Abstract

Scholarship at the intersection of transaction cost economics (TCE) and marketing has enjoyed an impressive record of growth over the past three decades, and the future promises more of the same. Following Erin Anderson’s perceptive uses of TCE in her 1982 dissertation, the field of marketing has made many constructive uses of and contributions to TCE, where the latter include broadening the reach of TCE, posing important challenges, and identifying opportunities still to be addressed. Given this history, we advance the proposition that the relation between TCE and marketing has been and should be a two-way street. In considering the scope for future research, we give special attention to issues of asymmetric costs, the dynamics of governance, and disequilibrium contracting. We also discuss the four precepts of pragmatic methodology, with special emphasis on prediction and empirical testing. The Appendix provides added perspective on the evolving “science of organization” of which TCE is a part.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We see merit in this distinction but refer to TCE throughout. In fact, although TCA is mainly based on TCE reasoning, it also appeals to agency theory. For some purposes, TCE and agency theory are complementary constructions.

Because Tarek Ghani did not have the pleasure of meeting Erin Anderson, the use of the first person singular pronoun in this section refers to Williamson.

Ouchi wrote a very favorable book review of Markets and Hierarchies (1975) for the Administrative Science Quarterly (1977). He and I had many occasions to share ideas in the years since.

Kenneth Arrow related to me that the reason he remembered me as one of his students is that I “asked good questions” in a course that I took from him when I was an MBA student at Stanford. Arrow further observed that asking good questions is how he came to the attention of his teachers when he was a PhD student at Columbia.

Empirical tests of transactions cost economics numbered over 900 in 2006 and have been broadly corroborative (Macher and Richman 2008). Indeed, “despite what almost 30 years ago may have appeared to be insurmountable obstacles to acquiring the relevant data [which are often primary data of a microanalytic kind], today transaction cost economics stands on a remarkably broad empirical foundation” (Geyskens et al. 2006, p. 531). There is no gainsaying that transaction cost economics has been much more influential because of the empirical work that it has engendered (Whinston 2001).

Erin Anderson “published 43 scholarly articles as well as six book chapters on transaction costs in action, and was nominated in ISI’s top 0.5% most cited scholars in business and economics in 2003” (A. Gatignon and H. Gatignon 2010, p. 232).

See Rindfleisch and Heide (1997, p. 30) for a detailed list of references corresponding to each of these five categories.

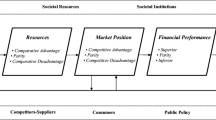

It is noteworthy how closely S-A-M processes replicate the “Commons Triple” of conflict, mutuality, and order. For one example of a marketing textbook that makes productive use of TCE, see Coughlan et al. (2006), particularly chapters 8, 9, and 13.

Interestingly, many of the early uses of TCE in marketing were done by PhD students working on their dissertations. Some have been heard to say (with a wink) that TCE is “young people’s economics.”

The performance evaluation problem, as framed by Rindfleisch and Heide (1997, p. 45), “arises when a firm whose decision-makers are limited by bounded rationality has difficulty assessing the contractual compliance of its exchange partners.”

Some marketing scholars are keen to move beyond the baseline setup and address new challenges. Others appear to believe that the basic model is unduly simple and/or over constraining. Although we applaud efforts to move beyond the basic setup, we believe that TCE is foundational and take the occasion here to set out the rudiments.

This discussion of pragmatic methodology is based on Williamson (2009, pp. 145–157).

Personal communications from Milton Friedman to Oliver Williamson, February 6, 2006.

One significant example of an inter-temporal regularity is the Fundamental Transformation, whereby what was a large numbers supply relation at the outset is transformed into a bilateral exchange relation thereafter by reason of investments in durable, specific assets that cannot be easily redeployed. Bureaucratization is another manifestation of an important but poorly understood inter-temporal regularity.

See “Transaction Cost Economics: The Precursors” (Williamson 2008).

See “Transaction Cost Economics and the Carnegie Connection” (Williamson 1996b).

See “The Economics of Governance” (Williamson 2005).

See “Economics and Antitrust Enforcement: The Transition Years” (Williamson 2003).

The Head of the Antitrust Division in 1968 is quoted as follows: “I approach customer and territorial restrictions not hospitably in the common law tradition, but inhospitably in the tradition of antitrust.” See Stanley Robinson, 1968, N.Y. State Bar Association, Antitrust Symposium, p. 29. Also see Coase (1972, p. 67).

