Abstract

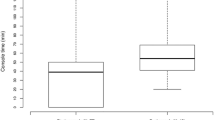

To examine whether utilizing an employed surgical first assistant or a physician as an assistant during gynecologic robotic cases affects surgical variables. A high volume gynecologic oncologist’s robotic case data spanning fourteen years (2005–2018) was analyzed. We separated the cases based on the type of assistant used: either an employed surgical first assist or another physician. The assisting physicians were either members of the same practice or general gynecologists in the community. The two groups were compared for console time and estimated blood loss. We controlled for patient Body Mass Index (BMI), uterine weight, use of the fourth robotic arm, benign versus malignant pathology, and the surgeon’s subjective estimate of the difficulty of the case using a conventional laparoscopic versus robotic approach. Cases with an employed surgical assist had a mean adjusted robotic console time that was 0.32 h (19.2 min) faster than cases with a physician as the assist (95% CI 0.26 h–0.37 h faster, p < 0.001). Cases with an employed surgical assist also had an estimated blood loss (EBL) that was 47.5 cc lower than cases with a physician assisting (95% CI 38.8 cc–56.3 cc lower EBL, p < 0.001). The use of an employed surgical assist was associated with a faster console time and lower blood loss compared to using an available physician even adjusting for confounding factors. This deserves further exploration, particularly in regards to complication rates, operating room efficiency, utilization of health care personnel, and cost.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Upon request.

Code availability

Data were analyzed in STATA version 16.

References

Nayyar R, Yadav S, Singh P, Dogra PN (2016) Impact of assistant surgeon on outcomes in robotic surgery. Indian J Urol 32:204–209

Jeong W, Sammon J, Petros F, Dusik S, Rogers C (2010) V769 the role of the bedside assistant in robotic partial nephrectomy. J Urol 183:E301

Akazawa M, Lee SL, Liu WM (2019) Impact of uterine weight on robotic hysterectomy: Analysis of 500 cases in a single institute. Int J Med Robot 15:e2026. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcs.2026

Guo RX, Du JM, Wang PR et al (2020) Grading evaluation of operative complications and analysis of related risk factors in patients with stage I endometrial cancer treated by robotic-assisted and traditional laparoscopic surgery. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 55:112–119. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-567X.2020.02.010

Kim MH, Chung H, Kim WJ, Kim MM (2018) Effects of Surgical Assistant’s Level of Resident Training on Surgical Treatment of Intermittent Exotropia: Operation Time and Surgical Outcomes. Korean J Ophthalmol 32:59–64. https://doi.org/10.3341/kjo.2017.0059

Kim YW, Min BS, Kim NK et al (2010) The impact of incorporating of a novice assistant into a laparoscopic team on operative outcomes in laparoscopic sigmoidectomy: a prospective study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 20:36–41

Mitsinikos E, Abdelsayed GA, Bider Z et al (2017) Does the level of assistant experience impact operative outcomes for robot-assisted partial nephrectomy? J Endourol 31:38–42. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2016.0508

Johal J, Dodd A (2017) Physician extenders on surgical services: a systemic review Can J Surg 60:172–178 doi: 10.1503%2Fcjs.001516

Hepp SL, Suter E, Nagy D, Knorren T, Bergman JW (2017) Utilizing the physician assistant role: case study in an upper-extremity orthopedic surgical program. Can J Surg 60:115–121 doi: 10.1503%2Fcjs.002716

Blitzer D, Stephens EH, Tchantchaleishvilli V et al (2019) Risks and rewards of advanced practice providers in cardiothoracic surgery training: national survey. Ann Thorac Surg 107:597–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.08.035

Althausen PK, Shannon S, Owens B et al (2016) Impact of hospital-employed physician assistants on a level II community-based orthopaedic trauma system. J Orthop Trauma 30(Suppl 5):S40–S44. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.bot.0000510721.23126.48

Swanton AR, Alzubaidi AN, Han Y, Nepple KG, Erickson BA (2017) Trends in operating room assistance for major urologic surgical procedures: an increasing role for advanced practice providers. Urology 106:76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2017.05.007

Lenihan JP Jr, Kovanda C, Seshadri-Kreaden U (2008) What is the learning curve for robotic assisted gynecologic surgery? J Minim Invasive Gynecol 15:589–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2008.06.015

Tang FH, Tsai EM (2017) Learning curve analysis of different stages of robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy. Biomed Res Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1827913

Woelk JL, Casiano ER, Weaver AL, Gostout BS, Trabuco EC, Gebhart JB (2013) The learning curve of robotic hysterectomy. Obst Gynecol 121:87–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31827a029e

Cheng H, Clymer JW, Chen BP-H, Sadeghirad B, Ferko NC, Cameron CG, Hinoul P (2018) Prolonged operative duration is associated with complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Surg Res 229:134–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.03.022

Mahdi H, Goodrich S, Lockhart D, DeBernardo R, Moslemi-Kebria M (2014) Predictors of surgical site infection in women undergoing hysterectomy for benign gynecologic disease: a multicenter analysis using the national surgical quality improvement program data. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 21:901–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2014.04.003

Brachman PS, Dan BB, Haley RW, Hooton TM, Garner JS, Allen JR (1980) Nosocomial surgical infections: incidence and cost. Surg Clin North Am 60:15–25

Perencevich EN, Sands KE, Cosgrove SE et al (2003) Health and economic impact of surgical site infections diagnosed after hospital discharge. Emerg Infect Dis 9:196–203

Childers CP, Maggard-Gibbons M (2018) Understanding costs of care in the operating room. JAMA Surg 153:e176233. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.6233

Macario A (2010) What does one minute of operating room time cost? J Clin Anesth 22:223–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2010.02.003

Timmermans MJ, van der Brink GT, van Hught AJ et al (2017) The involvement of physician assistants in inpatient care in hospitals in the Netherlands: a cost-effectiveness analysis. BMJ Open 7:e016405. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016405

Cawley JF, Hooker RS (2013) Physician assistants in American medicine: the half-century mark. Am J Manag Care 19:e333–e341

Bohm ER, Dunbar M, itman D, Rhule C, Araneta J, (2010) Experience with physician assistants in a Canadian arthroplasty program. Can J Surg 53:103–108

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Lindsey K Leggett, Olga Muldoon, David L Howard, and Lynn D Kowalski declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. This research study was conducted retrospectively from data obtained for clinical purposes. We consulted extensively with the IRB of Touro University Nevada and due to the nature of the retrospective design, informed consent was not obtained prior to data collection. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Touro University Nevada (9/19/2019–TUNIRB000078).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leggett, L.K., Muldoon, O., Howard, D.L. et al. A comparison of surgical outcomes among robotic cases performed with an employed surgical assist versus a second surgeon as the assist. J Robotic Surg 16, 229–233 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-021-01230-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-021-01230-7