Abstract

Money demand stability is a crucial issue for monetary policy efficacy, and it is particularly endangered when substantial changes occur in the monetary system. By implementing the ARDL technique, this study intends to estimate the impact of money demand determinants in Italy over a long period (1861–2011) and to investigate the stability of the estimated relations. We show that instability cannot be excluded when a standard money demand function is estimated, irrespectively of the use of M1 or M2. Then, we argue that the reason for possible instability resides in the omission of relevant variables, as we show that a fully stable demand for narrow money (M1) can be obtained from an augmented money demand function involving real exchange rate and its volatility as additional explanatory variables. These results also allow us to argue that narrower monetary aggregates should be employed in order to obtain a stable estimated relation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The function of the demand for money is one of the most investigated macroeconomic relations. This large interest derives from the fact that stability of money demand plays a crucial role in the conduct of monetary policy and it also reflects the importance attributed to money demand stability in theoretical modelling.

As stated by Milton Friedman: «the quantity theory is in the first instance a theory of the demand for money», and the «quantity theorists accepted the empirical hypothesis that the demand for money is highly stable» (Friedman 1969, pp. 98, 108). Friedman’s statements imply that there is a stable demand function that is a stable relationship between income, price level, relative rates of return, and money demand.

Moreover, the stability of money demand represents a fundamental assumption to adopt monetary targeting. Central banks can implement monetary manoeuvres on the basis of the estimated relations between money demand and its determinants; then, a stable money demand function is considered as a necessary condition for the use of monetary aggregates in the conduct of monetary policy. In the presence of an unstable function, it is not possible, in fact, to postulate a constant conditional model for money demand.

Poole (1970) argues that in the presence of an unstable money demand, the target of monetary policy should be the interest rate. Following this reasoning, many central banks switched from monetary aggregates to the interest rate as their target in the 1970s, when money instability increased sharply. However, regardless of the monetary instrument, money still plays an important role in the formulation of an efficient policy strategy, because money demand instability implies an unstable money multiplier, preventing any possibility of forecasting the effects of monetary policies.

In this paper we study money demand in Italy in the period 1861–2011 by investigating both its determinants and its stability. Italy represents an interesting case because its monetary system has undergone several economic, social, and institutional changes (Fratianni and Spinelli 1997). For a century and a half, Italy has had different monetary regimes, has adhered to diverse exchange rate systems, and has experienced changes in the financial regulation framework. These are all factors that can influence the demand for money (Boughton 1992). In addition, in this long period, the country has experienced twelve banking crises, as well as several financial turmoils and episodes of high inflation (De Bonis and Silvestrini 2014).

The stability of money demand in Italy has been analysed in other studies (see, for instance, Thornton 1998; Caruso 2006; Muscatelli and Spinelli 1996, 2000). With respect to the existing literature, the present paper examines a longer period that covers all the relevant changes occurred in the Italian monetary policy regime and financial system, including a decade of the euro circulation. In order to do so, we reconstruct the time series for two monetary aggregates (M1 and M2), inflation, real effective exchange rate (REEX) and exchange rate volatility, by merging different existing series and by means of our own calculations. The reconstructed series are then used together with the existing series for GDP and short-term interest rate, allowing us to cover such a long period of time with an extensive analysis of money demand determinants. The empirical analysis is conducted by using the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) methodology in order to differentiate between long- and short-run effects on money demand by its determinants. Then, we investigate the stability of the estimated relations by means of the CUSUM and CUSUM of squares tests. The analysis is performed on M2, which is the standard aggregate considered to measure money demand, but also focuses on the narrow money aggregate, M1, in order to isolate money demand from other portfolio choices. We adopt two different money demand equations. Firstly, money demand is analysed with the GDP, inflation, and short-term interest rate as its determinants. Secondly, we augment this specification by including REEX and its variability as additional explanatory variables.

Our results show that instability cannot be excluded when a standard money demand function is estimated for Italy, irrespectively of the use of M1 or M2 as proxies. Furthermore, we demonstrate that despite the fact that the period of multiple banks of issue (from 1861 to 1893) seems to be characterised by a stable money demand in Italy, the period of development of the banking and financial system (from the beginning of the century till the 1930s), characterised by the strong shift from coins to paper money and bank deposits, and the following sharp increase in price levels and World War I, present an unstable money demand till up the end of the World War II (1945). Then, we argue that the reason for possible instability resides in omission of relevant variables. This allows us to show that fully stable demand for narrow money (M1) in Italy can be obtained with an augmented money demand function, involving REEX and its volatility as additional explanatory variables. As the same does not apply to the estimation of M2, we also conclude that narrower monetary aggregate should be employed as the proxy for money demand in order to obtain stable estimated relations.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 highlights the main historical events in monetary regimes and policies that potentially could have affected the demand for money in Italy. Section 3 synthesises the main results in the literature related to our analysis. Section 4 describes the methodologies employed and reports the main results obtained. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2 Money demand in Italy in a historical perspective

2.1 The first period: multiple banks of issue

The Italian unification proceeded through the annexation and acquisition of the pre-unification states by the small Kingdom of Sardinia. In 1861 the Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed, even though national unification was not completed yet. Then, the Papal State was annexed in 1870, while Friuli, Alto Adige, and Istria were incorporated only after the World War I. The new Italian Kingdom inherited the monetary and banking systems from old constituent states; therefore, the political unification posed the complex problem of the monetary and financial unification (Toniolo et al. 2003; Pecorari 2015). In 1861 it was decreed the legal tender of the Piedmontese silver lira—renamed Italian lira—and established an exchange ratio for the old currencies that were still in circulation. The adopted model, analogous to the French one, was based on bimetallism, with a fixed rate between gold and silver at 1/15.5, and convertibility of paper notes in metal coins. The first fundamental law for the monetary and financial unification, enacted in 1862, created a single currency (the Italian lira) that substituted the old moneys. Furthermore, a single coinage system was put in place (Giordano 2011; Toniolo 2011). In 1865, Italy, Belgium, France, and Switzerland signed an agreement to form the Latin Monetary Union, joined by Greece in 1868. The main economic objectives pursued by the agreement were the elimination of conversion costs in foreign exchange transactions and the reduction of international reserves. Given the characteristics of the Latin Monetary Union, however, these objectives were not achieved (Fratianni and Spinelli 1997).

The banknotes issuance remained fragmented, as the banks of issue operating in the pre-unitarian states maintained their right to issue. In the period 1861–1870, in the Kingdom of Italy, five banks of issue operated: the Banca Nazionale degli Stati Sardi;Footnote 1 the Banca Nazionale Toscana; the Banca Toscana di Credito; the Banco di Napoli; and the Banco di Sicilia. Then, from 1870 to 1893 the banks of issue were six, as the Banca Romana joined the other five (Canovai 1911; Cardarelli 1990). This period, in which multiple banks of issue operated, is of particular theoretical interest: the Italian experience has been, in fact, considered as an example of a competitive system on money issuance (Gianfreda and Janson 2001).

