Abstract

Building on prior work examining discrete emotions and consumer behavior, the present research proposes that consumers are more likely to engage in the target sustainable behavior when marketers use an emotional appeal that matches the brand’s expressed values or one that is congruent with consumers’ value priority. In particular, we focus on two contrasting positive emotions—pride and awe. We show that the effectiveness of pride and awe appeals depends on the corresponding human values. Specifically, pride increases sustainable behavior and intentions when the self-enhancement value is prioritized; and awe increases sustainable behavior and intentions when the self-transcendence value is prioritized. Importantly, this interaction can be explained by enhanced self-efficacy. We demonstrate these effects across six studies, including a field study. Our findings contribute to a better understanding of sustainable consumption, reconcile prior research, and provide practical guidance for marketers and policy-makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Increasing awareness of the importance of sustainability has led many firms to adopt green tactics in their communications that seek to influence consumer behavior (Newman et al., 2014; Olson, 2013; Sheth et al., 2011; Sipilä et al., 2021). For example, Gong Cha, a famous bubble tea brand, used the pride appeal in their advertisement (i.e., “I am pro-environmental, I am proud of myself”)Footnote 1 to encourage consumers to buy sustainable accessories (e.g., reusable cloth bags and green cups). Similarly, C’est bon, a well-established Chinese beverage brand, used images of Chinese Olympic athletes on their product packaging (i.e., “We are Team China”) that could potentially elicit nationalistic pride among Chinese consumers (see Web Appendix A). Moreover, in collaboration with the World Wide Fund for Nature, the One Planet Foundation launched the “Pride on our Plates”Footnote 2 campaign to reduce food waste. Thus, it begs the question, to what extent can the pride appeal increase the sales of Gong Cha’s green products, promote consumers’ recycling behavior of C’est bon’s disposable plastic bottle after consumption, or reduce food waste in China?

Surprisingly, the literature is equivocal on the effect of pride on sustainable behavior. While some researchers show that pride positively predicts intentions to protect the environment (e.g., Antonetti & Maklan, 2014; Schneider et al., 2017), others suggest that pride does not affect ethical decision-making (Piff et al., 2015), and may even reduce e-WOM intentions for sustainable brands (Septianto et al., 2021). Thus, more research is needed to understand how and when pride can consistently promote sustainable behavior. To this end, the present research proposes and shows that the effectiveness of the pride-based appeal depends on the values consumers endorse or those that the brand communicates.

Emotion is a powerful tool that marketers can use to influence consumer behavior (Andrade, 2015; Cavanaugh et al., 2015; Rees et al., 2015). While there is an established stream of research investigating the effects of negative emotions on sustainable consumer behavior (e.g., sadness, guilt and shame; Rees et al., 2015; Schwartz & Loewenstein, 2017), there is also increasing recognition that positive emotions are promising interventions to enhance sustainable behavior (Peter & Honea, 2012; Wang et al., 2017; White et al., 2019; Winterich et al., 2019). Among the most frequently experienced positive emotions in daily life (e.g., joy, pride, awe, contentment, love, compassion, and amusement; Shiota et al., 2006), pride and awe represent two distinct emotions that could differentially promote sustainable behavior.

While pride has received mixed findings in the literature, as noted above, awe has been identified as a promising emotional antecedent to sustainable behavior, but its effects and mechanism have not been empirically examined (White et al., 2019). Anecdotal evidence from BBC’s Blue Planet documentary suggests that the feeling of awe in nature may influence sustainable behavior (Feay, 2017). The well-known outdoor apparel brand Patagonia often uses awe-inspiring images of nature on its website and in its ads (see Web Appendix A). Nonetheless, it has been noted that some awe-inspiring natural attractions (e.g., Mt. Everest and Phi Phi Islands in Thailand) are highly polluted with human waste (BBC news, 2016). Thus, it is not clear when and how awe would influence sustainable behavior (White et al., 2019).

The limited prior research on awe has focused on prosocial behavior, such as generosity and helping behavior toward other people (Piff et al., 2015; Prade & Saroglou, 2016). The literature recognizes important nuanced distinctions between prosocial behavior and sustainable behavior (Yan et al., 2021a). For example, while prosocial behavior benefits other individuals (Batson & Powell, 2003), sustainable behavior benefits the environment itself and its human inhabitants (Callicott, 1995). Moreover, prior research suggests that prosocial (e.g., charitable giving and helping behavior) and sustainable behaviors (e.g., green purchase and recycling) can have different predictors, thus they merit separate investigations (Cavanaugh et al., 2015; Goenka & Van Osselaer, 2019; Olson, 2013; Schneider et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2021a). In summary, pride and awe are different positive emotions frequently experienced by individuals and also often used by marketers. However, there is a lack of understanding on their efficacy and underlying psychological mechanisms. Insight into the differential effects of pride and awe can help marketers and policy-makers to develop more targeted and effective campaigns promoting sustainable behavior. By contrasting the influence of pride and awe, the present research aims to yield novel insights on their distinct effects on sustainable behavior beyond general positivity (Piff et al., 2015).

According to the appraisal-tendency framework (Han et al., 2007), emotions are defined by unique sets of appraisal dimensions that describe their core relational themes and form coherent appraisal processes through which events are interpreted. These unique appraisals differentiate one emotion from another (Ellsworth & Scherer, 2003; Keltner & Horberg, 2015). In this vein, pride is similar to awe in that both are positive and arousing emotions, but they differ in their value appraisals (Campos et al., 2013; Keltner & Haidt, 2003). Specifically, pride has the core relational theme of feeling personal accomplishment, while awe has the core relational theme of feeling small relative to others (Campos et al., 2013). Differences in their appraisal dimensions can lead to varying effects of pride and awe on human behavior (Piff et al., 2015). A recent meta-analysis shows that gratitude, love, and pride have varying effects on product evaluation and purchase behavior (Kranzbühler et al., 2020). Thus, untangling the unique effects of discrete emotions on specific sustainable behaviors can help marketers to develop more targeted interventions (Cavanaugh et al., 2015; Coleman et al., 2020; Septianto et al., 2021).

We also know, however, that consumer decision-making is not only affected by feelings but also guided by values at the moment of decision-making (e.g., Goenka & Van Osselaer, 2019). Human values are among the most influential factors guiding daily life (Schwartz, 1992) and brands can be perceived as representations of human values (Torelli et al., 2012). In practice, marketers imbue brands or marketing messages with certain values, such as Rolex with self-enhancement (i.e., power, status, and influence), and the Red Cross with self-transcendence (i.e., universalism and benevolence) (Rodas et al., 2021). Consumers often favor brands that align with their dominant human values (Shepherd et al., 2015; Torelli et al., 2012). Importantly, consumers’ value priorities can affect how they interpret emotional experiences (Tamir et al., 2016), and their decision-making often depends on the salient appraisal dimension of the emotions (Briñol et al., 2018). Thus, we propose that the interplay between discrete emotions and salient values can significantly influence consumers’ decision-making.

In this vein, recent research suggests that discrete emotions can be differentiated based on human values (Stellar et al., 2017), and that emotions can prioritize an individual’s sensitivity to certain values (Haidt, 2003). Given that pride is linked to the self-enhancement value appraisal and awe is linked to the self-transcendence value appraisal (Stellar et al., 2017; Tamir et al., 2016), we propose that pride promotes sustainable behavior when self-enhancement is prioritized, while awe promotes sustainable behavior when self-transcendence is prioritized. In the following sections, we will further explain how congruence between discrete positive emotions and human values increases consumers’ perceived self-efficacy (i.e., one’s confidence and capability to execute the target task; Bandura, 1986), which promotes sustainable behavior. We will elaborate on these predictions in the hypothesis development section below.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. We first review the relevant literature on discrete positive emotions (focusing on pride and awe) and human values (focusing on self-enhancement and self-transcendence), as well as their interactions, in the context of sustainable behavior. Following that, we explain the mediating role of self-efficacy. We then conduct six empirical studies, followed by a general discussion of the key findings, theoretical contributions, managerial implications, and future research directions.

