Abstract

Introduction

The advancement of minimal invasive techniques pushed the age limit for patients qualified for bariatric surgery.

Aim

The aim of the study was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) in a cohort of patients aged 60 years or more, compared with a group of matched controls below 40 years old.

Methods

The medical records of 856 patients were analyzed. Patients aged 60 years or older were identified as cases. Those below 40 years were identified as the controls. Cases were closely matched (1:1) with the controls by body mass index (BMI) (± 1 kg/m2) and presence or absence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

Results

A 34 matched pairs were included in the study. There was no significant difference in the median operation length. No conversion from laparoscopic to open surgery was needed. The hospital length of stay was significantly longer in the study group (4.5 ± 1.9 vs 3.9 ± 1.5 days, p = 0.047). The complication, 30-day reoperation, and 30-day reoperation rates were comparable in both groups. There were no 30-day readmissions nor 30-day mortality. ΔBMI after 12 months was significantly lower in the study group (13.56 ± 6.05 vs 10.3 ± 4.89, p = 0.008) as well as %EBMIL (50.71 ± 25.94 vs 64.20 ± 23.29, p = 0.015).

Conclusions

The study suggests that LSG is a safe method of bariatric treatment in patients aged above 60 years. Even though weight loss may be lesser than in younger patients, it can still be considered satisfactory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The continued development of medical care has significantly increased the life expectancy over the last decades. In the United States (U.S.), the life expectancy has reached a new maximum of 77.8 years. [1, 2] The prevalence of obesity in the elderly population continues to increase, with the proportion of the U.S. population aged 65 years or older predicted to rise from 12% in 2000 to 20% in 2030 [3, 4]. In elderly adults, excess weight is associated with a higher prevalence of numerous chronic health conditions and lowers the quality of life. Bariatric surgery is the most effective and permanent treatment of morbid obesity, not only weight-reducing, but also treating the obesity-related comorbidities. [5] The effectiveness of the bariatric surgery has led to a significant increase of its popularity, especially of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Along with the advancement of minimal invasive techniques, the age limit for patients qualified to bariatric operations constantly increases, presently exceeding 60 years [6,7,8,9]. Despite evident clinical benefit of bariatric surgical treatment, the question of the cut-off age remains unanswered, as the risk of perioperative morbidity and mortality is an important issue with the bariatric patients.

Aim

The aim of the study was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) in a cohort of patients aged 60 years or more, compared with a group of matched controls below 40 years old.

Methods

Study Design

The medical records of 856 patients were analyzed. All patients underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as a primary bariatric procedure between January 2013 and March 2017 in a single bariatric center (over 300 laparoscopic bariatric procedures annually). The patients were qualified for the operation using standard criteria, established in 1991 by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). [10] The LSG technique was described in previous publications. [11,12,13] Patients aged 60 years or older were identified as cases. Four hundred and eighteen patients below 40 years were identified as the controls. The cases were matched with the controls by body mass index (BMI) (± 1 kg/m2) and presence or absence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus. A control subject was selected for each patient aged 60 years or above using algorithm described by Kawabata (1:1 matching procedure) [14]. Only cases with suitable matching control subjects were included in the study. The cutoff of 60 years of age was chosen as this age represents the United Nations standard criterion for older population. Follow-up of both cases and controls was performed with a telephone survey, which included questions about postoperative weight 12 and 24 months after the procedure. Telephone surveys are less expensive and time-consuming for both interviewers and interviewees, with similar or even higher response rates than face-to-face interviews. Remission of comorbidities, occurrence of heartburn sensation, and compliance characterized as dietary treatment, regular physical effort, and psychological professional help use were another questions asked. The outcomes of interest were mortality, 30-day readmission, 30-day reoperation, operation length, length of hospital stay (LOS), weight loss, and comorbidity improvement. We selected diabetes mellitus and hypertension to follow because those comorbidities were the most prevalent components of the metabolic syndrome in our material. Diabetes improvement was defined as absence or reduction of antidiabetic drugs or insulin use. Hypertension improvement was defined as normal blood pressure values (≤ 140/90 mmHg) and absence or reduction of antihypertensive drug use. Weight loss was presented as the percentage of excess BMI loss (%EBMIL) and the change in BMI (ΔBMI).

