Abstract

Purpose

To analyze the safety of laparoscopic ventral hernia delayed repair in bariatric patients with a composite mesh.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective single-center observational trial analyzed all bariatric/obese patients with concomitant ventral hernia who underwent laparoscopic abdominal hernia repair before bariatric surgery (group A) and laparoscopic delayed repair after weight loss obtained by the bariatric procedure (group B).

Results

Group A (30 patients) had a mean BMI of 37.8 ± 5.7 kg/m2 (range: 34.0–74.2 kg/m2); group B (170 patients) had a mean BMI of 24.6 ± 4.5 kg/m2 (range 19.0–29.8 kg/m2) (p < 0.05). Mean operative time: group A, 51.7 ± 26.6 min (range 30–120); group B 38.9 ± 21.5 min (range 25–110) (p < 0.05). Average length of stay: group A, 2.0 ± 2.7 days (range 1–5) versus group B, 2.8 ± 1.9 days (range 1–4) (p > 0.5). Recurrent hernia group A 1/30 (3.3%) versus recurrent hernia group B 4/170 (2.3%) (p > 0.5). Bulging: group A, 3/30 (10.0%) versus group B, 0/170 (0%) (p = 0.23).

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates the safety of performing LDR in patient candidates for bariatric surgery in cases of a large abdominal hernia (W2–W3) with a low risk of incarceration or an asymptomatic abdominal hernia. In the case of a small abdominal hernia (W1) or strongly symptomatic abdominal hernia, repair before bariatric surgery, along with subsequent bariatric surgery and any revision of the abdominal wall surgery with weight loss, is preferable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence of incisional hernia as a complication of abdominal surgery is variously described in the literature [1, 2]: in a 2014 systematic review, over an average observational period of 23.7 months, the average rate of abdominal hernias was estimated to be 12.8% [1]. Infection of the incision will increase the rate of hernia up to 23% [3,4,5]. In 2009, the European Hernia Society (EHS) developed a classification for incisional and ventral hernias [6]. In this classification, the incisional hernias are distinguished by location (median and lateral) and by size (W1 < 4 cm; W2 4–10 cm; W3 > 10 cm). W3 incisional hernias are commonly referred to as giant incisional hernias. Enough evidence is now available that laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with an intraperitoneal onlay mesh (IPOM) is now an accepted gold standard method, with recurrence rates varying from 1.4 to 9% [7,8,9,10,11]. Similar results can be reproduced in the obese population, with recurrence rates varying from 3.0 to 8.3% with all the advantages of laparoscopic repair [12]. The debate is still open about the appropriate approach to patients presenting for bariatric surgery with a history of anterior abdominal wall defects, whether symptomatic or asymptomatic, and controversy exists about the timing of hernia repair in relation to bariatric surgery. In the presence of an incisional/abdominal hernia in a patient who has to undergo bariatric surgery, we have 3 options (Fig. 1), which are fundamentally linked to the size of the defect and to the presence or absence of specific symptoms such as pain and subocclusive episodes.

-

Option 1. If we observe the presence of a small abdominal hernia (W1) in the absence of occupation of the hernial sac or the presence of an intestinal loop engaged in the sac with the presence or absence of symptoms, due to the high risk of postoperative bowel occlusion, it is advisable to perform LCMR (laparoscopic concomitant mesh repair) or LCPRS (laparoscopic concomitant primary repair with suture) as a bridge treatment to definitive surgery involving LDR (laparoscopic deferred repair) with a mesh.

-

Option 2. In the presence of a larger abdominal hernia (W2–W3), the risk of occlusion is very low due to the size of the defect itself, so LDR is preferable.

-

Option 3. In cases of a strongly symptomatic abdominal hernia, the hernia can be treated first; then, the patient may undergo bariatric surgery.

The aim of this retrospective study was to demonstrate the safety and feasibility of the LDR technique with composite mesh positioning in obese patient candidates for bariatric surgery.

