Abstract

Background

Long-term laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) outcomes in patients with obesity are scarce. We aimed to examine the outcomes and subjective experience of patients who underwent primary LSG with long-term follow-up.

Methods

The study is a retrospective observational analysis of patients who underwent primary LSG in a single center with 5–15 years of follow-up. Patients’ hospital chart data supplemented by a detailed follow-up online questionnaire and telephone interview were evaluated.

Results

The study sample included 578 patients (67.0% female) with 8.8 ± 2.5 years of mean follow-up, with a response rate to the survey of 82.8%. Mean baseline age and body mass index (BMI) were 41.9 ± 10.6 years and 42.5 ± 5.5 kg/m2, respectively. BMI at nadir was 27.5 ± 4.9 kg/m2, corresponding to a mean excess weight loss (EWL) of 86.9 ± 22.8%. Proportion of patients with weight regain, defined as nadir ≥ 50.0% EWL, but at follow-up < 50.0% EWL, was 34.6% (n = 200) and the mean weight regain from nadir was 13.3 ± 11.1 kg. BMI and EWL at follow-up were 32.6 ± 6.4 kg/m2 and 58.9 ± 30.1%, respectively. The main reasons for weight regain given by patients included “not following guidelines,” “lack of exercise,” “subjective impression of being able to ingest larger quantities of food in a meal,” and “not meeting with the dietitian.” Resolution of obesity-related conditions at follow-up was reported for hypertension (51.7%), dyslipidemia (58.1%) and type 2 diabetes (72.2%). The majority of patients (62.3%) reported satisfaction with LSG.

Conclusions

In the long term, primary LSG was associated with satisfactory weight and health outcomes. However, weight regain was notable.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is the most frequently performed bariatric/metabolic surgery (BMS) procedure worldwide largely due to its straightforward operative technique, minimal alteration of anatomy, absence of gastrointestinal anastomoses and foreign material, successful short- and mid-term weight loss, low morbidity, and capacity for conversion to alternate BMS procedures [1,2,3,4]. Still, a paucity of long-term LSG studies with ≥ 7 years of mean follow-up has restricted the assessment of its sustained effectiveness and safety [5]. We herein present our long-term primary LSG results analyzing weight outcomes, obesity-associated disease changes, and patient satisfaction.

Patients and Methods

Analysis of a detailed online questionnaire addressing long-term LSG follow-up supplemented by hospital chart data was conducted. Inclusion criteria included patients aged 18 ≤ years old who underwent primary LSG in our center and were followed for at least 5 years after surgery. Exclusion criteria included patients who underwent another MBS after the LSG. All patients met the standard inclusion criteria for BMS (i.e., body mass index [BMI] ≥ 40.0 or ≥ 35.0 kg/m2 with weight-associated medical conditions) [6]. LSG technique has been previously described in detail [7]. Venous thromboembolic prophylaxis was initiated within 12 h of surgery and continued for 2 weeks [8]. A bariatric dietitian provided detailed dietary guidance during recovery [9]. Patients were instructed to attend routine follow-up meetings with the bariatric multidisciplinary team.

An online questionnaire containing open-ended and multiple-choice questions was administered electronically by email or SMS text and verified by a telephone interview, when needed. The questionnaire (Appendix) included information regarding weight outcomes, coexisting obesity-related conditions (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus [T2DM], obstructive sleep apnea), patient satisfaction, and reasons for weight regain. Follow-up data were obtained from the online questionnaire.

Percent excess weight loss (%EWL − ([initial weight − follow-up weight] / [initial weight − ideal body weight]) × 100) and percentage of total body weight loss (%TWL) (([initial weight − follow-up weight]/[initial weight]) × 100) were calculated. Weight regain was reported as the (1) proportion of patients that initially achieved ≥ 50% EWL at nadir, but then then fell to < 50% EWL at long-term follow-up; (2) weight gain in kilograms post nadir; (3) percentage of nadir weight; and (4) percentage of maximum weight lost. Information regarding post-LSG long-term weight loss and weight regain is presented for the whole population and for two subgroups of patients with follow-up of 5–10 years and ≥ 10 years. Patient privacy throughout the study was ensured through a password-protected de-identified participant code. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board (# 2,012,021-ASMC).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corp. Redmond, WA) and the SPSS statistical package (IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 28.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Continuous variables were presented as means ± standard deviations (SD), while dichotomous and categorical variables were presented as percentages and frequencies. Measures of change from baseline were analyzed with the dependent-samples t-test or the Wilcoxon test, as appropriate. In addition, comparisons of baseline characteristics between subgroups were calculated by Mann–Whitney U test and chi-square tests, as appropriate. To assess consistency between self-reported coexisting obesity-related conditions (i.e., diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea) with diagnoses obtained from electronic medical records, Cohen’s kappa was calculated for baseline data. The level of agreement was classified as poor (≤ 0.01), slight (0.01–0.20), fair (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), substantial (0.61–0.80), and almost perfect (0.81–1.00) [10,11,12]. All statistical tests were two-tailed and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Patient Baseline Characteristics