Competition among banks of issue does not imply in itself a problem of monetary control, even though, in the case of Italy, the regime of competition was blamed for the financial crises of 1866 and 1893. The high Italian foreign debt, the increasing public debt, and the imminent war against Austria were the main causes of the 1866 financial turmoil. In order to finance the war, on the 1 May 1866, the Government by a decree required the Banca Nazionale nel Regno to provide the Treasury with a loan of 250 million liras and in return, suspended the convertibility of its banknotes (corso forzoso) (Canovai 1911; Gigliobianco and Giordano 2012). The gold and silver coins, still widely in use, were hoarded and disappeared from circulation, while paper money began to spread among the population. The 1866 decree introduced a fundamental asymmetry between the Banca Nazionale nel Regno and the other banks of issue. Only the Banca Nazionale emitted fiat money, while the banknotes issued by other institutions could be redeemed into notes of the Banca Nazionale. Since these last ones became monetary base, there was an increase in overall money circulation (Gianfreda and Mattesini 2015). In 1893, a deep economic and financial crisis culminated in the liquidation of the two main commercial banks, in the bankruptcy of others, and in the liquidation of the Banca Romana, involved in a political and financial scandal (Pecorari 2015). In the same year, the Bank of Italy was created with the merger of the two Tuscany Banks of issue and the Banca Nazionale. Although the Banco di Napoli and the Banco di Sicilia maintained their issue rights up till 1926, the Bank of Italy became the central bank of the country.

Figure 1 illustrates the money circulation and bank deposits from 1861 to 1915. We see how, at the time of unification, money stock was largely composed by metal coins that represented 90 % of total money in circulation. Paper notes started to gain wider acceptance only after 1866 when Italy exited from the gold standard. Nevertheless, as shown by Fig. 1, metal coins circulation remained significant until the First World War, when the issuance of paper notes notably increased. Analogously, at the time of unification, the value of banks deposits was negligible. Banks deposits increased as banking system grew significantly in the Italian regions, acquiring confidence among people. In brief, as the financial and banking systems evolved, the composition of money progressively shifted from coins to paper money and bank deposits (Fratianni and Spinelli 1984, 1997).

Before the World War I, the convertibility of paper money into gold was maintained in the following periods: 1861–1866; 1882–1885; 1902–1914. In the period 1861–1893, the competition among note issuers worked well. In particular, despite the legislative interventions aimed at favouring the Banca Nazionale nel Regno and the suspension of convertibility of its notes between 1866 and 1874, competition acted as a discipline device on the dominant bank (Gianfreda and Mattesini 2015). In the gold standard adherence periods, convertibility acted as a discipline for monetary issue. In other periods, the Government exerted its control with policies that imposed limits in the issue of paper money and in minimum reserve ratios. In addition, the Government controlled the official discount rate of the banks of issue. This system, however, did not avoid the situation when the limits of issuance of bank notes were exceeded, partially due the fact that banks of issue were at the same time commercial banks (Muscatelli and Spinelli 2000). After the World War I, Italy returned to the gold standard in the period 1927–1930.

2.2 From the 1930s onwards

Similar to other countries, also Italy was affected by the Great Depression. Between 1929 and 1932, the industrial output fell by 25.1 %. Given the tight interrelationships between banks and industry, the slump had an immediate impact on the banking sector that became illiquid, threatening the stability of both the financial system and the real economy (Toniolo 1995; Gigliobianco and Giordano 2012). The Government intervened and defined a new regulatory framework. In 1933, the holding companies were permanently separated from the parent banks and their assets were taken over by the newly created state holding, the Istituto di Ricostruzione Industriale (IRI). The new Banking Act of 1936, a legislation that remained in force until 1993, profoundly reformed the banking system. Firstly, the Bank of Italy was defined as a public institution, and deposit-taking and credit activities were considered public services. Secondly, the credit system was modernised thanks to the separation between long-term and short-term credit that distinguished commercial banks from industrial banks. The supervision of the system was then concentrated in the Inspectorate for the defence of savings and the exercise of credit, chaired by the Governor of the Bank of Italy, but directed by a ministerial committee led by the Prime Minister. In this way, the 1936 banking system sanctioned the primacy of politics over banking (Fratianni and Spinelli 1997).

The banking regulation of 1936 remained fundamentally unchanged up till the 1980s and succeeded in supporting the growth of the Italian economy (Battilossi et al. 2013). It is noteworthy that the banking system improved its allocation efficiency and became much more stable. Out of the 12 banking crises identified by Reinhart and Rogoff (2009) that occurred in Italy since 1861, ten episodes occurred before 1936 and, precisely, in 1866, 1868, 1887, 1891, 1893, 1907, 1914, 1921–1922, 1930–1931, and 1935.Footnote 2 After the World War II, fixed exchange rates were maintained in the context of the Bretton Woods agreements. The 1950s and the 1960s were characterised by strong economic growth and low inflation. In the 1970s, the end of the Bretton Woods system, oil shocks, and the development of welfare state created a pressure towards accommodative monetary policies not compatible with price stability (Fratianni 2011). The main goals of monetary policy were to stabilise the interest rate and to facilitate the financing of public deficits. Only towards the end of that decade, the Bank of Italy began paying attention to the monetary aggregates and gaining independence from fiscal policy. As a result, monetary policy became less accommodative than before (Tabellini 1988). In 1979, Italy adhered to the exchange rate mechanism (ERM) of the European Monetary System. Monetary policy independence from the fiscal authority, whose need was firstly posed by the Governor of the Bank of Italy Paolo Baffi in the 1975, was reached in 1981 with the ‘divorce’ of the Bank of Italy from the Treasury (Favero and Spinelli 1999). It implied that the Bank of Italy was not obliged anymore to be a residual buyer at the Government’s bonds auctions.

A significant change concerning monetary control was the switch to M2 as an intermediate target in 1984. It resulted from the intention of the Bank of Italy to target long-run objectives and to increase its focus on price stability. The anchoring of the lira within the ERM, despite the necessity of seven realignments of the national currency, served as a monetary policy intermediate objective, meant to discipline expectations and to start the lengthy process of building up the anti-inflationary credibility of policy makers (Sarcinelli 1995). The ERM was abandoned in 1992 due to unsustainable speculative attacks on the Italian lira. The exit of Italy from the ERM required a change in monetary policy in order to avoid a spiral between exchange rate devaluation and inflation. The Bank of Italy thus began to include a direct precise reference to inflation in its objectives (Gaiotti and Secchi 2012). In the same year, another step towards the central bank independence was taken, as the Treasury was no longer allowed to borrow from the Bank of Italy. Moreover, the power to modify the discount rate, previously officially belonging to the Treasury, in 1992 was formally assigned to the Bank of Italy, sanctioning de jure independence. In sum, the 1980s and the 1990s marked a change in the monetary regime. Not only the correlation between public deficits and money creation disappeared but also the regulatory framework underwent significant changes (Gaiotti and Secchi 2012). In November 1996, the Italian currency rejoined the ERM thanks to the introduction of a broader exchange rate band in August 1993.

