Abstract

Although word-of-mouth (WOM) activity has been studied as an outcome variable of other constructs such as satisfaction, less attention has been given to the antecedents and moderators of WOM when considering WOM as a central construct. Hence, we propose a model of WOM antecedents and moderators using a meta-analytic review. The results show that all antecedents have significant effects on WOM activity, with customer commitment showing the strongest effect. The following hypotheses are also supported: (1) WOM valence is a significant moderator, (2) cross-sectional studies show a stronger influence of satisfaction and loyalty on WOM activity than longitudinal studies, and (3) studies of WOM behavior show a weaker link between loyalty and WOM activity than studies of WOM intentions. In addition, we show that satisfaction has a stronger relationship with positive WOM than loyalty, whereas (dis)loyalty has a stronger relationship with negative WOM than does (dis)satisfaction. We discuss this finding based on the different natures of positive and negative WOM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Interpersonal influence has received great attention in social psychology and there is ample evidence for the relevance of interpersonal communications when individuals make choices in different contexts, including those of consumption (Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955). This effect is also investigated in consumer behavior, and its models consider this interpersonal influence when information is sought as well as given (Engel et al. 1995). Empirical studies show that customers are even more likely to rely on these interpersonal communications, known as “word of mouth” (WOM), in the service context because of the intangibility and experiential nature of services (Murray 1991; Zeithaml et al. 1993).

In the marketing context, WOM communications are defined as “informal communications directed at other consumers about the ownership, usage, or characteristics of particular goods and services and/or their sellers” (Westbrook 1987, p. 261). Arndt (1967) defined word of mouth as “oral, person-to-person communication between a perceived non-commercial communicator and a receiver concerning a brand, a product, or a service offered for sale” (p. 190). These definitions are consistent with recent studies about WOM (Gruen et al. 2006; Harrison-Walker 2001; Wangenheim 2005; Wangenheim and Bayón 2007).

There have been a great number of studies about WOM since the frequently cited Arndt (1967) study, although many of these investigations are focused on other constructs, such as satisfaction, and consider WOM merely as one of the behavioral consequences (Mittal et al. 1999; Oliver 1980; Swan and Oliver 1989). A recent investigation by Mazzarol et al. (2007, p. 1478) has emphasized exactly this point in saying, “Little research, however, has addressed antecedents of WOM when considering WOM as a focal construct.” Although the positive effects of the antecedents of WOM, such as satisfaction, loyalty, quality, commitment, trust, and perceived value, are well established in the literature, there is still a lack of integration for the bivariate relationships involving WOM. Hence, we conduct a systematic review of these antecedents using a meta-analysis in order to provide a quantitative integration of the previous studies after adjusting for measurement and sampling error, to make comparisons about the strength of each antecedent in influencing WOM, and to identify studies’ characteristics as possible moderators.

Using the systematic and quantitative meta-analytic review, this study makes several contributions to the field. Primarily, it is the first meta-analytic effort to assess WOM as a focal construct and to investigate its antecedents and moderators. Additionally, it identifies the different methodological approaches and the main antecedents of WOM in empirical studies. It evaluates the moderating effects of studies’ characteristics and different WOM approaches such as WOM valence and WOM incidence. Moreover, it finds that satisfaction has a stronger relationship with positive WOM than loyalty, while (dis)loyalty has a stronger relationship with negative WOM than does (dis)satisfaction. Lastly, it identifies research questions worthy of future investigations into WOM.

Our review is structured as follows. First, we present a conceptual framework with the proposed hypotheses to guide the meta-analysis. Second, we describe the meta-analytic procedures, including the search process, database development, effect sizes computation, and integration. Third, we present a quantitative summary of the adjusted mean effect sizes for the pair-wise relationships between WOM and its antecedents. Fourth, we present the moderating analysis and the test of the different roles of satisfaction and loyalty for positive and negative WOM activity. Finally, we discuss the main findings.

Conceptual framework

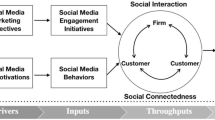

We developed the conceptual framework shown in Fig. 1 based on the literature review of WOM. This meta-analytic framework describes the relationships between WOM and the most investigated antecedents. Although the positive effects of the WOM antecedents depicted in Fig. 1 are well established in the literature, a systematic review of these antecedents using a meta-analysis enables us to make comparisons about the strength of each in influencing WOM.

Among the potential moderators, we focus on WOM valence, WOM incidence, and the studies’ characteristics. It is common for meta-analyses to investigate the variability of effect sizes across studies’ characteristics (Assmus et al. 1984; Pan and Zinkhan 2006). It has been suggested that other variables, such as switching costs and customer experience, could also intervene between WOM and its correlates, but the limited number of studies testing these variables as moderators precluded their assessment in our analyses. The theoretical rationale for the relationships presented in Fig. 1 is discussed next.

Antecedents of WOM

Satisfaction

The dominant model for conceptualizing and measuring customer satisfaction has been the expectancy disconfirmation theory. This view holds that customers evaluate a product or service performance and compare their evaluation with their expectations prior to purchase or consumption (Oliver 1980). In this approach to satisfaction as a post-choice evaluative judgment regarding a specific purchase selection, satisfaction is understood by its transaction-specific component (Oliver 1981). Another approach sees satisfaction as the customers’ evaluations of multiple experiences with the same product or service provider over time (Bolton and Drew 1991), and given that this cumulative construct incorporates previous experiences, the cumulative satisfaction construct will contain an element of customer attitude (Westbrook and Oliver 1991). Subsequent studies, however, have demonstrated that, in addition to the cognitive view, customer satisfaction also contains emotional components (Liljander and Strandvik 1997; Oliver and Westbrook 1993; Straus and Neuhaus 1997). A recent study (Martin et al. 2008) agrees with Zeelenberg and Pieters (2004) in suggesting that emotionally based satisfaction is a stronger predictor of future behavioral intentions than traditional cognitive measures.

The level of customer satisfaction has an influence on two purchase behaviors, namely, repurchase intentions and WOM (Bearden and Teel 1983; Maxham and Netemeyer 2002a, b; Oliver 1980; Ranaweera and Prabhu 2003; Richins 1983). Specifically, the likelihood of customers spreading WOM will depend on their satisfaction level for at least two reasons. First, the extent to which the product or service performance exceeds the customer’s expectations might motivate him or her to tell others about his or her positive experience. In the context of service recovery, for instance, the salience and recency of the experience might explain why satisfaction with the recovery prompts customers to tell family and friends about their positive experience (Maxham and Netemeyer 2002b). Second, to the extent that the customer’s expectations are not fulfilled, possibly creating a customer regret experience, this customer will engage in WOM behavior as a form of “venting” his or her negative emotions, such as anger and frustration, reducing anxiety, warning others, and/or seeking retaliation (Anderson 1998; Oliver 1997; Richins 1984; Sweeney et al. 2005).

Indeed, there are a number of studies supporting the significant effect of satisfaction on WOM (Brown et al. 2005; Heckman and Guskey 1998; Heitmann et al. 2007; Hennig-Thurau et al. 2002; Mittal et al. 1999; Price and Arnould 1999; Söderlund 2006; Swan and Oliver 1989; Wangenheim and Bayón 2007). Thus, our conceptual framework proposes:

-

H1a: There is a significant positive effect of satisfaction on WOM activity.

Loyalty

Loyalty is defined in the marketing context as “an intention to perform a diverse set of behaviors that signal a motivation to maintain a relationship with the focal firm, including allocating a higher share of the category wallet to the specific service provider, engaging in positive word of mouth (WOM), and repeat purchasing” (Sirdeshmukh et al. 2002, p. 20). Note that this conceptualization considers positive WOM as a component of loyalty. This approach is common in a great number of studies in the marketing literature (Bloemer et al. 1999; Jones and Sasser 1995; Jones and Taylor 2007; Lam et al. 2004; Zeithaml et al. 1996), and we found that it was employed in 40 studies reviewed in our meta-analysis. These studies could not, however, be included because they did not present specific results for the WOM construct.