Of the 698 patients who were reached to participate in the study and met the inclusion criteria, 578 gave their consent and responded to the survey (response rate of 82.8%). Furthermore, 33 patients were excluded from the study analysis due to conversion to another BMS. Most of these patients converted to one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) (51.5%), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) (30.3%), and additional LSG (18.2%), while the leading reported reasons for additional MBS were weight regain (69.7%), and reflux, frequent vomiting, and eating difficulties (45.5%).

Overall, the study sample included 578 (67.0% female) patients who responded to the questionnaires, and underwent primary LSG between May 1, 2006, and December 31, 2016, in our center. Their mean pre-surgery BMI and age were 42.5 ± 5.5 kg/m2 and 41.9 ± 10.6 years, respectively. The most prevalent weight-related medical illnesses pre-surgery were dyslipidemia 43.9% (n = 254), followed by hypertension 27.7% (n = 160), T2DM 25.3% (n = 146), and obstructive sleep apnea 14.2% (n = 82). The most common additional procedure performed during primary LSG was a laparoscopic cholecystectomy (7.1%, n = 41), followed by hiatal hernia repair (6.6%, n = 38) (Table 1). The mean follow-up period was 8.8 ± 2.5 years (range: 5–14.4 years). Patients who responded to the survey had a similar pre-surgical age, BMI, and gender distribution in comparison to non-respondents (41.9 ± 10.6 vs 43.3 ± 11.9 years, p = 0.235; 42.5 ± 5.5 vs 42.9 ± 5.6 kg/m2, p = 0.463; 67 vs 70% female, p = 0.593; respectively).

Weight Outcomes

Mean nadir weight at a mean 12.8 ± 13.4 months following surgery was 77.9 ± 15.5 kg. This weight loss equated to mean nadir TWL of 34.3 ± 8.1% and mean EWL of 86.9 ± 22.8%. Overall, only 5.5% (n = 32) of primary LSG patients in our sample had insufficient weight loss (i.e., EWL < 50.0%) at nadir. Mean weight at 8.8 ± 2.5 years of follow-up was 91.3 ± 20.4 kg for the whole study population. This corresponded to a mean TWL of 23.1 ± 11.4% and mean EWL of 58.9 ± 30.1%. Significant differences between patients with 5–10 and ≥ 10 years of follow-up were found for mean weight at present (89.5 ± 19.2 vs 95.4 ± 22.5 kg, p = 0.010), and corresponding mean TWL (24.1 ± 10.6 vs 20.9 ± 12.6%, p = 0.005), and mean EWL (61.7 ± 28.4 vs 52.8 ± 32.8, p = 0.002).

The proportion of patients who reported on any weight gained from nadir was 91.7% (n = 530). The mean time interval reported between LSG and weight regain in years was 3.4 ± 2.0, and was similar between patients with different time intervals of follow-up. Mean weight regain was 13.3 ± 11.1 kg for the whole study population, while less weight regain was reported in the group with 5–10 years of follow-up in comparison to the group with ≥ 10 years of follow-up (12.2 ± 9.5 kg vs 15.6 ± 13.7, p = 0.041).

Rate of weight regain, defined as nadir ≥ 50.0% EWL, but at follow-up < 50.0% EWL was 34.6% (n = 200), while this rate was lower in the group with 5–10 years of follow-up in comparison to the group with ≥ 10 years of follow-up (n = 125 (31.3%) vs n = 75 (42.1%), p = 0.007) (Table 2).

Baseline characteristics of patients whose weight loss was successful at nadir (EWL ≥ 50%) but failed at long-term follow-up (EWL < 50%) were similar, except for higher initial weight (121.8 ± 21.0 kg) and BMI (43.6 ± 5.2 kg/m2) and lower proportion of current smoking (12.0%, n = 24) as compared to patients that succeeded both at nadir and at long-term follow-up (115.9 ± 17.6 kg, 41.3 ± 4.9 kg/m2 and 24.0% (n = 82), P = 0.002, p < 0.001, and P = 0.001, respectively).

