Abstract

Summary

This report describes epidemiology, burden, and treatment of osteoporosis in each of the 27 countries of the European Union plus Switzerland and the UK (EU 27+2).

Introduction

The aim of this report was to characterize the burden of osteoporosis in each of the countries of the European Union plus Switzerland and the UK in 2019 and beyond.

Methods

The data on fracture incidence and costs of fractures in the EU27+2 was taken from a concurrent publication in this journal (SCOPE 2021: a new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe) and country-specific information extracted. The information extracted covered four domains: burden of osteoporosis and fractures; policy framework; service provision; and service uptake.

Results

The clinical and economic burden of osteoporotic fractures in 2019 is given for each of the 27 countries of the EU plus Switzerland and the UK. Each domain was ranked and the country performance set against the scorecard for all nations studied. Data were also compared with the first SCOPE undertaken in 2010. Fifteen of the 16 score card metrics on healthcare provision were used in the two surveys. Scores had improved or markedly improved in 15 countries, remained constant in 8 countries and worsened in 3 countries. The average treatment gap increased from 55% in 2010 to 71% in 2019. Overall, 10.6 million women who were eligible for treatment were untreated in 2010. In 2019, this number had risen to 14.0 million.

Conclusions

In spite of the high cost of osteoporosis, a substantial treatment gap and projected increase of the economic burden driven by aging populations, the use of pharmacological prevention of osteoporosis has decreased in recent years, suggesting that a change in healthcare policy concerning the disease is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

*SCOPE review panel of the IOF

Country | Name | Affiliation | Contact |

|---|---|---|---|

Austria | Hans Peter Dimai | Division of Endocrinology and Diabetology, Department of Medicine, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria | hans.dimai@medunigraz.at |

Christian Muschitz | Medical Department II, St. Vincent Hospital, Vienna, Austria | christian.muschitz@meduniwien.ac.at | |

Belgium | Jean-Francois Kaux | Department of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, University Hospital and University of Liège, Belgium | jfkaux@chuliege.be |

Jean-Yves Reginster | Division of Public Health, Epidemiology and Health Economics, University of Liège, World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Public Health aspects of musculo-skeletal health and ageing, Liège, Belgium | jyr.ch@bluewin.ch | |

Biochemistry Department, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. | |||

Olivier Bruyère | Division of Public Health, Epidemiology and Health Economics, University of Liège, World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Public Health aspects of musculo-skeletal health and ageing, Liège, Belgium | olivier.bruyere@uliege.be | |

Etienne Cavalier | Department of Clinical Chemistry, CHU de Liege, University of Liege, Liège, Belgium. | Etienne.Cavalier@uliege.be | |

Marie-Paule Lecart | University of Liège, Bone and Cartilage Metabolism Research Unit, Department of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, Department of Geriatrics, CHU Centre Ville, Liège, Belgium | mplecart@chuliege.be | |

Bulgaria | Anna-Maria Borissova | University Hospital Sofiamed, Faculty of Medicine, Sofia University “Saint Kliment Ohridski”, Sofia-, Bulgaria; Bulgarian League for the Prevention of Osteoporosis | anmarbor@abv.bg |

Mihail Boyanov | University Hospital Alexandrovska, Sofia, Bulgaria; Bulgarian Society for Clinical Densitometry | mihailboyanov@yahoo.com | |

Zlatimir Kolarov | University Hospital Sv. Ivan Rilski, Department of Rheumatology, Faculty of Medicine, Medical University Sofia, Sofia, Bulgaria; Bulgarian Association for Osteoporosis and Osteoarthrosis | zkolarov@abv.bg | |

Croatia | Simeon Grazio | Department of Rheumatology, Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, University Clinical Centre Sisters of Mercy, Zagreb, Croatia | simeon.grazio@zg.t-com.hr |

Velimir Altabas | Department of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases, University Clinical Centre Sisters of Mercy, Zagreb, Croatia | velimir.altabas@gmail.com | |

Zlatko Giljević | Department of Endocrinology, University Clinical Centre Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia | zlatko.giljevic@kbc-zagreb.hr | |

Cyprus | George L Georgiades | Deputy President of the Cyprus Association against Osteoporosis | geoendo@cytanet.com.cy |

Czechia | Vladimir Palicka | Osteology Centre, University Hospital and School of Medicine, Charles University, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic | Palicka@lfhk.cuni.cz |

Richard Pikner | Department of Clinical Biochemistry and Bone Metabolism, Klatovy Hospital, Klatovy, Czech Republic | richard.pikner@klatovy.nemocnicepk.cz | |

Department of Clinical Biochemistry and Haematology, Faculty of Medicine Pilsen, Charles University Prague, Pilsen, Czech Republic | |||

Faculty of Health Care Studies, University of West Bohemia, Pilsen, Czech Republic | |||

Jan Rosa | Osteology Centre, Affidea Praha, Prague, Czech Republic | rosaj@affidea-praha.cz | |

Petr Kasalicky | Osteology Centre, Affidea Praha, Prague, Czech Republic | kasalickyp@affidea-praha.cz | |

Denmark | Pernille Hermann | Department of Endocrinology, Odense University Hospital, Denmark | Pernille.Hermann@rsyd.dk |

Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark | |||

Bo Abrahamsen | Department of Medicine, Holbæk Hospital, DK-4300, Holbæk, Denmark. | b.abrahamsen@physician.dk. | |

Estonia | Katre Maasalu | Tartu University Hospital, Clinic of Traumatology and Orthopaedics, Estonia | katre.maasalu@kliinikum.ee |

University of Tartu, Department of Traumatology and Orthopaedics, Estonia | |||

Eiki Strauss | Tartu University Hospital, Clinic of Traumatology and Orthopaedics, Estonia | eiki.strauss@kliinikum.ee | |

Finland | Ansa Holm | Suomen Luustoliitto ry, Köydenpunojankatu 8 G, 00180 Helsinki, Finland | ansa.holm@luustoliitto.fi |

France | Bernard Cortet | Department of Rheumatology and EA 4490, University-Hospital of Lille, Lille, France | Bernard.CORTET@CHRU-LILLE.FR |

Thierry Thomas | Department of Rheumatology, Hôpital Nord, CHU Saint-Etienne, and INSERM U1059, Lyon University, Saint-Etienne, France | thierry.thomas@chuse.fr | |

Laurent Grange | Department of Rheumatology, AFLAR, Grenoble Alpes University Hospital, Grenoble, France | LGrange@chu-grenoble.fr | |

Francoise Alliot Launois | AFLAR - Association Française de Lutte Anti-Rhumatismale, Paris, France. | francoisealliotlaunois@gmail.com | |

Germany | Gisela Klatt | Bundesselbsthilfeverband für Osteoporose e.V. (BfO) Federal Self-Help Association for Osteoporosis, Düsseldorf, Germany | gisela-klatt@t-online.de |

Stephan Scharla | Salinenstr. 8, 83435 Bad Reichenhall, Germany. | sscharla@gmx.de | |

Andreas Kurth | Department of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, Campus Kemperhof, Community Clinics Middle Rhine, Koblenz - Germany | kurth@dv-osteologie.de | |

Greece | Polyzois Makras | Department of Endocrinology and Diabetes, 251 Hellenic Air Force General Hospital, Athens, Greece, | pmakras@gmail.com |

Tatiana Drakopoulou | Butterfly Bone Health Society, Athens, Greece | tatiana@osteocare.gr | |

George Trovas | Laboratory of musculoskeletal diseases, University of Athens, Athens, Greece | trovas1@otenet.gr | |

George P Lyritis, | Hellenic Osteoporosis Foundation, Athens, Greece | glyritis@heliost.gr | |

Stavroula Rizou | Hellenic Osteoporosis Foundation, Athens, Greece | st.rizou@heliost.gr | |

Hungary | Istvan Takacs | Semmelweis University, Department of Internal Medicine and Oncology | takacs.istvan@med.semmelweis-univ.hu |

Judit Donáth | National Institute of Rheumatology and Physiotherapy, Budapest, Hungary | donjudit@gmail.com | |

László Szekeres | National Institute of Rheumatology and Physiotherapy, Budapest, Hungary | szekeres.laszlo@mail.orfi.hu | |

Ireland | Moira O'Brien | Irish Osteoporosis Society, Clonskeagh, Dublin, Ireland | info@irishosteoporosis.ie |

Michelle O’Brien | Irish Osteoporosis Society, Clonskeagh, Dublin, Ireland | info@irishosteoporosis.ie | |