However, a recent study has questioned this “cocktail approach” in which loyalty is measured by an aggregated mix of items that form different components of loyalty (Söderlund 2006). Söderlund (2006) states that this approach is commonly used to include repatronage intentions and WOM intentions as items of a unidimensional loyalty construct. Two empirical studies conducted by Söderlund (2006) support the argument that repurchase intentions and WOM should be considered as separate constructs and the “cocktail approach” should be avoided. There are also other authors modeling repurchase intentions and WOM as independent constructs, including Blodgett et al. (1993), Gruen et al. (2006), Jones and Reynolds (2006), Maxham (2001), and Maxham and Netemeyer (2002a, b).

Dick and Basu (1994) called attention to the fact that there were few studies investigating the influence of loyalty on WOM. Yet, even after a decade, there have been very few studies which have empirically tested the unidirectional effect of loyalty on WOM (Carpenter and Fairhurst 2005; Gounaris and Stathakopoulos 2004; Reynolds and Arnold 2000; and Sichtmann 2007). It is more common to measure the bi-directional association (correlation) between these two constructs when considering them as behavioral outcomes, especially of customer satisfaction (Arnett et al. 2003; Gremler and Gwinner 2000; Jones and Reynolds 2006; Macintosh 2007; Maxham and Netemeyer 2002a, b, 2003; Price and Arnould 1999; Reynolds and Beatty 1999; Söderlund 1998). Thus, because of the availability of the correlations between loyalty and WOM, we could test the effects of loyalty on WOM in our meta-analysis.

Loyalty is hypothesized as an antecedent of WOM because to the extent customers are more loyal to a given provider, they are also more likely to (1) give positive recommendations of the company to the individuals in their reference group (friends and relatives), (2) have greater motivation for processing new information about the company, and (3) have stronger resistance to being persuaded by contrary information (Dick and Basu 1994, p. 107). Moreover, in a disloyalty situation, in which customers switch providers, they are also likely to spread negative WOM about the provider in order to reduce their cognitive dissonance (Wangenheim 2005). In other words, they try to convince themselves about their decision by convincing others, which is one of the strategies often used for reducing post-decision dissonance. As mentioned before, customers might also engage in negative WOW for other reasons such as to release negative emotions, to warn others, and/or to retaliate (Richins 1984; Sweeney et al. 2005). Based on this rationale, we propose:

-

H1b: There is a significant positive effect of loyalty on WOM activity.

Quality

Our framework focuses on quality of services, rather than that of products, because the available studies do so. Only one of the observations investigated a product, namely an e-CRM software. We show in the “Results” section that this observation produced findings similar to those studies investigating services.

Different models have been proposed to measure and evaluate the determinants of service quality. Parasuraman et al. (1985, 1988) developed the SERVQUAL model in which quality is evaluated from the eyes of the customers and defined as the discrepancy between customers’ expectations or desires and their perceptions. In other words, quality is understood as the ability to meet or exceed customers’ expectations. The instrument proposed by these authors (SERVQUAL) suggests that service quality is composed of five dimensions—tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy.

Customers’ perceptions of service quality have an important relationship with their behavioral responses, especially loyalty and WOM. For WOM, when evaluations of service quality are high, the customer’s behavioral intentions in terms of recommendations are favorable, strengthening the relationship between customers and the company (Parasuraman et al. 1988; Zeithaml et al. 1996). On the other hand, when customers perceive service performance as inferior, they are likely to manifest complaining behavior, including private responses (negative WOM) and/or defection (Zeithaml et al. 1996). Hence, customers recommend the company to others when they perceive high service quality and spread negative WOM when they perceive low service quality.

Empirical studies have demonstrated that service quality is a relevant predictor of WOM (Bloemer et al. 1999; Boulding et al. 1993; Harrison-Walker 2001; Zeithaml et al. 1996). A positive relationship presented in these studies demonstrates that the higher (lower) the perceived quality, the higher (lower) the WOM activity of the customers. Based on this discussion, we propose:

-

H1c: There is a significant positive effect of quality on WOM activity.

Commitment

Commitment can be defined as “an enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship” (Moorman et al. 1992, p. 316). This definition is in agreement with Dwyer et al. (1987) conceptualization of buyer-seller relationships and is also consistent with Morgan and Hunt’s (1994, p. 23) definition of commitment as “an exchange partner believing that an ongoing relationship with another is so important as to warrant maximum efforts at maintaining it.” Commitment is measured in the marketing literature either as a multidimensional construct (Gruen, Summers, and Acito 2000) or a unidimensional construct (Morgan and Hunt 1994). In the multidimensional approach, commitment is composed of “affective” (positive emotional attachment), “continuance” (perceived costs associated with leaving the organization), and “normative” (perceived moral obligation toward the organization) commitment. Some authors consider two dimensions, namely “affective” and “high-sacrifice (calculative) commitment” (Fullerton 2003; Harrison-Walker 2001; Jones et al. 2007). While the former is related to the customer identification with, and involvement in, a particular organization, the latter refers to the customer’s sense of being “locked in” to the service provider, due to constraints like loss of benefits and costs for switching provider. On the other hand, the unidimensional approach measures commitment as an overall evaluation of the customers’ engagement with the organization.

Higher commitment customers (relationship-oriented customers) are those who also present higher identification with the company and hold feelings of attachment to maintaining valued relationships, reflecting the affective dimension of the construct (Harrison-Walker 2001). Moreover, customers are more likely to increase their commitment with companies that recognize and reward their status of special customer (Lacey et al. 2007). Therefore, these customers are likely to provide favorable WOM about the company as a need to reinforce their decision to enter the relationship as a good one. Even when experiencing lower levels of satisfaction, these customers are likely to endorse the company in order to keep cognitive consistency and justify their favorable attitude and strong identification with the company (Brown et al. 2005).

Indeed, Brown et al. (2005) have demonstrated in their longitudinal study that for higher-commitment customers, positive WOM behavior is less dependent on the satisfaction level. The reason is that high-commitment customers talk positively about the company regardless of their satisfaction level, whereas low-commitment customers will provide favorable recommendations to the extent that they are satisfied. This finding is in agreement with other studies which establish that commitment has a positive relationship with WOM (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2002; Lacey et al. 2007).

Based on the above discussion, we expect that customers with higher commitment would have a greater likelihood of spreading positive WOM because their WOM behavior is stimulated by either (1) a high satisfaction condition (when satisfaction stimulates WOM) or (2) a low satisfaction state (when a cognitive consistency mechanism prompts the customer to endorse the company in order to reduce cognitive dissonance). Hence, we propose:

-

H1d: There is a significant positive effect of commitment on WOM activity.

We noticed in our review that some studies related only the dimensions of commitment (affective and continuance) with WOM without providing a relationship between overall commitment and WOM (Fullerton 2003; Harrison-Walker 2001). Since the meta-analysis had to combine similar studies, we included only those studies that related overall commitment with WOM.

Trust

Trust refers to “a willingness to rely on an exchange partner in whom one has confidence” (Moorman et al. 1993, p. 82). For Morgan and Hunt (1994, p. 23), trust exists “when one party has confidence in an exchange partner’s reliability and integrity.” Thus, confidence and reliability are two important factors for conceptualizing trust in the marketing context. Research in this field has demonstrated that customers’ trust—either in the overall organization or in the employees—is significantly influenced by customers’ satisfaction (Kau and Loh 2006; Morgan and Hunt 1994; Ranaweera and Prabhu 2003; Singh and Sirdeshmukh 2000). These findings show that the higher (lower) the customer’s satisfaction with the organization, the higher (lower) his or her trust in it.