Choice of the intermediate product market has the advantage that complications in contracts between firms and households (where differential information is important) and contracts between firms and labor (where differential risk aversion is important) can be set aside.

For example, debt and equity are not merely financial instruments but are also governance instruments (Williamson 1988).

I had earlier written to Ronald Coase to congratulate him for an especially interesting issue of the Journal of Law and Economics, to which Coase graciously responded by encouraging me to submit a paper to the JLE. I did not follow up until 1978, when I submitted “Transaction Cost Economics: The Governance of Contractual Relations” and included in my cover letter a mention of his earlier suggestion.

As it turned out, Coase was on leave when I submitted the paper. His co-editor informed me that he would hold the paper for Coase’s return but advised that the paper was “overwritten.” Coase evidently thought otherwise and asked only that I clarify what I meant by governance structure—to which I responded that a governance structure is “the institutional framework within which the integrity of a transaction is decided” (1979, p. 98).

The response to this article, by marketing scholars and others, has mainly been favorable: the paper is widely cited and has been reprinted 16 times. Although I am confident that I could have published it elsewhere, I am pleased that is was published in the JLE under Coase’s editorial auspices.

For a list of others who participated in the development of TCE, see the main text, including footnote 8.

References

Anderson, E. M. (1982). Contracting the selling function: The salesperson as outside agent or employee. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, United States.

Anderson, E. M. (1985). The salesperson as outside agent or employee: a transaction cost analysis. Marketing Science, 4, 234–254.

Anderson, E. M. (1988a). Transaction costs as determinants of opportunism in integrated and independent sales forces. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 9, 247–264.

Anderson, E. M. (1988b). Strategic implications of Darwinian economics for selling efficiency and choice of integrated or independent sales forces. Management Science, 34(5), 599–618.

Anderson, E. M., & Gatignon, H. (1986). Modes of foreign entry: a transaction cost analysis and propositions. Journal of International Business Studies, 11, 1–26.

Anderson, E. M., & Schmittlein, D. (1984). Integration of the sales force: an empirical examination. The Rand Journal of Economics, 15(Autumn), 385–395.

Anderson, E. M., & Robertson, T. (1995). Inducing multi-line salespeople to adopt house brands. Journal of Marketing, 59(April), 16–31.

Arrow, K. J. (1969). The organization of economic activity: Issues pertinent to the choice of market versus nonmarket allocation. In The analysis and evaluation of public expenditure: The PPB system. Vol. 1, U.S. Joint Economic Committee, 91st Congress, 1st Session, 59–73. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Barnard, C. (1938). The functions of the executive. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (fifteenth printing, 1962).

Bolton, P., & Dewatripont, M. (2005). Contract theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Carson, S. J. (2000). Managing creativity and innovation in high-technology interfirm relationship. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, United States.

Coase, R. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405. Reprinted in O. E. Williamson and S. Winter (Eds), 1991, The nature of the firm: Origins, evolution, development (pp. 18–33). New York: Oxford University Press.

Coase, R. (1960). The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 3(1), 1–44.

Coase, R. (1993). Coase on posner on coase. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 149, 96–98.

Coase, R. (1972). Industrial organization: A proposal for research. In V. R. Fuchs (Ed.), Policy issues and research opportunities in industrial organization (pp. 59–73). New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Commons, J. R. (1932). The problems of correlating law, economics, and ethics. Wisconsin Law Review, 8, 3–26.

Coughlan, A. T., Anderson, E. M., Stern, L. W., & El-Ansary, A. I. (2006). Marketing channels (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Demsetz, H. (1968). Why regulate utilities? Journal of Law and Economics, 11, 55–66.

Dixit, A. (1996). The making of economic policy: A transaction cost politics perspective. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dutta, S. (1990). The influence of buyer switching costs on second-sourcing: theoretical analysis and experimental evidence. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, United States.

Elster, J. (1994). Arguing and bargaining in two constituent assemblies, upublished manuscript, remarks given at the University of California, Berkeley.

Friedman, M. (1997). In B. Snowdon and H. Vane, “Modern macroeconomics and its evolution from a monetarist perspective”. Journal of Economic Studies, 24(4), 191–221.

Gatignon, A., & Gatignon, H. (2010). Erin Anderson and the path breaking work of TCE in new areas of business research: transaction costs in action. Journal of Retailing, 86(3), 232–247.