Primary LSG patient-reported reasons for weight regain are presented in Table 3. Over half of all patients (56.8%, n = 302) with weight regain reported that they “did not follow the MBS guidelines” recommended by their health professionals after LSG. The second most frequently reported reason for regain was “lack of exercise” (51.9%, n = 276), followed by “patients’ subjective impression of being able to ingest larger quantities of food in a meal” (41.1%, n = 218), and “not meeting with a dietitian” (38.6%, n = 205). Also, weight regain due to “Covid-19 consequences” was mentioned in textual responses by some patients (1.7%, n = 9). Despite the fact that 91.7% (n = 530) reported at least some weight regain, the majority (62.3%, n = 360) were “sufficiently satisfied” with the procedure and “would choose LSG again.” Interestingly, similarity between patients with different follow-up time intervals was found with respect to of the reasons reported for weight regain (Table 3).

The questionnaire also offered possible reasons for choosing a bariatric procedure other than LSG in the future, such as “today there are more advanced procedures” (28.0%, n = 162, answered “yes” on this item) and “because I’m not satisfied with the LSG” (13.8%, n = 80, answered “yes” on this item).

Hospitalizations, Procedures, and Clinical Follow-up

Nine percent of patients (n = 52) visited the emergency room, and 12.3% (n = 71) were hospitalized at some point after primary LSG, not necessarily related to their surgery (Table 4). The majority of stated emergency room visits were related to BMS (78.8%, n = 41), with gallbladder stones reported as the most frequent cause (39%, n = 16), followed by abdominal pain, dehydration and vomiting (26.8%, n = 11), leak or necrosis (9.8%, n = 4), stenosis or stricture of the sleeve (7.3%, n = 3), bleeding (2.4%, n = 1), incisional hernia (2.4%, n = 1), iron deficiency anemia (2.4%, n = 1), and kidney stone (2.4%, n = 1).

Additional non-bariatric surgery after LSG was reported by 39.8% of patients (n = 230). Upper endoscopy was the most common invasive procedure reported (31.0%, n = 179), followed by plastic surgeries (9.7%, n = 56), cholecystectomy (9.3%, n = 54), gynecologic procedures (6.7%, n = 39), orthopedic surgeries (6.2%, n = 36), and hiatal, umbilical, and ventral hernia repair (4.0%, n = 23). About half (47.2%) of the patients reported that they suffered from heartburn or took any drugs to treat heartburn. Only a minority of patients reported routine contact with the dietitian throughout long-term follow-up (6.9%, n = 40), and 55.2% (n = 319) reported undergoing routine blood tests after LSG (Table 4).

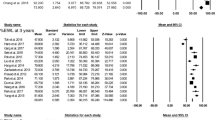

Change in Associated Medical Problems

Significant reductions from baseline in the proportion of LSG patients suffering from hypertension, dyslipidemia, and T2DM were observed (p < 0.001 for all). Rates of no change, improvement, and resolution for selected associated medical problems are depicted in Fig. 1.

Discussion

Long-term LSG Outcomes

The predominance of the LSG among other BMS procedures arose before its rates of long-term weight loss and revision were known. Until recently, ≥ 7-year mean LSG outcomes were scarce. In 2018, a meta-analysis by Clapp and colleagues [5] reported outcomes synthesized from prior studies incorporating 652 patients who completed ≥ 7 years of mean follow-up. From 2018 through 2021, several definitively long-term LSG outcome reports in patients with obesity were published (8 observational studies, 1 randomized controlled trial) [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Our current investigation studied outcomes in 578 LSG patients; to our knowledge, this is the largest single series of LSG outcomes analyzed at ≥ 8.8 years. Herein, we relate the key study findings of the current study to the aforementioned recent reports.

Weight Outcomes

The meta-analysis of studies with > 7 years of mean follow-up by Clapp et al. found that 72.2% of patients attained ≥ 50.0% EWL at follow-up. Nine other long-term studies published later also demonstrated significant sustained weight loss at their respective follow-up points. Six reported a follow-up weight loss comparable to that of the current study [13,14,15, 19, 20], although three of these studies had 3–4-year longer follow-up durations [15, 19, 20]. In three of the later studies, follow-up weight loss was markedly less than in the current study, with ≤ 50.0% total EWL: Major et al. reported on a significant 16.3 BMI-point reduction at nadir, but at 10-year follow-up EWL was 45.4% [21]; Gronroos et al.’s randomized controlled trial (RCT) reported a 47.0% EWL [17]; and Hauters et al., 42.0% EWL [18].