The lira was the official currency till the end of 2001, as starting from 2002 the euro was adopted and the ECB became the issuing institution and the reference monetary policy institution for all the members of the eurozone.

Fratianni and Spinelli (1997, 2001) argue that the monetary policy decisions in Italy fundamentally responded to the strategy pursued by the fiscal authorities. In their view, fiscal dominance was the prevailing feature of the Italian monetary history from 1861 till the 1990s. The dependence of the Bank of Italy on the Treasury had the effect of keeping low interest rates in order to reduce the costs of financing budget deficits. Consequently, interest rate targeting rather than monetary aggregates targeting was the main operative strategy of monetary policy. In this view, Italian inflation would be mainly explained by endogeneity of monetary policy to fiscal policy. The hypothesis of fiscal dominance has been supported by Favero and Spinelli (1999) and Fratianni and Spinelli (2001). These studies showed how the influence of public finance on monetary policy, already evident in the nineteenth century, became stronger after 1936, as the Bank of Italy lost degrees of independence and the Fascist Government asserted the right to unconditional central bank financing. Fiscal dominance persisted also after the World War II and increased during the 1970s, when a significant correlation between budget deficits, Treasury financing, and monetary base creation existed. Independence, gained with the divorce of the Bank of Italy and the Treasury, was definitely achieved in 1993 when the Maastricht Treaty, entering into force, imposed drastic cuts to the budget deficits and abolished all residual forms of direct financing of the Treasury.

The evolution of the circulation of money, as a percentage of GDP is illustrated in Fig. 2a. The ratio between money in circulation and GDP rapidly increased after 1861 and then declined, reaching two peaks: in 1919 and in 1944. From 1950 onwards the ratio switched in a range of 5–10 %. Figure 2b shows the pattern of bank and postal deposits as a percentage of GDP. At the time of Italian unification, money held in the form of bank deposits was negligible. However, banks deposits increased steadily till 1934 and then dramatically fell up till 1947. Subsequently, deposits increased, reaching a peak in 1978. During the 1980s and 1990s the ratio deposits on GDP declined, increasing again after 2001.

Figure 3a illustrates the trend of price index, in logarithms, from 1861 to 2011. Prices were relatively stable from 1861 until the World War I that is during the period of the gold standard. Two main upward changes in the price levels occurred during the two World Wars, with the notable exception of the deflation in 1927–1933, and in the 1970s. Figure 3b displays the inflation rate given by the first difference of the logarithm of the price index. Evident is the stationarity of inflation around the mean during the international gold standard, the sustained inflation of the World War I, the subsequent phase of deflation, the dramatic increase during the World War II and, after a period of stability, the upswing of the 1970s, and the decline of the following decades.

3 Related literature

According to economic theory, empirical analyses are generally carried out assuming that money demand is a function of a scale variable and a vector of opportunity costs. This is related to the fact that the demand for real money is intended to be determined by speculative and transaction motives. Therefore, a basic representation of the long-run money demand can be summarised by the following function:

Equation (1) represents real money demand (M/P) as a function of income (Y), of the opportunity cost (OC),Footnote 3 and of other possible explanatory variables (Z). Economic theory suggests that income should have a positive effect on money holdings. Instead, since by definition the opportunity cost variables measure the earnings from alternative assets, they should have a negative impact on money demand.

Many studies have tried to estimate money demand functions in Italy trying to take into account its major institutional and economic changes. As a result, the existing literature proposes different and sometimes contrasting evidences. Muscatelli and Spinelli (1996), with a single equation estimation based on annual data covering the period 1861–1990, are able to detect one cointegrating relation and to estimate a stable demand for money for the entire period. The same result is obtained by Sarno (1999). Following the same approach, Angelini et al. (1993) estimate a money demand function in Italy for the samples 1975–1979 and 1983–1991, and they find M2 to be stable. Thornton (1998) estimates a stable long-run money demand function in Italy over the period 1861–1980, by using the Johansen procedure of cointegration that indicates a unique long-run demand function for currency and the broad money supply. Finally, Muscatelli and Spinelli (2000) show how money demand in Italy remained relatively stable notwithstanding the multiple changes in monetary regimes in the period 1861–1996.

Still, Dooley and Spinelli (1989) raise the issue of stability as a problem for Italian money demand and this study has been followed by an extensive body of literature focusing on money demand stability (see Muscatelli and Spinelli 1997; Juselius 1998; Bagliano et al. 1992). Different methodologies and results are also presented by Gennari (1999), Bagliano (1996), Rinaldi and Tedeschi (1996), and Bagliano and Favero (1992). According to Muscatelli and Papi (1990) money demand instability in Italy can be based in the late changes in the financial system occurred between the 1970s and 1990s. The demand for money in relationship with stock market fluctuations, in the period 1913–2003, is examined by Caruso (2006). He shows that the estimated long-run relations are unstable. Juselius (1998) attributes these difficulties in the estimation of money demand in Italy to financial innovations and changes in the exchange rate mechanism in 1983. Also Carstensen et al. (2009) present an estimated money demand for Italy that is not stable over large part of a sample spanning the period 1979–2004.

Therefore, the existing literature does not completely agree on the characteristics of money demand in Italy. The mixed results may be due to a variety of factors. These include differences in sample periods, estimation techniques, and in the measures adopted for the relevant variables. Contributions that fail to identify stable money demand relations may also suffer from the problem of omitted variables. The omission of a relevant determinant, such as the effective exchange rate, could explain the inability to identify a stable money demand function (Lee and Chung 1995; Bahmani-Oskooee and Shabsigh 1996).

Mundell (1963) is the first arguing that the exchange rate should be considered as another determinant of the demand for money. Starting from this intuition, there have been several studies adopting a measure for the exchange rate in the analysis of money demand (see for instance Dreger et al. 2007; Bahmani-Oskooee and Rhee 1994; Traa 1991; Leventakis 1993; McNown and Wallace 1992; Chowdhury 1995). Nevertheless, there is no clear empirical evidence of the link between exchange rate variations and money demand. Some studies show negative coefficients (Rao et al. 2009; Dobnik 2013), while other positive ones (see, for instance, Narayan et al. 2009). These results reflect the theoretical intuition that the reaction of money demand to exchange rate variations depends on the magnitude of two different effects: (1) the wealth effect; (2) the expectation/substitution effect. The former implies that a depreciation of domestic currency raises the domestic currency value of foreign assets held by domestic residents, which could determine an increase in the demand for money because it can be perceived as an increase in wealth (see Arango and Nadiri 1981). According to the latter effect, if a depreciation of domestic currency results in an increase in expectations of further depreciation, the public may decide to hold more foreign currency and less domestic money (see Bahmani-Oskooee 1996; Bahmani-Oskooee and Pourheydarian 1990). Thus, rather than raising the demand for money, a depreciation could result in a decrease in the demand for domestic currency. Moreover, since exchange rate volatility could make the wealth effect or expectation effect uncertain, it could also have a direct impact on money demand and should, therefore, be considered as another determinant to be included in the demand for money (see Bahmani and Bahmani-Oskooee 2012; Mcgibany and Nourzad 1995; Bahmani 2013).

