within a prospective surveillance model of care. Cancer. 2012;118(8 Suppl):2237–49. doi:10.1002/cncr.27467.

Maunsell E, Brisson J, Deschenes L. Arm problems and psychological distress after surgery for breast cancer. Can J Surg. 1993;36:315–20.

Fu MR, Ridner SH, Hu SH, Stewart BR, Cormier JN, Armer JM. Psychosocial impact of lymphedema: a systematic review of literature from 2004 to 2011. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1466–84. doi:10.1002/pon.3201.

Shih YC, Xu Y, Cormier JN, Giordano S, Ridner SH, Buchholz TA, et al. Incidence, treatment costs, and complications of lymphedema after breast cancer among women of working age: a 2-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2007–14. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.18.3517.

Disipio T, Rye S, Newman B, Hayes S. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:500–15. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70076-7.

Erickson VS, Pearson ML, Ganz PA, Adams J, Kahn KL. Arm edema in breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:96–111.

Petrek JA, Heelan MC. Incidence of breast carcinoma-related lymphedema. Cancer. 1998;83(12 Suppl American):2776–81.

Armer JM, Stewart BR. Post-breast cancer lymphedema: incidence increases from 12 to 30 to 60 months. Lymphology. 2010;43:118–27.

McLaughlin SA. Lymphedema: separating fact from fiction. Oncology. 2012;26:242–9.

Reiner AS, Jacks LM, Van Zee KJ, Panageas KS. A SEER-Medicare population-based study of lymphedema-related claims incidence following breast cancer in men. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:301–6. doi:10.1007/s10549-011-1649-1.

Kwan ML, Darbinian J, Schmitz KH, Citron R, Partee P, Kutner SE, et al. Risk factors for lymphedema in a prospective breast cancer survivorship study: the Pathways Study. Arch Surg. 2010;145:1055–63. doi:10.1001/archsurg.2010.231.

From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in translation. 1 ed. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2005.

Nattinger AB, Pezzin LE, Sparapani RA, Neuner JM, King TK, Laud PW. Heightened attention to medical privacy: challenges for unbiased sample recruitment and a possible solution. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:637–44. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq220.

Yen TW, Fan X, Sparapani R, Laud PW, Walker AP, Nattinger AB. A contemporary, population-based study of lymphedema risk factors in older women with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:979–88. doi:10.1245/s10434-009-0347-2.

The North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, Inc. http://www.naaccr.org. Accessed 17 Feb 2014.

ICD-9 CM International classification of diseases, 9th revision. Millenium edition. 2008. Los Angeles: Practice Management Information Corporation; 2007.

Current Procedural Terminology: CPT 2004. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2003.

HCPCS Health Care Financing Administration Common Procedure Coding System. National Level II Medicare Codes. Millennium edition. 2008. Los Angeles: Practice Management Information Corporation; 2007.

Kwan W, Jackson J, Weir LM, Dingee C, McGregor G, Olivotto IA. Chronic arm morbidity after curative breast cancer treatment: prevalence and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4242–8.

Altman DG, Bland JM. Diagnostic tests 2: predictive values. BMJ. 1994;309:102.

HIPAASpace. Medical Data Services. Healthcare Lookup Services. HCPCS Lookup. http://www.hipaaspace.com/Medical_Billing/Coding/Healthcare_Common_Procedure_Coding_System/HCPCS_Codes_Lookup.aspx. Accessed 17 Feb 2014.

HCPCSdata.com. 2006 HCPCS L Codes. http://www.hcpcsdata.com/2006/L/default.htm. Accessed 17 Feb 2014.

International Society of Lymphology. The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema. 2009 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology. 2009;42:51–60.

Koul R, Dufan T, Russell C, Guenther W, Nugent Z, Sun X, et al. Efficacy of complete decongestive therapy and manual lymphatic drainage on treatment-related lymphedema in breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:841–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.09.024.

Sayko O, Pezzin LE, Yen TW, Nattinger AB. Diagnosis and treatment of lymphedema after breast cancer: a population-based study. PMR. 2013;5(11):915–23. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.05.005.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a career development award and supplement to Dr. Yen from the National Cancer Institute (K07CA125586, K07CA125586-03S1) and two research grants from the National Cancer Institute to Dr. Nattinger (R01CA81379, R01CA127648). The content does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest

All authors (Tina Yen, Purushuttom Laud, Rodney Sparapani, Jianing Li, and Ann Nattinger) declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Integrity of research and reporting

This study was approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin’s institutional review board. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yen, T.W.F., Laud, P.W., Sparapani, R.A. et al. An algorithm to identify the development of lymphedema after breast cancer treatment. J Cancer Surviv 9, 161–171 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-014-0393-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-014-0393-z