Italy | Ferdinando Silveri | Department of Rheumatology, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, Italy | ferdinando.silveri@sanita.marche.it |

Italian Federation of Osteoporosis and Diseases of the Skeleton (FEDIOS), Falconara Marittima, Italy | |||

Maurizio Rossini | Rheumatology Unit, University of Verona, Policlinico Borgo Roma, Verona, Italy | maurizio.rossini@univr.it | |

Italian Society for Osteoporosis, Mineral Metabolism and Bone Diseases (SIOMMMS), Verona, Italy | |||

Maria Luisa Brandi | Fondazione Italiana sulla Ricerca per le Malattie dell'Osso (F.I.R.M.O.), Florence, Italy | info@fondazionefirmo.com | |

Latvia | Ingvars Rasa | Latvian Osteoporosis and Bone Metabolic Diseases Association (LOKMSA), Riga East Clinical University Hospital Rīga Stradiņš University; Riga, Latvia | dr.irasa@inbox.lv |

Lithuania | Alekna Vidmantas | Faculty of Medicine, Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania | vidmantas.alekna@osteo.lt |

Marija Tamulaitiene | Faculty of Medicine, Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania | marija.tamulaitiene@mf.vu.lt | |

Malta | Raymond Galea | Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Malta, Mater Dei Hospital, Malta | raymond.galea@um.edu.mt |

Malta Osteoporosis Society, c/o Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Sptar Mater Dei, Malta | |||

Neville Calleja | Health Information & Research, Ministry for Health, Malta | neville.calleja@gov.mt | |

Netherlands | Harry van den Broek | Osteoporose Vereniging, PO Box 418,2000 AK Haarlem, Netherlands | hvdbroek@osteoporosevereniging.nl |

Geraldine EMP Willemsen-De Mey | National Association ReumaZorg Nederland, Nijmegen, Netherlands | voorzitter@reumazorgnederland.nl | |

Hendrien Witte | Osteoporose Vereniging, PO Box 418,2000 AK Haarlem, Netherlands | hwitte@osteoporosevereniging.nl | |

Poland | Edward Czerwiński | Jagiellonian University, Faculty of Health Sciences, Institute of Physiotherapy, Rehabilitation Clinics, Krakow, Poland | czerwinski@kcm.pl |

Janusz E. Badurski | The Polish Foundation of Osteoporosis Research Team, Białystok, Poland. | badurski@pfo.com.pl | |

Portugal | José António P. Da Silva | Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, Portugal | jdasilva@ci.uc.pt |

António Tirado | Portuguese Society of Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Diseases (SPODOM), Lisbon, Portugal. | tirado.antonio2@icloud.com | |

Ana Paula Barbosa | Portuguese Society of Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Diseases (SPODOM), Lisbon, Portugal. | apgsb1@gmail.com | |

Ana Rodrigues | Portuguese Society of Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Diseases (SPODOM), Lisbon, Portugal. | anamfrodrigues@gmail.com | |

Ana Pires Gonçalves | Portuguese Society of Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Diseases (SPODOM), Lisbon, Portugal. | aa.pgoncalves@gmail.com | |

Romania | Andrea Ildiko Gasparik | Department of Public Health and Health Management, University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Tirgu Mures, Tirgu Mures, Romania. | ildikogasparik@gmail.com |

Ionela Pascanu | Department of Endocrinology, University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Science and Technology (UMFST) G.E. Palade of Tg. Mures, Romania | iopascanu@gmail.com | |

Daniel Grigorie | National Institute of Endocrinology, Carol Davila University of Medicine, Bucharest, Romania. | grigorie_d@yahoo.com | |

Slovakia | Juraj Payer | Comenius University Faculty of Medicine in Bratislava, 5. Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital Bratislava, Bratislava, Slovakia | payer@ruzinov.fnspba.sk |

Pavol Masarky | National Institute of Rheumatology, Piešťany, Slovakia | pavol.masaryk@nurch.sk | |

Peter Jackuliak | Comenius University Faculty of Medicine in Bratislava, 5. Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital Bratislava, Bratislava, Slovakia | peter.jackuliak@fmed.uniba.sk | |

Slovenia | Tomaz Kocjan | Department of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolic Diseases, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia | tomaz.kocjan@kclj.si |

Faculty of Medicine, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia | |||

Spain | Santiago Palacios | Palacios Institute of Women's Health, Madrid, Spain. | spalacios@institutopalacios.com |

Manuel Naves-Díaz | Bone and Mineral Research Unit, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias (ISPA), Retic REDinREN-ISCIII, Oviedo, Spain. | mnaves.huca@gmail.com | |

Adolfo Diez-Perez | Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital del Mar/IMIM and CIBERFES, Autonomous University of Barcelona, , Barcelona, Spain. | ADiez@parcdesalutmar.cat. | |

Sweden | Kristina E Åkesson | Department of Clinical Sciences, Clinical and Molecular Osteoporosis Research Unit Malmö, Lund University, Lund, Sweden. | kristina.akesson@med.lu.se |

Department of Orthopaedics, Skåne University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden. | |||

Bo Freyschuss | Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden | bo.freyschuss@ki.se | |

Switzerland | Serge Ferrari | Service and Laboratory of Bone Diseases, Geneva University Hospital and Faculty of Medicine, Geneva, Switzerland. | Serge.Ferrari@unige.ch |

Rene Rizzoli | University Hospitals and Faculty of Medicine of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland | Rene.Rizzoli@unige.ch | |

United Kingdom | M Kassim Javaid | Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. | kassim.javaid@ndorms.ox.ac.uk |

Craig Jones | Royal Osteoporosis Society, Bath, UK | Craig.Jones@theros.org.uk | |

Cyrus Cooper | MRC Lifecourse Epidemiology Unit, Southampton General Hospital, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. | cc@mrc.soton.ac.uk | |

IOF | Philippe Halbout | International Osteoporosis Foundation, Nyon, Switzerland | phalbout@iofbonehealth.org |

Table of Contents

Page | ||

|---|---|---|

Introduction | 5 | |

Epidemiology and economic burden of osteoporosis in | ||

1. | Austria | 6 |

2. | Belgium | 11 |

3. | Bulgaria | 15 |

4. | Croatia | 19 |

5. | Cyprus | 23 |

6. | Czech Republic | 27 |

7. | Denmark | 32 |

8. | Estonia | 37 |

9. | Finland | 42 |

10. | France | 46 |

11. | Germany | 50 |

12. | Greece | 54 |

13. | Hungary | 58 |

14. | Ireland | 62 |

15. | Italy | 66 |

16. | Latvia | 71 |

17. | Lithuania | 75 |

18. | Luxembourg | 79 |

19. | Malta | 83 |

20. | Netherlands | 87 |

21. | Poland | 91 |

22. | Portugal | 95 |

23. | Romania | 99 |

24. | Slovakia | 104 |

25. | Slovenia | 108 |

26. | Spain | 112 |

27. | Sweden | 116 |

28. | Switzerland | 120 |

29. | United Kingdom | 125 |

Introduction

Osteoporosis, literally “porous bone,” is a disease characterized by weak bone. It is a major public health problem, affecting hundreds of millions of people worldwide, predominantly postmenopausal women. The main clinical consequence of the disease is bone fractures. It is estimated that one in three women and one in five men over the age of fifty worldwide will sustain an osteoporotic fracture. Hip and spine fractures are the two most serious fracture types, associated with substantial pain and suffering, disability, and even death. As a result, osteoporosis imposes a significant burden on both the individual and society. Over the past three decades, a range of medications has become available for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis. The primary aim of pharmacological therapy is to reduce the risk of osteoporotic fractures.

A recent report “SCOPE 2021: a new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe” describes the current burden of osteoporosis in the EU in 2019 [1]. In 2019, 25.5 million women and 6.5 million men were estimated to have osteoporosis in the European Union plus Switzerland and the United Kingdom; and 4.3 million new fragility fractures were sustained, comprising 827,000 hip fractures, 663,000 vertebral fractures, 637,000 forearm fractures and 2,150,000 other fractures (i.e., fractures of the pelvis, rib, humerus, tibia, fibula, clavicle, scapula, sternum, and other femoral fractures). The economic burden of incident and prior fragility fractures in 2019 was estimated at € 57 billion. In the EU27+2, there were estimated to be 248,487 causally related deaths in 2019. The number of fracture-related deaths are comparable to or exceed some of the most common causes of death such as lung cancer, diabetes, chronic lower respiratory diseases. The population age 50 years or more is projected to increase by 11.4% in men and women between 2019 and 2034 and the annual number of osteoporotic fractures in the EU27+2 will increase by 25%. The majority of individuals who have sustained an osteoporosis-related fracture or who are at high risk of fracture are untreated and the proportion of high risk patients on treatment is declining.