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Sustainable behavior and discrete emotions

Sustainable or pro-environmental behavior refers to consumers’ actions that lower adverse environmental impacts and decrease utilization of natural resources across the lifecycle of the product, behavior, or service (White et al., 2019). There are various forms of sustainable behavior, such as signing up for or participating in pro-environmental activities (Rees et al., 2015), choosing or buying green products (Griskevicius, Tybur, & Van den Bergh, 2010b; Yan et al., 2021a; Yan et al., 2021b), conserving resources (Bissing-Olson et al., 2016; Goldstein et al., 2008), donating to pro-environmental causes (Harth et al., 2013), as well as recycling and proper disposal (Karmarkar & Bollinger, 2015; Kidwell et al., 2013). As noted earlier, notwithstanding the overlap between prosocial behavior and sustainable behavior (Paramita et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2021a), the recipients of these behaviors differ; the former benefits other people while the latter benefits both the environment and its inhabitants (Nolan & Schultz, 2015). Thus, the same emotion (i.e., pride) could have varying effects on donating money versus engaging in sustainable behavior (Schneider et al., 2017). Moreover, distinct positive emotions do not universally increase prosocial behavior but, instead, encourage different forms of prosocial behavior (Cavanaugh et al., 2015).

There is an extensive literature on the effects of emotions on consumer behavior (for a review, see Andrade, 2015), including sustainable behavior. While earlier research tends to focus on the role of negative emotions on sustainable behavior (e.g., guilt and sadness; Rees et al., 2015; Schwartz & Loewenstein, 2017), more recent research recognizes the relevance of positive emotions in this domain (e.g., pride, inspiration, and cuteness; Septianto et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2017; Winterich et al., 2019). Notably, distinct positive emotions exert differential effects on message persuasion (Karsh & Eyal, 2015) and vary in their effects on specific behaviors (Schneider et al., 2017). There is increasing recognition that positive emotions should be studied discretely, each with its own elicitors, action tendencies, and subsequent cognitive and behavioral outcomes (Piff et al., 2015; Prade & Saroglou, 2016; So et al., 2015). Web Appendix B provides an illustrative summary of prior research on the effects of pride, awe, and other relevant discrete emotions in the domains of sustainable behavior and prosocial behavior. For the reasons explained earlier, the present research focuses on the contrasting emotions of pride and awe and their effects on sustainable behavior.

Pride

Pride is what we feel after a valued achievement, such as doing well on a difficult exam or getting a deserved promotion (Griskevicius et al., 2010a). Pride is a self-conscious emotion (Lerner & Keltner, 2000), such that it tends to enhance one’s sense of the self, promote feelings of self-worth, social status, personal success, and propel further achievements (Cheng et al., 2010; Tracy & Robins, 2007). Prior research identifies two forms of pride—authentic and hubristic. Authentic pride reflects feeling proud of an accomplishment, whereas hubristic pride is associated with feeling proud of the global self or being arrogant (Tracy & Robins, 2007). The present research focuses on authentic pride. Earlier research on the effects of pride is equivocal, yet intriguing (e.g., Antonetti & Maklan, 2014; Bissing-Olson et al., 2016; Onwezen et al., 2013; Schneider et al., 2017; see Web Appendix B). More recent research suggests that the effect of pride is contingent on contextual cues. For example, pride increases the purchase of luxury brands, but not of sustainable brands (Septianto et al., 2021). Moreover, pride appeals in cause-related marketing are effective only for individuals with a promotion regulatory focus (Coleman et al., 2020). Thus, the present research identifies human values as an important boundary condition for the effect of pride on sustainable behavior, which is new to the literature.

Awe

In contrast to pride, awe is an other-oriented emotion (Keltner & Haidt, 2003). Awe is a sense of wonder we feel in the presence of something vast that transcends the individual self (Piff et al., 2015). Distinct from other positive emotions, awe is elicited by perceptually vast stimuli that surpass one’s current frame of reference (Keltner & Haidt, 2003). The feeling of awe is linked to perceived vastness and a need to accommodate a new scheme (Bai et al., 2017; Piff et al., 2015). In particular, experiencing awe can lead to a sense of the “small self” (Piff et al., 2015), foster feelings of connection (Shiota et al., 2007), and increase collective engagement (Bai et al., 2017), thus promoting generosity toward other people (Prade & Saroglou, 2016; Stellar et al., 2017). While prior research has examined the effects of awe on prosocial behavior (Piff et al., 2015), there is little research on how awe influences sustainable behavior (White et al., 2019). In addition, the effects of awe can be moderated by individual differences (e.g., agreeableness; Prade & Saroglou, 2016) and cultural variations (Bai et al., 2017). Thus, examining how and when awe could promote sustainable behavior extends our understanding on the scope and boundaries of the prosocial effects of awe (Piff et al., 2015). Moreover, the present research provides practical insights and suggestions for marketers on how to use awe appeals effectively by considering brand values and consumers’ value priorities.

The interaction effects of pride, awe, and human values

The appraisal-tendency framework (ATF, Han et al., 2007; Lerner & Keltner, 2000) is widely used to study the effects of specific emotions on judgment and decision-making. This approach defines an emotion by a unique set of central appraisal dimensions that describe its core meaning (Ellsworth & Scherer, 2003; Lerner & Keltner, 2000). For example, Smith and Ellsworth (1985) identify six cognitive dimensions underlying different emotions—certainty, pleasantness, attentional activity, control, anticipated effort, and responsibility. Subsequent research examines other appraisal dimensions such self-other agency (e.g., pride vs. gratitude; Agrawal et al., 2013), approach and avoidance tendencies (e.g., calmness vs. sadness; Labroo & Rucker, 2010), self-other similarity (e.g., pride vs. compassion; Oveis et al., 2010), and temporal focus (e.g., pride vs. happiness vs. hopefulness; Winterich & Haws, 2011), all of which could shape consumer behavior and decision-making.

The ATF suggests that a discrete emotion may share some common appraisals with another emotion, but would differ on other appraisal dimensions (So et al., 2015). The unique appraisals associated with each emotion activate a cognitive tendency that leads individuals to evaluate the subsequent event in a consistent manner (Lerner & Keltner, 2000). For example, gratitude has the unique value appraisal of care, while compassion has the unique value appraisal of fairness. Thus, when consumers experience the feeling of gratitude versus compassion, they would respond more favorably to the donation request from a charitable organization that emphasizes the moral objective of care versus fairness, respectively (Goenka & Van Osselaer, 2019). Other congruity effects have been found for the self-other agency appraisal of anger and shame on information processing (Agrawal et al., 2013), as well as the temporal focus appraisal of excitement and calm on product choice (Mogilner et al., 2012). In essence, this stream of research suggests that congruence between the distinct appraisal dimension of emotions and the target objectives can enhance domain-specific effects (Horberg et al., 2011).

By extension, the present research proposes congruity effects between human values and the discrete emotions of pride and awe on sustainable behavior. Human values refer to desirable goals, varying in importance, that serve as guiding principles in people’s lives (Schwartz, 1992). Schwartz’s (1992) human values model has ten conceptually distinct values, each associated with a particular abstract goal representing motivations for goals. These values can be mapped along two bipolar dimensions with four higher values—self-transcendence in opposition to self-enhancement (i.e., the ST/SE dimension), and openness to change in opposition to conservation (Schwartz et al., 2012). The present research focuses on the ST/SE dimension, which reflects a conflict between concern for the welfare of others and pursuit of personal interests (Schwartz, 1992), compatible with awe (i.e., other-oriented) and pride (i.e., self-oriented).

Specifically, the ST value emphasizes diminished self-importance and increased attention to others, reflecting a motivation to transcend selfish concerns and promote collective benefits (Schwartz et al., 2012), including sub-values such as responsibility, helpfulness, environmental protection, and care (Burson et al., 2012; Schwartz & Boehnke, 2004). In contrast, the SE value emphasizes power and influence, reflecting a motivation to enhance the self and promote personal benefits (Schwartz et al., 2012), including sub-values such as power, success, status, capability, and influence (Burson et al., 2012; Schwartz & Boehnke, 2004).

