Abstract

Background

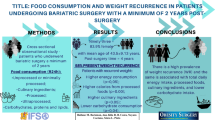

The aim of this study was to evaluate evolution of ultra-processed food intake and recurrent weight gain in patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Materials and Methods

This study is an observational longitudinal study that evaluated patients who underwent metabolic and bariatric surgery at four time points: before surgery and at 3, 12, and 60 months after surgery. Anthropometric and dietary intake data were collected through two 24-h dietary recalls. All foods consumed were classified according to degree of processing. Recurrent weight gain was considered the difference between current weight and nadir weight.

Results

The sample consisted of 58 patients with a mean age of 38.7 ± 8.9 years and 68% female. After 60 months, mean excess weight loss and recurrent weight gain were 73.6 ± 27.2% and 22.5 ± 17.4%. Calorie and macronutrient intake decreased significantly between the pre-surgery period, and 3 and 12 months post-surgery; however, there was no significant difference after 60 months. In relation to food groups or macronutrients, no difference was observed between the pre-surgery period and 60 months post-surgery. The contribution of unprocessed or minimally processed foods to calorie intake gradually decreased after 3 months post-surgery.

Conclusion

The profile of dietary intake after 60 months of metabolic and bariatric surgery tends to approach that of the pre-surgery period. The contribution of unprocessed and minimally processed foods to calorie intake decreased after 60 months, while ultra-processed food contribution increased.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lobstein T, Brinsden H, Neveux M, et al. World Obesity Atlas 2022. World Obes Fed. 2022;1–289.

Voorwinde V, Hoekstra T, Monpellier VM, et al. Five-year weight loss, physical activity, and eating style trajectories after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2022;18(7):911–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2022.03.020.

Yue TP, Mohd Yusof BN, Nor Hanipah ZB, et al. Food tolerance, nutritional status and health-related quality of life of patients with morbid obesity after bariatric surgery. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2022;48:321–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2022.01.026.

Thaler JP, Cummings DE. Hormonal and metabolic mechanisms of diabetes remission after gastrointestinal surgery. Endocrinology. 2009;150(6):2518–25. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2009-0367.

Mitchell JE, Christian NJ, Flum DR, et al. Postoperative behavioral variables and weight change 3 years after bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(8):752–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0395.

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Renata Levy, et al. NOVA. A estrela brilha. Classificação dos alimentos. Saúde Pública. World Nutr. 2016;7:28–38. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-812320182312.30872016.

Reid RER, Oparina E, Plourde H, et al. Energy intake and food habits between weight maintainers and regainers, five years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2016;77(4):195–8. https://doi.org/10.3148/cjdpr-2016-013.

Nazmi A, Tseng M, Robinson D, et al. A nutrition education intervention using NOVA is more effective than MyPlate alone: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. 2019;11(12):2965. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11122965.

Pinto SL, Silva DCG, Bressan J. Absolute and relative changes in ultra-processed food consumption and dietary antioxidants in severely obese adults 3 months after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2019;29:1810–5.

Farias G, Silva RMO, da Silva PPP, et al. Impact of dietary patterns according to NOVA food groups: 2 y after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Nutrition. 2020;74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2020.110746.

Brasil. Guia Alimentar para a População Brasileira Guia Alimentar para a População Brasileira. Ministério da Saúde, Secr. Atenção Primária à Saúde Dep. Atenção Básica, Secretaria Atenção Primária à Saúde Dep. Atenção Básica. 2ª Edição. 2014;1–156.

Jellife DB. The assessment of the nutritional status of the comunity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1966. 271 p.

World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:i–xii, 1–253.

Kamali Z, Tabesh MR, Moslehi N, et al. Dietary macronutrient composition and quality, diet quality, and eating behaviors at different times since laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2023;33(7):2158–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06651-x.

Lynch A. “When the honeymoon is over, the real work begins:” gastric bypass patients’ weight loss trajectories and dietary change experiences. Soc Sci Med. 2016;151:241–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.12.024.

Livingstone BEM, Redpath T, Naseer F, et al. Food intake following gastric bypass surgery: patients eat less but do not eat differently. J Nutr [Internet]. 2022;152:2319–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxac164.

dos Passos CM, Maia EG, Levy RB, et al. Association between the price of ultra-processed foods and obesity in Brazil. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis [Internet]. 2020;30:589–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2019.12.011.

Giusti V, Theytaz F, Di Vetta V, et al. Energy and macronutrient intake after gastric bypass for morbid obesity: a 3-y observational study focused on protein consumption. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(1):18–24. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.111732.

Moslehi N, Kamali Z, Golzarand M, et al. Association between energy and macronutrient intakes and weight change after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2023;33(3):938–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-06443-9.

Castanha CR, Ferraz ÁAB, Castanha AR, et al. Evaluation of quality of life, weight loss and comorbidities of patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2018;45(3):e1864. https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-6991e-20181864.

Noria SF, Shelby RD, Atkins KD, et al. Weight regain after bariatric surgery: scope of the problem, causes, prevention, and treatment. Curr Diab Rep. 2023;23(3):31–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-023-01498-z.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the volunteers in the research and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Stephany L. Lobão, Adler S. Oliveira: contributed in the data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final version approval. Josefina Bressan: contributed in analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final version. Sônia L. Pinto: contributed in the design of the study, data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final version approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key Points

• Patients with RYGB 60 months had an average of 22% recurrent weight gain.

• After 3 and 12 months, there was a reduction in the consumption of ultra-processed foods.

• Sixty months after, patients had a similar food intake profile to that before surgery.

• Fresh food consumption decreased and ultra-processed food consumption increased after 5 years of the RYGB.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lobão, S.L., Oliveira, A.S., Bressan, J. et al. Contribution of Ultra-Processed Foods to Weight Gain Recurrence 5 Years After Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. OBES SURG (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-024-07291-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-024-07291-5