Trust also has an important effect on behavioral constructs, especially on the customer’s propensity to leave or stay with the same service provider (Garbarino and Johnson 1999; Morgan and Hunt 1994; Singh and Sirdeshmukh 2000). Indeed, empirical findings have shown that higher levels of trust are associated with a greater tendency to offer favorable WOM (Garbarino and Johnson 1999; Gremler et al. 2001; Ranaweera and Prabhu 2003). This is based on the rationale that customers mostly provide recommendations to other individuals of their reference group, such as a friend or a relative, and, thus, a customer will be more likely to endorse a provider that he or she has previous experience with and confidence in (Gremler, Gwinner, and Brown 2001). But even when customers are offering advice to others, no matter who the receiver is, there is a risk of being wrong and a WOM giver would not like to be wrong (Mazzarol et al. 2007).

Another possible reason for the influence of trust on WOM is an indirect effect through satisfaction. Trust creates benefits for customers such as lower anxiety, uncertainty, and vulnerability about the transaction. These benefits influence satisfaction, which in turn affects WOM, especially in a service context that is relatively more complex (Garbarino and Johnson 1999; Hennig-Thurau et al. 2002). Based on this discussion, we propose:

-

H1e: There is a significant positive effect of trust on WOM activity.

Perceived value

Customer-perceived value is the “consumer’s overall assessment of the utility of a product based on perceptions of what is received and what is given” (Zeithaml 1988, p. 14), or in other words, a trade-off between benefits or gets (quality, convenience, volume, etc.) and costs or gives (money, time, efforts, etc.).

Previous studies have investigated the influence of service quality on customers’ behavioral intentions (Boulding et al. 1993; Zeithaml 1988). Based on this literature, Hartline and Jones (1996) proposed that perceived value also has an influence on customers’ behavioral intentions, especially on WOM. One explanation is that customers who perceive that they receive relatively high value tend to become more committed to the organization and seek to recommend others of the reference group to become loyal to the same organization (McKee et al. 2006).

Also, perceived value might have an influence on WOM because it is a more tangible signal in the service encounter since it includes price in the “give” component, and price can be considered a more extrinsic and tangible attribute when compared to other cues used to infer service quality by customers, such as competence and responsiveness of employees (Hartline and Jones 1996).

Consistent with the above rationale, perceived value has been hypothesized as a predictor or a correlate of WOM in a number of studies (Durvasula et al. 2004; Gruen et al. 2006; Hartline and Jones 1996; Keiningham et al. 2007; McKee et al. 2006). Given that the majority of these studies are in the services context—only one of the ten observations was related to a product context—our investigation as well focuses on the service context.

Based on the above rationale, we propose:

-

H1f: There is a significant positive effect of perceived value on WOM activity.

Moderators

The different effects found across studies could be due to different approaches to WOM. For example, there are studies measuring positive WOM, others measuring negative WOM, and yet others using both negative and positive items in the WOM construct. There are studies that work with intentions of WOM and others measuring WOM informed behavior. Moreover, studies’ characteristics in terms of methodological designs could also have an influence on the results. These effects are discussed next.

WOM valence

In an effort to develop a scale to measure WOM, Harrison-Walker (2001) conceptualized WOM as being composed by the factors of frequency, number of contacts, detail of the shared information, and praise (valence). Harrison-Walker’s (2001) study eventually showed two dimensions of WOM communications. The first was “WOM activity,” which included aspects of how often the WOM communication takes place, the number of people told, and the quantity of information provided by the sender. The second was “WOM praise,” reflecting the valence of the WOM communication (positive, negative, or neutral). This distinction between WOM activity and WOM valence is a relevant contribution by Harrison-Walker (2001) to the WOM literature, and she proposes that researchers should measure not only the WOM activity but also the WOM valence, which is in agreement with earlier investigations about WOM (Halstead 2002; Halstead and Dröge 1991; Swan and Oliver 1989) as well as with more recent research (Heitmann et al. 2007).

However, most of the studies in the WOM literature measure WOM as a single unidimensional construct, addressing WOM valence only indirectly by measuring the likelihood of positive or negative recommendations. In some instances, studies work with a neutral position, mixing positive and negative measures among the construct.

In our theoretical framework, we follow Harrison-Walker’s (2001) conceptualization of WOM by establishing WOM activity as the outcome variable and WOM valence as a moderator (see Fig. 1). The reason for doing this is that the focus of the reviewed WOM literature is on the aspects of WOM activity, including frequency, number of people told, and amount of shared information (WOM valence is considered only indirectly, as discussed before). In taking this position, we recognize that WOM is not a unidimensional construct, and that we will include under WOM activity studies that measure frequency, relative number of people told or relative quantity of information shared, since these were the facets of WOM activity supported by Harrison-Walker’s (2001) study. WOM valence will be addressed as a moderator by categorizing WOM as positive, negative, or mixed. In the test of this moderation, we evaluate whether the effect of the antecedent on WOM activity differs with the categories of positive, negative, and mixed WOM valence.

This is a common approach for a test of moderators in a meta-analysis (Lipsey and Wilson 2001). In other words, if the effect of a given predictor, such as satisfaction, in the outcome variable (WOM activity) is contingent on a third variable (WOM valence as positive, negative, or neutral), then the predictor-outcome relationship should be analyzed for each condition of the third variable (moderator).

WOM valence has been receiving more attention in recent investigations about WOM, and there is evidence that extremely positive and extremely negative WOM are the most common examples of WOM (Chevalier and Mayzlin 2006; Duan et al. 2008; Mazzarol et al. 2007; Sweeney et al. 2005; Zeelenberg and Pieters 2004). The rationale, as shown in Oliver (1997) and Anderson (1998), is that customers in the extremes of high or low satisfaction are more likely to spread WOM. Indeed, as discussed earlier, research has shown that highly satisfied customers have a desire to tell others about their positive experience (Brown et al. 2005; Söderlund 2006; Swan and Oliver 1989; Wangenheim and Bayón 2007). Thus, we expect that customers spreading positive WOM are those customers who have high satisfaction and, hence, when WOM assumes a positive valence, there will be a direct relationship between satisfaction and WOM (higher satisfaction is associated with higher positive WOM).

On the other hand, we also expect that customers spreading negative WOM are those with the lowest satisfaction levels, such as those experiencing a service failure followed by an unsatisfactory recovery. The reason is that disappointed customers (those with unsatisfied expectations) often experience negative emotions such as regret, frustration, and anger (Bonifield and Cole 2007; Sweeney et al. 2005). As a consequence, they use negative WOM as a way of “venting” their negative emotions and achieving a feeling of relief after commenting on the incident (Sundaram, Mitra, and Webster 1998; Sweeney et al. 2005; Wetzer et al. 2007). Therefore, we expect that customers spreading negative WOM are those with lower satisfaction and, thus, when WOM assumes a negative valence, there will be an inverse relationship between satisfaction and WOM (lower satisfaction is associated with higher negative WOM).

Based on the above discussion, we propose:

-

H2a: Under the condition of positive (negative) WOM valence, there is a direct (inverse) relationship between satisfaction and WOM activity.

The same justification is extended to the relationship between loyalty and WOM. As we discussed in H1b, customers who are more loyal to a company are more likely to spread positive recommendations about this company, either as a cognitive consistency mechanism (Wangenheim 2005) or as part of a self-enhancement motivation, in which customers provide WOM to praise what they have a strong relationship/identification with (Brown et al. 2005; Sundaram et al. 1998). Thus, we expect that customers spreading positive WOM are those who have higher loyalty, which suggests a direct relationship between loyalty and WOM activity for positive WOM valence.

In contrast, we expect that customers spreading negative WOM are those with lower loyalty or in a disloyalty situation, such as those in a condition of complaint with no recovery or dissatisfactory recovery (Voorhees et al. 2006), or those customers who have switched providers and who spread negative WOM about the former provider as a means of reducing cognitive dissonance (Wangenheim 2005). Therefore, if customers spreading negative WOM are those with low or no loyalty, we can propose that when WOM assumes a negative valence, an inverse relationship is expected between loyalty and WOM (lower loyalty is associated with higher negative WOM). Based on this rationale, we propose:

-

H2b: Under the condition of positive (negative) WOM valence, there is a direct (inverse) relationship between loyalty and WOM activity.