The objective of this report is to review and describe the current burden of osteoporosis in each of the EU member states plus Switzerland and the UK. Epidemiological and health economic aspects of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures are summarised for 2019 with projections of the future prevalence of osteoporosis, the number of incident fractures, the direct and total cost of the disease including the value of QALYs lost. The report also provides information on the policy framework together with service provision and service uptake within each country. The report may serve as a basis for the formulation of healthcare policy concerning osteoporosis in general and the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis in particular. It may also provide guidance regarding the overall healthcare priority of the disease in each member state.

References

1. Kanis JA, Norton N, Harvey NC, Jacobson T, Johansson H Lorentzon M, McCloskey EV, Willers C, Borgström F (2021) SCOPE 2021: a new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe. Arch Osteoporos 16: 82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-020-00871-9

Epidemiology and economic burden of osteoporosis in Austria

HP Dimai ∙ C Muschitz ∙ C Willers ∙ N Norton ∙ NC Harvey ∙ T Jacobson ∙ H Johansson ∙ M Lorentzon ∙ EV McCloskey ∙ F Borgström ∙ JA Kanis

Introduction

The scorecard summarises key indicators of the burden of osteoporosis and its management in the 27 member states of the European Union, as well as the UK and Switzerland (termed EU27+2) [1]. This country-specific report summarises the principal results for Austria.

Methods

The information obtained covers four domains: burden of osteoporosis and fractures; policy framework; service provision; and service uptake. Data were collected from numerous sources including previous research and IOF reports, and available registers which were used for additional analysis of resource utilization, costing and HRQoL data. Furthermore, country-specific information on osteoporosis management was obtained from each IOF member state via a questionnaire.

Burden of disease

The direct cost of incident fractures in Austria in 2019 was €833.5 million. Added to this was the ongoing cost in 2019 from fractures that occurred before 2019, which amounted to €468.1 million (long-term disability). The cost of pharmacological intervention (assessment and treatment) was €41.7 million. Thus, the total direct cost (excluding the value of QALYs lost) amounted to €1.3 billion in 2019. Key metrics are presented in Table 1.

In 2019, the average direct cost of osteoporotic fractures in Austria was €151.8 per individual in the population, while in 2010 the average was €104.8 (after adjusting for inflation) representing a relative increase of 45% (€151.8 versus €104.8). The 2019 numbers put Austria in the 6th place in terms of highest cost of osteoporotic fractures per capita in the EU27+2.

The cost of osteoporotic fractures in Austria accounted for approximately 3.4% of healthcare spending (i.e. €1.3 billion out of €38.7 billion in 2019), close to the EU27+2 average of 3.5% placing Austria at 13th in the ranked order across the EU27+2 countries. These numbers indicate a substantial impact of fragility fractures on the healthcare budget.

Using World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis based on the measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) [2], there were approximately 552,000 individuals with osteoporosis in Austria in 2019, of whom almost 80% were women. The prevalence of osteoporosis in the total Austrian population amounted to 5.5%, on par with the EU27+2 average (5.6%).

Table 1 Key measures of burden of disease for Austria

Category | Measure | Estimate | Rank (EU27+2) |

|---|---|---|---|

Burden of disease | Direct cost of incident fracture (€m) | 833.5 | |

Long-term disability cost (€m) | 468.1 | ||

Intervention cost (€m) | 41.7 | ||

Total cost (€m) | 1 343 | ||

QALYs lost (€m) | 4 111 | ||

Cost per capita (€) | 151.8 | 6 | |

Proportion of healthcare spending | 3.4% | 13 | |

Prevalence of osteoporosis | 5.5% | 12 |

There were estimated to be 110,000 new fragility fractures in Austria in 2019, equivalent to 300 fractures/day (or 12 per hour). This was a slight increase compared to 2010, equivalent to an increment of 1.1 fractures/1000 individuals, totalling 29.6 fractures/ 1000 individuals in 2019.

Some osteoporotic fractures are associated with premature mortality [3]. In Austria, the annual number of deaths associated with a fracture event was estimated to be 165 per 100,000 individuals of the population aged 50 years or more, compared to the EU27+2 average of 116/100,000. The number of fracture-related deaths is comparable to or exceeds that for some of the most common causes of death such as lung cancer, diabetes, chronic lower respiratory diseases.

The remaining lifetime probability of hip fracture (%) at the ages of 50 years in men and women was 8.3% and 19.7% respectively, placing Austria in the upper tertile of risk for both men and women.

The population of men and women age 50 years or more is projected to increase by 11.8% in men and women between 2019 and 2034, close to the EU27+2 average of 11.4%. The increases in men and women aged 75 years or more are even more marked and amount to 38.0% and 22.0%, respectively. The annual number of osteoporotic fractures in Austria is expected to increase by 30,000 to 140,000 in 2034.

Policy framework (Table 2)

Documentation of the burden of disease is an essential prerequisite to determine the resources that should be allocated to the diagnosis and treatment of the disorder. High quality national data on hip fracture rates have been identified in 18 of 29 countries, of which Austria is one. Data are collected on a national basis and include more than only hip fracture data.

Given that osteoporosis and fragility fractures are common and that effective treatments are widely available, the vast majority of patients with osteoporosis are preferably managed at the primary health care level by general practitioners (GPs), with specialist referral reserved for difficult complex cases. Primary care was the principal provider of the medical care for osteoporosis in Austria, as for 13 of the 28 countries where data were available.

Osteoporosis and metabolic bone disease is not a recognised specialty in most countries including Austria. Specialty care of osteoporosis in Austria is via other specialties including endocrinology, gynaecology, orthopaedic surgery and rheumatology. Osteoporosis is however recognized as a component of specialty training. Although it is possible that these specialties educate their trainees adequately, the wide variation may reflect inconsistencies in patient care, training of primary care physicians and a suboptimal voice to “defend” the interests of those who work within the field of osteoporosis.

Table 2 Policy framework for osteoporosis in Austria

Category | Measure | Estimate |

|---|---|---|

Policy framework | National fracture data availability | Yes |

OP recognized as a specialty | No | |

OP primarily managed in primary care | Yes | |

Other specialties involved | Endocrinology, Rheumatology, Gynaecology, Orthopaedics | |

Advocacy areas covered by patient organisation | Policy, capacity, peer support, research and development |

The role of national patient organisations is to improve the care of patients and increase awareness and prevention of osteoporosis and related fractures among the general public. Advocacy by patient organisations can fall into four categories: policy, capacity building and education, peer support, research and development. For Austria, all four of the advocacy areas were covered by a patient organisation, which was the case for only 10 out of the 26 countries with at least one patient organisation.

Service provision (Table 3)

A wide variety of approved drug treatments is available for the management of osteoporosis [4]. Potential limitations of their use in member states relate to reimbursement policies which may impair the delivery of health care. Austria is one of the 12 (out of 27) countries that offer full reimbursement.

The assessment of bone mineral density forms a key component for the general management of osteoporosis, being used for diagnosis, risk prediction, selection of patients for treatment and monitoring of patients on treatment. In Austria, the number of DXA units expressed per million of the general population amounted to 29.7 which puts the country in the 3rd place among the EU27+2. Furthermore, the availability of TBS was highest in Austria.

The average waiting time for DXA ranged from 0 to 180 days across countries, and there was no clear relation between waiting times and the availability of DXA. In Austria, the estimated average waiting time for DXA amounted to 14 days. Nine countries reported shorter average waiting times.

Table 3 Service provision for osteoporosis in Austria

Category | Measure | Estimate | Rank (EU27+2) |

|---|---|---|---|

Service provision | Reimbursement of OP medications | 100% | |

DXA units/million inhabitants | 29.7 | 3 | |

DXA cost (€) | 50 | 12 | |

FRAX risk assessment model available | Yes | ||

Fracture liaison service density | 1-10% |

Reimbursement for DXA scans varied between member states both in terms of the criteria required and level of reimbursement awarded. In Austria, the reimbursement was conditional and varied depending on public versus private delivery of the service.

The effective targeting of treatment to those at highest risk of fracture requires an assessment of fracture risk. Risk assessment models for fractures, most usually based on FRAX, were available in 24 out of 29 countries, of which Austria was one. An additional risk assessment model, DVO, was also used in Austria. For Austria, guidance on the use of risk assessment within national guidelines was available, as in only 14 of the other countries.