Applications to the Italian case are minimal in the literature. Ewing and Payne (1999) investigate the incorporation of the exchange rate into the demand for narrow money equation in several countries including also Italy, but they suggest that income and interest rate are sufficient for the formulation of a long-run stable demand for money in Italy. Capasso and Napolitano (2012) focus on money demand in Italy, but the sample adopted in their paper is considerably shorter than the one adopted in our study. Furthermore, we also include a measure for exchange rate variability in our money demand.

By focusing on long-term money stability in Italy, the present study provides some empirical evidence in order to contribute to this debate, facilitated by recent development in Italian data availability. To this aim we use also an annual data set provided by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) in the special series on the 150th anniversary of the unity of Italy. These exceptionally long series of data allow to test the stability of money demand throughout the changes that happened in monetary policy. Such changes have occurred along the entire sample under examination, and they could have affected money demand and other monetary aggregates. Among others, our objective is to fill this gap and to provide a valid empirical model which can account for the stability of money demand in Italy and work as a viable tool for policy execution.

4 Empirical analysis

Our empirical analysis on money demand in Italy relies on Eq. (1) as a general reference. It is performed by adopting both M2 and M1 as proxies for money demand. In order to estimate money demand and to test for its stability, we conduct our analysis by means of ARDL estimations and by employing measures related to income, prices, interest rates, and exchange rates as explanatory variables. Our methodological choice relies on the fact that error correction models and cointegration have been jointly applied to determine the features of money demand both in the short-run and in the long-run. Nevertheless, these analyses require a long pre-testing procedure and a reasonable large sample of data. Since our data set spans a very long period of time, we avoid the latter problem. Moreover, by applying the ARDL approach to cointegration, we circumvent the most common problems connected with stationarity because this methodology can be applied regardless of whether the variables are I(0) or I(1). The ARDL approach consists first in estimating a general distributed lag model in order to pinpoint potential structural breaks and to establish the suitable significant lags in the variables. Then, it requires the specification of an error correction model which disentangles long-run dynamics from short-run disturbances (see Pesaran et al. 2001).

4.1 Data

Our analysis is based on yearly data and spans the period 1861–2011. Based on different definitions of monetary aggregates, there have been several reconstructions of the M1 and M2 time series in Italy along the years. Therefore, in reconstructing the series of monetary aggregates, our aim was to produce homogeneous time series along the entire period studied. Hence, we identified a ‘base’ definition that is a compromise between the different definitions of monetary aggregates that have occurred in Italy over time.

It should be noted that the construction of real monetary aggregates in Italy dates back to the early 1970s and the publication of the data for the aggregate M1 started in 1983. The oldest reconstructed series available by the Bank of Italy for M1 and M2 start in 1936. Therefore, there is a gap between the beginning of the new Italian Kingdom and the first official data obtainable. In order to fill this gap we use different sources like De Mattia (1967) (for the period 1861–1889) and De Bonis et al. (2012) for coins and notes in circulation, postal current accounts, and deposits. Due to the lack of information, we reconstruct the first period of the two series using coins and notes in circulation plus banks and postal current accounts for M1, while for M2 we add to M1 deposits and postal interest-bearing deposits. In 1985 there was a first review of the statistics on monetary aggregates in Italy. A note in Banca d’Italia (1985) clarifies the criteria used to define the tools that make up the new variables, M1 and M2, and provides a clear definition of the holding sector. At the end of 1990 there was a second revision of the aggregates that remained valid until the end of 1998 when, with the start of the third stage of economic and monetary union, the definition of monetary aggregates passed under the responsibility of the Council of the European Central Bank. The reconstruction of national accounts was a project managed by the Banca d’Italia, ISTAT, and the University of Rome ‘Tor Vergata’ and coordinated by Baffigi.Footnote 4 It covered the 150-year period following the political unification of Italy. In this paper we employ the new GDP series at current prices in millions of euros reconstructed in this project.

De Bonis et al. (2012) provide data on short-term interest rate. The consumer price index for blue- and white-collar workers households (using as a year base 1913 = 1) is a variable reconstructed with data provided by the Direzione generale del lavoro (until 1925) and ISTAT (afterwards). For the series of REEX, we collected the series of the real exchange rate (REX) provided by Di Nino et al. (2011) and the series of REEX provided by Ciocca and Ulizzi (1990) till 1970, by Finicelli et al. (2005) till 2005 extended after till 2009. REEX series was then completed with data till 2011 provided by the Bank of Italy. However, there was still the problem of the lack of data during the two World Wars. In particular, there was a missing value in 1919 and 13 missing values from 1938 till 1950 in the REEX series. Our approach was based on an intuitive analysis. We first checked the correlation between REX and REEX for the entire available series. We found a high correlation index of 0.9422. Hence, we calculated the rate of change of REX and applied this to the REEX series in order to fill the gaps of the missing observations. We also employed the series of REEX to construct a variable measuring the volatility of the exchange rate by means of a GARCH(1, 1).

We employ these reconstructed series in order to perform our empirical analysis.

4.2 Money demand equations

We follow the existing literature and model the demand for money according to Eq. (1) as a function of GDP (Y t ), which measures the level of economic activity and underlines the transaction purpose for holding money, and as a function of the short-term interest rate (R t ) and inflation (P t ), which influence the opportunity cost for holding money and allow to consider the speculative motive. Concerning money demand, we decided to measure it using alternatively M1 and M2. In this way we are also able to analyse whether the stability of money demand is influenced by the type of monetary aggregate chosen.

Our reference money demand equation is the following:

where i can be 1 or 2 in order to indicate M 1,t and M 2,t , respectively; the coefficients α1 and α2 represent the elasticities of money demand with respect to income and interest rate, while α 3 is the semi-elasticity of money demand with respect to inflation.

However, the baseline money demand equation (2) can be augmented by extending the number of variables. We decided to do this with two other variables that measure the rate of currency depreciation/appreciation and its volatility. Considering the first one, we adopt REEX and for the second additional variable we use a measure of exchange rate volatility as it could make the wealth effect or the expectation effect uncertain and have a direct impact on money demand. Therefore, we consider it as another determinant to be included in the money demand function. Thus, we augment Eq. (2) as follows:

where VEX t is the additional variable measuring the volatility of REEX calculated from a GARCH(1, 1) model. Thanks to the augmented money demand equation (3) we test whether both REEX and its volatility could affect the demand for money and should therefore be included in the money demand function.

4.3 Empirical results

In implementing our empirical analysis we follow several steps. Firstly, we need to exclude that the variables considered are I(2) because the ARDL cannot be employed under this circumstance. The results from Table 1 show that none of the variables considered is integrated of order 2; therefore, we can proceed to the next step in which we explore the presence of breaks in the data.

To this aim we run basic OLS regressions of Eq. (2) with M1 and M2 in sequence as dependent variables and use the recursive residual test to investigate the presence of breaks in the series and the corresponding number of dummies. The results are shown in Fig. 4, where recursive residuals are plotted jointly with the zero line ±2 SEs.