WOM incidence

The relationship between an antecedent and WOM can also vary across studies investigating WOM intention and WOM informed behavior. Brown et al. (2005), for example, report a correlation of .74 between satisfaction and WOM when measuring WOM intentions and .35 when measuring WOM informed behavior. Studies measuring WOM intentions might present higher correlations because of the attitudinal nature of the measures. In other words, respondents usually try to keep their responses coherent and those manifesting high (low) satisfaction will be more likely to provide high (low) intentions of behavior. But studies that combine different measures (satisfaction as an evaluation but WOM as a performed behavior) are more likely to capture the “inconsistencies” of customer behavior. For instance, some customers are satisfied, have intentions to provide favorable recommendations, but do not convert this plan into practice because of a lack of opportunity. This is in agreement with previous meta-analyses showing significant differences between measures of intention (intentions vs. estimates of performance) for the link between attitude and behavior (Sheppard et al. 1988). In this review, studies measuring intentions provided stronger correlations, while those measuring estimates of behavior provided weaker correlation. Based on this rationale, we propose:

-

H3a: The relationship between satisfaction and WOM activity is stronger (weaker) when the study measures intentions (reported behavior) of WOM activity.

-

H3b: The relationship between loyalty and WOM activity is stronger (weaker) when the study measures intentions (reported behavior) of WOM activity.

Study characteristics

Differences across studies can also be explained by variations in studies’ characteristics in terms of survey or experiment approach, cross-sectional or longitudinal measures, student or non-student subjects, scenario or non-scenario-based research, and the product or service context. Assmus et al. (1984) suggest that four categories of characteristics might contribute to identifying systematic patterns in a meta-analysis: research context, model specification, measurement methods, and estimation procedure. But since our unit of analysis was bivariate correlations, we looked for systematic differences in the study characteristics. This is a common procedure in meta-analyses using correlations (Henard and Szymanski 2001; Pan and Zinkhan 2006). We propose four characteristics as potential moderators in our framework: method (survey or experiment), design (cross-sectional or longitudinal), subject (student or non-student), and context (product or service).

Experimental versus survey method

The use of experimental or non-experimental investigation might contribute to explaining the variability in the effect sizes. Given that in an experimental context the researcher is able to randomly assign subjects to the different conditions and control the covariates that might influence the results, there is a greater chance of less error variance in the denominator of the effect size and, consequently, there are larger effect sizes (Crosno and Dahlstrom 2008; Geyskens et al. 1998; Pan and Zinkhan 2006). Based on this rationale, we propose:

-

H4a: The relationship between satisfaction and WOM activity is stronger (weaker) for experimental (non-experimental) studies.

-

H4b: The relationship between loyalty and WOM activity is stronger (weaker) for experimental (non-experimental) studies.

Cross-sectional versus longitudinal design

The strength of the relationships between satisfaction, loyalty, and WOM might vary over time, just like consumers’ perceptions may change over time (Maxham and Netemeyer 2002a). Hence, a study that asks the customer to recall the consumption experience or approaches the participant just after the consumption experience is likely to produce associations (between satisfaction time 1 and WOM time 1, for instance) that are stronger when compared to a study that uses measures from different time frames (between satisfaction time 1 and WOM time 2). The rationale is that measuring predictors and criterion variables at the same point in time may produce artifactual covariance independent of the content of the constructs themselves (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Moreover, another common method bias is the respondents’ tendency to maintain consistency in their responses. Hence, if respondents are highly satisfied they will manifest a high propensity toward positive WOM as well as manifested WOM behavior. But if satisfaction is measured in, say, time 1 and WOM in time 2, it is likely that there will be greater heterogeneity in responses. Therefore, this greater heterogeneity is more likely to increase error variance and produce lower effect sizes (Fern and Monroe 1996).

Even when the longitudinal study uses measures that are taken from the same point in time, it is likely that intercorrelations will be different when compared to the ones from the first attempt, just because participants have provided answers before and some time has passed. For instance, Brown et al.’s (2005) longitudinal study presented lower correlations between satisfaction, commitment, and WOM in their second survey. The possible reason might be a dissipation effect because of the time that had elapsed since the consumption experience.

Based on this discussion, we propose:

-

H5a: The relationship between satisfaction and WOM activity is stronger (weaker) for cross-sectional (longitudinal) studies.

-

H5b: The relationship between loyalty and WOM activity is stronger (weaker) for cross-sectional (longitudinal) studies.

Student versus non-student subjects

Sample homogeneity might have an influence on the magnitude of the effect sizes. Student samples are likely to be more homogeneous, while non-student samples are usually heterogeneous. Given that a homogeneous sample tends to give responses that vary less across the scale values, there might be a problem of restricted ranges and attenuated effect sizes (Fern and Monroe 1996). On the other hand, a non-student sample, as a more heterogeneous sample, is more likely to increase error variance, which would also produce weaker effect sizes (Fern and Monroe 1996). However, it is difficult to predict which of these sources of error is bigger than the other. Thus, based exclusively on these influences, we might not be sure about which type of sample would have a weaker or stronger mean effect.

Considering the particular context of WOM activity and the influence of satisfaction and loyalty as antecedents, we could argue that students have greater dependence on their satisfaction and loyalty levels in order to provide recommendations. The reason is that students are more susceptible to reference group influences (Park and Lessig 1977), with greater chance that they actively search for information from opinion leaders. In consequence, students will be more likely to provide WOM when this recommendation is driven by satisfaction and loyalty, given that they have less-solidified cognitive structures than more mature individuals (Park and Lessig 1977). Given this influence in the WOM context, there is a potential consequence of a bias toward stronger effects of satisfaction and loyalty in a student sample when compared to a non-student sample. Based on this rationale, we propose:

-

H6a: The relationship between satisfaction and WOM activity is stronger (weaker) for studies using a student (non-student) sample.

-

H6b: The relationship between loyalty and WOM activity is stronger (weaker) for studies using a student (non-student) sample.

Product versus service context

Services are known as being intangible, perishable, and requiring higher involvement between customers and sellers during the production and consumption process (Parasuraman et al. 1985). As suggested by Palmatier et al. (2006), this close interaction between customers and sellers might make relationships more critical for services. This might also be the case for WOM behavior and its relationship with customer satisfaction and loyalty, since the process of spreading WOM involves relationships between customers and sellers and customers with other customers. Szymanski and Henard (2001), for instance, have found a stronger correlation between satisfaction and repeat purchasing when services rather than products are investigated. Likewise, Grinstein (2008) as well has found a stronger effect for the link between market orientation and innovation consequences for service firms rather than for manufacturing ones. Based on this discussion, we propose:

-

H7a: The relationship between satisfaction and WOM activity is stronger (weaker) for studies in the service (product) context.

-

H7b: The relationship between loyalty and WOM activity is stronger (weaker) for studies in the service (product) context.

The different roles of satisfaction and loyalty for favorable and unfavorable WOM

In the previous section, we proposed WOM valence as a moderator, suggesting that for positive WOM the effect of the antecedents would be a direct one, whereas for negative WOM the effect would be an inverse one. But we also have reason to expect that the antecedent with the strongest effect on WOM differs for positive and negative WOM.

Specifically, research by Sweeney et al. (2005) has empirically demonstrated that positive WOM is more cognitive, more carefully considered, and more associated with service quality-related comments. Conversely, negative WOM is more emotionally based and is passed on more immediately. Thus, negative WOM might be more related to behavioral intentions (has a conative aspect) and positive WOM could have a stronger evaluative (attitudinal) component, driven by careful rational evaluation. Considering that satisfaction is often approached by its cognitive mechanisms and it often has an attitudinal component (Oliver 1980; Westbrook and Oliver 1991), especially when authors measure cumulative satisfaction, it is reasonable to expect that satisfaction (instead of loyalty) will have a stronger relationship with positive WOM, since this type of WOM also depends on cognitive evaluations and is carefully considered before being spread.