Guidelines for the management of osteoporosis were available in Austria (as in 27 out of 29 countries). The guidelines in Austria included postmenopausal women specifically, as well as for osteoporosis in men and for secondary osteoporosis including glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.

Fracture liaison services (FLS), also known as osteoporosis coordinator programmes and care manager programmes, provide a system for the routine assessment and management of postmenopausal women and older men who have sustained a low trauma fracture. Fracture liaison services were reported for 1–10% of the hospitals in Austria.

The use of indicators to systematically measure the quality of care provided to people with osteoporosis or associated fractures has expanded as a discipline within the past decade [5]. No use of national quality indicators was reported for Austria.

Service uptake (Table 4)

The web-based usage of FRAX showed considerable heterogeneity in uptake between the countries. The average uptake for the EU27+2 was 1,555 sessions/million/year of the general population with an enormous range of 49 to 41,874 sessions/million. The usage for Austria amounted to 2,439 sessions/million in 2019, with a 59% increase since 2011.

Many studies have demonstrated that a significant proportion of men and women at high fracture risk do not receive therapy for osteoporosis (the treatment gap) [6]. In the EU27+2 the average treatment gap was 71% but ranged from 32 to 87%. For Austria, the treatment gap amongst women amounted to 52% or 168,000 out of 325,000 characterised at risk. The Austrian treatment gap did not change significantly compared to 2010, whilst the average treatment gap among EU27+2 increased from 55% in 2010 to 71% in 2019. In recent nationwide study, the treatment gap 4, 12 and 18 months after the first hip fracture was 82 %, 84 % and 85 % in women, and 92 %, 88 % and 90 % in men, respectively [7].

Table 4 Service uptake for osteoporosis in Austria

Category | Measure | Estimate | Rank (EU27+2) |

|---|---|---|---|

Service uptake | Number of FRAX sessions/million people/year | 2439 | 10 |

Treatment gap for women eligible for treatment (%) | 52 | 4 | |

Proportion surgically managed hip fractures | >90% |

About 5% of people with a hip fracture die within 1 month of their fracture [8]. A determinant of peri-operative morbidity and mortality is the time a patient takes to get to surgery [9]. For Austria, the average waiting time for hip fracture surgery after hospital admission was reported to be less than 24 h, implying a reduction in waiting time compared to 2010 (waiting time of 1–2 days). The proportion of surgically managed hip fractures was reported to be over 90%.

Scores and scorecard

Scores were developed for Burden of disease and the healthcare provision (Policy framework, Service provision and Service uptake) in the EU27+2 countries. Austria scores resulted in a 4th place regarding Burden of disease after only Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland. The combined healthcare provision scorecard resulted in a 7th place for Austria. Thus, Austria presents as one of the eight high-burden high-provision countries among the EU27+2.

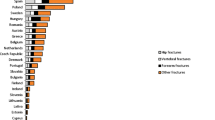

Fig. 1 Scores by country for metrics related to policy framework, service provision and service uptake. The mean score for each of the 3 domains is given. An asterisk denotes that there was one or more missing metric which decreases the overall score

The first SCOPE was undertaken in 2010, almost 10 years previously. Fifteen of the 16 score card metrics on healthcare provision were used in the two surveys. Scores had improved or markedly improved in 15 countries, remained constant in 8 countries and worsened in 3 countries. For Austria the scores were somewhat improved.

Fig. 2 The scorecard for all the EU27+2 countries illustrating the scores across the four domains. The elements of each domain in each country were scored and coded using a traffic light system (red, orange, green). Black dots signify missing information

The second edition of the Scorecard for Osteoporosis in Europe (SCOPE 2021) allows health and policy professionals to assess key indicators on the healthcare provision for osteoporosis within countries and between counties within the EU 27+2. The scorecard is not intended as a prescriptive template. Thus, it does not set performance targets but may serve as a guide to the performance targets at which to aim in order to deliver the outcomes required.

Acknowledgements

SCOPE was supported by an unrestricted grant from Amgen to the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF). Amgen was neither involved in the design nor writing of the report. We are grateful to Anastasia Soulié Mlotek and Dominique Pierroz of the IOF for their help in the administration of SCOPE. The report has been reviewed by the members of the SCOPE Consultation Panel and the relevant IOF National societies, and we are grateful for their local insights on the management of osteoporosis in each country. The source document has been reviewed and endorsed by the Committee of Scientific Advisors of the IOF and benefitted from their feedback.

References

1. Kanis JA, Norton N, Harvey NC, Jacobson T, Johansson H, Lorentzon M, McCloskey EV, Willers C, Borgström F (2021) SCOPE 2021: a new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe. Arch Osteoporos 16:82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-020-00871-9

2. World Health Organisation (1994) Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser, 1994/01/01 edn, pp 1-129

3. Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Sernbo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Petterson C, De Laet C, Jonsson B (2004) Mortality after osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 15:38-42

4. Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergard M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J, McCloskey EV, Jonsson B, Kanis JA (2013) Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 8:136

5. Allen P, Pilar M, Walsh-Bailey C, Hooley C, Mazzucca S, Lewis CC, Mettert KD, Dorsey CN, Purtle J, Kepper MM, Baumann AA, Brownson RC (2020) Quantitative measures of health policy implementation determinants and outcomes: a systematic review. Implement Sci 15:47

6. Borgstrom F, Karlsson L, Ortsater G, Norton N, Halbout P, Cooper C, Lorentzon M, McCloskey EV, Harvey NC, Javaid MK, Kanis JA (2020) Fragility fractures in Europe: burden, management and opportunities. Arch Osteoporos 15:59

7. Malle O, Borgstrom F, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Svedbom A, Dimai SV, Dimai HP (2021) Mind the gap: Incidence of osteoporosis treatment after an osteoporotic fracture - results of the Austrian branch of the International Costs and Utilities Related to Osteoporotic Fractures Study (ICUROS). Bone 142:115071. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2019.115071.

8. Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oglesby AK (2003) The components of excess mortality after hip fracture. Bone 32:468-473

9. National Clinical Guideline Centre (2011) The Management of Hip Fracture in Adults. In Centre NCG (ed)London

Epidemiology and economic burden of osteoporosis in Belgium

JF Kaux ∙ J-Y Reginster ∙ O Bruyère ∙ E Cavalier ∙ M-P Lecart ∙ C Willers ∙ N Norton ∙ NC Harvey ∙ T Jacobson ∙ H Johansson ∙ M Lorentzon ∙ EV McCloskey ∙ F Borgström ∙ JA Kanis

Introduction

The scorecard summarises key indicators of the burden of osteoporosis and its management in the 27 member states of the European Union, as well as the UK and Switzerland (termed EU27+2) [1]. This country-specific report summarises the principal results for Belgium.

Methods

The information obtained covers four domains: burden of osteoporosis and fractures; policy framework; service provision; and service uptake. Data were collected from numerous sources including previous research and IOF reports, and available registers which were used for additional analysis of resource utilization, costing and HRQoL data. Furthermore, country-specific information on osteoporosis management was obtained from each IOF member state via a questionnaire.

Burden of disease

The direct cost of incident fractures in Belgium in 2019 was €766.4 million. Added to this was the ongoing cost in 2019 from fractures that occurred before 2019, which amounted to €321.9 million (long-term disability). The cost of pharmacological intervention (assessment and treatment) was €34.0 million. Thus, the total direct cost (excluding the value of QALYs lost) amounted to €1.1 billion in 2019. Key metrics are presented in Table 1.

In 2019, the average direct cost of osteoporotic fractures in Belgium was €98.3 per individual in the population, while in 2010 the average was €62.9 (after adjusting for inflation), representing a relative increase of 56% (€98.3 versus €62.9). The 2019 numbers put Belgium in 9th place in terms of highest cost of osteoporotic fractures per capita in the EU27+2.

The cost of osteoporotic fractures in Belgium accounted for approximately 2.4% of healthcare spending (i.e. €1.1 billion out of €45.7 billion in 2019), lower than the EU27+2 average of 3.5% and placed Belgium at 23rd in the ranked order across the EU27+2 countries.

Using World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis based on the measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) [2], there were approximately 681,000 individuals with osteoporosis in Belgium in 2019, of whom almost 80% were women. The prevalence of osteoporosis in the total Belgian population amounted to 5.6%, on par with the EU27+2 average (5.6%).