Bias

Data was collected with a telephone survey performed by single investigator—thus, there is a risk of recall bias. To minimize selection bias, a large number of cases of primary LSG (867) were analyzed. As there are over 800 LSGs performed yearly in Poland according to the national reports [15, 16], our data is representative. All patients underwent the same procedure according to a standard surgical technique of LSG, what eliminates referral bias. Study size was determined by the number of patients aged 60 years or above matched with controls.

Statistical Methods

Analysis was performed using SAS® software, University Edition (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The paired t test or Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to analyze continuous outcomes. Dichotomous outcomes were analyzed using McNemar’s test or Fisher’s exact test. Breslow and Day description was used to analyze matched (dependent) and unmatched (independent) data. [17].

Results

Baseline Characteristic

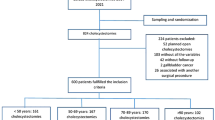

A total of 856 patients underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy from January 2013 to March 2017. Fifty-seven patients were identified as cases and were matched with controls. There were no patients who refused to answer questions or participate in the study. However, in case of 23 pairs, we failed to contact at least one patient due to invalid phone numbers or out of date information (Fig. 1). Out of remaining 34 pairs, the mean age was 63.3 years (range: 60–68) in the study group and 30.9 years (range: 24–39) in the control group. The mean preoperative BMI was 46.8 kg/m3 (± 6.6) in the elderly group and 46.7 kg/m3 (± 6.8) in the control group (p = 0.202). Fifty-three percent patients were female and 47% were male in the study group with 50% and 50% accordingly in the control group. Demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Surgical Safety

There were no significant differences in the median operation length between the elderly (82.1 ± 28.0 min) and younger patients (77.2 ± 25.7 min, p = 0.687). No conversion from laparoscopic to open surgery was needed in either group. The postoperative hospital length of stay (LOS) was significantly longer in the study group (4.5 ± 1.9 days) than in the control group (3.9 ± 1.5 days, p = 0.047). The complication rate was comparable in both groups. Two cases of bleeding and one case of rhabdomyolysis occurred in the elderly group compared to one case of bleeding and one case of rhabdomyolysis in the control group. Reoperation was necessary in all cases of postoperative bleeding. Therefore, the 30-day reoperation rate was 5.9% in the study group versus 2.9% in the control group (p = 0.564). There were no 30-day readmissions nor 30-day mortality. However, one patient out of the study group, who had experienced rhabdomyolysis, died within 90 days after the surgery due to respiratory failure (Table 2).

Weight Loss

The mean postoperative BMI 12 months after surgery was significantly higher in the study group (36.38 kg/m3 ± 7.07 vs 33.10 kg/m3 ± 5.65, p = 0.004). ΔBMI after 12 months was significantly lower in the study group (13.56 ± 6.05 vs 10.3 ± 4.89, p = 0.008) as well as %EBMIL (50.71 ± 25.94 vs 64.20 ± 23.29, p = 0.015). The mean BMI 24 months after the surgery was also higher in elderly group with no statistical significance (32.57 ± 9.45 versus 30.16 ± 4.8, p = 0.081). The difference in the mean ΔBMI and %EBMIL 24 months after the surgery presented no statistical significance, respectively: 14.34 ± 8.22 vs 16.51 ± 5.97 (p = 0.125) and 69.92 ± 45.91 vs 77.50 ± 19.41 (p = 0.112) (Table 3).

Comorbidity Improvement

There was no significant difference observed in the course of type 2 diabetes nor hypertension between the groups. However, a trend toward higher rate of diabetes improvement was observed in the study group (29.4% vs 17.7%, p = 0.127) at 12 months. A rate of hypertension improvement was comparable in both groups (64.7% vs 64.7%, p = 0.346) (Table 4).