Georgescu-Roegen, N. (1971). The entropy law and economic process. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M., & Kumar, N. (2006). Make, buy, or ally: a meta-analysis of transaction cost theory. Academy of Management Journal, 49(3), 519–543.

Ghosh, M., & John, G. (2009). When should original equipment manufacturers use branded component contracts with suppliers? Journal of Marketing Research, 46(October), 597–611.

Goldberg, V. (1976). Toward an expanded economic theory of contract. Journal of Economics Issues, 10(March), 45–61.

Grossman, S. J., & Hart, O. D. (1986). The costs and benefits of ownership: a theory of vertical and lateral integration. Journal of Political Economy, 94(August), 691–719.

Guiltinan, J. P. (1974). Planned and evolutionary changes in distribution channels. Journal of Retailing, 50, 74–79.

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The uses of knowledge in society. American Economic Review, 35(September), 519–530.

Heide, J. B. (1987). Explaining ‘Closeness’ in industrial purchasing relationships: The effects of dependency symmetry on inter-organizational coordination patterns. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison, United States.

Heide, J. B., & John, G. (1990). Alliances in industrial purchasing: the determinants of joint action in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 27, 24–36.

Henisz, W. J., & Macher, J. T. (2004). Firm- and country-level tradeoffs and contingencies in the evaluation of foreign investment: the semiconductor industry, 1994–2002. Organization Science, 15(5), 537–554.

Jap, S. D., & Anderson, E. (2007). Safeguarding interorganizational performance and continuity under ex post opportunism. Management Science, 49, 1684–1701.

John, G., & Reve, T. (2010). Transaction cost analysis in marketing: looking back, moving forward. Journal of Retailing, 86(3), 248–256.

John, G., & Weitz, B. A. (1988). Forward integration into distribution: an empirical test of transaction cost analysis. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 4(Fall), 121–139.

Joskow, P. L. (1985). Vertical integration and long-term contracts. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 1(Spring), 33–80.

Joskow, P. L. (1987). Contract duration and relationship-specific investments. The American Economic Review, 77(March), 168–185.

Klein, B., Crawford, R. G., & Alchian, A. A. (1978). Vertical integration, appropriable rents, and the competitive contracting process. Journal of Law and Economics, 21(2), 297–326.

Klein, B., & Leffler, K. B. (1981). The role of market forces in assuring contractual performance. Journal of Political Economy, 89(August), 615–641.

Kreps, D. M. (1999). Markets and hierarchies and (Mathematical) economic theory. In G. Carroll & D. Teece (Eds.), Firms, markets, and hierarchies (pp. 121–155). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1970). The structure of scientific revolutions (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Macher, J. T., & Richman, B. D. (2008). Transaction cost economics: an assessment of empirical research in the social sciences. Business and Politics, 10(1), 1–63.

Masten, S. (1984). The organization of production: evidence from the aerospace industry. Journal of Law and Economics, 27(October), 403–418.

Masten, S., & Crocker, K. (1985). Efficient adaptation in long term contracts: take or pay provisions for natural gas. The American Economic Review, 75(December), 1085–1096.

Monteverde, K., & Teece, D. (1982). Supplier switching costs and vertical integration in the automobile industry. Bell Journal of Economics, 13(Spring), 206–213.

Newell, A. (1990). United theories of cognition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Noordweier, T. G. (1986). Explaining contract purchase arrangements in industrial buying: A transaction cost perspective,” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, WI, United States.

Ouchi, W. G. (1977). Review of markets and hierarchies. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22(September), 541–544.

Posner, R. A. (1972). The appropriate scope of regulation in the cable television industry. The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 3, 98–129.

Rao, R. S. (2009). Estimating the costs of mistaken governance: The cost of salesforce compensation, Working Paper, Marketing Department, University of Texas, Austin, United States.

Rindfleisch, A., & Heide, J. B. (1997). Transaction cost analysis: past, present and future applications. Journal of Marketing, 61(4), 30–51.

Rindfleisch, A., Antia, K., Bercovitz, J., Brown, J. R., Cannon, J., Carson, S. J., et al. (2010). Transaction cost, opportunism and governance: contextual considerations and future research opportunities. Marketing Letters, 21, 211–222.

Robinson, S. (1968). New York State Bar Association, Antitrust Symposium, p. 29.

Simon, H. (1957). Models of man. New York: Wiley.

Simon, H. (1992). Economics, bounded rationality, and the cognitive revolution. Brookfield: Edward Elgar.