On the other hand, negative WOM is passed on more immediately and to a greater number of people. Because of the emotional nature of negative WOM (Schoefer and Diamantopoulos 2008; Sweeney et al. 2005) and its greater correspondence with intentions and behavior, we could expect that (dis)loyalty, instead of (dis)satisfaction, has a stronger relationship with negative WOM. This view is consistent with Samson’s (2006) argument that brand loyalty should have a greater association with negative WOM because negative experiences with a brand usually have a greater impact on repurchase intentions than do positive experiences.

Based on this discussion, we propose:

-

H8: Satisfaction has a stronger relationship with positive WOM than loyalty, while (dis)loyalty has a stronger relationship with negative WOM than does (dis)satisfaction.

Method

Search process and coding of studies

We employed a literature search in different scientific databases in order to identify the studies relevant to our research. First, we searched for “word of mouth” and “recommendation” in abstracts and keywords in each of the 28 marketing-related journals that are included in the Web of Science Journal Citation Reports impact factor (JCR 2006). This journal-by-journal search used Ebsco, Proquest, and Elsevier Science Direct scientific search engines. After that, we conducted a search on Proquest, Ebsco, and Emerald using the phrase “word of mouth” to look in abstracts and keywords. Then we searched for articles and working papers on the internet, using Google Scholar. Finally, we searched for dissertations and theses in Proquest and sent e-mails to the researchers in the domain asking for their published and unpublished works. After completing our search process in November 2007, we obtained a total of 591 studies done in 1955–2007. Of these 591 studies, there was a body of 349 that included theoretical papers, qualitative investigations, quantitative studies that merely cited “word of mouth,” and studies using WOM items inside a loyalty construct (the “cocktail approach”), which left 242 papers. From this amount (242 quantitative studies measuring WOM), we selected 127 (53%) studies, which produced 162 independent samples, 348 effect sizes, and a cumulated N of 64,364 subjects. A list of the studies used in our empirical meta-analysis is available on request.

The remaining 115 studies (242–127) could not be included for several reasons: (1) results were originated from logit/probit models and no correlations were presented (17 studies); (2) WOM was cited/measured in the context of consumer complaining behavior, but it was not related to any of the variables of the proposed model (17 studies); (3) results were reported only in terms of number of recommendations (11 studies); (4) results for WOM were integrated with customer lifetime value and no correlation was presented (five studies); and (5) WOM was measured but it was not related to any of the constructs of the proposed model (65 studies). The inclusion rate of 53% is comparable to other meta-analyses in marketing by Szymanski and Henard (2001; 59%) and Pan and Zinkhan (2006; 56%).

We evaluated each study for measures of the relationship between WOM, its antecedents, and the moderators. Two criteria were used for inclusion: (1) correlational studies had to present the correlation coefficient (r) or the standardized regression coefficient between WOM and any antecedent of the theoretical model and (2) studies of group contrasts had to present the related statistic (t test, F-ratios with one df in the numerator) for the relationship between WOM and any antecedent. We could convert these statistics to r coefficients using common guidelines in meta-analysis (see Lipsey and Wilson 2001, p. 198; Peterson and Brown 2005).

We selected the correlation coefficient r as the primary effect size metric because it is easier to interpret and is a scale-free measure, a common approach for meta-analytical review in the marketing literature (DelVecchio et al. 2006; Eisend 2006, 2004; Franke and Park 2006; Janiszewski et al. 2003; Palmatier et al. 2006; Pan and Zinkhan 2006). In following Peterson and Brown’s (2005) recommendations that a meta-analysis should include the maximum number of effect sizes to make the results more generalizable, we also incorporated those studies that provided only the standardized regression (beta) coefficients. We used the formula suggested by Peterson and Brown (2005) to estimate the correlations from the beta coefficients. The formula used is \(r = .98\beta + .05\lambda \), where λ is a variable that equals 1 when β is non-negative and 0 when β is negative.

We found that from the 162 observations in the data set, 105 (65%) provided the Pearson correlation coefficients, 19 (12%) supplied a t or F statistic of a group contrast, and 38 (23%) were completed with the correlation derived from the beta coefficient. Since the studies we reviewed had a broad array of research designs, using r as the common effect size enabled us to integrate the various research designs. Before pooling the samples, we tested whether studies providing correlations would be different from those in which correlations were derived from beta coefficients but no significant difference was found for the link between satisfaction and WOM (mean r = .39; mean converted r = .22; F = 2.57; p < .112) and between loyalty and WOM (mean r = .31; mean converted r = .43; F = .41; p < .526).

All identified studies were then examined in terms of the following relevant variables: authors, year, journal, method (survey vs. experiment), design (cross-sectional vs. longitudinal), subjects (students vs. non-students), context (product vs. service), WOM valence (positive, negative, or mixed), WOM communication (sent, received, or both), WOM incidence (intention vs. behavior), scenarios (used vs. non-used), total sample size, number of items used to measure each variable, reliability of each variable, and effect sizes.

From our 162 observations, 76 (47%) used the term “repurchase intentions,” 33 (20%) used “loyalty,” two (1%) measured real behavior, and 51 (32%) did not measure this construct. Because most of these studies measured intentions of loyalty, we considered repurchase intentions and loyalty intentions together, naming the construct “loyalty.”

Procedures for effect size integration

The developed database integrated the effect sizes according to common guidelines in the meta-analysis literature (Lipsey and Wilson 2001). Since the true relationship between variables is mainly influenced by sampling and measurement error, correlations were first weighed by the inverse variance and then by the inverse variance corrected for measurement error (cf. Lipsey and Wilson 2001, p. 110). We first converted the original correlations to Fisher’s Z statistic before applying the variance weight and reliability adjustment. After computing the mean values and confidence intervals for Fisher’s Z values, we converted them back to r using the appropriate formulas (cf. Lipsey and Wilson 2001, p. 63–64). We adjusted the effect sizes for unreliability by applying the reliability weight directly to the inverse variance using w’ = w × (r xx ) × (r yy ). In this approach, the effect size is corrected both for sampling and measurement error (Lipsey and Wilson 2001, p. 110).

In view of this approach, we present our effect size integration in three stages, based first on observed correlations, then on correlations weighed by sampling error, and finally on correlations weighed by both sampling and measurement error.

A confidence interval is presented for each effect size and it is significant when it does not include zero. When the mean effect size is significant, a fail safe N is calculated, estimating the number of non-significant and unavailable studies that would be necessary to bring the cumulative effect size to a non-significant value (known as the “file drawer problem;” Rosenthal 1979). This statistic is an indication of the robustness of the results. The formula used is k × (r − r c )/r c , where k is the number of studies, r is the mean effect size, and r c is the “just significant” level or critical effect size (see Lipsey and Wilson 2001, p. 166; Hunter and Schmidt 2004, p. 501). We used a level of .05 as “just significant,” similar to Grewal et al. (1997).

Homogeneity of the effect size distribution was tested by the Q statistic, distributed as a chi-square (see Lipsey and Wilson 2001, p. 115). If the null hypothesis of homogeneity is rejected, differences in effect sizes may be attributed to factors other than sampling error alone, like moderating variables related to studies’ characteristics.

In each relationship in which the Q statistic was significant (heterogeneity evidence), a moderator analysis was performed, considering the studies’ characteristics that were coded based on information provided in the articles. These moderators included method (survey vs. experiment), design (cross-sectional vs. longitudinal), subjects (students vs. non-students), context (products vs. services), WOM valence (positive vs. negative), and WOM incidence (intention vs. behavior).