Discussion

With the increasing prevalence of obesity and longer life expectancy, the rate of elderly population qualifying to bariatric treatment is rising [18, 19]. The efficacy of bariatric surgery, considering improvement in the comorbidity course, daily functioning and quality of life has already been established. [20,21,22,23] Despite benefits of bariatric surgery, there are serious concerns about the perioperative safety of the elderly population, who may have a higher anesthesia-related perioperative risk, also influenced by a higher prevalence of comorbidities. [6] Preliminary data on bariatric surgery in elderly patients reveal controversial results. A study by Livingston et al. [24] (n = 25,428) from 2006 suggested that bariatric surgery in older patients was associated with more postoperative complications. The authors recommended limiting bariatric surgery to patients younger than 65 years old. Similarly, Gebhart et al. [18] presented a significantly lower rate of in-hospital mortality in patients aged between 18 and 60 years old compared to above 60 years old (0.05 vs. 0.11%). Reduction in perioperative morbidity associated with laparoscopic minimally invasive approach [25] as well as improved long-term outcomes have led to the increasing popularity of the bariatric surgery [23].

Our study showed comparable rate of complications both in elderly and younger groups of patients. We observed neither cases of 30-day readmission nor 30-day mortality. Our results correspond to those by Navarrete et al. [19]. In the retrospective analysis of 206 cases, the complication rate was similar to our research and no mortality was observed However, the interpretation of the results regarding mortality should be cautious. Most authors reported 30-day mortality or did not state the period of observation. In our study, the mortality reported within 30-day observation period was non-existent; however, one elder patient died after the analysis period of 30. This patient was diagnosed with postoperative rhabdomyolysis. We suggest that in the future, the minimal mortality observation period should be minimum 90 days, which will be essential to enclose the fatal cases subsequent to the perioperative complications.

In our study, the elderly cohort experienced lower weight loss compared with the control group. There are few publications investigating the relationship between age and weight loss outcomes. Pequignot et al. [7] recently demonstrated the safety and efficacy of sleeve gastrectomy for patients aged above 60 years. In their study, 84 patients aged > 60 years old were matched with 42 patients aged less than 60 years old. The mean %EWL was significantly lower in the elderly group after 12 months (56.2% versus 71.4%, P < .01) and 24 months (51.8% versus 73.5%, P < .01). Similar results were presented by Navarrete et al., [19] with the elderly cohort having experienced lower weight loss compared with the younger group after a 3-year follow-up.

One of the important issues analyzed in our study was the rate of improvement of the obesity-related comorbidities comparable between both groups. We focus on diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Those conditions are the most prevalent components of the metabolic syndrome in bariatric population and have potentially severe medical and socioeconomic effects on everyday life.

Our findings are in correlation with the studies by Peter et al. [26] from 2005 and Dunkle-Blatter et al. [27] from 2006, who showed greater weight loss in younger patients, but a greater reduction in medication use in older patients, with similar complication rate and mortality in both groups. A report by Leivonen et al. [28] showed that comorbidity remission rate after 12 months was similar in older and younger patients. Positive influence of bariatric surgery on the course of the comorbidities seems not to be affected by age and comorbidity improvement should be considered as the major benefit from bariatric surgery for the elderly patients.

The present study has several limitations related to its retrospective analysis and small study group. Most significantly, the limited sample size reduces the accuracy of assessment of the complication rate and comorbidity course after the surgery. Another limitation of the study is the risk of selection bias due to inability to contact each patient who underwent LSG. Additionally, the follow-up survey was performed with a telephone questionnaire, therefore may be affected by recall bias. Another limitation is a high rate of lost to follow-up, which resulted from the lack of possibility to contact patients due to invalid phone numbers recorded in the patients’ charts or out of date information.

The safety of LSG was the most important subject of our analysis. As shown in the study, 30-day mortality may not be sufficient and extension of the observation period should be recommended in the future studies. Unfortunately, the information on the obesity-related comorbidities other than diabetes and hypertension (e.g., dyslipidemia and reflux disorder) was not available from our database. Additionally, the data on some underappreciated issues in older adults (e.g., changes in quality of life and functional capacity) was incomplete.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is a safe and effective method of bariatric treatment in patients aged above 60 years. The complication and morbidity rate is comparable between elderly and younger patients. Meticulous preoperative examination and comprehensive medical evaluation allow to provide an optimal outcome. Even though weight loss may be lesser than in younger patients, it can still be considered satisfactory.

The short-term follow-up showed similar improvement in comorbidities. Therefore, age might not be considered as a single contraindication to bariatric surgery and LSG should be included in the treatment options of the elderly obese population.

References

Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the united states, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–45.