Solow, R. (2001). A native informant speaks. Journal of Economic Methodology, 8(1), 111–112.

Tadelis, S. (2010). Williamson’s contribution and its relevance to 21st century capitalism. California Management Review, 52(2), 159–166.

Tadelis, S., & Williamson, O. (2011). Transaction-cost economics. In R. Gibbons and J. Roberts (Eds), The handbook of organizational economics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Weiss, A., & Anderson, E. M. (1992). Perceptions of legitimacy as a motive to change inter-organizational relations. Stanford Graduate School of Business, Research Paper No. 1175, 1–24.

Whinston, M. (2001). Assessing property rights and transaction-cost theories of the firm. The American Economic Review, 91(2), 184–188.

Williamson, O. E. (1970). Administrative decision making and pricing. In J. Margolis (Ed.), The analysis of public output (pp. 115–135). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Williamson, O. E. (1971). The vertical integration of production: market failure considerations. The American Economic Review, 61(2), 112–123.

Williamson, O. E. (1975). Markets and hierarchies: Analysis and antitrust implications. New York: Free Press.

Williamson, O. E. (1976). Franchise bidding for natural monopolies—in general and with respect to CATV. Bell Journal of Economics, 7, 73–104.

Williamson, O. E. (1979). Transaction cost economics: the governance of contractual relations. Journal of Law and Economics, 22, 233–261.

Williamson, O. E. (1983). Credible commitments: using hostages to support exchange. The American Economic Review, 73, 519–540.

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The economic institutions of capitalism. New York: Free Press.

Williamson, O. E. (1988). Corporate finance and corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 43(July), 567–591.

Williamson, O. E. (1991). Comparative economic organization: the analysis of discrete structural alternatives. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 269–296.

Williamson, O. E. (1993). Calculativeness, trust, and economic organization. Journal of Law and Economics, 36, 453–486.

Williamson, O. E. (1996a). The mechanisms of governance. Oxford University Press.

Williamson, O. E. (1996b). Transaction cost economics and the Carnegie connection. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 31, 149–155.

Williamson, O. E. (1999). Strategy research: governance and competence perspectives. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 1087–1108.

Williamson, O. E. (2000). The new institutional economics: taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38, 595–613.

Williamson, O. E. (2003). Economics and antitrust enforcement: transition years. Antitrust, 17(Spring), 61–65.

Williamson, O. E. (2005). The economics of governance. The American Economic Review, 95, 1–18.

Williamson, O. E. (2008). Transaction cost economics: the precursors. Economic Affairs, 28, 7–14.

Williamson, O. E. (2009). Pragmatic methodology: a sketch, with applications to transaction cost economics. Journal of Economic Methodology, 16, 145–157.

Williamson, O. E. (2010). Transaction cost economics: the natural progression. The American Economic Review, 100(3), 673–690.

Wilson, E. O. (1999). Consilience. New York: Knopf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

This Appendix was prepared by Oliver Williamson at the suggestion of the Editor of the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science.

Transaction cost economics: background and successive developments

With the benefit of hindsight, transaction cost economics had its origins in “four forces.” The first was Ronald Coase’s classic article on “The Nature of the Firm” (1937).Footnote 16 The second was the 3 years from 1960 to 63 that I spent as a student in the PhD program at the Graduate School of Industrial Administration, Carnegie Mellon University.Footnote 17 The third was the demonstration by Coase (1960) and Arrow (1969) that pushing the logic of zero transaction costs to completion revealed that there would never be an occasion for government intervention to correct for externalities or successive stages of production (vertical integration)—because costless contracting would everywhere be efficient.Footnote 18 And the fourth was my experience as Special Economic Assistant to the Head of the Antitrust Division in the United States Department of Justice, 1966–67.Footnote 19(Williamson 2003)

Individually and collectively, these four factors persuaded me that the field of Industrial Organization erred by focusing almost entirely on market structure to the neglect of internal organization, a practice that led frequently to wrong-headed public policy—of which the “inhospitality tradition” is an example. (Stanley Robinson, 1968)Footnote 20 But where to start?