A study by Felsenreich and co-workers is notable for its achievement of a ≥ 15-year follow-up with 96.0% patient retention, nearly twice the follow-up duration of the current study and most of the other LSG studies [52]. The authors saw a stable 61.0% EWL at this extended endpoint, but at the cost of a high revision rate — almost half of the patients (49.1%) were converted to another procedure. The report of Fiorani et al. is also unique in the long-term LSG literature, in that, not only was there no weight regain, but weight loss continued beyond the 1-year nadir through 8 years of follow-up. This report, however, is limited by both the small initial sample size (44 patients undergoing LSG) and the high lost-to-follow-up rate of 75.0% in the LSG group [16].

Weight Regain

The cause of weight regain in LSG is multifactorial, influenced by individual physiology, dietary choices, activity level, culture, and genetics [22, 23]. In addition, assessment of BMS weight regain is not yet standardized, and there is wide variability in its reporting complicating outcome comparison [24,25,26,27]. Herein, we focused on only studies that had specifically defined and quantified weight regain.

Perhaps the most frequently used definition of weight regain in recent years is the proportion of patients that initially achieved ≥ 50.0% EWL but then regained weight to have < 50.0% EWL at follow-up. In a meta-analysis of long-term LSG data (≥ 7-year follow-up), Clapp and co-workers analyzed nine studies with respect to this measure, yielding a pooled weighted mean proportion of 27.8% (95% CI: 22.8, 32.7) with a range of 14.0–37.0% [5]. Our study had a similar sample size and follow-up period, and using this definition, weight regain was on the higher end, (34.6%) of the range reported by Clapp et al. This was because the current study’s subgroup of LSG patients with ≥ 10-year follow-up contained a significantly higher proportion of patients who regained weight (42.1%) relative to LSG patients with 5–10 years of follow-up (31.3%).

Perhaps in recognition of the arbitrary nature of the 50% EWL cutoff, other methods of assessing weight regain have been proposed (i.e., weight regain from nadir weight calculated as weight in kilograms, BMI, percentage of preoperative weight, percentage of nadir weight, and percentage of maximum weight lost). Using percentage of maximum weight lost, Capoccia et al. reported long-term weight regain results in 104 LSG patients with more than 5-year follow-up [14].

Weight regain ≥ 15.0– < 30.0% of maximum weight lost was considered mild, or > 30.0%, severe. By this classification, 25.0% and 22.0% experienced mild and severe weight regain, respectively. Using slightly different thresholds, our study reported 37.0% of patients as having experienced mild weight regain (< 25.0% of maximum weight lost), and 55.1% as having experienced significant weight regain (≥ 25.0% of maximum weight lost). The different thresholds confound the proportional comparison; however, the current study’s cohort had a mean percentage weight regain of maximum weight loss of 33.4%, slightly higher than the 31.5% reported by Capoccia et al. As should be expected, the current study’s subgroup of LSG patients with 5–10 years of follow-up, possibly a more apt comparator, had a slightly lower mean percentage weight regain of maximum weight lost than that reported by Capoccia et al. (30.8% vs 31.5%).

A final recent example of weight regain in LSG patients, calculated using yet another measure, is provided by Ben-Porat and colleagues. In their study of 212 patients, weight regain was defined as the proportion of patients regaining ≥ 15% of nadir weight [13]. According to this measure, exactly 50% of their patients were classified as experiencing weight regain. Similarly, using this definition, just over half (50.9%) of the current study’s entire cohort experienced significant weight regain (with 48.8% of LSG patients with 5–10-year follow-up experiencing weight regain vs 55.9% of patients with ≥ 10-year follow-up). In addition, weight regain from nadir weight calculated in kilograms in both studies was nearly equivalent (14.6 kg vs 13.3 kg). These comparative results parallel those of other long-term LSG patients over the long term, regardless of how they were measured and recorded (e.g., at clinical visit or by questionnaire) [28].