Table 1 Key measures of burden of disease for Belgium

Category | Measure | Estimate | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

Burden of disease | Direct cost of incident fracture (€m) | 766.36 | |

Long-term disability cost (€m) | 321.85 | ||

Intervention cost (€m) | 33.97 | ||

Total cost (€m) | 1122.18 | ||

QALYs lost (€m) | 3 079 | ||

Cost per capita (€) | 98.25 | 9 | |

Proportion of healthcare spending | 2.4% | 23 | |

Prevalence of osteoporosis | 5.6% | 8 |

There were estimated to be 100,000 new fragility fractures in Belgium in 2019, equivalent to 274 fractures/day (or 11 per hour). This was a slight increase compared to 2010, equivalent to an increment of 1.8 fractures/1000 individuals, totalling 22 fractures/ 1000 individuals in 2019.

Some osteoporotic fractures are associated with premature mortality [3]. In Belgium, the annual number of deaths associated with a fracture event was estimated to be 119 per 100,000 individuals of the population aged 50 years or more, compared to the EU27+2 average of 116/100,000. The number of fracture-related deaths is comparable to or exceeds that for some of the most common causes of death such as lung cancer, diabetes, chronic lower respiratory diseases.

The remaining lifetime probability of hip fracture (%) at the ages of 50 years in men and women was 7.8% and 18.2%, respectively, placing Belgium in the upper tertile of risk for both men and women.

The population of men and women age 50 years or more is projected to increase by 12.6% between 2019 and 2034, close to the EU27+2 average of 11.4%. The increases in men and women aged 75 years or more are even more marked and amount to 55.5% and 32.8%, respectively. The annual number of osteoporotic fractures in Belgium is expected to increase by 23,000 to 123,000 in 2034.

Policy framework (Table 2)

Documentation of the burden of disease is an essential prerequisite to determine the resources that should be allocated to the diagnosis and treatment of the disorder. High quality national data on hip fracture rates have been identified in 18 of 29 countries, of which Belgium is one. Data are collected on a national basis and include more than only hip fracture data.

Given that osteoporosis and fragility fractures are common and that effective treatments are widely available, the vast majority of patients with osteoporosis are preferably managed at the primary health care level by general practitioners (GPs), with specialist referral reserved for difficult complex cases. Primary care was the principal provider of the medical care for osteoporosis in Belgium, as for 13 of the 28 countries where data were available.

Osteoporosis and metabolic bone disease is not a recognised specialty in most countries including Belgium. Specialty care of osteoporosis in Belgium is via other specialties including rehabilitation medicine. Osteoporosis is however recognized as a component of specialty training. Although it is possible that trainees are educated adequately, the wide variation may reflect inconsistencies in patient care, training of primary care physicians and a suboptimal voice to “defend” the interests of those who work within the field of osteoporosis.

Table 2 Policy framework for osteoporosis in Belgium

Category | Measure | Estimate |

|---|---|---|

Policy framework | National fracture data availability | No |

OP recognized as a specialty | No | |

OP primarily managed in primary care | Yes | |

Other specialties involved | Rehabilitation medicine | |

Advocacy areas covered by patient organisation | None |

The role of national patient organisations is to improve the care of patients and increase awareness and prevention of osteoporosis and related fractures among the general public. Advocacy by patient organisations can fall into four categories: policy, capacity building and education, peer support, research and development. For Belgium, none of the advocacy areas were covered by a patient organisation. For 10 out of the 26 countries with at least one patient organisation, all advocacy areas were covered.

Service provision (Table 3)

A wide variety of approved drug treatments is available for the management of osteoporosis [4]. Potential limitations of their use in member states relate to reimbursement policies which may impair the delivery of health care. 12 (out of 27) countries offer full reimbursement, Belgium is not one of them.

The assessment of bone mineral density forms a key component for the general management of osteoporosis, being used for diagnosis, risk prediction, selection of patients for treatment and monitoring of patients on treatment. In Belgium, the number of DXA units expressed per million of the general population amounted to 28.9 which puts the country in the 4th place among the EU27+2.

The average waiting time for DXA ranged from 0 to 180 days across countries, and there was no clear relation between waiting times and the availability of DXA. In Belgium, the estimated average waiting time for DXA amounted to 7 days. Only four countries reported shorter average waiting times.

Table 3 Service provision for osteoporosis in Belgium

Category | Measure | Estimate | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

Service provision | Reimbursement of OP medications | 61-98% | |

DXA units/million inhabitants | 28,9 | 4 | |

DXA cost (€) | 93 | 5 | |

FRAX risk assessment model available | Yes | ||

Fracture liaison service density | N/A |

Reimbursement for DXA scans varied between member states both in terms of the criteria required and level of reimbursement awarded. In Belgium, the reimbursement was conditional.

The effective targeting of treatment to those at highest risk of fracture requires an assessment of fracture risk. Risk assessment models for fractures, most usually based on FRAX, were available in 24 out of 29 countries, of which Belgium was one. For Belgium, guidance on the use of risk assessment within national guidelines was available, as in only 14 of the other countries.

Guidelines for the management of osteoporosis were available in Belgium (as in 27 out of 29 countries). The guidelines in Belgium included postmenopausal women specifically, as well as for osteoporosis in men and for secondary osteoporosis including glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.

Fracture liaison services (FLS), also known as osteoporosis coordinator programmes and care manager programmes, provide a system for the routine assessment and management of postmenopausal women and older men who have sustained a low trauma fracture. No information on fracture liaison services was reported for Belgium.

The use of indicators to systematically measure the quality of care provided to people with osteoporosis or associated fractures has expanded as a discipline within the past decade [5]. No use of national quality indicators was reported for Belgium.

Service uptake (Table 4)

The web-based usage of FRAX showed considerable heterogeneity in uptake between the countries. The average uptake for the EU27+2 was 1,555 sessions/million/year of the general population with an enormous range of 49 to 41,874 sessions/million. The usage for Belgium amounted to 2,144 sessions/million in 2019, with a 57 percent decrease since 2011.

Many studies have demonstrated that a significant proportion of men and women at high fracture risk do not receive therapy for osteoporosis (the treatment gap) [6]. In the EU27+2 the average treatment gap was 71% but ranged from 32 to 87%. For Belgium, the treatment gap amongst women amounted to 66% or 291,000 out of 441,000 characterised at risk. The Belgian treatment gap grew significantly compared to 2010, as did the treatment gap among EU27+2 which increased from 55% in 2010 to 71% in 2019.

Table 4 Service uptake for osteoporosis in Belgium

Category | Measure | Estimate | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

Service uptake | Number of FRAX sessions/million people/year | 2144 | 11 |

Treatment gap for women eligible for treatment (%) | 66 | 10 | |

Proportion surgically managed hip fractures | >90% |

About 5% of people with a hip fracture die within 1 month of their fracture [7]. A determinant of peri-operative morbidity and mortality is the time a patient takes to get to surgery [8]. For Belgium, the average waiting time for hip fracture surgery after hospital admission was reported to be 1–2 days, implying an increase in waiting time compared to 2010 (waiting time of <24 h). The proportion of surgically managed hip fractures was reported to be over 90%.

Scores and scorecard

Scores were developed for Burden of disease and the healthcare provision (Policy framework, Service provision and Service uptake) in the EU27+2 countries. Belgium scores resulted in an 8th place regarding Burden of disease. The combined healthcare provision scorecard resulted in a 21st place for Belgium. Thus, Belgium presents as one of the eight high-burden low-provision countries among the EU27+2.

Fig. 1 Scores by country for metrics related to policy framework, service provision and service uptake. The mean score for each of the 3 domains is given. An asterisk denotes that there was one or more missing metric which decreases the overall score

The first SCOPE was undertaken in 2010, almost 10 years previously. Fifteen of the 16 score card metrics on healthcare provision were used in the two surveys. Scores had improved or markedly improved in 15 countries, remained constant in 8 countries and worsened in 3 countries. For Belgium, the scores were worse in 2019 compared to 2010.

Fig. 2 The scorecard for all the EU27+2 countries illustrating the scores across the four domains. The elements of each domain in each country were scored and coded using a traffic light system (red, orange, green). Black dots signify missing information

The second edition of the Scorecard for Osteoporosis in Europe (SCOPE 2021) allows health and policy professionals to assess key indicators on the healthcare provision for osteoporosis within countries and between countries within the EU 27+2. The scorecard is not intended as a prescriptive template. Thus, it does not set performance targets but may serve as a guide to the performance targets at which to aim in order to deliver the outcomes required.