The test identifies one impulse dummy for M1 (corresponding to the Second World War) and two impulse dummies for M2 (corresponding to the two World Wars). The Chow test for structural breakpoints in the sample of Eq. (2) confirms that these breaks are significant and decisively rejects the null hypothesis of no structural change for both M1 and M2 (see Table 2, panel A).

So far we have derived the structural breaks on the basis of the information obtained from regressing Eq. (2). Since, as shown in Table 1, some of the employed time series are non-stationary, the estimation results could simply be misleading due to spurious regressions. Therefore, the identification of structural breaks in the data requires additional evidence in order to guarantee its robustness. As the Chow test requires the predetermination of the possible breaks, we also employ the Bai and Perron (2003) test for multiple unknown breakpoints. We test the null of no structural change against an unknown number of breaks by employing an F statistic. The bottom panel of Table 2 displays two structural changes, in 1942 for M1 and in 1943 for M2. Therefore, the results of the Bai–Perron test are consistent with the results obtained from the Chow test. Once detected the presence of breakpoints in the data and constructed the dummies in order to correct for the parameters instability, we turn to the investigation of the long-run and short-run relations between money demand and its determinants in Italy. To this aim, we estimate an ARDL equation and specify the error correction model for Eqs. (2) and (3). It will allow us to assess whether there is a long-run relation between money demand and its explicative variables and then to evaluate its stability.

4.3.1 Baseline money demand estimations

Based on the model in Eq. (2), we need a dynamic specification which allows us to explain the long-run relations, but it is also able to represent the short-run dynamics in money demand. Therefore, we specify an ARDL model of Eq. (2) in which the coexistence of level and difference variables allows for studying the short-run and long-run relations in the demand for money. Thus, we assume an ARDL dynamic specification of the form:

where lnM i,t is the monetary aggregate M1 or M2 (both in logarithms) at time t. X t is the vector of explanatory variables, namely: (1) income, lnY t ; (2) interest rate, lnR t ; (3) inflation, P t . D 42 is a dummy variable associated with the Second World War incorporating the statistically significant structural breaks from 1942 to 1947. The long-run multipliers for the determinants of money demand are given by the vector of θ coefficients, while γ j represents the vectors of short-run dynamic coefficients, p and q represent the order of the underlying ARDL model, and μ t are white noise errors. We determine the proper lag length for each variable in Eq. (4) by applying SBC.Footnote 5 Before proceeding with bounds test we have to test for the goodness of fit of the ARDL specification (stability, heteroscedasticity, residuals correlation, and normality). All the specifications employed pass these tests, whose results are added in the tables reporting the results of the ARDL estimations.

Subsequently, we turn to the investigation of the long-run and short-run effects of GDP, interest rate, and inflation on money demand. As a first step in order to detect long-run multipliers and to test for their significance we employ an F test on the null hypothesis that the coefficients on the level variables are all jointly equal to zero (Pesaran and Shin 1999; Pesaran et al. 2001). The F statistic is basically a bounds test on the ARDL error correction model. This test does not rely on the conventional critical values, but it involves two asymptotic critical value bounds. The critical bounds depend on the degree of integration of the variables: I(0), I(1), or a mixture of the two. The critical values for the test are provided by Pesaran et al. (2001). In the case when the calculated test statistic lies above the upper bound, it implies that there is a long-run relation between the variables. When the test statistic lies within the bounds, no conclusion can be drawn without knowledge of the time series properties of the variables. In this case, standard methods of testing would have to be applied. No long-run relations exist when the test statistic is below the lower bound. We estimate the model in Eq. (4), based on the baseline money demand equation (2), and compute the F test for the null hypothesis \(\theta = 0,\) under the alternative hypotheses that there is a long-run level relationship between the aforementioned variables. The bounds test results are reported in Table 3. The null hypothesis of no long-run relationship is rejected since the F statistic lies above the 0.10 upper bound.

Tables 4 and 5 present the empirical results obtained from the ARDL estimation (4) of the baseline demand equation (2) for M1 and M2, respectively. Both regressions fit reasonably well and pass the main diagnostic tests. A key assumption for the ARDL methodology is that the residuals must be serially independent. The test statistics in Tables 4 and 5 show that, due to the absence of serial correlation, we can rely on our ARDL estimations. The results for both monetary aggregates are in line with theoretical expectations: in the long-run all the components influence money demand with the expected sign. In particular, almost all level estimates (Tables 4, 5, sections 2) are highly significant and have also the expected signs.

Compared to the existing literature, the estimated income elasticity for M1 and M2 is above 1 and differs from the results of Harb (2004) and Kumar et al. (2013), since their estimated income elasticities are below 1 for different groups of countries. However, our results are in line with estimated income elasticities in Capasso and Napolitano (2012) and Muscatelli and Spinelli (2000) for Italy, as well as Dreger et al. (2007) and Hamori and Hamori (2008) for a large group of countries. The estimated interest rate elasticity shows the coefficient with correct negative sign and is also statistically significant at 0.05 for M2, while for M1 the sign is correct but not significant. It is worth noticing that the estimated interest rate elasticity is negative in the great majority of the existing literature. Concerning previous studies on Italy, our results on interest rate elasticities are similar to the ones reported in Sarno (1999) and Muscatelli and Spinelli (1996).

The sign of the estimated coefficient for inflation is also in line with what theory predicts. In both monetary aggregates, M1 and M2, the estimates of the semi-elasticity of money demand with respect to inflation are negative and significant (−0.07376 and −0.076636, respectively). These results are consistent with previous studies on Italy (see, for instance, Capasso and Napolitano 2012; Muscatelli and Spinelli 1996), but the estimated coefficients result to be smaller when compared with previous studies on other countries. Dreger and Wolters (2010), for instance, find the inflation semi-elasticity to be above 4, which is a very large value in comparison with our estimations of the inflation coefficient for M1 and M2.

The results from the estimations for the short-run (Tables 4, 5, sections 1) show the complex dynamics that seem to exist between changes in money demand and changes in the fundamental variables. Most of the estimated short-run coefficients are statistically significant and have the expected sign. The estimated equilibrium correction coefficients (ECM) are −0.0172 for M1 and −0.0207 for M2 and are statistically significant at 0.01 and 0.05 with the correct sign. This implies that a deviation from the long-run equilibrium, following a short-run shock, is corrected by about 1.7 % after 1 year for M1 and the adjustment process will be at 2 % after 1 year for M2. Finally, Tables 4 and 5 (sections 2) show the results of the dummies used. Dummy ‘42 is statistically significant at 0.01 and 0.05 levels for M1 and M2, respectively. Overall, our results are consistent with the main empirical literature regarding Italy and other developed countries.

As a final step of our analysis, we evaluate the stability of the estimated money demand. Firstly, we test whether the estimated ARDL model of Tables 4 and 5 is stable by checking that all of the inverse roots of the characteristic equation associated with their models lie inside the unit circle. The results in Fig. 5 show that the stability condition is satisfied, since the inverted roots are all strictly inside the unit circle.