As pride arises from the perceived self’s accomplishments and rising social status (Tracy & Robins, 2007), it emphasizes self-superiority and self-benefits, which are reflective of the SE value (Cheng et al., 2010). In contrast, awe arises from the perceived virtue of others (Keltner & Haidt, 2003); thus, it emphasizes transcending the self for others, which is reflective of the ST value (Haidt, 2003). Accordingly, we propose that congruence between pride and the SE value, as well as between awe and the ST value would increase propensity for the desired sustainable behavior. This prediction is consistent with prior research showing that affirmation of values important to the self leads to more sustainable behavior (Brough et al., 2016; Sparks et al., 2010). More formally, we hypothesize that:

H1

There is an interaction effect between discrete positive emotions and human values such that:

-

(a)

pride increases sustainable behavior when the SE value is prioritized;

-

(b)

awe increases sustainable behavior when the ST value is prioritized;

-

(c)

when the SE value is salient, pride has a stronger effect than awe on sustainable behavior;

-

(d)

when the ST value is salient, awe has a stronger effect than pride on sustainable behavior.

Mediating role of perceived self-efficacy

We further propose that the congruity effects of discrete positive emotions and human values on sustainable behavior can be explained by perceived self-efficacy. Perceived self-efficacy refers to individuals’ belief in their “capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to attain designated types of performances” (Bandura, 1986, p. 391). It reflects consumers’ belief or confidence that they can perform particular acts and carry out the behavior to have the intended impact (Bandura, 1997). In our context, self-efficacy refers to consumers’ confidence in their capability to perform sustainable behavior that contributes to a better environment.

Prior research suggests that perceived self-efficacy can function as an important determinant of self-regulation by influencing the amount of effort that individuals invest in a task and how long they persist when confronted with obstacles (Mukhopadhyay & Johar, 2005). In particular, perceived self-efficacy has been found to positively predict consumers’ sustainable attitudes and their tendencies to continue to enact sustainable behaviors over time (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Schutte & Bhullar, 2017; White et al., 2011). For instance, White et al. (2011) show that congruence between message frame (i.e., gain or loss) and construal level (i.e., abstract or concrete) can increase ease of processing fluency, resulting in greater perceived self-efficacy and higher recycling intentions. Moreover, congruence between consumers’ value orientation and affective state can increase confidence in their product choice evaluations (Adaval, 2001). Similarly, we propose that congruence between discrete positive emotions and human values can increase sustainable behavior by enhancing perceived self-efficacy.

Prior research has indicated that endorsing self-enhancement is associated with feeling pride, while endorsing self-transcendence is associated with feeling awe (Tamir et al., 2016). Therefore, we predict that when a value is paired with a congruent emotion—for example, self-enhancement with pride or self-transcendence with awe—the consumer “feels right” about what they are doing or going to do (Camacho et al., 2003; Kruglanski, 2006). We contend that feeling right is an engaging experience that increases the consumer’s perceived self-efficacy to execute the target behavior (Higgins, 2006; Kruglanski, 2006). In this way, emotion‒value congruence strengthens the consumer’s belief that they can execute sustainable behavior and that their behavior makes a difference to the environment. This is consistent with prior research showing that a higher self-efficacy can result in greater recycling intentions and behaviors (Schutte & Bhullar, 2017; White et al., 2011). More formally, we hypothesize that:

H2

Congruence between discrete positive emotions and human values enhances perceived self-efficacy, which in turn promotes sustainable behavior.

The present research

We tested our hypotheses in six studies using different marketing scenarios and stimuli. First, Study 1a established the congruity effect of pride and SE on recycling intention in contrast to a neutral condition (H1a). Using a similar design, Study 1b showed the congruity effect of awe and ST on intentions to reuse a towel in a hotel (H1b). Study 1c tested the relative effects of pride and awe on recycling behavior (H1c and H1d). Study 2 examined the emotion‒value interaction effect on participation in a plastic-free campaign in a field setting (H1c and H1d). Study 3 tested this effect on a green purchase behavior and used a more practical method to prime brand values (H1c and H1d). Study 4 confirmed the interaction effect on a different green purchase behavior and also supported the mediating role of enhanced self-efficacy (H2).

We listed the experimental stimuli for all studies in the Appendix and additional priming details in Web Appendix C. We reported the manipulation check and pretest results in Web Appendix D. The key measurement items are shown in Web Appendix E. We reported the full ANOVA, ANCOVA, and additional analyses in Web Appendix F. We provided details of the Study 4 mediation results in Web Appendix G.

Moreover, to understand how pride and awe increase self-efficacy when their congruent value is salient, we explore the differential effects of pride and awe on two facets of meaning in life (i.e., search for meaning and presence of meaning; Steger et al., 2006) and subsequently on self-efficacy and sustainable behavioral intentions. We propose that pride enhances self-efficacy via search for meaning while awe enhances self-efficacy via presence of meaning when their congruent value is salient, both of which increase sustainable behavioral intentions. In so doing, we tease out their unique effects in the process. Details on the hypothesis development and empirical results are shown in Web Appendix H.

Study 1 Baseline effects of pride and awe

Study 1a: Baseline effect of pride

Study 1a aimed to establish the baseline effect of pride in contrast to a neutral condition. To increase the practical implications of the study, we primed emotions and values using messages in posters for recycling. We expect that pride increases recycling intention when the SE value is salient, and this positive effect is driven by the congruence between pride and SE rather than the incongruence between pride and ST that reduced recycling intention compared to the baseline.

Design and procedure

Study 1a (https://aspredicted.org/3MS_WSP) was a preregistered study using a 2 (emotion: pride vs. neutral) × 2 (value: ST vs. SE) between-participants design. The dependent variable was recycling intention. We recruited 420 U.S. participants on the Prolific platform with nominal payment. Forty participants who failed the instructional attention checks or completed the task too quickly were excluded (Oppenheimer et al., 2009), leaving 380 valid responses (52.37% female, Mage = 35.63).

Participants were instructed to imagine that their community was launching a recycling program and they were randomly assigned to see one of four posters that varied in their expressions of values and emotions. Specifically, we used the words “have the responsibility,” “help protect the environment,” and “preserve nature” to prime the ST value, and the words “have the choice,” “make an impact for a better self,” and “influence the outcome” to prime the SE value. Similarly, we used the slogans “feel proud to recycle” to prime pride, and “please recycle” for the neutral condition (see the Appendix). Following that, participants indicated their recycling intentions on a 7-point Likert scale (“How likely / how inclined / how willing are you to recycle; M = 4.85, SD = 1.54, α = 0.95; Web Appendix E). Across all studies, we used 7-point Likert scales for all measures, and we used the same items unless otherwise specified.

We also administered manipulation check questions at the end. Participants reported their feelings on happiness, pride, and several other emotions. They also indicated to what extent the poster expressed the SE value (being powerful / being impactful / being influential; M = 4.49, SD = 1.42, α = 0.77) and the ST value (being responsible / being helpful / being supportive; M = 5.38, SD = 1.36, α = 0.86). As ST and SE are two opposing values along the same continuum (Schwartz, 1992), we created a value priority index by subtracting the SE score from the ST score (M = 0.89, SD = 1.27), with a higher score denoting a ST value priority (Burson et al., 2012). We reported the manipulation check results using individual scores and the difference score in Web Appendix D.

Recycling intention

A 2 × 2 ANOVA on recycling intention showed only a significant interaction effect of emotion × value (F(1, 376) = 4.40, p = 0.037, ƞp2 = 0.012). Decomposing the interaction effect (Fig. 1a), planned contrasts showed that pride led to higher recycling intention compared to the neutral state in the SE condition (Mpride = 5.28, SD = 1.30 vs. Mneutral = 4.68, SD = 1.62; F(1, 376) = 7.19, p = 0.008, ƞp2 = 0.019), but not significantly different from the neutral state in the ST condition (Mpride = 4.70, SD = 1.67 vs. Mneutral = 4.76, SD = 1.44; p = 0.79). Viewed another way, pride led to higher recycling intention when the SE value was prioritized than when the ST value was prioritized (MSE = 5.28 vs. MST = 4.70; F(1, 376) = 6.62, p = 0.01, ƞp2 = 0.017), but there was no significant difference between the SE and ST values in the neutral state (MSE = 4.68 vs. MST = 4.76; p = 0.71). These results indicated that pride only increased sustainable behavior when the SE value was prioritized, supporting H1a.

Study 1b: Baseline effect of awe

Similarly, we conducted Study 1b to establish the baseline effect of awe in contrast to a neutral condition. To increase the practical implications, we tested the effect in a tourism context. We primed emotions using ads for a fictitious ski resort (Rudd et al., 2018) and then created two prompts for towel reuse in the room (Goldstein et al., 2008). We expect that the feeling of awe will increase towel reuse intention when the ST value is salient in the prompt.