Acknowledgements

SCOPE was supported by an unrestricted grant from Amgen to the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF). Amgen was neither involved in the design nor writing of the report. We are grateful to Anastasia Soulié Mlotek and Dominique Pierroz of the IOF for their help in the administration of SCOPE. We acknowledge the assistance of the Royal Belgian Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine and the Belgian Bone Club. We thank Stefan Goemaere, Ghent University Hospital, Belgium for his helpful input.The report has been reviewed by the members of the SCOPE Consultation Panel and the relevant IOF National societies, and we are grateful for their local insights on the management of osteoporosis in each country. The source document has been reviewed and endorsed by the Committee of Scientific Advisors of the IOF and benefitted from their feedback.

References

1. Kanis JA, Norton N, Harvey NC, Jacobson T, Johansson H, Lorentzon M, McCloskey EV, Willers C, Borgström F (2021) SCOPE 2021: a new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe. Arch Osteoporos 16:82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-020-00871-9

2. World Health Organisation (1994) Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser, 1994/01/01 edn, pp 1-129

3. Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Sernbo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Petterson C, De Laet C, Jonsson B (2004) Mortality after osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 15:38-42

4. Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergard M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J, McCloskey EV, Jonsson B, Kanis JA (2013) Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 8:136

5. Allen P, Pilar M, Walsh-Bailey C, Hooley C, Mazzucca S, Lewis CC, Mettert KD, Dorsey CN, Purtle J, Kepper MM, Baumann AA, Brownson RC (2020) Quantitative measures of health policy implementation determinants and outcomes: a systematic review. Implement Sci 15:47

6. Borgstrom F, Karlsson L, Ortsater G, Norton N, Halbout P, Cooper C, Lorentzon M, McCloskey EV, Harvey NC, Javaid MK, Kanis JA (2020) Fragility fractures in Europe: burden, management and opportunities. Arch Osteoporos 15:59

7. Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oglesby AK (2003) The components of excess mortality after hip fracture. Bone 32:468-473

8. National Clinical Guideline Centre (2011) The Management of Hip Fracture in Adults. In Centre NCG (ed)London

Epidemiology and economic burden of osteoporosis in Bulgaria

A-M Borissova ∙ M Boyanov ∙ Z Kolarov ∙ C Willers ∙ N Norton ∙ NC Harvey ∙ T Jacobson ∙ H Johansson ∙ M Lorentzon ∙ EV McCloskey ∙ F Borgström ∙ JA Kanis

Introduction

The scorecard summarises key indicators of the burden of osteoporosis and its management in the 27 member states of the European Union, as well as the UK and Switzerland (termed EU27+2) [1]. This country-specific report summarises the principal results for Bulgaria.

Methods

The information obtained covers four domains: burden of osteoporosis and fractures; policy framework; service provision; and service uptake. Data were collected from numerous sources including previous research and IOF reports, and available registers which were used for additional analysis of resource utilization, costing and HRQoL data. Furthermore, country-specific information on osteoporosis management was obtained from each IOF member state via a questionnaire.

Burden of disease

The direct cost of incident fractures in Bulgaria in 2019 was €135.1 million. Added to this was the ongoing cost in 2019 from fractures that occurred before 2019, which amounted to €41.3 million (long-term disability). The cost of pharmacological intervention (assessment and treatment) was €9.2 million. Thus, the total direct cost (excluding the value of QALYs lost) amounted to €186 million in 2019. Key metrics are presented in Table 1.

In 2019, the average direct cost of osteoporotic fractures in Bulgaria was €26.4 per individual in the population, while in 2010 the average was €6.6 (after adjusting for inflation), representing a relative increase of 299% (€26.4 versus €6.6) The 2019 numbers put Bulgaria in the 25th place in terms of cost of osteoporotic fractures per capita in the EU27+2.

The cost of osteoporotic fractures in Bulgaria accounted for approximately 4.2% of healthcare spending (i.e. €186 million out of €4.2 billion in 2019), somewhat higher than the EU27+2 average of 3.5% and placed Bulgaria at the 9th place in the rank order of the EU27+2 countries. These numbers indicate a substantial impact of fragility fractures on the healthcare budget.

Using World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis based on the measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) [2], there were approximately 420,000 individuals with osteoporosis in Bulgaria in 2019, of whom approximately 80% were women. The prevalence of osteoporosis in the total Bulgarian population amounted to 5.6%, on par with the EU27+2 average (5.6%).

Table 1 Key measures of burden of disease for Bulgaria

Category | Measure | Estimate | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

Burden of disease | Direct cost of incident fracture (€m) | 135.09 | |

Long-term disability cost (€m) | 41.30 | ||

Intervention cost (€m) | 9.19 | ||

Total cost (€m) | 185.58 | ||

QALYs lost (€m) | 327 | ||

Cost per capita (€) | 26.42 | 25 | |

Proportion of healthcare spending | 4.2% | 9 | |

Prevalence of osteoporosis | 5.6% | 9 |

There were estimated to be 56,000 new fragility fractures in Bulgaria in 2019, equivalent to 150 fractures/day (or 6.4 per hour). This was a significant increase compared to 2010, equivalent to an increment of 6.0 fractures/1000 individuals, totalling 19.3 fractures/ 1000 individuals in 2019.

Some osteoporotic fractures are associated with premature mortality [3]. In Bulgaria, the annual number of deaths associated with a fracture event was estimated to be 184 per 100,000 individuals of the population aged 50 years or more, compared to the EU27+2 average of 116/100,000. The number of fracture-related deaths is comparable to or exceeds that for some of the most common causes of death such as lung cancer, diabetes, chronic lower respiratory diseases.

The remaining lifetime probability of hip fracture (%) at the ages of 50 years in men and women was 4.4% and 11.2%, respectively [4], placing Bulgaria in the lower tertile of risk for both men and women.

The Bulgarian population of men and women age 50 years or more is projected to decrease by 0.1% between 2019 and 2034, compared to the EU27+2 average of an increase with 11.4%. The number of men and women aged 75 years in Bulgaria are however projected to increase with 20.1% and 19.7%, respectively. The annual number of osteoporotic fractures in Bulgaria is expected to increase by 5,000 to 61,000 in 2034.

Policy framework (Table 2)

Documentation of the burden of disease is an essential prerequisite to determine the resources that should be allocated to the diagnosis and treatment of the disorder. High quality national data on hip fracture rates have been identified in 18 of 29 countries, of which Bulgaria is one. Data are collected on a national basis and include more than only hip fracture data.

Given that osteoporosis and fragility fractures are common and that effective treatments are widely available, the vast majority of patients with osteoporosis are preferably managed at the primary health care level by general practitioners (GPs), with specialist referral reserved for difficult complex cases. Primary care was the principal provider of the medical care for osteoporosis in 13 of the 28 countries where data were available. In Bulgaria, the lead specialty for osteoporosis was reported to be rheumatology.

Osteoporosis and metabolic bone disease is not a recognised specialty in most countries including Bulgaria. Specialty care of osteoporosis in Bulgaria is managed via specialties including rheumatology, endocrinology, internal medicine and orthopaedics. Osteoporosis is however recognized as a component of specialty training. Although it is possible that these specialties educate their trainees adequately, the wide variation may reflect inconsistencies in patient care, training of primary care physicians and a suboptimal voice to “defend” the interests of those who work within the field of osteoporosis.

Table 2 Policy framework for osteoporosis in Bulgaria

Category | Measure | Estimate |

|---|---|---|

Policy framework | National fracture data availability | Yes |

OP recognized as a specialty | No | |

OP primarily managed in primary care | No | |

Other specialties involved | Rheumatology, Endocrinology. Internal medicine, Orthopaedics | |

Advocacy areas covered by patient organisation | None |

The role of national patient organisations is to improve the care of patients and increase awareness and prevention of osteoporosis and related fractures among the general public. Advocacy by patient organisations can fall into four categories: policy, capacity building and education, peer support, research and development. For Bulgaria, none of the advocacy areas were covered by a patient organisation, whilst 10 out of the 26 countries with at least one patient organisation had all four areas covered.

Service provision (Table 3)

A wide variety of approved drug treatments is available for the management of osteoporosis [5]. Potential limitations of their use in member states relate to reimbursement policies which may impair the delivery of health care. Twelve out of 27 countries offered full reimbursement, and Bulgaria belonged to the remaining 15 countries offering partial reimbursement.

The assessment of bone mineral density forms a key component for the general management of osteoporosis, being used for diagnosis, risk prediction, selection of patients for treatment and monitoring of patients on treatment. In Bulgaria, the number of DXA units expressed per million of the general population amounted to 3.6 which puts the country in the 28th place among the EU27+2.