Secondly, we perform a formal parameter stability analysis for the ARDL representation by employing the procedure developed by Brown et al. (1975) (see also Pesaran and Pesaran 1997). Brown et al. (1975) stability test technique, CUSUM and CUSUM of squares tests, is based on the recursive regression residuals. The stability test is conducted by employing the cumulative sum of recursive residuals (CUSUM) and the cumulative sum of squares of recursive residuals (CUSUMSQ). Examining the prediction error of the model is another way of ascertaining the reliability of the modified ARDL model. If the error or the difference between the real observation and the forecast is infinitesimal, then the model can be regarded as best fitting.

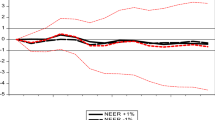

The CUSUM and CUSUMSQ statistics are updated recursively and plotted against the break points of the model. It can be assumed that the estimated coefficients are stable when the plot of these statistics lies inside the critical bounds of 5 % significance. These tests are usually implemented and interpreted thanks to a graphical representation and allow us also to evaluate the stability along the years in the sample covered. In Fig. 6a, c we plot the cumulative sums together with the 5 % critical lines.

CUSUM and CUSUM of squares tests on Eq. (2). a M1 cumulative sum of recursive residuals. b M1 cumulative sum of squares of recursive residuals. c M2 cumulative sum of recursive residuals. d M2 cumulative sum of squares of recursive residuals. The straight lines represent critical bounds at 5 % significance level

The movement inside the critical lines for both M1 and M2 is suggestive of parameters stability. Nevertheless, the two CUSUMSQ (Fig. 6b, d) are not always within the 5 % significance lines, suggesting that the residuals variance cannot be defined as stable. These results confirm our argument that the banks issue competition (from 1861 to 1893) did not imply, in itself, a problem of monetary control and stability in Italy. On the contrary, referring to Figs. 1 and 6, we can see that the money demand instability period starts together with the Italian banking systems evolution (from the beginning of the century till the 1930s), in which the composition of money started shifting from coins to paper money and bank deposits. These evolutions and novelties, together with sharply increasing prices (see Fig. 3a), seem to have reduced the stability of the estimated relations. As also evidenced by the structural breaks test, the World War I also contributed to money instability. Therefore, based on the baseline money demand equation (2), we cannot exclude that money demand in Italy has been unstable.

4.3.2 Augmented money demand estimations

A common practice in the literature on money demand is to augment the basic equation in order to look for more stable relations, as instability can be due to relevant omitted variables (see, for instance, Nautz and Rondorf 2011; Foresti and Napolitano 2013). Therefore, we augment our baseline money demand (2) and re-estimate it according to Eq. (3). The specification diagnostics in Tables 7 and 8 show values of D–W statistic closer to two, indicating no autocorrelation. Overall, the additional tests statistics performed for serial correlation, normality of residuals, functional form misspecification, and heteroscedasticity show no problems in all of them. The bounds test results are reported in Table 6, and they show that also in this case, the null hypothesis of no long-run relationship is rejected since the F statistic lies above the 0.10 upper bound. Then, we perform the ARDL estimation of the augmented money demand equation (3), by means of the specification (4). In this case X t is still the vector of explanatory variables, but it is now composed by: (1) income, lnY t ; (2) interest rate, lnR t ; (3) inflation, P t ; (4) real effective exchange rate, lnREEX t ; (5) volatility of REEX, VEX t , respectively.

The ARDL estimations of the augmented money demand equation (3) for both M1 and M2 are in line with the estimated parameters from the baseline specification (2), but it is worth noticing that the augmented estimation provides a lower elasticity with respect to income (see Tables 7, 8). Both REEX and VEX coefficients are statistically significant. This implies that the inclusion of the exchange rate, and its variability, as additional variables should be taken into account when modelling money demand in Italy. Concerning M1, the long-run estimated coefficient for REEX is −0.42129. Therefore, an increase in REEX generates a reduction in the demand for money. The same kind of effect is generated by an increase in the variability of the exchange rate, as in this case the estimated impact of VEX on M1 is negative and equal to −1.75606. Similar results are obtained for M2. In this case, the impact of VEX is considerably higher and this should be due to the fact that this monetary aggregate is substantially wider and contains elements that are more sensible to the exchange rate variation. Moreover, the negative sign for the coefficient of REEX implies that the expectation/substitution effect dominates the wealth effect in Italy.

The most important result from the estimation of the augmented money demand is related to its stability performance. The output displayed in Fig. 7 suggests that, according to a preliminary analysis, the stability of the estimated ARDL is satisfied, as all the inverse roots lie inside the unit circle.

In Fig. 8 the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests highlight a clear improvement in terms of stability of the estimated relations when compared to Fig. 6. The CUSUM confirms full stability for both M1 and M2. Nevertheless, in this case stability can also be confirmed for M1 according to CUSUMSQ test. In case of M2, CUSUMSQ highlights possible instability of the relation in the period 1970–1998. The instability of money demand in Italy for the period 1970–1990 is a recurrent result in the literature (see Muscatelli and Papi 1990). With reference to M2, this can be explained by the sudden increase in money demand for bank deposits before the 1970s, as the Italian banking system evolved substantially, and by the introduction in the 1970s of the new types of borrowing instruments by the monetary authorities. The latter involved a shift in portfolio preferences by the private sector which can make money demand less stable via exchange rate variations. Another interesting element of this result is that our estimated instability terminates in correspondence with the adoption of the euro, in which the strong reduction in the exchange rate risk has probably played a crucial role captured by our augmented money demand equation. This result also partially confirms the evidence reported in some recent studies of a stable money demand in the eurozone (see Dreger and Wolters 2010). We can thus conclude that the estimated money demand equation with the inclusion of REEX and its variability for M1 is the one that can be confidently defined as stable. This confirms the evidence in the literature that narrower monetary aggregates perform better in terms of stability (see Foresti and Napolitano 2014).

CUSUM and CUSUM of squares tests on Eq. (3). a M1 cumulative sum of recursive residuals. b M1 cumulative sum of squares of recursive residuals. c M2 cumulative sum of recursive residuals. d M2 cumulative sum of squares of recursive residuals. The straight lines represent critical bounds at 5% significance level

5 Conclusions

In the 150 years since national unification, Italy has had a notable process of economic development. In a century and a half of its history, Italy’s monetary regime changed, the banking and financial systems evolved becoming more and more complex, while the country adhered to different exchange rates systems and experienced banking crises, financial turmoils, and high inflation periods, as well as shifts in monetary policy arrangements. The first novelty of this paper is related to the fact that we have been able to cover this entire period, based on the longest time series adopted in the literature so far. In order to do so, we have reconstructed the time series for two monetary aggregates (M1 and M2), inflation, real effective exchange rate, and exchange rate volatility by merging different existing series and by means of our own calculations.