Design and procedure

Study 1b used a 2 (emotion: awe vs. neutral) × 2 (value: ST vs. SE) between-participants design. The dependent variable was intention to reuse the towel in the room. We recruited 420 U.S. participants on the Prolific platform with nominal payment. Thirty-four participants who failed the instructional attention checks were excluded, leaving 386 valid responses (55.18% female, Mage = 35.44) for the final analysis.

Following Rudd et al. (2018), we created two versions of ads about a fictitious ski resort—STRYKX, which were similar except for the images (see the Appendix). We used the same images from Rudd et al. (2018) for the awe condition (i.e., a snowy mountain peak) and the neutral condition (i.e., ski equipment at the resort). We then created two prompts varying in expressed values (see the Appendix). Specifically, we used the words “make a responsible choice,” “help protect,” “support,” and “save the planet” to prime the ST value, and the words “make an impactful choice,” “power,” “influence,” and “for a better self” to prime the SE value.

Participants were asked to imagine that that they were on a winter vacation at the STRYKX Ski Resort (Rudd et al., 2018), and were randomly assigned to see one of the two ads promoting the resort. Following that, they reported their feelings toward the ski resort on eight specific emotions (e.g., awe, happiness) as a manipulation check. They were then randomly assigned to see one of the two prompts for towel reuse in the bathroom, and were asked to rate their likelihood to reuse the towel during their stay at the resort (“How likely / how inclined / how willing are you to reuse the same towel?” M = 6.15, SD = 1.21, α = 0.95). Finally, as a manipulation check of values, participants indicated the extent to which the prompt message reflected the SE value (M = 4.50, SD = 1.42, α = 0.76) and the ST value (M = 5.82, SD = 1.23, α = 0.88) using the same items as in Study 1a. We reported the manipulation checks results for this study in Web Appendix D.

Towel reuse intention

A 2 × 2 ANOVA on towel reuse intention showed only a significant interaction effect of emotion × value (F(1, 382) = 6.96, p = 0.009, ƞp2 = 0.018). Planned contrasts showed that awe led to higher reuse intention than the neutral state in the ST condition (Mawe = 6.44, SD = 0.75 vs. Mneutral = 5.96, SD = 1.29; F(1, 382) = 7.41, p = 0.007, ƞp2 = 0.019), but not significantly different from the neutral state in the SE condition (Mawe = 6.01, SD = 1.61 vs. Mneutral = 6.18, SD = 1.02; F < 1, p = 0.32) (Fig. 1b). Viewed another way, awe led to higher reuse intention when the ST value was salient than when the SE value was salient (MST = 6.44 vs. MSE = 6.01; F(1, 382) = 6.23, p = 0.013, ƞp2 = 0.016), but the effect disappeared in the neutral state (MST = 5.96 vs. MSE = 6.18; F(1, 382) = 1.54, p = 0.21). These results indicated that awe (vs. baseline) only increased sustainable behavior when the ST value was prioritized, supporting H1b.

Study 1c: Relative effects of awe and pride

Studies 1a and 1b showed the congruity effects of pride and awe with the SE value and the ST value, respectively, against a neutral condition. Nonetheless, the results did not differentiate the effects of pride and awe from general emotional positivity. That is, priming pride and awe also increased general emotional positivity compared to the neutral state; thus, it is unclear whether it is the positivity of the emotions that contributed to the effect or the discrete emotion itself or both. To tease out the unique effects of pride and awe beyond general positivity, we tested the relative effects of awe and pride on recycling behavior in Study 1c.

Design and procedure

Study 1c (https://aspredicted.org/VFJ_N1Y) was a preregistered study using a 2 (emotion: awe vs. pride) × 2 (value: ST vs. SE) between-participants design. The dependent variable was recycling intention. We recruited 560 U.S. participants on the Prolific platform with nominal payment. Seventy responses that failed the instructional attention checks were excluded, leaving 490 responses (56.33% female, Mage = 35.96) for the final analysis.

Similar to Study 1a, we created four similar posters for recycling varying in expressed values and emotions (see the Appendix). We used the slogans “feel proud to recycle” and “feel proud of yourself” to prime pride, and “feel awed to recycle” and “feel in awe of nature” to prime awe. We conducted a pretest (N = 275, 69.09% female) to validate the manipulations of emotions and values in the four posters before the main study (Web Appendix D).

As in Study 1a, participants were randomly assigned to see one of the four posters, and then indicated their recycling intentions (“How likely / how inclined / how willing; M = 4.89, SD = 1.45, α = 0.92), followed by their demographics.

Recycling intention

A 2 × 2 ANOVA on recycling intention showed only a significant interaction effect of emotion × value (F(1, 486) = 20.43, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.040). Decomposing the interaction effect (Fig. 1c), planned contrasts showed that pride led to significantly higher recycling intention than awe in the SE condition (Mpride = 5.17, SD = 1.32 vs. Mawe = 4.43, SD = 1.55; F(1, 486) = 17.15, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.034); conversely, awe led to higher recycling intention than pride in the ST condition (Mawe = 5.21, SD = 1.21 vs. Mpride = 4.78, SD = 1.56; F(1, 486) = 5.22, p = 0.023, ƞp2 = 0.011). These results supported H1c and H1d.

Viewed another way, pride led to higher recycling intention in the SE condition than in the ST condition (MSE = 5.17 vs. MST = 4.78; F(1, 486) = 4.48, p = 0.035, ƞp2 = 0.009); conversely, awe led to higher recycling intention in the ST condition than in the SE condition (MST = 5.21 vs. MSE = 4.43; F(1, 486) = 18.27, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.036).

Discussion

Studies 1a and 1b showed that discrete emotions (i.e., pride and awe) and human values jointly drove sustainable behavior, compared to a neutral state as baseline. Study 1c further showed that the relative efficacies of pride and awe depended on their congruent values, such that pride increased sustainable behavior when the SE value was salient, while awe increased sustainable behavior when the ST value was salient. Notably, these effects were not confounded with general emotional positivity. Taken together, human values play an important moderating role on the efficacy of pride and awe appeals on sustainable behavior, supporting H1.

Study 2: Actual sign-up behavior

Study 2 aimed to further test the interaction effects between discrete positive emotions and human values in a field experiment. We conducted this study at a large university in China.

Design and procedure

Study 2 used a 3 (emotion: awe vs. pride vs. elevation)Footnote 3 × 2 (value: ST vs. SE) between-participants design. The dependent variable was an actual pledge (sign-up) for a plastic-free campaign. We first created six versions of web posters that encouraged students to participate in a plastic-free campaign. The six conditions varied in the target emotion (i.e., awe, pride, and elevation) and human value (i.e., ST and SE) using different combinations of images and slogans. Specifically, we used the words “responsible” and “help” to prime the ST value, and “be able to” and “make an impact” to prime the SE value. For example, in the awe and ST condition, the activity was promoted using the slogan “Feeling Awed to Go Green! You are responsible to help protect the environment,” accompanied by an awe-inspiring image of the main building on campus; while in the awe and SE condition, it was promoted as “Feeling Awed to Go Green! You are able to make an impact on the environment” accompanied by the same image. For the pride condition (“Feeling Proud to Go Green!”), we used a generic image depicting student graduation that typically elicits the feeling of pride.Footnote 4 As all participants were senior-year students who would be graduating soon, the graduation image should be effective in eliciting their anticipated pride. The poster was designed as a web-based slide. The slide was followed by a pledge letter for the plastic-free campaign and a QR code to sign-up for this activity (Web Appendix C). A pretest (N = 105) was conducted to validate the effectiveness of the posters before the main study, and the details are reported in Web Appendix D.

In the main study, we selected six classes of the same course on campus, and each class was assigned to see one of the six web posters. We hired a representative from the student union as our research assistant to communicate this plastic-free campaign to each class leader, who then sent details of the web poster about the upcoming campaign to students in their own class using a link in WeChat (each class had a separate WeChat group).

The poster indicated that the plastic-free campaign was an activity initiated by the student union in conjunction with the university’s Better Campus Campaign, which aimed to promote pro-environmental habits such as improving hygiene, reducing food waste, and increasing recycling behavior. The notification function on WeChat enabled us to record the number of students who actually read the campaign message. Participants first saw the image together with a slogan on the cover page, followed by the pledge letter on the following page. Those interested in signing up for the plastic-free campaign were instructed to scan the QR code to register their name and class information. In total, 300 students (49.33% female, Mage = 19.80) read the message, and 127 students scanned the QR code and registered their names, resulting in 42.33% actual sign-ups.