When studies measured the constructs using single items (141 cases, or 32% of the 442 measurement situations) or when reliability values were unavailable (28, or 9% of the total of 301 situations using two or more items in the measured variables), the reliabilities were estimated using the Spearman–Brown procedure suggested by Hunter and Schmidt (2004, p. 311), which has been used in other meta-analyses in marketing (Franke and Park 2006; Grewal et al. 1997). For instance, of the 162 observations providing effect sizes for WOM, 58 (36%) were based on single items and had an estimated reliability of .711; 9 (6%) observations were based on two items and had an estimated reliability of .831; three (2%) observations were based on three items and had an estimated reliability of .88; and two (1%) observations were based on four items and had an estimated reliability of .908. This same procedure was applied to the other constructs of the model. The advantage of the Spearman–Brown procedure is that the estimated reliability takes into account the number of items used to measure the construct, so that constructs with a greater number of items have higher estimated reliabilities.

Results

Descriptive statistics

After reviewing the sample size of each of the 162 observations in the data set, we identified three outliers. While the sample size of the remaining studies varied from 40 to 1,405, the outliers had sample sizes of 6,201, 3,206, and 1,986 respondents. The distortion of these outliers would be greater for the link between perceived value and WOM, which would be .48 with the inclusion of the outliers and .59 after the exclusion. This difference was caused by the observed effect size of .35 for the link between perceived value and WOM in the outlier with a greater sample size (6,201). All analyses of effect size integration were performed after the outliers were excluded. Because one of the three outliers came from a study that provided more than one observation in the data set, the number of observations, after excluding the outliers, reduced from 162 to 159, but the number of studies from 127 to 125. Thus, the analyses were based on 159 observations from 125 studies.

Table 1 presents the results for the integration of effect sizes of the antecedents of WOM. As we show in Table 1, the correlates of WOM with greater frequency in the literature are satisfaction and loyalty, with 113 and 75 observations respectively. Following Lipsey and Wilson’s (2001) suggestion for analyzing the magnitude of effect sizes (r < .10 as small; r = .25 as medium, and r > .40 as large effect size), we can see in Table 1 that the antecedents of WOM have medium-to-large mean effects for the integrated effect size (corrected for sampling and measurement error), with the relationships varying from .39 (loyalty–WOM) to .66 (commitment–WOM). All the proposed relationships were found to be significant, irrespective of the number of observations. Thus, hypotheses H1a, H1b, H1c, H1d, H1e, and H1f were supported.

We note that only one of the 15 observations in the relationship between quality and WOM dealt with the quality of a product (an e-CRM software). This observation presented a correlation of .53 and a sample of 143 in the dataset. Table 1 shows that the simple average r was .50 while the adjusted r was .53, demonstrating that the only study about products presented a relationship for the link quality-WOM very similar to that of studies investigating services.

Examining the confidence intervals of the antecedents of WOM, we notice that the links satisfaction–WOM and loyalty–WOM have the lowest dispersion around the mean effect. The file drawer N was also higher (greater than 510) for these links, indicating that a higher number of studies with non-significant effect size would be needed in order to reduce the mean effect size to a level of “just significant.” In other words, this result is an indication that the mean effect sizes of satisfaction–WOM and loyalty–WOM are more unlikely to be null, as the greater the file drawer number, the greater our confidence that the mean effect size is not null. For example, to bring the significant link satisfaction–WOM down to the level of .05 (used as the “just significant” level), it would be necessary to find 844 studies with null-results to be included in our analysis. Even the lower file drawer N of 91 studies for the antecedent trust suggests that it is unlikely there is this number of studies finding null results for the effects of trust on WOM.

But a highly heterogeneous subset of effect sizes in the links satisfaction–WOM and loyalty–WOM—as indicated by the Q statistic (see Table 1) and the greater ranges (see columns of minimum and maximum)—also indicates that moderating variables might contribute to explaining the variance in these effect sizes. The analysis of moderators is presented next.

Moderating effects

In order to test if the studies’ characteristics could contribute to explaining the variability in the effect sizes, we conducted an analysis of moderation using regression analysis, with effect sizes as dependent variables (correlations corrected for reliability) and moderators as independent dummy-coded variables, a common approach for testing moderators (Eisend 2006; Szymanski and Henard 2001). An advantage of the regression approach is that it takes into account the variability in the other moderators as well. This procedure is not recommended if there are few effect sizes, namely, a ratio of less than five observations per independent variable, because results might be biased by low statistical power and capitalization on sampling error (Hunter and Schmidt 2004, p. 70). Because the links satisfaction–WOM and loyalty–WOM are the ones with the greater number of observations (90 and 66, respectively), we conducted a separate regression for each of them. The results are presented in Table 2.

Given that WOM valence had three categories (negative, positive, and mixed), one alternative was to use two dummies in the regression model, namely (1) WOM positive (1 for positive WOM and 0 otherwise) and (2) WOM negative (1 for negative WOM and 0 otherwise). However, this procedure would bias the results because mixed WOM was more similar to positive WOM (both presented a positive mean for satisfaction–WOM). Thus, we decided to drop the “mixed WOM” category and use one dummy considering only negative vs. positive WOM.

We see from the findings in Table 2 that the regression models are relatively free of collinearity, since the maximum variance inflation factor (VIF) was below the recommended threshold of 10 (Hair et al. 1998). The models for the satisfaction–WOM and loyalty–WOM relationships presented a high proportion (about 77%) of variance explained by the predictors. These two models were statistically significant at .001 (see Model F and p level).

For the satisfaction–WOM relationship, we see from Table 2 that two moderators were significant predictors. The first significant moderator was the WOM valence (negative vs. positive). The significant positive coefficient (β = .90, p < .001) means that studies measuring positive (negative) WOM presented a direct (inverse) effect of satisfaction on WOM, supporting H2a. The second significant moderator was study design, supporting H5a. The negative coefficient (β = −.10, p < .071) reveals that the effect of satisfaction on WOM was stronger for cross-sectional studies (.42) than for longitudinal studies (.38). A total of 90 observations presented completed information for all predictors and the dependent variable.

The link loyalty–WOM presented a similar pattern when considering that (1) studies measuring positive (vs. negative) WOM presented a direct (inverse) mean effect of loyalty on WOM (β = .88, p < .001) and (2) longitudinal studies presented a lower mean effect size (.29) than cross-sectional investigations (.39), with a significant regression coefficient (β = −.14, p < .031). These findings support H2b and H5b. Furthermore, WOM incidence was significant for loyalty–WOM (β = −.13, p < .037), with the negative coefficient indicating that the association between loyalty and WOM was stronger (.42) for the studies measuring intention of WOM and weaker (.18) for those measuring a reported behavior of WOM, supporting H3b. However, the WOM incidence moderator was not significant in the satisfaction–WOM relationship, not supporting H3a.

We can also see from Table 2 that the influence of satisfaction and loyalty on WOM was not different between studies (1) using experimental versus survey method (no support for H4), (2) researching students or non-student subjects (no support for H6), and (3) investigating the product or the service context (no support for H7).

It is interesting to note that for both the satisfaction–WOM and loyalty–WOM relationships there were strong differences between conditions of positive and negative WOM. These analyses supported the relevant role of WOM valence as a moderator. Next we test whether a change in the WOM valence changes the antecedent that is most strongly associated with WOM activity (H8).

The different roles of satisfaction and loyalty

From the total of 159 observations, 101 (63%) dealt with positive WOM, 31 (20%) with mixed WOM, and 27 (17%) with negative WOM. We proposed in H8 that satisfaction has a stronger relationship with positive WOM than loyalty, while (dis)loyalty has a stronger relationship with negative WOM than does (dis)satisfaction. The segmented results are presented in Table 3.

We can see in Table 3 that for positive WOM, the effects of both antecedents are positive, although satisfaction has a stronger effect (r = .62) when compared to loyalty (r = .54), with a significant difference (z = 6.82, p < .001). Conversely, for negative WOM conditions, the effects of loyalty on WOM are stronger (r = −.58) when compared to the influence of satisfaction (r = −.51), with a significant difference (z = 2.76, p < .003). These findings support H8.

An additional finding, which is in agreement with the previous findings, is that the condition of mixed WOM produced a positive mean effect size for both satisfaction and loyalty, and the effect of satisfaction was stronger (r = .42) when compared to loyalty (r = .30), with a significant difference (z = 3.30, p < .001).