Material and Methods

This study is a retrospective analysis of a cohort of obese patients with abdominal hernia performed at a single high-volume Bariatric CoE (Centre of Excellence - certified by the Italian Society of Obesity Surgery, Società Italiana di Chirurgia dell’Obesità e delle Malattie Metaboliche SICOB). All interventions were performed at San Marco Hospital - Gruppo San Donato, Zingonia – Bergamo (Italy) from January 2002 to December 2018. We included in the analysis all obese patients who came for observation and had abdominal hernia. All patients underwent abdominal CT for proper assessment of the size of the defect and the herniated content and were evaluated for any signs of intestinal distress. All abdominal hernias were classified according to the EHS classification [6]. In all patients, the same type of prosthesis (Parietex Composite™ mesh—Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and the same type of nonabsorbable mechanical fixation (ProTack™—Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) were used with the double crown technique, and an overlap of 4–6 cm was respected. Data relating to preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative variables were analyzed. Among the intraoperative variables, the size of the defect, the characteristics of the defect, the operating time, and any intraoperative complications were analyzed. The postoperative variables analyzed included duration of postoperative hospital stay, postoperative pain (detected by visual rating score (VRS)), postoperative complications, return to normal work, and degree of patient satisfaction. Follow-up was scheduled for 10 days, 1 month, 6 months, 1 year and then annually; the incidence rates of seromas, hematomas, bulging, recurrences, and reoperations were analyzed. In the follow-up, we differentiated the recurrences from the hernias both clinically and through radiological investigation; in the last instance, laparoscopic reoperation confirmed the presence of relapse vs. bulging. All patients signed adequate informed consent.

Surgical Technique

The patient is placed in the supine position. The position of the trocars must be as far as possible from the defect by calculating an overlap of the prosthesis of at least 5 cm. The pneumoperitoneum is induced with a Veress needle that is usually introduced into the left subcostal site. In general, the trocars are arranged to draw a triangle converging towards the defect to thereby be able to reach its ends by laparoscopic instruments. First, adhesiolysis is performed to recognize the size of the hernia, separating each anterior abdominal wall adhesion and visualizing the whole laparotomy wound to assess the presence of small defects. Once the abdominal wall has been completely freed and other small defects have been identified, the hernial sac is not reduced or treated, but it is left in situ. The prosthesis of the appropriate size is therefore chosen, and it is temporarily fixed on four angular landmarks with straight needles transcutaneous to the abdominal wall. Normally, we use ProTack (ProTack™—Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) as fixation systems: a first round of ProTack is placed approximately 1 cm from the edge of the prosthesis and 3 cm from each other; a second crown of agraphes is positioned approximately 2 cm from the hernial margin on the collar (the most fibrous and hardest part) to prevent the prosthesis from sliding inside the defect. No drains are placed, and a compressive dressing is applied for 15 days. The patient will then carry an elastic band for abdominal containment for 1 month to minimize the risk of seroma.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed by entry into an Excel-type database and statistical analysis using XLStat. Categorical variables are reported as frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables are reported as medians and standard deviations (SDs). Univariate analysis of the differences between groups was performed. For all the tests used, the statistical significance level was set at the conventional p < 0.05.

Results

Our retrospective analysis of a cohort of obese patients with abdominal hernia was conducted at our center from January 2002 to December 2018. During this period, we performed 4800 bariatric surgeries. Two hundred patients had an abdominal wall hernia. In 30 patients (group A) with a BMI of 37.8 ± 5.7 kg/m2 (range 34.0–74.2 kg/m2), abdominal hernia was treated before bariatric surgery was performed. A total of 170 patients (group B) underwent surgery at a time varying from 8 months to 2 years after adequate weight loss, with an average BMI of 24.6 ± 4.5 kg/m2 (range 19.0–29.8 kg/m2). The preoperative characteristics in the two populations were homogeneous with the exception of the parameters of weight, height, BMI, and comorbidities. The average BMI of group A was 37.8 ± 5.7 kg/m2 (range 34.0–74.2 kg/m2), compared with the average BMI of group B, which was equal to 24.6 ± 4.5 kg/m2 (range 19.0–29.8 kg/m2), p < 0.05. The average age of group A was 58 ± 12 years (range 30–64 years), compared with the average group B age of 57 ± 13 years (range 27–65 years), p > 0.5. Other characteristics of the population are summarized in Table 1, including the preoperative comorbidities of the two populations.