Resolution of Coexisting Conditions

In addition to significant and sustained weight loss, this study and most of the other LSG studies suggest that, at 7–15 years after the procedure, LSG provides meaningful resolution of obesity-related medical problems. Kraljevic et al. saw high rates of resolution in dyslipidemia (54.8%), hypertension (60.5%), and T2DM (61.0%) [20]. In the current study, good resolution of long-term coexisting conditions was found, including hypertension (51.7%), dyslipidemia (58.1%), and T2DM (72.2%). These rates were comparable to those reported by Capoccia et al. [14] and notably greater than those of Ben-Porat and Hauters, both including markedly smaller cohorts [13, 18].

In Felsenreich et al.’s study, although very few patients at baseline had any obesity-associated conditions, hypertension was resolved in 6/12 (50.0%) at ≥ 15 years of follow-up [15]. All patients in Ismail and co-worker’s cohort achieved complete resolution of hypertension, T2DM, and GERD between 6 months and 2 years but no long-term follow-up data was given [19]. Coexisting medical condition data provided in the included studies of the meta-analysis were too sparse for comparison, which is also true of other published work [16].

In Kraljevic et al., 52.0%, and in Hauters et al., 80.0% of the LSG cohort with baseline GERD experienced ongoing or worsened reflux at follow-up; of patients without preoperative reflux, 32.4% and 43.0%, respectively, developed de novo GERD in follow-up [18, 20]. While there are centers that have reported favorable mid-term LSG outcomes with respect to GERD [29, 30], the implications for complications due to both pre-existing and de novo GERD remain among the most important considerations for selection of this procedure. In the present study, about half of the patients reported that they suffered from heartburn or took any drugs to treat heartburn. However, this was reported subjectively with no available imaging test results to support it.

Patient Satisfaction and Reasons for Weight Regain

Several of the long-term LSG study comparators recorded quality of life (QoL) data using standardized assessment instruments [15, 16]. Others, as in the current study, assessed patient-reported characterization of the behaviors they believed influenced their weight regain through a questionnaire [13]. Study responses diverged in some of the parameters investigated, suggesting differing patient perspectives regarding whether maintaining a regimen of consulting with a dietitian or surgeon affected their LSG outcomes. The contrasting findings suggest the importance of further research to better clarify patient-reported experiences and behavioral choices in order to improve long-term BMS care.

Adherence to close follow-up of BMS patients is important but challenging beyond 2 years, where the rate is reported to be 40–62% [31,32,33]. We observed in the current study, as in most other BMS studies, that the rate of postoperative patient-reported dietitian interaction and routine blood testing was quite low. This finding confirmed the challenging nature of preserving interactive contact with patients over the long term. Designing studies that consider the input of patients regarding their weight regain over their years of long-term follow-up should provide insights that can be integrated into the longitudinal treatment regimen [34].

Limitations and Strengths

The major strengths of this study include the use of a large representative sample of LSG patients similar in baseline data composition to that of both a national and an international registry [35, 36]. However, there are some limitations to be acknowledged. First, data were collected mainly via a self-report questionnaire generated by the research team that has not been validated. Though it has become an acceptable method, initiated by the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions [37, 38], relying on patient-reported outcomes entails a potential for information, recall, and response bias. Nevertheless, Chao and colleagues observed in a study of 585 LSG and RYGB patients at 38 sites that patient-reported BMS outcomes had a high level of agreement with hospital records in early follow-up [39]. In this manner, to increase the validity of the data in the present study, some data were also collected by hospital charts and when needed data were verified by a telephone interview. Moreover, testing reliability of data collection is an important element of confidence in a study’s accuracy [11]. In our study, self-reported coexisting obesity-related conditions data at baseline presented fair to moderate agreement with the available data obtained from hospital records (Cohen’s kappa of 0.574, 0.559, 0.451, and 0.284 for reporting on T2DM, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and dyslipidemia [p < 0.001], respectively). Nonetheless, reporting bias for follow-up data collection should be considered.

Second, the study lacked objective measurements such as a medication list, blood test results, and imaging test results, and it lacked a validated QoL instrument. Finally, study follow-up was performed during the COVID-19 pandemic which may have affected the study results. However, weight regain due to “Covid-19 consequences” was reported by only a few patients in the present study.

Conclusions

At long-term follow-up, primary LSG was associated with satisfactory weight and health outcomes. However, weight regain was notable. More efforts should be made to increase patients’ engagement in follow-up routines in the long-term following MBS.