Early beginnings

My paper “The Vertical Integration of Production: Market Failure Considerations” (1971) re-examined vertical integration in comparative contractual terms, with emphasis on the details of alternative modes of governance (markets and hierarchies) in relation to the attributes of transactions, to include express provision for plausible behavioral attributes of human actors.Footnote 21 Economists did not flock to it, and I initially thought of it as a stand-alone paper. In the process of addressing other puzzles with my students, however, I discovered that many contractual phenomena could be interpreted as variations on a theme. Also, what appear to be non-contractual phenomena can often be reformulated in contractual terms.Footnote 22 Vertical integration would turn out to be a paradigm problem!

Markets and Hierarchies (1975) was an effort to build out from the vertical integration problem to examine the employment relation, the limits of firm size, divisionalization and the modern corporation, and applications to public policy. Chapter 1 observes that a “New Institutional Economics” is in progress, which is the first mention of this new field of study.

Chapter 2 of Markets and Hierarchies sets out the “Organizational Failures Framework” with reference to (1) bounded rationality and uncertainty/complexity, (2) opportunism and small numbers, (3) information impactedness, and (4) atmosphere (informal organization). I also observe that the assumption of two-way common knowledge needs to be extended to three-way common knowledge if the courts are called upon to settle disputes, information is impacted, and opportunism is operative. Three- way common knowledge is a much more demanding condition and undermines the purported efficacy of two-way common knowledge in the study of complex contracts.

My paper on “Franchise Bidding for Natural Monopoly—In General and With Respect to CATV” (1976) had its origins in views advanced by the Chicago School that franchise bidding was a general purpose solution to the problem of natural monopoly (Demsetz 1968), as illustrated by its applications to CATV (Posner 1972). Relying, as Demsetz did, on a very simple example (automobile license plates), I was skeptical of its general relevance. I also questioned its efficacy for CATV in the early 1970s. Not only would the non-redeployability of specific assets pose problems at the contract renewal interval, but a focused case study of “bidding competition” in Oakland, California, that I undertook as well as earlier experience that I had with CATV in New York City (Williamson 1970) revealed that politics posed a lurking hazard . Here as elsewhere, the action was in the microanalytics of transactions and governance structures, as examined through the focused lens of contract/governance.

TCE’s codification

The article, however, that broke the ice was my 1979 paper “Transaction Cost Economics: The Governance of Contractual Relations.”Footnote 23 What this article accomplished was to breathe operational content into transaction cost economics in a more concerted and transparent way than had been done previously. The critical dimensions with respect to which the transaction (the unit of analysis) varied were expressly named. Similarly, the internally consistent syndromes of attributes that define alternative modes of governance were set out. Upon taking economizing on transaction costs to be the main purpose of organization, a predictive theory of economic organization was at hand. This was the hitherto missing piece to which young scholars in business (including marketing) and the social sciences were quick to pick up on.

My paper “Credible Commitments: Using Hostages to Support Exchange” (1983) can be thought of as a precursor to my interpretation of the “Commons Triple,” as expressed by John R. Commons: “The ultimate unit of activity … must contain in itself the three principles of conflict, mutuality, and order. This unit is a transaction” (1932, p. 4). Inasmuch as I was already treating the transaction as the basic unit of analysis, I was pleased that Commons concurred. But while I was intrigued by the triple of conflict, mutuality, and order, I was unsure what to make of it. My work on credible commitments led me to interpret governance as the means by which to infuse order, thereby to mitigate conflict and realize mutual gains—which is a constructive way by which to think about contracting.

The Economic Institutions of Capitalism (1985) is my most cited book. It draws upon and integrates published papers on TCE between 1975 and 1984, including public policy ramifications for antitrust, regulation, and corporate governance. It also includes a chapter dealing expressly with the incentive and bureaucratic limits of hierarchy, which was then and remains today an underdeveloped area of study. It being my ambition to breathe operational content into Ronald Coase’s concept of transaction cost, I was understandably pleased when Coase opined that “In a real sense, transaction cost economics, through his writing and teaching, is his [Williamson’s] creation” (1993, p. 98).Footnote 24

Extensions

Although I viewed my 1983 paper on “Credible Commitments” as having made provision for hybrid contracting, locating it between the polar extremes of simple market exchange on the one hand and unified ownership (hierarchy) on the other, that view did not register with many students of organization outside of the economics community. It was mainly for that reason that I submitted my paper on “Comparative Economic Organization” to the Administrative Science Quarterly (1991). Not only does this paper describe the hybrid mode of organization more fully and carefully than earlier efforts, but it also makes the case that each generic mode of organization is supported by a distinctive form of contract law—where (1) contract as legal rules applies to simple market exchange, (2) contract as framework is a more flexible form of contract law and applies to the hybrid mode, and (3) forbearance contract, wherein the firm is its own court of ultimate appeal, applies to hierarchy. I also briefly discuss problems of disequilibrium contracting.