In Table 2, we have summarized the characteristics of the primary abdominal hernia or the incisional hernia undergoing surgery, divided into the two groups: A and B. Additionally, in this case, the two populations in question were homogeneous. In group A, there were 3/30 (10%) recurrent incisional hernias; in group B, there were 23/170 (13.5%) recurrent incisional hernias. The interventions were carried out electively, with the exception of 1/30 (3%) in group A and 2/170 (1.2%) in group B. The characteristics of the abdominal hernia classified according to the EHS classification [6] and the additional intraoperative variables that were detected are shown in Table 2. Thirty patients (group A) underwent surgery before performing a bariatric operation due to the presence of a symptomatic abdominal hernia and low- or high-grade intestinal obstruction. In 20 patients with a symptomatic W1 incisional hernia, a 20 × 15 cm mesh was placed; in 15 with a defect of 8–12 cm (W2–W3), a 20 × 25 cm mesh was placed. A total of 170 patients (group B) underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy bariatric surgery. None of the patients had occlusion episodes. In 15 patients, a 37 × 28 cm prosthesis was placed; in 25 patients, a 30 × 20 cm prosthesis was placed; in 100 patients, a 25 × 20 cm prosthesis was placed; and in 30 patients, a 20 × 15 cm prosthesis was placed. In both groups, patients were treated laparoscopically. We did not record any conversion to laparotomy. The operating time was 51.7 ± 26.6 min (range 30–120 min) in group A and 38.9 ± 21.5 min (range 25–110 min) in group B (p < 0.05).

The data relating to the immediate postoperative period are shown in Table 3. We found no statistically significant difference in terms of postoperative length of stay (p > 0.5): group A, 2.0 ± 2.7 days (range 1–5 days) versus group B, 2.8 ± 1.9 days (range 1–4 days). Other comparison parameters with regard to the immediate postoperative period did not reach levels of significance; in particular, we did not find any differences in the level of complications or pain detection using VRS.

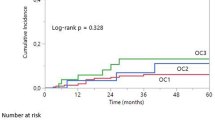

Follow-up, scheduled at 10 days, 1 month, 6 months, 1 year, and then yearly (the follow-up rates were 100%, 100%, 100%, 100%, and 98%, respectively), revealed a general rate of seromas within the first month of 4/30 (13.3%) in group A and 10/170 (5.9%) in group B (p < 0.05), without a correlation to the size of the hernia. Regarding the medium- to long-term follow-up for the relapse and bulging rate, we found 1/30 (3.3%) relapses in group A versus 4/170 (2.3%) relapses in group B, which was not statistically significant (p > 0.5). We recorded a general bulging rate in group A of 3/30 (10%) and in group B of 4/170 (0%); this result was not statistically significant but did approach the limits of significance (p = 0.23) (Table 4).