The average waiting time for DXA ranged from 0 to 180 days across countries, and there was no clear relation between waiting times and the availability of DXA. In Bulgaria, the estimated average waiting time for DXA amounted to five days. Only three countries reported shorter average waiting times. Reimbursement for DXA scans varied between member states both in terms of the criteria required and level of reimbursement awarded.

Table 3 Service provision for osteoporosis in Bulgaria

Category | Measure | Estimate | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

Service provision | Reimbursement of OP medications | 50% | |

DXA units/million inhabitants | 3.6 | 28 | |

DXA cost (€) | 50 | 14 | |

FRAX risk assessment model available | From 2020 | ||

Fracture liaison service density | No FLS |

The effective targeting of treatment to those at highest risk of fracture requires an assessment of fracture risk. Risk assessment models for fractures, most usually based on FRAX, were available in 24 out of 29 countries. Since this survey, Bulgaria has become the 25th country with a risk assessment model. For Bulgaria, guidance on the use of risk assessment within national guidelines was not yet available, as it was in 14 of the other countries.

Guidelines for the management of osteoporosis were available in Bulgaria (as in 27 out of 29 countries). The guidelines in Bulgaria included postmenopausal women specifically, as well as osteoporosis in men and secondary osteoporosis including glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.

Fracture liaison services (FLS), also known as osteoporosis coordinator programmes and care manager programmes, provide a system for the routine assessment and management of postmenopausal women and older men who have sustained a low trauma fracture. No fracture liaison services were reported from Bulgaria (together with seven other countries).

The use of indicators to systematically measure the quality of care provided to people with osteoporosis or associated fractures has expanded as a discipline within the past decade [6]. No use of national quality indicators was reported for Bulgaria.

Service uptake (Table 4)

The web-based usage of FRAX showed considerable heterogeneity in uptake between the countries. The average uptake for the EU27+2 was 1,555 sessions/million/year of the general population with an enormous range of 49 to 41,874 sessions/million. The usage for Bulgaria amounted to 49 sessions/million in 2019 (placing the country last amongst EU 27+2), with a 56 percent decrease since 2011.

Many studies have demonstrated that a significant proportion of men and women at high fracture risk do not receive therapy for osteoporosis (the treatment gap) [7]. In the EU27+2 the average treatment gap was 71% but ranged from 32 to 87%. For Bulgaria, the treatment gap amongst women amounted to 87% or 239,000 out of 273,000 characterised at risk. The Bulgarian treatment gap decreased by more than 5% compared to 2010, whilst the average treatment gap among EU27+2 increased from 55% in 2010 to 71% in 2019

Table 4 Service uptake for osteoporosis in Bulgaria

Category | Measure | Estimate | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

Service uptake | Number of FRAX sessions/million people/year | 49 | 29 |

Treatment gap for women eligible for treatment (%) | 87 | 27 | |

Proportion surgically managed hip fractures | 75–90% |

About 5% of people with a hip fracture die within 1 month of their fracture [8]. A determinant of peri-operative morbidity and mortality is the time a patient takes to get to surgery [9]. For Bulgaria, the average waiting time for hip fracture surgery after hospital admission was reported to be less than 24 h, implying a reduction in waiting time compared to 2010 (waiting time of 1–2 days). The proportion of surgically managed hip fractures was reported to be 75–90%.

Scores and scorecard

Scores were developed for Burden of disease and the healthcare provision (Policy framework, Service provision and Service uptake) in the EU27+2 countries. Bulgaria scores resulted in an 18th place regarding Burden of disease. The combined healthcare provision scorecard resulted in a 22nd place for Bulgaria. Thus, Bulgaria presents as one of the five low-burden low-provision countries among the EU27+2.

Fig. 1 Scores by country for metrics related to policy framework, service provision and service uptake. The mean score for each of the 3 domains is given. An asterisk denotes that there was one or more missing metric which decreases the overall score

The first SCOPE was undertaken in 2010, almost 10 years previously. Fifteen of the 16 score card metrics on healthcare provision were used in the two surveys. Scores had improved or markedly improved in 15 countries, remained constant in 8 countries and worsened in 3 countries. For Bulgaria, the scores were somewhat improved.

Fig. 2 The scorecard for all the EU27+2 countries illustrating the scores across the four domains. The elements of each domain in each country were scored and coded using a traffic light system (red, orange, green). Black dots signify missing information

The second edition of the Scorecard for Osteoporosis in Europe (SCOPE 2021) allows health and policy professionals to assess key indicators on the healthcare provision for osteoporosis within countries and between countries within the EU 27+2. The scorecard is not intended as a prescriptive template. Thus, it does not set performance targets but may serve as a guide to the performance targets at which to aim in order to deliver the outcomes required.

Acknowledgements

SCOPE was supported by an unrestricted grant from Amgen to the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF). Amgen was neither involved in the design nor writing of the report. We are grateful to Anastasia Soulié Mlotek and Dominique Pierroz of the IOF for their help in the administration of SCOPE. The report has been reviewed by the members of the SCOPE Consultation Panel and the relevant IOF National societies, and we are grateful for their local insights on the management of osteoporosis in each country. The source document has been reviewed and endorsed by the Committee of Scientific Advisors of the IOF and benefitted from their feedback.

References

1. Kanis JA, Norton N, Harvey NC, Jacobson T, Johansson H, Lorentzon M, McCloskey EV, Willers C, Borgström F (2021) SCOPE 2021: a new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe. Arch Osteoporos 16:82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-020-00871-9

2. World Health Organisation (1994) Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser, 1994/01/01 edn, pp 1-129

3. Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Sernbo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Petterson C, De Laet C, Jonsson B (2004) Mortality after osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 15:38-42

4. Kirilova E, Johansson H, Kirilov N, Vladeva S, Petranova T, Kolarov Z, Liu E, Lorentzon M, Vandenput L, Harvey NC, McCloskey E, Kanis JA (2020) Epidemiology of hip fractures in Bulgaria: development of a country-specific FRAX model. Arch Osteoporos 27;15(1):28.

5. Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergard M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J, McCloskey EV, Jonsson B, Kanis JA (2013) Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 8:136

6. Allen P, Pilar M, Walsh-Bailey C, Hooley C, Mazzucca S, Lewis CC, Mettert KD, Dorsey CN, Purtle J, Kepper MM, Baumann AA, Brownson RC (2020) Quantitative measures of health policy implementation determinants and outcomes: a systematic review. Implement Sci 15:47

7. Borgstrom F, Karlsson L, Ortsater G, Norton N, Halbout P, Cooper C, Lorentzon M, McCloskey EV, Harvey NC, Javaid MK, Kanis JA (2020) Fragility fractures in Europe: burden, management and opportunities. Arch Osteoporos 15:59

8. Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oglesby AK (2003) The components of excess mortality after hip fracture. Bone 32:468-473

9. National Clinical Guideline Centre (2011) The Management of Hip Fracture in Adults. In Centre NCG (ed) London

Epidemiology and economic burden of osteoporosis in Croatia

S Grazio ∙ V Altabas ∙ Z Giljević∙ C Willers ∙ N Norton ∙ NC Harvey ∙ T Jacobson ∙ H Johansson ∙ M Lorentzon ∙ EV McCloskey ∙ F Borgström ∙ JA Kanis

Introduction

The scorecard summarises key indicators of the burden of osteoporosis and its management in the 27 member states of the European Union, as well as the UK and Switzerland (termed EU27+2) [1]. This country-specific report summarises the principal results for Croatia.

Methods

The information obtained covers four domains: burden of osteoporosis and fractures; policy framework; service provision; and service uptake. Data were collected from numerous sources including previous research and IOF reports, and available registers which were used for additional analysis of resource utilization, costing and HRQoL data. Furthermore, country-specific information on osteoporosis management was obtained from each IOF member state via a questionnaire.

Burden of disease

The direct cost of incident fractures in Croatia in 2019 was €71.3 million. Added to this was the ongoing cost in 2019 from fractures that occurred before 2019, which amounted to €58.6 million (long-term disability). The cost of pharmacological intervention (assessment and treatment) was €6.1 million. Thus, the total direct cost (excluding the value of QALYs lost) amounted to €136 million in 2019. Key metrics are presented in Table 1.

In 2019, the average direct cost of osteoporotic fractures in Croatia was €31.8 per individual. Data for 2010 were not available to assess the development, but the 2019 numbers put Croatia in 24th place in terms of highest cost of osteoporotic fractures per capita in the EU27+2.