Results and discussion

Sign-up for plastic-free campaign

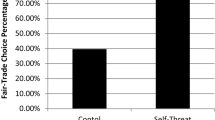

We conducted a binary logistic regression using actual sign-up as the dependent variable (sign-up = 1, not sign-up = 0), and emotion, human value, and their interaction terms as predictors. Results showed a significant effect of human value (B = -0.54, Wald = 6.72, p = 0.01, Exp(B) = 0.58) and a significant interaction effect of emotion × human value (B = 1.10, Wald = 13.52, p < 0.001, Exp(B) = 3.02). Decomposing the interaction effect, awe led to more sign-ups when paired with the ST value than with the SE value (52.1% vs. 26.5%, B = 0.57, Wald = 6.81, p = 0.009, Exp(B) = 1.76), whereas pride led to led to more sign-ups when paired with the SE value than with the ST value (55.8% vs. 30.0%, B = -0.54, Wald = 6.72, p = 0.01, Exp(B) = 0.58). Viewed another way, in the ST condition, awe led to more sign-ups (52.1%) compared to pride (30.0%, B = -0.93, Wald = 4.85, p = 0.028, Exp(B) = 0.39). Conversely, in the SE condition, pride led to more sign-ups (55.8%) compared to awe (26.5%, B = 1.28, Wald = 8.98, p = 0.003, Exp(B) = 3.59), supporting H1c and H1d.

Discussion

Conducted in a field setting, Study 2 showed that there were more sign-ups for the plastic-free campaign when awe was paired with the ST value, and when pride was paired with the SE value, consistent with the preceding studies. While Study 2 provided external validity for the findings, a limitation was that different stimuli (images and slogans) were used to prime the emotions and human values, which were not easily comparable. Nonetheless, showing a generic graduation image without indicating specific affiliation of the university offered a conservative test for pride. In the following Studies 3 and 4, we conducted controlled experiments to enhance the internal validity and also extend the application of the findings to other sustainable behaviors.

Study 3: Green purchase intentions

Study 3 aimed to test the interaction effect of emotions and values on purchase intention for a green product, which is another form of sustainable behavior. In this study, we primed values in brand positioning to increase the practical implications of our findings.

Method

Design and participants

Study 3 (https://aspredicted.org/6TS_RF5) was a preregistered study using a 2 (emotion: awe vs. pride) × 2 (brand value: ST vs. SE) between-participants design. The dependent variable was purchase intention for green sports shoes. In total, we recruited 450 U.S. participants on the Prolific platform with nominal payment. Forty-eight participants who failed the attention check questions or completed the survey too quickly were dropped, and we had 402 valid responses (52.49% female, Mage = 35.00) for the final analysis.

Procedure and stimuli

We created four product ads for a fictitious brand XYZ that were similar except for the expressed values and emotions (see the Appendix). Specifically, we used the words of “be proud of your choice” and “wear with a sense of pride” to prime pride, and “be awed by your choice” and “wear with a sense of awe” to prime awe. The awe conditions also had blue sky and mountain peaks in the background to enhance the feeling of awe. We primed SE value by stating that the new eco-friendly product “conveys status, prestige and an exquisite taste in fashion” and “enhance your sports experience for a greater self.” Similarly, we primed ST value by stating that the new product “expresses responsibility and caring for the environment” and “transcend your personal interests for a better planet.”

To enhance SE value priming, before seeing the posters, participants read that “Brand XYZ shifts its focus toward making premium products” and described the new eco-friendly sports shoes as “a unique and prestigious product” with “an exquisite design to signal status” and “for a better customer experience.” To enhance ST value priming, participants read that “Brand XYZ shifts its focus toward making sustainable products” and described the new eco-friendly sports shoes as “available to everyone who wants to help protect the environment,” “considering society’s welfare” and “for a better environment.”

Before the main study, we conducted a pretest (N = 196, 68.88% female) to validate the effectiveness of the four posters in terms of values and emotions priming (Web Appendix D). The results indicated that the values and emotions were manipulated successfully as expected.

In the main study, participants were randomly assigned to see one of the four ads promoting the new green sports shoes. After reading the ad, participants indicated their purchase intentions for the green sports shoes (“How likely / how inclined / how willing;” M = 4.68, SD = 1.39, α = 0.94). We also measured likability of the ad (“To what extent do you like this ad?” 1 = not at all, 7 = very much, M = 4.63, SD = 1.50) as a covariate.

Results and Discussion

Purchase intention

A 2 (emotion) × 2 (brand value) ANOVA on purchase intention for the green sports shoes revealed a significant interaction effect (F(1, 398) = 31.56, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.073) and a significant main effect of brand value (F(1, 398) = 4.19, p = 0.041, ƞp2 = 0.010). The main effect of emotion was nonsignificant (F(1, 398) = 1.95, p = 0.163, ƞp2 = 0.005). An ANCOVA with ad likability as a covariate still showed a significant interaction effect (F(1, 397) = 23.84, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.057).

Decomposing the interaction effect (Fig. 2), planned contrasts showed that pride led to higher purchase intention than awe in the SE condition (Mpride = 5.02, SD = 1.26 vs. Mawe = 4.09, SD = 1.57; F(1, 398) = 24.95, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.059), supporting H1c. Conversely, awe led to higher purchase intention than pride in the ST condition (Mawe = 5.11, SD = 1.09 vs. Mpride = 4.55, SD = 1.33; F(1, 398) = 8.79, p = 0.003, ƞp2 = 0.022), supporting H1d. Viewed another way, pride led to higher purchase intention when paired with the SE value than with the ST value (5.02 vs. 4.55; F(1, 398) = 32.92, p = 0.014, ƞp2 = 0.015), while awe led to higher purchase intention when paired with the ST value than with the SE value (5.11 vs. 4.09; F(1, 398) = 30.76, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.072).

Discussion

Study 3 further confirmed that the pride appeal was more effective than the awe appeal when the brand expressed SE value (H1c). In contrast, the awe appeal was more effective than the pride appeal when the brand expressed ST value (H1d), consistent with the preceding studies. In other words, the awe appeal was more effective when paired with the ST value, while the pride appeal was more effective when paired with the SE value. In the next study, we tested the underlying mechanism of perceived self-efficacy.

Study 4: Mediating role of perceived self-efficacy

Study 4 aimed to test the mediating role of perceived self-efficacy (H2), and to replicate the interaction effect (H1) using participants from a different country. Separately, prior research shows that processing fluency serves as the mechanism underlying the congruity effect (Labroo & Lee, 2006; Lee et al., 2010). In particular, Kidwell et al. (2013) find that message congruence enhances processing fluency, which increases recycling intentions. In addition, White et al. (2011) find that congruence between message frame and construal level increases processing fluency, which further enhances consumer efficacy, and subsequently increases recycling intentions. Thus, we measured processing fluency as an alternative explanation. Moreover, as our theoretical development on the underlying mechanism of perceived self-efficacy assumed the reinforcing effect of the feeling of engagement (Granziera & Perera, 2019), we also measured the feeling of engagement to confirm this assumption.

Method

Design and participants

Study 4 used a 3 (emotion: awe vs. elevation vs. pride)Footnote 5 × 2 (ad value: ST vs. SE) between-participants design. The dependent variable was purchase intention for a green backpack. We recruited 500 U.K. participants on the Prolific platform with nominal payment. We dropped twenty participants who failed the attention check questions, leaving 480 responses (68.96% female, Mage = 39.98) for the final analysis.

Emotion induction

We first primed awe, elevation, and pride by asking participants to recall an experience of the target emotion and to write the experience in some detail (Griskevicius et al., 2010a; Piff et al., 2015). To ensure that participants had the same understanding about the specific emotion, we provided a definition of the target emotion in the instruction (Web Appendix C). We also gave examples to facilitate the recall task. For instance, in the awe condition, participants read, “When experiencing awe, people usually feel like they are in the presence of something that is so great in terms of size or intensity … This might have been a breathtaking view from a high place, or a vast and overwhelming commercial image that you felt was breathtaking.” After the writing task, participants rated the extent to which they felt a set of emotions—happiness, amusement, awe, elevation, pride, anger, fear, sadness, and guilt—for a manipulation check (Piff et al., 2015).