Discussion

Why should you use LDR with mesh? The reasons are many: first, the abdominal field is clean, and there is no risk of having gastric fistulas or anastomotic dehiscence deriving from the concomitant bariatric intervention, which would cause an infection of the mesh with further aggravation of the general condition of the patient, who will most likely require removal of the infected mesh. Compared to normal-weight subjects, patients with obesity have a significant increase in intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). This pressure exerts its force on the prosthesis itself with the risk of causing detachment of the mesh during normal daily activities or if the patient should have further sudden increases in this pressure, for example, due to coughing episodes or during physical exertion. If the abdominal hernia is treated when the patient has lost a significant part of the weight, it is easier to obtain good abdominal distension created by CO2 and more working space, a lower postoperative IAP, and a clear reduction in general complications related to the resolution of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and sleep apnea that can affect the results of mesh repair. Furthermore, the duration of the surgical procedure is shorter if only the bariatric procedure is performed. This avoids problems of long intubation, as venous return and tissue oxygenation can be compromised [13]. Another problem of LCMR is that as the patient loses weight, his or her abdominal wall shrinks, and similarly, the mesh can exhibit various degrees of shrinkage. The result, associated with a marked initial IAP, may be the occurrence of relapse or bulging [14]. For simple small defects (W1) with an omentum in the hernia sac, the risk of incarceration still appears minimal, and these may be left in situ: the omentum in the sac has the same effect as a “plug” and prevents bowel incarceration and obstruction. In contrast, in the presence of a small symptomatic defect (W1) or a defect with an empty hernia sac, the best strategy is LCMR, as the possibility that the patient may encounter an occlusive episode is high. Almost 36% of patients develop bowel obstruction due to incarceration without concomitant repair [15]. Small defects may be closed primarily with a suture passer. In this case, the recurrence may be as high as 25% [15]. Another study, conducted by Newcomb WL [16], examined 27 preoperative bariatric patients with complex ventral hernia repair. Seven patients underwent ventral hernia repair simultaneously, and all others were deferred. All seven patients had a recurrence, and one patient in the deferred group needed an urgent operation for incarceration [16]. Bowel obstruction is a well-documented possible sequelae of untreated hernias. Our data showed that treatment performed after bariatric surgery yielded better outcomes in terms of complications (seroma) and surgical time, and both parameters were significantly better (p < 0.05). Regarding the pain detected and the immediate postoperative course (mainly understood as duration of hospitalization), we did not find a statistical significance but only a modest decrease in Group B. Finally, with regard to medium-term to long-term follow-up values, bulging results were better in Group B, without statistical significance (p = 0.23). Patients undergoing gastric bypass can experience a high postoperative risk: incarceration and potential proximal bowel obstruction can stress the fresh anastomosis, with possible leakage that greatly endangers the patient’s life [17]. Furthermore, patients undergoing simultaneous gastric bypass and abdominal hernia repair with mesh (LCMR) may have an immediate risk of postoperative prosthetic infection related to intestinal contamination due to bacterial translocation [18] or of complications such as anastomotic fistulas. As already noted [18], concomitant use of prosthetic material to repair ventral hernias in patients undergoing an LSG procedure should be safe and feasible. Our results also confirm the literature data: in patients with severe obesity and concomitant abdominal/incisional hernia, a staged approach is recommended [19]. Our data confirm that if possible (for small, asymptomatic hernias with a low risk of intestinal obstruction), this approach is preferable. Weight loss prior to hernia repair is likely to improve hernia repair outcomes. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy can therefore be considered the intervention of choice if a patient has a large abdominal/incisional hernia (W2–W3) or the presence of a small asymptomatic hernia (W1) (Fig. 1): there is no manipulation of the intestine and no ante-colic anastomoses are created as in the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or one-anastomosis gastric bypass and sufficient omentum remains to cover the bowel. This approach yields a lower postoperative risk, a lower risk of complications at the level of the abdominal wall hernia, and a rapid weight loss, allowing quick treatment of abdominal hernia when adequate weight loss is obtained.

The main limitations of this study are that it was a single-center observational retrospective study without a control group. Another limit is represented by the different numerical sizes of the two groups.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates the safety of performing LDR in patient candidates for bariatric surgery in cases of a large abdominal hernia (W2–W3) with a low risk of incarceration or an asymptomatic abdominal hernia. In the case of a small abdominal hernia (W1) or a strongly symptomatic abdominal hernia, repair before bariatric surgery, along with subsequent bariatric surgery and any revision of the abdominal wall surgery with weight loss, is preferable. This study demonstrates that laparoscopic repair of primary and postincisional abdominal wall hernias in obese patients is a safe, effective, and reproducible procedure in obese/bariatric patients. The main limitations of this study are that it was a single-center retrospective observational study without a control group. The debate about concomitant treatment is widespread in the literature, and in our experience, we do not have enough data on this topic. However, experience requires us not to place a prosthetic net in a field potentially at risk of bacterial contamination in case of complications. It is therefore preferable to avoid concomitant treatment with prostheses due to the high risk of intra-abdominal and mesh infections.