The reconstructed series have been used together with the existing series for GDP and short-term interest rate allowing us to cover such a long period of time with an extensive analysis of money demand determinants. Second, by employing the ARDL estimations, bounds, CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests, we have contributed to the literature of money demand stability in Italy by showing that these profound changes could have affected it and that in order to obtain a stable relation some adjustments are required. We have shown that instability cannot be excluded when a standard money demand function is estimated, irrespectively of the use of M1 or M2 as proxies for money demand in Italy. The estimation based on a standard money demand function has highlighted that the period of multiple banks of issue (from 1861 to 1893) seems to be characterised by a stable money demand in Italy. Then, the estimated relations become unstable in the beginning of the century, with the great development of the banking and financial system, till up the end of the World War II (1945).

Subsequently, we have demonstrated that the reason for possible instability resided in the omission of relevant variables. We have shown that a fully stable demand for narrow money (M1) can be obtained from an augmented money demand function, involving the exchange rate and its volatility as explanatory variables. The same cannot apply to the estimation of M2. On the basis of these results we have argued that narrower monetary aggregates should be employed as the proxy for money demand in order to obtain stable estimated relations and also that estimated unstable money demand can be the result of omitted variables.

Notes

In 1867, the Banca Nazionale degli Stati Sardi took the name of Banca Nazionale nel Regno d’Italia.

The other crises occurred in 1990–1995 and 2008. In their analysis of the Italian financial crises, De Bonis and Silvestrini (2014) show how episodes of financial distress often reflected previous credit development; 8 out of 12 banking crises were anticipated or accompanied by the acceleration in the credit-to-GDP-Gap.

See Golinelli and Pastorello (2002) for a survey of the literature estimating similar money demand equations.

A very large amount of methodological details about the new series are presented in Baffigi (2013).

These results can be obtained from the authors upon request.

References

Angelini P, Hendry D, Rinaldi R (1994) An econometric analysis of money demand in Italy. Temi di discussione del Servizio Studi, No. 219. Banca d’Italia, Roma

Arango S, Nadiri MS (1981) Demand for money in open economies. J Monet Econ 7:69–83

Baffigi A (2013) National accounts 1861–2011. In: Toniolo G (ed) The Oxford handbook of the Italian economy since unification. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bagliano F (1996) Money demand in a multivariate framework: a system analysis of Italian money demand in the ’80s and early ’90s. Econ Notes 25:425–464

Bagliano F, Favero C (1992) Money demand instability, expectations and policy regimes: a note on the case of Italy 1964–1986. J Bank Finance 16(2):331–349

Bagliano F, Favero C, Muscatelli VA (1992) Simultaneity and cointegration: an application to the demand for money in Italy. In: Paper presented at Banca d’Italia conference held in Perugia, Italy, March

Bahmani S (2013) Exchange rate volatility and demand for money in less developed countries. J Econ Finance 37(3):442–452

Bahmani S, Bahmani-Oskooee M (2012) Exchange rate volatility and demand for money in Iran. Int J Monet Econ Finance 5(3):268–276

Bahmani-Oskooee M (1996) The black market exchange rate and demand for money in Iran. J Macroecon 18:171–176

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Pourheydarian M (1990) Exchange rate sensitivity of the demand for money and effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policies. Appl Econ 22:1377–1384

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Rhee HJ (1994) Long-run elasticities of the demand for money in Korea: evidence from cointegration analysis. Int Econ J 8(2):83–93

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Shabsigh G (1996) The demand for money in Japan: evidence from cointegration analysis. Jpn World Econ 8:1–10

Bai J, Perron P (2003) Critical values for multiple structural change tests. Econom J 18:1–22

Banca d’Italia (1985) Bollettino Economico, n. 5. Banca d'Italia, Roma

Battilossi S, Gigliobianco A, Marinelli G (2013) Resource allocation by the banking system. In: Toniolo G (ed) The Oxford handbook of the Italian economy since unification, chap 17. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Boughton JM (1992) International comparisons of money demand. Open Econ Rev 3:323–343

Brown RL, Durbin J, Evans JM (1975) Techniques for testing the consistency of regression relationships over time. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol 37:149–163

Canovai T (1911) The banks of issue in Italy. In: National Monetary Commission, 61st Congress—Senate, Document No. 575. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

Capasso S, Napolitano O (2012) Testing for the stability of money demand in Italy: has the Euro influenced the monetary transmission mechanism? Appl Econ 44(24):3121–3133

Cardarelli S (1990) La questione bancaria in Italia dal 1860 al 1892. In: Ricerche per la storia della Banca d’Italia, vol I. Laterza, Roma-Bari, pp 105–180

Carstensen K, Hagen J, Hossfeld O, Neaves AS (2009) Money demand stability and inflation prediction in the four largest EMU countries. Scott J Polit Econ 56(1):73–93

Caruso M (2006) Stock market fluctuations and money demand in Italy, 1913–2003. Econ Notes 35(1):1–47

Chowdhury AR (1995) The demand for money in a small open economy: the case of Switzerland. Open Econ Rev 6(2):131–144

Ciocca P, Ulizzi A (1990) I tassi di cambio nominali e reali dell’Italia dall’Unità nazionale al Sistema Monetario Europeo (1861–1979). In: Ricerche per la storia della Banca d’Italia, vol I. Laterza, Roma-Bari, pp 341–368

De Bonis R, Silvestrini A (2014) The Italian financial cycle: 1861–2011. Cliometrica 8:301–334

De Bonis R, Farabullini F, Rocchelli M, Salvio A (2012) Nuove serie storiche sull’attività di banche e altre istituzioni finanziarie dal 1861 al 2011: che cosa ci dicono? QSE n. 26. Banca d’Italia, Roma

De Mattia R (1967) I bilanci degli istituti di emissione italiani dal 1845 al 1936, altre serie storiche di interesse monetario e fonte. Banca d’Italia, Rome

Di Nino V, Eichengreen B, Sbracia M (2011) Real exchange rates, trade, and growth: Italy 1861–2011. Quaderni di storia economica (Economic history working papers) no. 10. Bank of Italy, Economic Research and International Relations Area, Rome

Dobnik F (2013) Long-run money demand in OECD countries: what role do common factors play? Empir Econ 45:89–113

Dooley MP, Spinelli F (1989) The early stages of financial innovation and money demand in France and Italy. Manch Sch 57(2):107–124

Dreger C, Wolters W (2010) Investigating M3 money demand in the euro area. J Int Money Finance 29(1):111–122

Dreger C, Reimers HE, Roffia B (2007) Long-run money demand in the new EU member states with exchange rate effects. East Eur Econ 45(2):75–94

Ewing BT, Payne JE (1999) Some recent international evidence on the demand for money. Stud Econ Finance 19(2):84–107

Favero C, Spinelli F (1999) Deficits, money growth and inflation in Italy: 1875–1994. Econ Notes 28(1):43–71

Finicelli A, Liccardi A, Sbracia M (2005) A new indicator of competitiveness for Italy and the main industrial and emerging countries. Supplements to the statistical Bulletin: methodological notes, vol XV, No. 66, Bank of Italy, Rome

Foresti P, Napolitano O (2013) Modelling long-run money demand: a panel data analysis on nine developed economies. Appl Financ Econ 23(22):1707–1719