Procedure and stimuli

Following that, participants were directed to a shopping scenario for a backpack made using recycled materials. They were randomly assigned to see one of two ads (see the Appendix). The ST ad promoted the green backpack by using the words, “transcend your own personal interests for a better world,” “you can make a socially responsible purchase by buying this backpack,” and “promote the welfare of others;” while the SE ad promoted the green backpack by using the words, “enhance your own personal outcomes for a better self,” “you can make a statement about yourself by buying this backpack,” and “convey your status, prestige and exquisite taste.” Then participants indicated their purchase intention for the backpack (M = 4.93, SD = 1.27, α = 0.92; Web Appendix E).

Following that, we measured perceived self-efficacy using four items from Keller (2006; M = 4.65, SD = 1.26, α = 0.92; Web Appendix E). We measured the feeling of engagement (M = 4.62, SD = 1.30, r = 0.72) and processing fluency (M = 5.55, SD = 1.39, α = 0.95) using the items from Lee et al. (2010). In addition, we measured moral identity for an exploratory purpose.

As a manipulation check for human values, participants indicated the extent to which the ad message reflected the SE value (M = 3.92, SD = 1.86, α = 0.92) and the ST value (M = 5.32, SD = 1.49, α = 0.92). Finally, they reported their positive affect (M = 4.64, SD = 1.07, α = 0.92), negative affect (M = 1.62, SD = 0.89, α = 0.94) on the 20-item PANAS scale (Watson et al., 1988) as relevant covariates, followed by their demographics.

Results and discussion

Purchase intention

A 3 (emotion) × 2 (value) ANOVA on purchase intention for the green backpack revealed a significant interaction effect (F(2, 474) = 8.75, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.036) and a marginally significant main effect of value (F(1, 474) = 3.40, p = 0.066, ƞp2 = 0.007). The main effect of emotion was nonsignificant (F < 1, p = 0.89). An ANCOVA including positive affect and negative affect as covariates still showed a significant interaction effect of emotion × value (F(2, 472) = 7.97, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.033) on purchase intention.

Decomposing the interaction effect (Fig. 3), the results revealed that awe led to higher purchase intention for the ST ad than for the SE ad (MST = 5.15, SD = 1.23 vs. MSE = 4.62, SD = 1.29; F(1, 474) = 7.01, p = 0.008, ƞp2 = 0.015). Conversely, pride led to higher purchase intention for the SE ad than for the ST ad (MSE = 5.18, SD = 1.04 vs. MST = 4.72, SD = 1.29; F(1, 474) = 5.55, p = 0.019, ƞp2 = 0.012). Viewed another way, the effect of emotion was significant in both the ST (F(2, 474) = 4.06, p = 0.018, ƞp2 = 0.017) and SE conditions (F(2, 474) = 4.81, p = 0.009, ƞp2 = 0.020). That is, awe led to higher purchase intention than pride for the ST ad (t(239) = 2.20, p = 0.029), while pride led to higher purchase intention than awe for the SE ad (t(235) = -2.81, p = 0.005).

Perceived self-efficacy

A 3 × 2 ANOVA on perceived self-efficacy revealed only a significant interaction effect of emotion × value (F(2, 474) = 7.28, p = 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.030). Planned contrasts showed that awe led to higher perceived self-efficacy for the ST ad than for the SE ad (MST = 4.88, SD = 1.30 vs. MSE = 4.45, SD = 1.17; F(1, 474) = 4.66, p = 0.031, ƞp2 = 0.010). Conversely, pride led to higher perceived self-efficacy for the SE ad than for the ST ad (MSE = 4.90, SD = 0.99 vs. MST = 4.39, SD = 1.52; F(1, 474) = 6.64, p = 0.01, ƞp2 = 0.014).

Mediating role of perceived self-efficacy

A moderated mediation analysis with self-efficacy as the mediator and emotion (three levels) as a categorical independent variable (Model 8, Hayes, 2018) showed significant moderated mediation effects for both D1 (pride vs. awe: index = 0.55, 95% CI = [0.221, 0.895]) and D2 (pride vs. elevation: index = 0.08, 95% CI = [0.216, 0.886]). Conditional mediation effect analysis showed that, for the SE ad, pride led to higher perceived self-efficacy compared to awe, and subsequently increased recycling intention (b = -0.26, SE = 0.10, 95% CI = [-0.472, -0.064]). Conversely, for the ST ad, awe led to higher perceived self-efficacy compared to pride, and subsequently increased recycling intention (b = 0.28 SE = 0.13, 95% CI = [0.023, 0.551]). These results supported H2. Further details on the mediation results, including the results related to elevation and engagement are shown in Web Appendices F and G.

Processing fluency

A 3 × 2 ANOVA on processing fluency showed a significant interaction effect of emotion × value (F(2, 474) = 8.98, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.037). A moderated mediation analysis showed a significant mediation effect of processing fluency for the SE ad (D1: 95% CI = [-0.233, -0.012]; D2: 95% CI = [-0.270, -0.022]), but not for the ST ad (both D1 and D2 included zero). An additional parallel mediation with self-efficacy and processing fluency as mediators showed similar results. Thus, processing fluency could not fully explain the interaction effect.

Discussion

Study 4 provided evidence supporting the mediation effect of self-efficacy underlying the interaction between discrete positive emotions and human values on purchase intention for the green product (H2). Moreover, findings from the mediation analysis (Web Appendices F and G) on engagement and the relationship between engagement and processing fluency were consistent with prior research (Lee et al., 2010).

General discussion

In extending the literature on the interaction between emotion and cognition (Keltner & Horberg, 2015), the present research examines the interaction effects of discrete positive emotions and human values. Across six studies, we show that sustainable behavior can be promoted via congruence between self-transcendence and the emotions of awe (and elevation), as well as via congruence between self-enhancement and pride. Thus, the present research is the first to identify self-regulating values (i.e., self-transcendence and self-enhancement) as boundaries for the effectiveness of discrete positive emotions in promoting sustainable behaviors. In doing so, we help reconcile mixed findings in the extant literature. Furthermore, we reveal the role played by self-efficacy, which underlies the congruity effect on sustainable behavior. Practically, the results of this research shed light on how managers can utilize different positive emotions to improve the effectiveness of sustainability campaigns.

In addition, as noted earlier, we explored the differential effects of pride and awe on two facets of meaning in life and sustainable behavior when their congruent values are salient (Web Appendix H). We found that the relative effects of pride and awe on self-efficacy, as a function of human values, work through two separate facets of meaning in life—search for meaning and presence of meaning in life (Steger et al., 2006). The findings are new to the literature and have important implications for consumer well-being. In particular, we reveal the unique impact of pride on search for meaning, which is new to the literature (King & Hicks, 2021).

Theoretical contributions

First, our research contributes to an emerging literature seeking to identify factors promoting sustainable behavior (e.g., Winterich et al., 2019; Yan et al., 2021a, b). Specifically, we answer the call for more research to examine the role of discrete positive emotions on sustainable behavior (White et al., 2019). By examining pride and its congruence with the SE value, our results help reconcile prior equivocal findings on the effects of pride. For instance, while Onwezen et al. (2013) suggest that anticipated pride is as effective as anticipated guilt, Schneider et al. (2017) indicate that pride is more effective than guilt in sustainable decision-making. Yet other researchers reveal the negative effect of pride on sustainable brands (Septianto et al., 2021). By extension, we find that pride promotes sustainable behavior when paired with the SE value.

Moreover, by contrasting awe against pride, our findings enrich the scant literature on the effects of awe in marketing contexts (Kim et al., 2021; Rudd et al., 2018). While prior research has examined the effects of awe on prosocial behaviors (e.g., helping behavior, ethical decision-making, and generosity; Piff et al., 2015), White et al., (2019, p. 32) wrote that “to our knowledge no work looks at how awe impacts sustainable consumer behaviors.” Notably, we show that elevation, which shares the same value appraisal of the ST value with awe (Stellar et al., 2017), can also generate the same effect as awe on sustainable behavior (Web Appendix F), in contrast to pride.