Even if we applied a Bonferroni correction and lowered the alpha level of .05 by the number of comparisons, which would set the alpha for significance at .017 (.05/3 = .017), the findings would still support the difference between satisfaction–WOM and loyalty–WOM for both positive WOM (p < .001) and negative WOM (p < .003). We discuss these findings next.

Discussion and conclusion

The meta-analysis we report in this study provides a quantitative integration of the main constructs that are associated with WOM and a summary of the relationships between these constructs and WOM. Although there have been a great number of studies investigating WOM, there is still a lack of integration for the bivariate relationships involving WOM. Thus, the present meta-analysis seeks to fill this gap by presenting a conceptual framework of the antecedents and moderators of WOM and empirically investigating the hypotheses of this model. Our contributions are derived from this meta-analytic review.

First, the direct-effect analysis reveals that commitment is the main correlate of WOM (r = .66), followed by perceived value (.59), quality (.53), trust (.46), satisfaction (.42), and loyalty (.39). Most of these mean effects can be interpreted as a large effect (greater than .40, Lipsey and Wilson 2001). These findings support the relevant role of the commitment variable in the customer’s propensity to spread recommendations (positive or negative) about the provider, in agreement with Brown et al. (2005), Fullerton (2003), and Lacey et al. (2007).

Second, findings from the multiple regression support the moderating role of WOM valence (H2) because for positive WOM valence, a direct relationship is found between the antecedents (satisfaction and loyalty) and WOM activity. On the other hand, for negative WOM valence, an inverse association was found. This finding supports Szymanski and Henard’s (2001) finding of a link between satisfaction and negative WOM and extends their results to the association between loyalty and WOM.

Third, WOM incidence (intention or behavior) was a significant moderator in the loyalty–WOM relationship (H3b). As expected, evidence from the analysis shows that the influence of loyalty on WOM is significantly lower for studies measuring reported behavior of WOM activity when compared to those measuring intentions of WOM activity. Brown et al.’s (2005) study found a similar result when measuring the influence of satisfaction on WOM activity. This difference in the level of influence can be explained by the attitudinal nature of the WOM intentions measure. So, it is more likely that researchers measuring WOM as the intention to recommend will find a stronger relationship between WOM and other measures, such as loyalty intentions, because respondents often try to maintain a cognitive consistency when answering questionnaire items (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

Fourth, the moderator analysis also revealed that the studies’ design (cross-sectional vs. longitudinal) also had a significant influence in both satisfaction–WOM and loyalty–WOM associations (H5). As hypothesized, cross-sectional studies presented stronger mean effects than longitudinal ones. A possible explanation is that the influence of satisfaction and loyalty on WOM may dissipate over time and if variables are measured just after the consumption experience, they might capture a stronger association between the variables. Another possibility is that the cross-sectional studies could suffer from common-method bias, which would increase the estimated correlations (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

Fifth, there was no difference in the effects of satisfaction and loyalty on WOM when comparing experimental and non-experimental studies (H4), student-based versus non-student-based research (H6), and the service versus the product context (H7). Although the differences between these conditions have been proposed in previous meta-analyses (Crosno and Dahlstrom 2008; Geyskens et al. 1998; Pan and Zinkhan 2006; Szymanski and Henard 2001), the findings from this literature have not provided manifest differences. Our findings show that when controlling for the influence of the other methodological moderators, the effects of satisfaction and loyalty on WOM tend to be similar whether the researcher conducts an experiment or a survey, uses students or not in the sample, and investigates services or products. What does have an effect is the decision to investigate negative or positive WOM, measure WOM intention or behavior, and use a cross-sectional or a longitudinal design.

Sixth, our findings supported the hypothesis that satisfaction has a stronger relationship with positive WOM than loyalty, whereas (dis)loyalty has a stronger relationship with negative WOM than does (dis)satisfaction (H8). This effect can be explained by the differences between behavioral intentions and attitudes. In other words, given that (1) positive WOM is more strongly related to cognitive evaluations and it is carefully considered before being spread (Sweeney et al. 2005), and that (2) satisfaction is often interpreted by its cognitive mechanisms and it often has an attitudinal component (Oliver 1980; Westbrook and Oliver 1991), we could expect satisfaction to have a stronger relationship with WOM activity for positive WOM valence.

On the other hand, because negative WOM is more emotionally based, is passed on more immediately, and therefore has a greater association with an intentional/behavioral component (Schoefer and Diamantopoulos 2008; Sweeney et al. 2005), we can predict that (dis)loyalty is more strongly associated with WOM activity for negative WOM valence than is (dis)satisfaction. This finding is consistent with the notion that negative WOM is usually a behavior of customers who have switched providers (a disloyalty behavior), and then spread negative evaluations of the former provider as a means to reduce cognitive dissonance, to vent negative emotions, to warn others, and/or to seek retaliation (Richins 1984; Sweeney et al. 2005; Wangenheim 2005).

This support for H8 is consistent with a recent study which shows that emotionally based satisfaction is a stronger predictor of future behavioral intentions than traditional cognitive measures (Martin et al. 2008). It is also consistent with the proposition that consumers are more likely to engage in WOM when they experience significant emotional experiences (Dick and Basu 1994; Söderlund and Rosengren 2007). Our meta-analytic review empirically confirms that more emotionally based WOM presents a stronger association with customers’ behavioral intentions.

As the main contribution for managers, the present meta-analysis shows that satisfaction is more associated with positive WOM than loyalty, whereas (dis)loyalty is more associated with negative WOM than is (dis)satisfaction. This finding reinforces the notion that satisfied customers are not necessarily loyal (Matos et al. 2007; Reichheld 1994) and it expands this knowledge by empirically demonstrating that negative and positive WOM are differently associated with key marketing variables (satisfaction and loyalty). While negative WOM has a strong behavioral component, positive WOM is more evaluative and attitudinal-based. An implication of this finding is that managers might “reap” the benefits of positive WOM in the middle or long term as customer satisfaction is “sown.” On the other hand, the damages of negative WOM can be experienced in the short term if customers are dissatisfied and switch providers.

The study’s support for the significant role of customer commitment as an important predictor of WOM activity is another of its contributions to managerial practice. After combining studies and controlling for the effects of sampling and measurement error, the strongest effect of commitment (.66) on WOM indicates that the most important way for managers to increase customers’ likelihood of favorable recommendations could be to increase customers’ commitment to the organization. Fullerton (2003) has demonstrated that the positive effect of commitment on retention is more pronounced when customers are committed through shared values and identification rather than dependence and switching costs. Thus, managers could increase customers’ commitment by improving the identification and the values shared between customers and the company as an incentive for customers’ advocacy.

Limitations and future research directions

Several limitations that are common to meta-analytic reviews in the marketing literature are also present here. For instance, we could not include studies that measured WOM as a component of a broader loyalty or behavioral intentions construct because of the “cocktail approach” used in measurement (Söderlund 2006). We were also not able to include the type of WOM (sent vs. received) as a moderator in the regression because the few cases of received WOM were from studies that did not have complete information for the other moderators (the variable became a constant in the listwise procedure and had to be excluded). Also, our analysis is limited to moderators used in existing studies, and other variables that have been suggested as moderators for WOM, such as switching costs and customer experience, could not be included in our analysis, as is the case in other meta-analyses (see for example Kirca et al. 2005). Moreover, our moderating analysis could be performed only for the antecedents of WOM with the greatest number of observations (satisfaction and loyalty).

Another possible limitation is the fact that the reviewed studies might have methodological weaknesses other than the sample size and the measurement error taken into account in our meta-analysis. Considering, for example, that studies come from different sources, such as dissertations and papers published in journals of different quality, decisions related to design, data collection, and analyses could have an influence on the obtained results. These extraneous sources of error might also contribute to the variability in the effect sizes across studies. Unfortunately, these factors are difficult, if not impossible, to control in the context of a meta-analysis.