References

Bosanquet DC, Ansell J, Abdelrahman T, et al. Systematic review and meta-regression of factors affecting midline incisional hernia rates: analysis of 14,618 patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(9) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138745.

Olmi S, Magnone S, Erba L, et al. Results of laparoscopic versus open abdominal and incisional hernia repair. JSLS. 2005;9(2):189–95.

Itatsu K, Yokoyama Y, Sugawara G, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for incisional hernia after abdominal surgery. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1439–47.

Sanchez VM, Abi-Haidar YE, Itani KM. Mesh infection in ventral incisional hernia repair: incidence, contributing factors, and treatment. Surg Infect. 2011;12:205–10.

Olmi S, Scaini A, Cesana GC, et al. Laparoscopic versus open incisional hernia repair: an open randomized controlled study. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(4):555–9.

Muysoms FE, Miserez M, Berrevoet F, et al. Classification of primary and incisional abdominal wall hernias. Hernia. 2009;13(4):407–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-009-0518-x.

Al Chalabi H, Larkin J, Mehigan B, et al. A systematic review of laparoscopic versus open abdominal incisional hernia repair, with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg. 2015;20:65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.05.050.

Olmi S, Cesana G, Sagutti L, et al. Laparoscopic incisional hernia repair with fibrin glue in select patients. JSLS. 2010;14(2):240–5. https://doi.org/10.4293/108680810X12785289144359.

Novitsky YW, Cobb WS, Kercher KW, et al. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair in obese patients: a new standard of care. Arch Surg. 2006;141(1):57–61.

Pierce RA, Spitler JA, Frisella MM, et al. Pooled data analysis of laparoscopic vs. open ventral hernia repair: 14 years of patient data accrual. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(3):378–86.

Olmi S, Cesana G, Erba L, et al. Emergency laparoscopic treatment of acute incarcerated incisional hernia. Hernia. 2009;13(6):605–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-009-0525-y.

Tsereteli Z, Pryor BA, Heniford BT, et al. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (LVHR) in morbidly obese patients. Hernia. 2008;12(3):233–8.

Paajanen H, Laine H. Operative treatment of massive ventral hernia using polypropylene mesh: a challenge for surgeon and anesthesiologist. Hernia. 2005;9(1):62–7.

Angrisani L, Lorenzo M, Cutolo PP. Incisional hernia in obese patients. In: Incisional hernia. Updates in surgery. Milano: Springer; 2008. ISBN 978-88-470-0721-5.

Eid GM, Mattar SG, Hamad G, et al. Repair of ventral hernias in morbidly obese patients undergoing laparoscopic gastric bypass should not be deferred. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(2):207–10.

Newcomb WL, Polhill JL, Chen AY, et al. Staged hernia repair preceded by gastric bypass for the treatment of morbidly obese patients with complex ventral hernias. Hernia. 2008;12(5):465–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-008-0381-1.

Jacob BP, Ramshaw B. The SAGES manual of hernia repair. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2013. ISBN 978-1-4614-4824-2

Cozacov Y, Szomstein S, Safdie FM, et al. Is the use of prosthetic mesh recommended in severely obese patients undergoing concomitant abdominal wall hernia repair and sleeve gastrectomy? J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(3):358–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.008.

Menzo EL, Hinojosa M, Carbonell A, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and American Hernia Society consensus guideline on bariatric surgery and hernia surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(9):1221–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2018.07.005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

IRB approval was not necessary. For this type of study formal consent is not required. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Olmi, S., Uccelli, M., Cesana, G.C. et al. Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair in Bariatric Patients: the Role of Defect Size and Deferred Repair. OBES SURG 30, 3905–3911 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04747-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04747-2