References

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. Bariatric Surgery Survey 2018: similarities and disparities among the 5 IFSO chapters. Obes Surg. 2021;31(5):1937–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-05207-7.

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. IFSO Worldwide Survey 2016: primary, endoluminal, and revisional procedures. Obes Surg. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3450-2.

English WJ, DeMaria EJ, Brethauer SA, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery estimation of metabolic and bariatric procedures performed in the United States in 2016. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(3):259–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2017.12.013.

Lo Menzo E, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Changing trends in bariatric surgery. Scand J Surg. 2015;104(1):18–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1457496914552344.

Clapp B, Wynn M, Martyn C, et al. Long term (7 or more years) outcomes of the sleeve gastrectomy: a meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(6):741–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2018.02.027.

NIH conference. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity Consensus Development Conference Panel. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(12):956–61.

Sakran N, Raziel A, Goitein O, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity in 3003 patients: results at a high-volume bariatric center. Obes Surg. 2016;26(9):2045–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-016-2063-x.

Telem DA, Gould J, Pesta C, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery: care pathway for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(5):742–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2017.01.027.

Sherf Dagan S, Goldenshluger A, Globus I, et al. Nutritional recommendations for adult bariatric surgery patients: clinical practice. Adv Nutr. 2017;8(2):382–94. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.116.014258.

Ranganathan P, Pramesh CS, Aggarwal R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: measures of agreement. Perspect Clin Res. 2017;8(4):187–91. https://doi.org/10.4103/picr.PICR_123_17.

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276–82.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74.

Ben-Porat T, Mashin L, Kaluti D, et al. Weight loss outcomes and lifestyle patterns following sleeve gastrectomy: an 8-year retrospective study of 212 patients. Obes Surg. 2021;31(11):4836–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05650-0.

Capoccia D, Coccia F, Guarisco G, et al. Long-term metabolic effects of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2018;28(8):2289–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3153-8.

Felsenreich DM, Artemiou E, Steinlechner K, et al. Fifteen years after sleeve gastrectomy: weight loss, remission of associated medical problems, quality of life, and conversions to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass-long-term follow-up in a multicenter study. Obes Surg. 2021;31(8):3453–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05475-x.

Fiorani C, Coles SR, Kulendran M, et al. Long-term quality of life outcomes after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass-a comparative study. Obes Surg. 2021;31(3):1376–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-05049-3.

Gronroos S, Helmio M, Juuti A, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss and quality of life at 7 years in patients with morbid obesity: the SLEEVEPASS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(2):137–46. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5666.

Hauters P, Dubart JW, Desmet J, Degolla R, Roumain M, Malvaux P. Ten-year outcomes after primary vertical sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity: a monocentric cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(12):6466–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-08137-8.

Ismail M, Nagaraj D, Rajagopal M, et al. Seven-year outcomes of laproscopic sleeve gastectomy in Indian patients with different classes of obesity. Obes Surg. 2019;29(1):191–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3506-3.

Kraljevic M, Cordasco V, Schneider R, et al. Long-term effects of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: what are the results beyond 10 years? Obes Surg. 2021;31(8):3427–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05437-3.

Major P, Stefura T, Dziurowicz B, et al. Quality of life 10 years after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2020;30(10):3675–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04726-7.

Athanasiadis DI, Martin A, Kapsampelis P, et al. Factors associated with weight regain post-bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(8):4069–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08329-w.

El Ansari W, Elhag W. Weight regain and insufficient weight loss after bariatric surgery: definitions, prevalence, mechanisms, predictors, prevention and management strategies, and knowledge gaps-a scoping review. Obes Surg. 2021;31(4):1755–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-05160-5.

Baig SJ, Priya P, Mahawar KK, Shah S, Indian Bariatric Surgery Outcome Reporting G. Weight regain after bariatric surgery-a multicentre study of 9617 patients from Indian Bariatric Surgery Outcome Reporting Group. Obes Surg. 2019;29(5):1583–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03734-6.

Brethauer SA, Kim J, El Chaar M, et al. Standardized outcomes reporting in metabolic and bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2015;25(4):587–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-1645-3.

King WC, Hinerman AS, Belle SH, et al. Comparison of the performance of common measures of weight regain after bariatric surgery for association with clinical outcomes. JAMA. 2018;320(15):1560–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14433.

Voorwinde V, Steenhuis IHM, Janssen IMC, et al. Definitions of long-term weight regain and their associations with clinical outcomes. Obes Surg. 2020;30(2):527–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-04210-x.