The cost of osteoporotic fractures in Croatia accounted for approximately 3.9% of healthcare spending (i.e. €136 million out of €3.3 billion in 2019), slightly higher than the EU27+2 average of 3.5% and placed Croatia in 10th place in the rank order of the EU27+2 countries These numbers indicate a substantial impact of fragility fractures on the healthcare budget.

Using World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis based on the measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) [2], there were approximately 252,000 individuals with osteoporosis in Croatia in 2019, of whom approximately 80% were women. The prevalence of osteoporosis in the total Croatian population amounted to 5.5%, on par with the EU27+2 average (5.6%).

Table 1 Key measures of burden of disease for Croatia

Category | Measure | Estimate | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

Burden of disease | Direct cost of incident fracture (€m) | 71.30 | |

Long-term disability cost (€m) | 58.55 | ||

Intervention cost (€m) | 6.08 | ||

Total cost (€m) | 135.93 | ||

QALYs lost (€m) | 373 | ||

Cost per capita (€) | 31.75 | 24 | |

Proportion of healthcare spending | 3.9% | 10 | |

Prevalence of osteoporosis | 5.5% | 13 |

There were estimated to be 35,000 new fragility fractures in Croatia in 2019, equivalent to 96 fractures/day (or 4 per hour). The remaining lifetime probability of hip fracture (%) at the ages of 50 years in men and women was 5.1% and 11.4%, respectively, placing Croatia in the middle tertile of risk for men and the lower tertile of risk for women.

Some osteoporotic fractures are associated with premature mortality [3]. In Croatia, the annual number of deaths associated with a fracture event was estimated to be 172 per 100,000 individuals of the population aged 50 years or more, compared to the EU27+2 average of 116/100,000. The number of fracture-related deaths is comparable to or exceeds that for some of the most common causes of death such as lung cancer, diabetes, chronic lower respiratory diseases.

The population of men and women age 50 years or more is projected to increase by 2.8% between 2019 and 2034, a significantly smaller increase than the EU27+2 average of 11.4%. The increases in men and women aged 75 years or more in Croatia are more marked and amount to 41.0% and 17.3%, respectively. The annual number of osteoporotic fractures in Croatia is expected to increase by 4,000 to 39,000 in 2034.

Policy framework (Table 2)

Documentation of the burden of disease is an essential prerequisite to determine the resources that should be allocated to the diagnosis and treatment of the disorder. High quality national data on hip fracture rates have been identified in 18 of 29 countries, of which Croatia is one. Data are collected on a national basis and include more than only hip fracture data.

Given that osteoporosis and fragility fractures are common and that effective treatments are widely available, the vast majority of patients with osteoporosis are preferably managed at the primary health care level by general practitioners (GPs), with specialist referral reserved for difficult complex cases. Primary care was the principal provider of the medical care for osteoporosis in 13 of the 28 countries where data were available. For Croatia, this was not the case, and the lead specialty for osteoporosis was reported to be endocrinology.

Osteoporosis and metabolic bone disease is not a recognised specialty in most countries including Croatia. Specialty care of osteoporosis in Croatia is managed via other specialties including endocrinology, rehabilitation medicine, orthopaedics and gynaecology. Osteoporosis is however recognized as a component of specialty training. Although it is possible that these specialties educate their trainees adequately, the wide variation may reflect inconsistencies in patient care, training of primary care physicians and a suboptimal voice to “defend” the interests of those who work within the field of osteoporosis.

Table 2 Policy framework for osteoporosis in Croatia

Category | Measure | Estimate |

|---|---|---|

Policy framework | National fracture data availability | No |

OP recognized as a specialty | No | |

OP primarily managed in primary care | No | |

Other specialties involved | Endocrinology, Rehabilitation medicine, Orthopaedics, Gynaecology | |

Advocacy areas covered by patient organisation | Policy, capacity, peer support |

The role of national patient organisations is to improve the care of patients and increase awareness and prevention of osteoporosis and related fractures among the general public. Advocacy by patient organisations can fall into four categories: policy, capacity building and education, peer support, research and development. For Croatia, three of these four advocacy areas were covered by a patient organisation. All advocacy areas were covered for only 10 out of the 26 countries with at least one patient organisation.

Service provision (Table 3)

A wide variety of approved drug treatments is available for the management of osteoporosis [4]. Potential limitations of their use in member states relate to reimbursement policies which may impair the delivery of health care. Croatia is one of the 12 (out of 27) countries that offer full reimbursement.

The assessment of bone mineral density forms a key component for the general management of osteoporosis, being used for diagnosis, risk prediction, selection of patients for treatment and monitoring of patients on treatment. In Croatia, the number of DXA units expressed per million of the general population amounted to 10.8 which puts the country in the 19th place among the EU27+2.

The average waiting time for DXA ranged from 0 to 180 days across countries, and there was no clear relation between waiting times and the availability of DXA. In Croatia, the estimated average waiting time for DXA amounted to 21 days. 16 countries reported shorter average waiting times. Reimbursement for DXA scans varied between member states both in terms of the criteria required and level of reimbursement awarded.

Table 3 Service provision for osteoporosis in Croatia

Category | Measure | Estimate | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

Service provision | Reimbursement of OP medications | 100% | |

DXA units/million inhabitants | 10.8 | 19 | |

DXA cost (€) | 25 | 22 | |

FRAX risk assessment model available | Yes | ||

Fracture liaison service density | No FLS |

The effective targeting of treatment to those at highest risk of fracture requires an assessment of fracture risk. Risk assessment models for fractures, most usually based on FRAX, were available in 24 out of 29 countries, of which Croatia was one. For Croatia, guidance on the use of risk assessment within national guidelines was not available, as was the case in 14 of the EU27+2 countries.

Guidelines for the management of osteoporosis were available in Croatia (as in 27 out of 29 countries). The guidelines in Croatia included postmenopausal women specifically, as well as osteoporosis in men and secondary osteoporosis including glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.

Fracture liaison services (FLS), also known as osteoporosis coordinator programmes and care manager programmes, provide a system for the routine assessment and management of postmenopausal women and older men who have sustained a low trauma fracture. No fracture liaison services were reported from Croatia (together with 7 other countries).

The use of indicators to systematically measure the quality of care provided to people with osteoporosis or associated fractures has expanded as a discipline within the past decade [5]. No use of national quality indicators was reported for Croatia.

Service uptake (Table 4)

The web-based usage of FRAX showed considerable heterogeneity in uptake between the countries. The average uptake for the EU27+2 was 1,555 sessions/million/year of the general population with an enormous range of 49 to 41,874 sessions/million. The usage for Croatia amounted to 629 sessions/million.

Many studies have demonstrated that a significant proportion of men and women at high fracture risk do not receive therapy for osteoporosis (the treatment gap) [6]. In the EU27+2 the average treatment gap was 71% but ranged from 32 to 87%. For Croatia, the treatment gap amongst women amounted to 82% or 138,000 out of 169,000 characterised at risk. The Croatian treatment gap increased with approximately 15% compared to 2010. The average treatment gap among EU27+2 increased from 55% in 2010 to 71% in 2019.

Table 4 Service uptake for osteoporosis in Croatia

Category | Measure | Estimate | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

Service uptake | Number of FRAX sessions/million people/year | 629 | 17 |

Treatment gap for women eligible for treatment (%) | 82 | 22 | |

Proportion surgically managed hip fractures | >90% |

About 5% of people with a hip fracture die within 1 month of their fracture [7]. A determinant of peri-operative morbidity and mortality is the time a patient takes to get to surgery [8]. For Croatia, the average waiting time for hip fracture surgery after hospital admission was reported to be less than 24 h. The proportion of surgically managed hip fractures was reported to be over 90%.

Scores and scorecard

Scores were developed for Burden of disease and the healthcare provision (Policy framework, Service provision and Service uptake) in the EU27+2 countries. Croatia scores resulted in a 19th place regarding Burden of disease. The combined healthcare provision scorecard resulted in a 24th place for Croatia. Thus, Croatia presents as one of the low-burden low-provision countries among the EU27+2.

Fig. 1 Scores by country for metrics related to policy framework, service provision and service uptake. The mean score for each of the 3 domains is given. An asterisk denotes that there was one or more missing metric which decreases the overall score

The first SCOPE was undertaken in 2010, almost 10 years previously. Fifteen of the 16 score card metrics on healthcare provision were used in the two surveys. Scores had improved or markedly improved in 15 countries, remained constant in 8 countries and worsened in 3 countries. For Croatia data for comparison to 2010 were not available.