Foresti P, Napolitano O (2014) Money demand in the Eurozone: do monetary aggregates matter? Eng Econ 25(5):497–503

Fratianni M (2011) Riflessioni sulla politica economica italiana in occasione del 150ESIMO anniversario dell’Unità. MoFiR working paper no 53. Money and Finance Research group (MoFiR)—Univ. Politecnica Marche—Dept. Economic and Social Sciences, Ancona

Fratianni M, Spinelli F (1984) Italy in the gold standard period, 1861–1914. In: Bordo MD, Schwartz AJ (eds) A retrospective on the classical gold standard 1821–1931. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 405–454

Fratianni M, Spinelli F (1997) A monetary history of Italy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Fratianni M, Spinelli F (2001) Fiscal dominance and money growth in Italy: the long record. Explor Econ Hist 38:252–272

Friedman M (1969) The quantity theory of money—a restatement. In: Friedman M (ed) Studies in the quantity theory of money. University of Chicago Press, Chicago [reprinted in RW Clower (ed), Monetary Theory, Penguin Books, pp 94–111]

Gaiotti E, Secchi A (2012) Monetary policy and fiscal dominance in Italy from the early 1970s to the adoption of the euro: a review. Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers). Bank of Italy, Rome

Gennari E (1999) Estimating money demand in Italy 1970–1994. EUI WP/99/7. European University Institute, Florence

Gianfreda G, Janson N (2001) Le banche di emissione in Italia tra il 1861 e il 1893: un caso di concorrenza? Riv Polit Econ 91(1):15–74

Gianfreda G, Mattesini F (2015) Adverse clearings in a monetary system with multiple note issuers: the case of Italy (1861–1893). Cliometrica 9(1):1–25

Gigliobianco A, Giordano C (2012) Does economic theory matter in shaping banking regulation? A case-study of Italy (1861–1936). Account Econ Law 2(1):1–71

Giordano C (2011) Unificazione e modernizzazione della moneta nell’Italia dell’Ottocento. Dir Banc 150:20–25

Golinelli R, Pastorello S (2002) Modelling the demand for M3 in the euro area. Eur J Finance 8:371–401

Hamori S, Hamori N (2008) Demand for money in the euro area. Econ Syst 32(3):274–284

Harb N (2004) Money demand function: a heterogeneous panel application. Appl Econ Lett 11(9):551–555

Juselius K (1998) Changing monetary transmission mechanisms within the EU. Empir Econ 23:455–481

Kumar S, Chowdhury M, Rao BB (2013) Demand for money in the selected OECD countries: a time series panel data approach and structural breaks. Appl Econ 45(14):1767–1776

Lee TH, Chung KJ (1995) Further results on the long-run demand for money in Korea: a cointegration. Int Econ J 9(3):103–113

Leventakis JA (1993) Modelling money demand in open economies over the modern floating rate period. Appl Econ 25:1005–1012

Maddala GS, Wu S (1999) A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 61(S1):631–652

Mcgibany JM, Nourzad F (1995) Exchange rate volatility and the demand for money in the US. Int Rev Econ Finance 4(4):411–425

McNown R, Wallace MS (1992) Cointegration tests of a long-run relation between money demand and the effective exchange rate. J Int Money Finance 11(1):107–114

Mundell AR (1963) Capital mobility and stabilization policy under fixed and flexible exchange rates. Can J Econ Polit Sci 29(4):475–485

Muscatelli VA, Papi L (1990) Cointegration, financial innovation and modelling the demand for money in Italy. Manch Sch 58:242–259

Muscatelli VA, Spinelli F (1996) Modelling monetary trends in Italy using historical data: the demand for broad money 1861–1990. Econ Inq 34:579–596

Muscatelli VA, Spinelli F (1997) An econometric and historical perspective on the long-run stability of the demand for money: the case of Italy. G Econ 56(2):41–65

Muscatelli VA, Spinelli F (2000) The long-run stability of the demand for money: Italy 1861–1996. J Monet Econ 45:717–739

Narayan P, Narayan S, Mishra V (2009) Estimating money demand functions for south Asian countries. Empir Econ 36(3):685–696

Nautz D, Rondorf U (2011) The (in)stability of money demand in the euro area: lessons from a cross-country analysis. Empirica 38:539–553

Pecorari P (ed) (2015) L’Italia economica. Tempi e fenomeni del cambiamento (1861–2000). CEDAM, Milano

Pesaran HH, Pesaran B (1997) Working with Microfit. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Pesaran MH, Shin Y (1999) An autoregressive distributed lag modeling approach to cointegration analysis. In: Strom S (ed) Econometrics and economic theory in the 20th century. The Ragnar Frisch centennial symposium, chap 11. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RJ (2001) Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of levels relationships. J Appl Econom 16:289–326 [special issue in honor of J.D. Sargan on the theme “Studies in Empirical Macroeconomics”, (Eds) D. F. Hedry and M. H. Pesaran]

Poole W (1970) Optimal choice of monetary policy instruments in a simple stochastic macro model. Q J Econ 84:197–216

Rao BB, Tamazian A, Singh P (2009) Demand for money in the Asian countries: a systems GMM panel data approach and structural breaks. MPRA Paper No. 15030. University Library of Munich, Germany

Reinhart C, Rogoff KS (2009) This time is different: eight centuries of financial folly. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Rinaldi R, Tedeschi R (1996) Money demand in Italy: a system approach. Temi di Discussione del Servizio Studi, No. 267. Banca d’Italia, Rome

Sarcinelli M (1995) The Italian monetary policy in the ’80s and ’90s: the revision of the modus operandi. BNL Q Rev 195:398–422

Sarno L (1999) Adjustment costs and nonlinear dynamics in the demand for money: Italy, 1861–1991. Int J Finance Econ 4:155–177

Tabellini G (1988) Monetary and fiscal policy coordination with a high public debt. In: Giavazzi F, Spaventa L (eds) High public debt: the Italian experience. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Thornton J (1998) The long-run demand for currency and broad money in Italy, 1861–1980. Appl Econ Lett 5:157–159

Toniolo G (1995) Italian banking. In: Feinstein CH (ed) Banking, currency, and finance in Europe between the wars. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 1919–1936

Toniolo G (2011) L’unificazione monetaria dell’Italia. In: Banca d’Italia, la moneta dell’Italia unita dalla lira all’euro. Codice Edizioni, Torino, pp 3–15

Toniolo G, Conte L, Vecchi G (2003) Monetary union, institutions and financial market integration: Italy, 1862–1905. Explor Econ Hist 40:443–461

Traa BM (1991) Money demand in the Netherlands. International Monetary Fund Working Paper, No. WP/91/57. IMF, Washington, DC

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Virginia Di Nino and Massimo Sbracia from the Bank of Italy for providing us the extended data set on the exchange rates. We are also grateful to two anonymous referees who provided useful comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Daniele, V., Foresti, P. & Napolitano, O. The stability of money demand in the long-run: Italy 1861–2011. Cliometrica 11, 217–244 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-016-0143-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-016-0143-8