Thus, it is not the case that one emotion is universally better at motivating all behaviors than other emotions (Cavanaugh et al., 2015; So et al., 2015). Rather, we show that it is only when the discrete positive emotion interacts with a congruent human value that it can positively influence sustainable behavior. Our approach is consistent with, yet distinct from, related research that examines congruence between other discrete positive emotions and values. Specifically, Goenka and Van Osselaer (2019) show that congruence between two other-oriented emotions (i.e., gratitude and compassion) and moral values (i.e., care and fairness) can promote prosocial behavior. We extend their findings by examining the unique effects of pride and awe on sustainable behavior, as well as their interactions with polar opposites of the value continuum—ST and SE values. Our work also differs from Kim and Johnson (2013) who study the congruity effect of a positive self-conscious emotion (i.e., pride) and a negative other-oriented emotion (i.e., guilt) with cultural values (independence vs. interdependence) on preference for cause-related options. Notably, our focal emotions of pride and awe have similar levels of valence and arousal.

Furthermore, the present research contributes to the literature on human values in consumer research. Prior research examining the effects of human values on sustainable behavior has yielded mixed results. For instance, while Steg et al. (2014) suggest that human values moderate the effects of pro-environmental goals on sustainable behavior, Thøgersen and Ölander (2002) reveal the direct effects of human values on sustainable behavior. Our approach focusing on the interactive effects of emotions and human values offers more nuanced insights, in line with prior research showing that cultural congruity and compatibility between human values influences consumers’ responses to global brands (Torelli et al., 2012). When the values signaled by a brand align with consumers’ dominant ideology, they respond more favorably to the value-congruent brand (Shepherd et al., 2015). We extend this line of research by showing the congruity effect between discrete positive emotions and human values on sustainable behavior.

Practical implications

As environmental issues become more acute, understanding and promoting sustainable consumer behavior take on greater importance. In practice, marketers need to have appropriate tools or tactics (e.g., emotional appeals, value framing) to promote specific consumer behaviors such as sustainable consumption (Cavanaugh et al., 2015; White et al., 2019). To this end, our research findings have direct implications for organizations and brands operating in the values domain by demonstrating how managers can utilize different positive emotions to improve the effectiveness of their sustainability campaigns. Through six studies incorporating various forms of sustainable behavior and practical stimuli, our findings offer insights and examples for how managers and policy makers can effectively tap into discrete positive emotions and values to achieve the desired consumer outcomes.

Specifically, our results help managers to identify discrete positive emotions that could promote sustainable consumer behavior, when coupled with the corresponding human values. For example, pro-environmental ad campaigns can prime positive emotions such as awe or pride by using images and slogans that match the ST or SE value, respectively. Conversely, for green brands and products expressing certain human values (Shepherd et al., 2015; Torelli et al., 2012), our findings suggest that they should adopt value-congruent emotions to target the corresponding market segments. For instance, prior research indicates that the different generation cohorts in the U.S. and China have varying value orientations (Egri & Ralston, 2004). Specifically, in the U.S., Generation X consumers attach higher importance to the SE value compared to the Baby Boomers and the Silent Generation; thus, using pride in advertising messages would be more effective at persuading Generation Xers compared to other generation cohorts. In China, the Republican generation attaches greater importance to the ST value compared to the Consolidation and Cultural Revolution cohorts; thus, using awe and elevation themed messages would be more effective in marketing to the Republican cohort.

Notably, consumers’ sustainable attitudes or intentions may not always translate into actual behaviors (White et al., 2019). To reduce the intention‒behavior gap, Fennis et al. (2011) suggest using persuasive appeals high in vividness to foster participants’ mental imagery that underlies the effectiveness of implementation intentions. Specifically, Fennis et al. (2011) suggest encouraging participants to visualize specific situations in which they might carry out the intended behavior (where, when, and how the goals are acted on) and to imagine doing so. Recent research shows that using the first-person (vs. third-person) perspective with an implementation mindset can enhance consumer engagement with the message (Zhang et al., 2022). Illustrative examples of practicable implementation intentions include:

-

When I dispose of my household waste, I will sort and put them in the corresponding bins;

-

When I dispose of used papers at work, I will always put them into the recycling bin;

-

When I shop for toilet paper, I will choose the product made from sustainable materials;

-

When I place food order online, I will avoid using disposable tableware;

-

When I stay at a hotel, I will reuse the same towel throughout my stay.

Limitations and future research

Although it is generally not necessary to demonstrate a strong connection between intentions and behaviors in every study reported in a paper (Hulland & Houston, 2021), a limitation of the current research is that our empirical studies relied heavily on intention, with only one study examining actual behavior. Thus, future research can incorporate implementation intentions (e.g., asking participants to visualize specific situations in which they might carry out the intended behavior) to strengthen the connection between intentions and behaviors (Fennis et al., 2011). Future research can also use more realistic and situation-specific stimuli to reduce the intention‒behavior gap (Hulland & Houston, 2021).

In addition, our review of the literature indicates that other discrete emotions can also affect sustainable behavior (Web Appendix B). Potentially, there could be emotions that have effects similar to the ones that we are studying—for example, other-oriented emotions such as empathy or gratitude may influence sustainable behavior in a manner comparable to awe. Our aim in this research, however, is not to test an exhaustive list of emotions that might influence sustainable behavior. Rather, our goal is to propose and test a parsimonious emotion‒value congruity framework on sustainable behavior. While the present research examines the congruity effects of three discrete positive emotions (i.e., awe, elevation, and pride) and human values (i.e., self-transcendence and self-enhancement) on sustainable behavior, future research can test our framework using other discrete positive emotions that share the same value appraisal with awe and elevation, such as gratitude, admiration, and love. Similarly, besides pride, there may be negative emotions, such as anger and disgust, which are congruent with the SE value. Thus, it would be useful to test the robustness of our framework using a wider set of discrete emotions.

Moreover, while the present research focuses on two groups of emotions that have ST (vs. SE) values as their core appraisal dimensions, future research could test other emotions that can be mapped along other value appraisal dimensions. In addition, while the present research examines a trio of relatively high-arousal positive emotions, future research could contrast emotions that vary in arousal. Potentially, arousal could moderate our emotion‒value congruity effect, which merits further examination. Future research can also explore other potential moderators. For example, the efficacy of emotional stimuli is likely to depend on their compatibility with culture (Achar et al., 2016). Members of an individualist (vs. collectivist) culture may be more persuaded by emotional appeals that are self-oriented (e.g., pride) rather than those that are other-oriented (e.g., empathy and peacefulness) (Aaker & Williams, 1998). Thus, testing our framework from a cross-cultural perspective could yield additional insights.

Finally, sustainable consumption such as green purchase may be stage-specific, and self-oriented and other-oriented motives have varying effects at different consumption stages (Mai et al., 2021). Thus, it would be worthwhile to test the predictive power of the emotion‒human value congruity framework across different consumption stages (i.e., the participation stage when consumers decide on whether to purchase green products, and the expenditure stage when consumers decide on how much to spend on green products). Doing so would further enhance our understanding of the attitude-behavior gap in sustainable consumption.

Notes

To enhance the robustness of the findings, we introduced a third emotion of elevation, which shares the value appraisal of ST similar to awe (Stellar et al., 2017). The supplementary results for elevation are shown in Web Appendix F.

For the elevation condition (“Feeling Uplifted to Go Green!”), we showed an image of the university motto and mascot emphasizing the virtues of moral behavior in society.

As in Study 2, we had a third condition of elevation, and the results are shown in Web Appendix F.

References

Aaker, J. L., & Williams, P. (1998). Empathy versus pride: The influence of emotional appeals across cultures. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(3), 241–261.

Achar, C., So, J., Agrawal, N., & Duhachek, A. (2016). What we feel and why we buy: The influence of emotions on consumer decision-making. Current Opinion in Psychology, 10, 166–170.

Adaval, R. (2001). Sometimes it just feels right: The differential weighting of affect-consistent and affect-inconsistent product information. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(1), 1–17.

Agrawal, N., Han, D., & Duhachek, A. (2013). Emotional agency appraisals influence responses to preference inconsistent information. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 120(1), 87–97.

Andrade, E. B. (2015). Consumer emotions. In M. I. Norton, D. D. Rucker, & C. Lamberton (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of consumer psychology (pp. 90–121). Cambridge University Press.

Antonetti, P., & Maklan, S. (2014). Feelings that make a difference: How guilt and pride convince consumers of the effectiveness of sustainable consumption choices. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(1), 117–134.

Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–499.

Bai, Y., Maruskin, L. A., Chen, S., Gordon, A. M., Stellar, J. E., McNeil, G. D., Peng, K., & Keltner, D. (2017). Awe, the diminished self, and collective engagement: Universals and cultural variations in the small self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(2), 185–209.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Batson, C. D., & Powell, A. A. (2003). Altruism and prosocial behavior. In T. Millon & M. J. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Personality and social psychology (pp. 463–484). Wiley.

BBC News. (2016). Paradise lost: World's most beautiful places under threat of tourism. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-36313139. Accessed 18 Jul 2022.

Bissing-Olson, M. J., Fielding, K. S., & Iyer, A. (2016). Experiences of pride, not guilt, predict pro-environmental behavior when pro-environmental descriptive norms are more positive. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 145–153.

Brough, A. R., Wilkie, J. E., Ma, J., Isaac, M. S., & Gal, D. (2016). Is eco-friendly unmanly? The green-feminine stereotype and its effect on sustainable consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(4), 567–582.

Burson, A., Crocker, J., & Mischkowski, D. (2012). Two types of value-affirmation: Implications for self-control following social exclusion. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(4), 510–516.

Callicott, J. B. (1995). Intrinsic value in nature: A metaethical analysis. Electronic Journal of Analytic Philosophy, 3(5), 1–8.

Camacho, C. J., Higgins, E. T., & Luger, L. (2003). Moral value transfer from regulatory fit: What feels right is right and what feels wrong is wrong. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 498–510.

Campos, B., Shiota, M. N., Keltner, D., Gonzaga, G. C., & Goetz, J. L. (2013). What is shared, what is different? Core relational themes and expressive displays of eight positive emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 27(1), 37–52.

Cavanaugh, L. A., Bettman, J. R., & Luce, M. F. (2015). Feeling love and doing more for distant others: Specific positive emotions differentially affect prosocial consumption. Journal of Marketing Research, 52(5), 657–673.

Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., & Henrich, J. (2010). Pride, personality, and the evolutionary foundations of human social status. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(5), 334–347.

Coleman, J. T., Royne, M. B., & Pounders, K. R. (2020). Pride, guilt, and self-regulation in cause-related marketing advertisements. Journal of Advertising, 49(1), 34–60.

Egri, C. P., & Ralston, D. A. (2004). Generation cohorts and personal values: A comparison of China and the United States. Organization Science, 15(2), 210–220.

Ellsworth, P. C., & Scherer, K. R. (2003). Appraisal processes in emotion. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 572–595). Oxford University Press.

Feay, S. (2017). Blue Planet II, BBC 1 — awe-inspiring. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/90381c4e-baab-11e7-8c12-5661783e5589. Accessed 20 Jul 2022.

Fennis, B. M., Adriaanse, M. A., Stroebe, W., & Pol, B. (2011). Bridging the intention–behavior gap: Inducing implementation intentions through persuasive appeals. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(3), 302–311.

Goenka, S., & Van Osselaer, S. M. (2019). Charities can increase the effectiveness of donation appeals by using a morally congruent positive emotion. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(4), 774–790.

Goldstein, N. J., Cialdini, R. B., & Griskevicius, V. (2008). A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3), 472–482.

Granziera, H., & Perera, H. N. (2019). Relations among teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, engagement, and work satisfaction: A social cognitive view. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 58, 75–84.

Griskevicius, V., Shiota, M. N., & Nowlis, S. M. (2010a). The many shades of rose-colored glasses: An evolutionary approach to the influence of different positive emotions. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 238–250.

Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J. M., & Van den Bergh, B. (2010b). Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(3), 392–404.

Haidt, J. (2003). Elevation and the positive psychology of morality. In C. L. M. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 275–289). American Psychological Association.

Han, S., Lerner, J. S., & Keltner, D. (2007). Feelings and consumer decision making: The appraisal-tendency framework. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(3), 158–168.

Harth, N. S., Leach, C. W., & Kessler, T. (2013). Guilt, anger, and pride about in-group environmental behavior: Different emotions predict distinct intentions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 34(June), 18–26.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford.

Higgins, E. T. (2006). Value from hedonic experience and engagement. Psychological Review, 113(3), 439–460.

Horberg, E. J., Oveis, C., & Keltner, D. (2011). Emotions as moral amplifiers: An appraisal tendency approach to the influences of distinct emotions upon moral judgment. Emotion Review, 3(3), 237–244.

Hulland, J., & Houston, M. (2021). The importance of behavioral outcomes. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49(3), 437–440.

Karmarkar, U. R., & Bollinger, B. (2015). BYOB: How bringing your own shopping bags leads to treating yourself and the environment. Journal of Marketing, 79(4), 1–15.

Karsh, N., & Eyal, T. (2015). How the consideration of positive emotions influences persuasion: The differential effect of pride versus joy. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 28(1), 27–35.

Keller, P. A. (2006). Regulatory focus and efficacy of health messages. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(1), 109–114.

Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (2003). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 17(2), 297–314.

Keltner, D., & Horberg, E. J. (2015). Emotion-cognition interactions. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, E. Borgida, & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology, attitudes and social cognition (Vol. 1, pp. 623–664). American Psychological Association.

Kidwell, B., Farmer, A., & Hardesty, D. M. (2013). Getting liberals and conservatives to go green: Political ideology and congruent appeals. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(2), 350–367.

Kim, J. E., & Johnson, K. K. (2013). The impact of moral emotions on cause-related marketing campaigns: A cross-cultural examination. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(1), 79–90.

Kim, J., Bang, H., & Campbell, W. K. (2021). Brand awe: A key concept for understanding consumer response to luxury and premium brands. Journal of Social Psychology, 161(2), 245–260.

King, L. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2021). The science of meaning in life. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 561–584.

Kranzbühler, A. M., Zerres, A., Kleijnen, M. H., & Verlegh, P. W. (2020). Beyond valence: A meta-analysis of discrete emotions in firm-customer encounters. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(3), 478–498.

Kruglanski, A. W. (2006). The nature of fit and the origins of “feeling right”: A goal-systemic perspective. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(1), 11–14.

Labroo, A. A., & Lee, A. Y. (2006). Between two brands: A goal fluency account of brand evaluation. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(3), 374–385.

Labroo, A. A., & Rucker, D. D. (2010). The orientation-matching hypothesis: An emotion-specificity approach to affect regulation. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(5), 955–966.

Lee, A. Y., Keller, P. A., & Sternthal, B. (2010). Value from regulatory construal fit: The persuasive impact of fit between consumer goals and message concreteness. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(5), 735–747.

Lerner, J. S., & Keltner, D. (2000). Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion-specific influences on judgement and choice. Cognition and Emotion, 14(4), 473–493.

Mai, R., Hoffmann, S., & Balderjahn, I. (2021). When drivers become inhibitors of organic consumption: The need for a multistage view. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49, 1151–1174.

Mogilner, C., Aaker, J., & Kamvar, S. D. (2012). How happiness affects choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(2), 429–443.

Mukhopadhyay, A., & Johar, G. V. (2005). Where there is a will, is there a way? Effects of lay theories of self-control on setting and keeping resolutions. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 779–786.

Newman, G. E., Gorlin, M., & Dhar, R. (2014). When going green backfires: How firm intentions shape the evaluation of socially beneficial product enhancements. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(3), 823–839.

Nolan, J. M., & Schultz, P. (2015). Prosocial behavior and environmental action. In D. A. Schroeder & W. G. Graziano (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of prosocial behavior (pp. 626–652). Oxford University Press.

Olson, E. L. (2013). It’s not easy being green: The effects of attribute tradeoffs on green product preference and choice. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(2), 171–184.

Onwezen, M. C., Antonides, G., & Bartels, J. (2013). The norm activation model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology, 39(December), 141–153.

Oppenheimer, D. M., Meyvis, T., & Davidenko, N. (2009). Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 867–872.

Oveis, C., Horberg, E. J., & Keltner, D. (2010). Compassion, pride, and social intuitions of self-other similarity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(4), 618–630.

Paramita, W., Septianto, F., & Tjiptono, F. (2020). The distinct effects of gratitude and pride on donation choice and amount. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53, 101972.

Peter, P. C., & Honea, H. (2012). Targeting social messages with emotions of change: The call for optimism. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 31(2), 269–283.