The Mechanisms of Governance (1986) concentrates on developments in transaction cost economics between 1985 and 1995, of which the treatment of hybrids (1991) and trust (1993) are two. A precautionary chapter on applied welfare economics makes the case for the Remediableness Criterion. Inasmuch as all feasible modes of organization, public and private alike, are flawed in relation to a hypothetical ideal, the normative public policy practice of “supposing that … policy was made by an omnipotent, omniscient, and benevolent dictator” (Dixit 1996, p. 8) plainly biases public policy in favor of intervention. The Remediableness Criterion is proposed as a means by which to relieve this bias; specifically, an extant mode for which no superior feasible alternative can be described and implemented with expected net gains is presumed to be efficient. To be sure, this is a rebuttable presumption. Applied welfare economics is moved to much more solid ground by eschewing the fanciful constructions upon which normative pubic policy was based.

The strategy field and literature have grown rapidly over the past 20 years. Transaction cost economics relates but differs (Williamson 1999). It relates in that the governance of contractual relations has strategic ramifications for the viability of a firm—as revealed by governance errors both past (the undervaluation of outsourcing at the River Rouge plant of Ford Motor Company (Williamson 1985, pp. 119–120)) and recent (the excesses of outsourcing at Boeing Aircraft with the Dreamliner (Tadelis 2010)), the lesson of which is to introduce TCE reasoning when making outsourcing decisions in the future. Viewing debt and equity as modes of governance (as well as modes of finance) also has strategic lessons. More generally, since TCE has ramifications for any issue that arises as or can be reformulated in contractual terms and since many of these lessons are consequential, the strategic uses of TCE are endless.

Strategy nevertheless raises broader issues, of which the concept of core competence is one. The problem here is that the concept of core competence, like that of transaction cost in its earlier years, has not been operationalized—with the result that ex post rationalization is a chronic concern. If core competence is to strategy as governance is to TCE, then a promising place to start would be to name the attributes with respect to which clusters of core competence are described. Devising an overall strategic plan for the cost effective development of a firm’s core competences would be unarguably important.

The “New Institutional Economics” (NIE) program to which I referred in Markets and Hierarchies (1975) has flourished in the years since. As I discuss in “The New Institutional Economics: Taking Stock, Looking Ahead” (2000), the NIE divides into two main parts: the institutional environment (the rules of the game) and the institutions of governance (the play of the game). TCE relates mainly to the play of the game, but both the informal rules (e.g., customs, norms, traditions, religion) and the formal rules (e.g., property and contract laws and their enforcement as well as the organization of the polity) of the game are also important to the choice of governance structure for managing transactions within and, especially, between nation states (Henisz and Macher 2004). The institutional environment also has a significant influence on innovation, especially leading edge innovation. Considerations of hierarchy (especially public bureaucracy) are important to this last point—which is an important area for future research. Note in this connection that the features of public bureaus to which TCE calls attention are precisely those that describe governance structures more generally: incentive intensity, administrative control, and the applicable law of contract—where, typically, low powered incentives, extensive controls (internal rules, regulations, and administrative apparatus), and weak (forgiving) enforcement mechanisms are associated with public sector bureaucracy. As the recent financial crisis reveals, these features ought to figure more prominently in whether to expand and how to design public sector oversight and administrative agencies.

Coda

My papers, “The Economics of Governance” (2005) and “Transaction Cost Economics, The Natural Progression” (2010) both reflect upon the foundations of TCE and discuss research needs for the future. Full formalization is one. Entrepreneurship (in general and as between nation states) is another. Uncovering and explicating prospective implementation problems that await actual or proposed organizational innovations in the public and private sectors (with emphasis on finance, banking, and health care) are vitally important but much neglected—possibly because such problems reside in the details and will entail combining TCE concepts with deep knowledge of the particulars. More generally, although calculativeness can be pushed to dysfunctional extremes, hard-headed analysis that is mindful of calculative excesses is what applied social science greatly needs. Endless applications of the lens of contract/governance in theoretical, empirical, and public policy respects await—if and as the torch is taken up by a new generation of young scholars.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williamson, O., Ghani, T. Transaction cost economics and its uses in marketing. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 40, 74–85 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0268-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0268-z