Future research should further develop the WOM literature by integrating the perspectives of the WOM recipient and WOM giver, as conducted by Gilly et al. (1998). An extension to this approach could include those (moderating) variables that are relevant to communication theory (Hovland et al. 1953) but which have been omitted in WOM research, such as source credibility, source attractiveness, message congruence, message repetition, situational involvement of the recipient, and risk perceived by the recipient. These variables should be relevant in understanding how the received WOM influences customers’ propensity to pass the information to others.

Another aspect worthy of future investigation is the affective mechanisms related to the situations in which customers provide either positive or negative WOM, since commitment presented a significant association with WOM, and commitment usually reflects a positive affect towards the organization. Correspondingly, future investigations about WOM and its relationship with satisfaction and loyalty could be extended to include specific emotions, such as anger, regret, frustration, and disappointment, in order to understand the likely emotional and behavioral aspect of negative WOM when compared to the more cognitive positive WOM.

Moreover, longitudinal research could examine whether the influence of satisfaction and loyalty on WOM dissipates over time or if the stronger relationships found for the cross-sectional studies are related to the predictor and outcome variables being measured at the same point in time (common-method bias). Considering that WOM researchers are often investigating customers’ relationships with providers, collecting data at more than one point in time might help in producing a more realistic picture of the relationships between customers and companies.

In addition, future research should also test whether the practice of measuring WOM as an intention of recommendation (instead of a manifested real behavior) is leading researchers to believe in a stronger effect when in fact the effect is smaller. Indeed, most consumer researchers grapple with the question of whether to use intentions or behavior in measuring behavioral constructs like WOM. Our review suggests a large and significant difference (.42 versus .18) between these approaches in the WOM context. Hence, researchers should be aware of the serious limitation of measuring only intentions and make efforts to measure real behavior, or even use both intention and behavior measures in order to assess the differences between them.

Furthermore, researchers must ask whether the effects suggested above are influenced by the context of online WOM. Although previous studies have investigated electronic WOM (Gruen et al. 2006; Hennig-Thurau et al. 2004; Stewart and Pavlou 2002), more research is needed to investigate the issues presented here in the online WOM context. It is possible that the differential effect of satisfaction and loyalty on negative and positive WOM is even more pronounced in an online environment, given the great power of dissatisfied customers to use the Internet to vent negative emotions, to warn other customers, or to seek retaliation.

In summary, we provide insight into the antecedents of WOM activity, the approaches and studies’ characteristics that moderate these relationships, and how the influence of satisfaction is more pronounced for positive WOM and (dis)loyalty for negative WOM. We hope these findings provide renewed insights for WOM researchers and advance the theory of WOM communications in marketing.

References

Anderson, E. W. (1998). Customer satisfaction and word-of-mouth. Journal of Service Research, 1(1), 1–14.

Arndt, J. (1967). Word-of-mouth advertising and informal vommunication. In D. Cox (Ed.), Risk taking and information handling in consumer behaviour. Boston: Harvard University.

Arnett, D. B., German, S. D., & Hunt, S. D. (2003). The identity salience model of relationship marketing successes: the case of nonprofit marketing. Journal of Marketing, 67, 89–105 April.

Assmus, G., Farley, J. U., & Lehmann, D. R. (1984). How advertising affects sales: meta-analysis of econometric results. Journal of Marketing Research, 21(1), 65–74.

Bearden, W. O., & Teel, J. E. (1983). Selected determinants of consumer satisfaction and complaint reports. Journal of Marketing Research, 20(1), 21–28.

Blodgett, J. G., Granbois, D. H., & Walters, R. G. (1993). The effects of perceived justice on complainants’ negative word-of-mouth behavior and repatronage intentions. Journal of Retailing, 69(4), 399–428.

Bloemer, J., de Ruyter, K., & Wetzels, M. (1999). Linking perceived service quality and service loyalty: a multi-dimensional perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 33(11/12), 1082–1106.

Bolton, R. N., & Drew, J. H. (1991). A longitudinal analysis of the impact of service changes on customer attitudes. Journal of Marketing, 55(1), 1–10.

Bonifield, C., & Cole, C. (2007). Affective responses to service failure: anger, regret, and retaliatory versus conciliatory responses. Marketing Letters, 18(1), 85–99.

Boulding, W., Kalra, A., Staelin, R., & Zeithaml, V. A. (1993). A dynamic process model of service quality: from expectations to behavioural intentions. Journal of Marketing Research, 30(1), 7–27.

Brown, T. J., Barry, T. E., Dacin, P. A., & Gunst, R. F. (2005). Spreading the word: investigating antecedents of consumers’ positive word-of-mouth intentions and behaviors in a retailing context. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33(2), 123–138.

Carpenter, J. M., & Fairhurst, A. (2005). Consumer shopping value, satisfaction, and loyalty for retail apparel brands. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 9(3), 256–269.

Chevalier, J., & Mayzlin, D. (2006). The effect of word of mouth on sales: online book reviews. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(3), 345–354.

Crosno, J. L., & Dahlstrom, R. (2008). A meta-analytic review of opportunism in exchange relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(2), 191–201.

DelVecchio, D., Henard, D. H., & Freling, T. H. (2006). The effect of sales promotion on post-promotion brand preference: a meta-analysis. Journal of Retailing, 82(3), 203–213.

Dick, A. S., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(2), 99–113.

Duan, W., Gu, B., & Whinston, A. B. (2008). The dynamics of online word-of-mouth and product sales – an empirical investigation of the movie industry. Journal of Retailing, 84(2), 233–242.

Durvasula, S., Lysonski, S., Mehta, S. C., & Tang, B. P. (2004). Forging relationships with services: the antecedents that have an impact on behavioral outcomes in the life insurance industry. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 8(4), 314–326.

Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 51, 11–27 April.

Eisend, M. (2004). Is it still worth to be credible? A meta-analysis of temporal patterns of source credibility effects in marketing. In B. Kahn, & M. F. Luce (Eds.), Advances in consumer research, vol. 31 (pp. 352–357). Urbana: Association of Consumer Research.

Eisend, M. (2006). Two-sided advertising: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 23(2), 187–198.

Engel, J. F., Blackwell, R. D., & Miniard, P. W. (1995). Consumer behavior (8th ed.). Orlando: Dryden.

Fern, E. F., & Monroe, K. B. (1996). Effect-size estimates: issues and problems in interpretation. Journal of Consumer Research, 23, 89–105 September.

Franke, G. R., & Park, J.-E. (2006). Salesperson adaptive selling behavior and customer orientation: a meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(4), 693–702.

Fullerton, G. (2003). When does commitment lead to loyalty? Journal of Service Research, 5(4), 333–344.

Garbarino, E., & Johnson, M. S. (1999). The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 70–87.

Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M., & Kumar, N. (1998). Generalizations about trust in marketing channel relationships using meta-analysis. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 15(3), 223–249.

Gilly, M. C., Graham, J. L., Wolfinbarger, M. F., & Yale, L. J. (1998). A dyadic study of interpersonal information search. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26(2), 83–100.

Gounaris, S., & Stathakopoulos, V. (2004). Antecedents and consequences of brand loyalty: an empirical study. Journal of Brand Management, 11(4), 283–306.

Gremler, D. D., & Gwinner, K. P. (2000). Customer-employee rapport in service relationships. Journal of Service Research, 3(1), 82–104.

Gremler, D. D., Gwinner, K. P., & Brown, S. W. (2001). Generating positive word-of-mouth communication through customer-employee relationships. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 12(1), 44–59.

Grewal, D., Kavanoor, S., Fern, E. F., Costley, C., & Barnes, J. (1997). Comparative versus noncomparative advertising: a meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing, 61(4), 1–15.

Grinstein, A. (2008). The effect of market orientation and its components on innovation consequences: a meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(2), 166–173.

Gruen, T. W., Osmonbekov, T., & Czaplewski, A. J. (2006). eWOM: the impact of customer-to-customer online know-how exchange on customer value and loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 59(4), 449–456.