Oved I, Endevelt R, Mardy-Tilbor L, et al. Health status, eating, and lifestyle habits in the long term following sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2021;31(7):2979–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05336-7.

Garg H, Aggarwal S, Misra MC, et al. Mid to long term outcomes of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy in Indian population: 3–7 year results - a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2017;48:201–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.10.076.

Melissas J, Braghetto I, Molina JC, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2015;25(12):2430–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-1906-1.

Owolabi EO, Mac Quene T, Louw J, et al. Telemedicine in surgical care in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. World J Surg. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-022-06549-2.

van Erkel FM, Pet MJ, Bossink EH, et al. Experiences of patients and health care professionals on the quality of telephone follow-up care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a large qualitative study in a multidisciplinary academic setting. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3):e058361. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058361.

Chao GF, Bonham AJ, Ross R, et al. Patient-reported comorbidity assessment after bariatric surgery: a potential tool to improve longitudinal follow-up. Ann Surg. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004841.

Fried M, Hainer V, Basdevant A, et al. Interdisciplinary European guidelines for surgery for severe (morbid) obesity. Obes Surg. 2007;17(2):260–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-007-9025-2.

Israeli Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. National Center for Disease Control and Israeli Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Annual Summary 2020. https://www.health.gov.il/PublicationsFiles/Bariatric_2020.pdf

Brown W, Kow L, Shikora S, et al. Sixth IFSO Global Registry Report 2021. Henley-on-Thames: IFSO & Dendrite Clinical Systems Ltd; 2021. Available at: https://www.e-dendrite.com/IFSO6

Larjani S, Spivak I, Hao Guo M, et al. Preoperative predictors of adherence to multidisciplinary follow-up care postbariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(2):350–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2015.11.007.

Wheeler E, Prettyman A, Lenhard MJ, et al. Adherence to outpatient program postoperative appointments after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(4):515–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2008.01.013.

Aminian A, Kashyap SR, Wolski KE, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after metabolic surgery versus medical therapy for diabetes: insights from the STAMPEDE Randomized Trial. Ann Surg. 2021;274(3):524–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000005003.

Acknowledgements

We thank TW McGlennon, Medwrite, Maiden Rock, WI, USA, for statistical analysis support.

Funding

Medwrite received a grant for assistance with manuscript development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Statement of Ethics

The study protocol and all procedures of the study were approved as compliant with the ethical standards of the Assuta Medical Center (IRB #43–20-ASMC).

Written Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights

The study was performed in accord with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and subsequent amendments.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

LSG Patient Experience and Satisfaction Questionnaire

-

1.

Initials of your name and surname

-

2.

Research code number

-

3.

Age

-

4.

Family status

- Married

- Single

- Divorced

- Widower

- Other

-

5.

Current weight (in kg)

-

6.

Height (in cm)

-

7.

Are you a smoker?

- Yes

- No

- I used to smoke in the past

-

8.

What is the minimal weight you achieved since the surgery? (in kg)

-

9.

How long did it take to achieve the above weight? (in months)

-

10.

What was the duration of the weight loss since the surgery? (in months)

-

11.

Did you gain weight after the weight loss? (even if it’s few kilos)

- Yes

- No

-

12.

If yes, when did you started to gain weight? (in years)

-

13.

If you gained weight since the surgery, what did you think was the main cause? (you can choose more than one of the options)

- I didn’t eat as recommended

- The sleeve enlarged

- I didn’t exercise

- I wasn’t followed by a dietitian

- Other

-

14.

Did you have to go to the ER in the post-operative period?

- Yes.

- No.

-

15.

If yes, explain what the reason was

-

16.

Were you hospitalized in the post-operative period?

- Yes.

- No.

-

17.

If yes, explain what the reason was

-

18.

Did you undergo another bariatric surgery before the sleeve gastrectomy?**

- Yes

- No

-

19.

If yes, which surgery did you undergo?**

- LSG – laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy

- LAGB – Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding

- SRVG—Silastic ring vertical gastroplasty

-

20.

If yes, how long before the sleeve gastrectomy? (in years)**

-

21.

If yes, what was the reason to undergo the sleeve gastrectomy?**

- weight gain

- drug-resistant reflux and heartburn

- a complication such as a sleeve stenosis or a twisted sleeve

- vomiting and eating difficulties

- nutritional deficiencies

- other

-

22.