Arias E, Rostron BL, Tejada-Vera B. Division of Vital Statistics Abstract, Betzaida National Vital Statistics Reports United States Life Tables, 2005. 2010; 58.

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among us adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–41.

Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, et al. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289:76–9.

Tucker ON, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Indications for Sleeve Gastrectomy as a Primary Procedure for Weight Loss in the Morbidly Obese. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:662–7.

Ramirez A, Roy M, Hidalgo JE, et al. Outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients >70 years old. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;8:458–62.

Pequignot A, Prevot F, Dhahri A, et al. Is sleeve gastrectomy still contraindicated for patients aged Z 60 years? A case-matched study with 24 months of follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;11:1008–13.

van Rutte PW, Smulders JF, de Zoete JP, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy in older obese patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2014–9.

Ritz P, Topart P, Benchetrit S, et al. Benefits and risks of bariatric surgery in patients aged more than 60 years. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2013.12.012.

Gastrointestinal Surgery for Severe Obesity. NIH Consens Statement. 1991;9(1):1–20.

Janik MR, Rogula T, Kowalewski PK, et al. Case-Control Study of Postoperative Blood Pressure in Patients with Hemorrhagic Complications after Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy and Matched Controls. Obes Surg. 2017;27(7):1849–53.

Kowalewski PK, Olszewski R, Walędziak MS, et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy- a Single-Center, Retrospective Study. Obes Surg. 2018;28(1):130–4.

Janik MR, Walędziak M, Brągoszewski J, et al. Prediction Model for Hemorrhagic Complications after Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: Development of SLEEVE BLEED Calculator. Obes Surg. 2017; Apr;27(4):968–72.

Kawabata H, Tran M, Hines P, et al. Using SAS to Match Cases for Case Control Studies. Pap. 173–29. Princeton, New Jersey; p. 1–7.

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. Bariatric Surgery Worldwide 2013. Obes Surg. 2015;25(10):1822–32.

Janik MR, Stanowski E, Paśnik K. Present status of bariatric surgery in Poland. Wideochirurgia I Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2016;11:22–5.

Breslow NE, Day NE. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Statistical methods in cancer research volume I-the analysis of case-control studies. Stat Methods. Cancer Res. 1980;1:346.

Gebhart A, Young MT, Nguyen NT. Bariatric surgery in the elderly: 2009–2013. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(2):393–8.

Navarrete A, Corcelles R, Del Gobbo GD, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy in the elderly: A case-control study with long-term follow-up of 3 years. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;13:575–80.

Janik MR, Rogula T, Bielecka I, et al. Quality of life and bariatric surgery: cross-sectional study and analysis of factors influencing outcome. Obes Surg. 2016;26(12):2849–55.

Major P, Matłok M, Pędziwiatr M, et al. Quality of Life After Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1703–10.

Janik MR, Bielecka I, Kwiatkowski A, et al. Cross-sectional study of male sexual function in bariatric patients. Videosurgery and Other Miniinvasive Techniques. 2016;11(3):171–7.

Colquitt J, Pickett K, Loveman E, et al. Surgery for weight loss in adults (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;8(8):CD003641.

Livingston EH, Huerta S, Arthur D, et al. Male gender is a predictor of morbidity and age a predictor of mortality for patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery. Ann Surg. 2002;236:576–82.

Hanipah ZN, Punchai S, Karas LA, et al. The Outcome of Bariatric Surgery in Patients Aged 75 years and Older. Obes Surg. 2018;28(6):1498–503.

Peter SDS, Craft RO, Tiede JL, et al. Impact of Advanced Age on Weight Loss and Health Benefits After Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass. Arch Surg. 2005;140(2):165–8.

Dunkle-Blatter SE, St Jean MR, Whitehead C, et al. Outcomes among elderly bariatric patients at a high-volume center. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3(2):163–9.

Leivonen MK, Juuti A, Jaser N, et al. Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy in Patients over 59 Years: Early Recovery and 12-Month Follow-Up. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1180–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval and Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

For this type of study, formal consent is not required. Informed consent does not apply.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bartosiak, K., Różańska-Walędziak, A., Walędziak, M. et al. The Safety and Benefits of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy in Elderly Patients: a Case-Control Study. OBES SURG 29, 2233–2237 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03830-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03830-7