Did you undergo another surgery after the sleeve gastrectomy?**

-

23.

If yes, how long after the sleeve gastrectomy? (in years)**

-

24.

If yes, what surgery did you undergo?**

- sleeve reduction (an additional sleeve gastrectomy)

- bypass with a single anastomosis (mini-gastric bypass)

- bypass with two anastomoses (classic bypass)

- duodenal bypass with two anastomoses

- duodenal bypass with one anastomosis (SADI)

- addition of a gastric band

- other

-

25.

If yes, what was the reason to undergo another surgery?**

- weight gain.

- drug-resistant reflux and heartburn

- a complication such as a sleeve stenosis or a twisted sleeve

- vomiting and eating difficulties

- nutritional deficiencies

- other

Questions 26–29 are directed only to women

-

26.

Did you get pregnant since the surgery?

- Yes

- No

-

27.

If yes, how many times have you gotten pregnant since the surgery?

-

28.

Did you give birth after surgery?

- Yes

- No

-

29.

If yes, how many times did you give birth?

-

30.

Did you suffer from gallstones before the surgery?

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know

-

31.

If yes, what is true for you?

- I suffered from gallstones before the surgery and I underwent a cholecystectomy when I underwent the sleeve gastrectomy

- I suffered from gallstones before the surgery and I underwent a cholecystectomy after the sleeve gastrectomy

- I suffered from gallstones before the surgery and I underwent a cholecystectomy before the sleeve gastrectomy

-

32.

Were you diagnosed with gallstones since the sleeve gastrectomy?

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know

-

33.

Did you undergo a cholecystectomy since the sleeve gastrectomy?

- Yes

- No

-

34.

Did you undergo any surgery since the sleeve gastrectomy?

- Yes

- No

-

35.

If yes, explain which surgery.

-

36.

Do you suffer from heartburn or do you take any drugs to treat heartburn?

- Yes

- No

-

37.

Did you undergo a gastroscopy since the surgery?

- Yes

- No

-

38.

If yes, what were the findings?

-

39.

Are you satisfied with the surgery? Grade from 1 to 10 (1 = not satisfied at all, 10 = very satisfied)

-

40.

If you underwent another bariatric surgery, are you satisfied with the surgery? Grade from 1 to 10 (1 = not satisfied at all, 10 = very satisfied)**

-

41.

If you could choose again the type of bariatric surgery, would you choose again a sleeve gastrectomy?

- Yes

- No

-

42.

If not, why? (you can choose more than one of the options)

- today there are more advanced procedures

- because I’m not satisfied from the surgery

-

43.

Did you suffer from diabetes type 2 before the surgery? (diagnosis by medical record/taking pills to treat diabetes)

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know

-

44.

If yes, what was the treatment? (you can choose more than one of the options)

- Diet

- Drugs

- Insulin

- Drugs and insulin

- Not treated

- I don’t know

-

45.

If yes, what is true for you?

- there was an improvement

- there was a total improvement (I was cured)

- I don’t know

- there was no improvement

-

46.

Did you suffer from hypertension before the surgery?

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know

-

47.

If yes, what is true for you?

- there was an improvement

- there was a total improvement (I was cured)

- I don’t know

- there was no improvement

-

48.

Did you suffer from sleep apnea or did you use a CPAP mask while asleep?

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know

-

49.

If yes, what is true for you?

- there was an improvement

- there was a total improvement (I was cured)

- I don’t know

- there was no improvement

-

50.

Did you suffer from hyperlipidemia before the surgery? (high cholesterol/triglycerides/LDL in your blood)

-

51.

If yes, what is true for you?

- there was an improvement

- there was a total improvement (I was cured)

- I don’t know

- there was no improvement

-

52.

Were you followed by a dietitian after the surgery?

- No

- Only the first/second year after the surgery

- Intermittently during the years

- Regularly during the years, but not currently

- Regularly during the years to this day

-

53.

With which frequency did you undergo blood tests since the surgery?

-I didn’t undergo any blood test since the surgery

-I underwent blood tests only the first/second year after the surgery

-I underwent blood tests intermittently during the years

-I undergo blood tests regularly since the surgery

**These questions were asked to be marked only for patients who undergo another bariatric surgery in their past.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sakran, N., Soifer, K., Hod, K. et al. Long-term Reported Outcomes Following Primary Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. OBES SURG 33, 117–128 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-06365-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-06365-6