Abstract

Summary

Osteoporosis medications are recommended for elderly patients after a fragility fracture. However, we found substantial under-treatment in the post-fracture year, especially among patients who had not previously received such medications. Improved treatment of elderly patients experiencing fragility fractures is needed.

Introduction

Osteoporosis medications are recommended for elderly patients after a fragility fracture, but under-treatment is common. We determined osteoporosis medication use after fragility fractures and examined associated factors.

Methods

Our cohort included elderly (age ≥66 years) Medicare-enrolled patients who sustained fragility fractures January 1, 2008–December 31, 2011. Osteoporosis medication prescriptions were determined in the 12 months after the index fracture. Using multivariate logistic models, we examined the association between post-fracture osteoporosis medication use and predictors.

Results

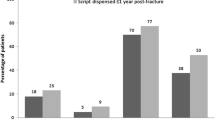

Of 145,185 patients with fragility fractures (mean age 80.9 ± 7.8 years; 91.2 % white; 81.3 % female), 29.9 % sustained hip, 31.8 % vertebral, and 38.4 % non-hip-non-vertebral fractures. Overall, 30.4 % of the cohort received an osteoporosis medication in the 12-month post-fracture period. Of patients not receiving an osteoporosis medication in the pre-index period (n = 108,344), 14.9 % of all patients, 16.3 % of women, and 10.3 % of men received one in the post-fracture period. Corresponding values for patients receiving an osteoporosis medication in the pre-index period (n = 36,841) were 76.2, 76.5, and 72.2 %. Odds of post-fracture osteoporosis medication use were 68 % higher for women than for men. Osteoporosis diagnosis (odds ratio, 1.55; P < 0.0001) and bone-mineral-density tests before an index fracture (odds ratio, 1.24; P < 0.001) were associated with post-fracture osteoporosis medication use.

Conclusions

Less than one third of our cohort received an osteoporosis medication in the post-fracture year, when risk of a second fragility fracture is highest. In those not already previously treated with an osteoporosis medication, only about 1 in 7 patients received treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Marks R, Allegrante JP, MacKenzie CR, Lane JM (2003) Hip fractures among the elderly: causes, consequences and control. Ageing Res Rev 2:57–93

Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A (2007) Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res 22:465–475

Dempster DW (2011) Osteoporosis and the burden of osteoporosis-related fractures. Am J Manag Care 17(Suppl 6):S164–S169

Rousculp MD, Long SR, Wang S, Schoenfeld MJ, Meadows ES (2007) Economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in Medicaid. Value Health 10:144–152

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Odén A, Sernbo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Petterson C, De Laet C, Jönsson B (2004) Fracture risk following an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 15:175–179

Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, Abbott TA III, Berger M (2000) Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res 15:721–739

North American Menopause Society (2010) Management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: 2010 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 17:25–54

Florence R, Allen S, Benedict L, Compo R, Jensen A, Kalogeropoulou D, Kearns A, Larson S,Mallen E, O'Day K, Peltier A, Webb B (2013) Diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/vnw0c3/osteo.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2016

Balasubramanian A, Tosi LL, Lane JM, Dirschl DR, Ho PR, O'Malley CD (2014) Declining rates of osteoporosis management following fragility fractures in the US, 2000 through 2009. J Bone Joint Surg Am 96:e52

Solomon DH, Johnston SS, Boytsov NN, McMorrow D, Lane JM, Krohn KD (2014) Osteoporosis medication use after hip fracture in US patients between 2002 and 2011. J Bone Miner Res 29:1929–1937

Kiebzak GM, Beinart GA, Perser K, Ambrose CG, Siff SJ, Heggeness MH (2002) Undertreatment of osteoporosis in men with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med 162:2217–2222

Shibli-Rahhal A, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Richardson K, Cram P (2011) Testing and treatment forosteoporosis following hip fracture in an integrated U.S. healthcare delivery system. Osteoporos Int 22:2973–2980

Jennings LA, Auerbach AD, Maselli J, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK, Lee SJ (2010) Missed opportunities for osteoporosis treatment in patients hospitalized for hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 58:650–657

National Committee for Quality Assurance (2013) The state of health care quality 2013. Improvingquality and patient experience. Available at: http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/Newsroom/SOHC/2013/SOHC-web_version_report.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2016

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (2014) Osteoporosis/bone health in adults as a national public health priority. Position statement. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/about/papers/position/1113.asp. Accessed July 13, 2016

Curtis JR, Mudano AS, Solomon DH, Xi J, Melton ME, Saag KG (2009) Identification and validation of vertebral compression fractures using administrative claims data. Med Care 47:69–72

Song X, Shi N, Badamgarav E, Kallich J, Varker H, Lenhart G, Curtis JR (2011) Cost burden of second fracture in the US health system. Bone 48:828–836

Crandall CJ, Newberry SJ, Diamant A, Lim YW, Gellad WF, Booth MJ, Motala A, Shekelle PG (2014) Comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic treatments to prevent fractures. Ann Intern Med 161:711–723

Kanis JA, Svedbom A, Harvey N, McCloskey EV (2014) The osteoporosis treatment gap. J Bone Miner Res 29:1926–1928

Lems WF (2015) Fracture risk estimation may facilitate the treatment gap in osteoporosis. Ann Rheum Dis 74:1943–1945

MacLaughlin EJ (2010) Improving osteoporosis screening, risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment initiation: role of the health-system pharmacist in closing the gap. Am J Health Syst Pharm 67(Suppl 3):S4–S8

Eisman JA, Bogoch ER, Dell R, Harrington JT, McKinney RE Jr, McLellan A, Mitchell PJ, Silverman S, Singleton R, Siris E, ASBMR Task Force on Secondary Fracture Prevention (2012) Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force report on secondary fracture prevention. J Bone Miner Res 27:2039–2046

Akesson K, Marsh D, Mitchell PJ, McLellan AR, Stenmark J, Pierroz DD, Kyer C, Cooper C, IOF Fracture Working Group (2013) Capture the fracture: a best practice framework and global campaign to break the fragility fracture cycle. Osteoporos Int 24:2135–2152

Mitchell PJ (2013) Best practices in secondary fracture prevention: fracture liaison services. Curr Osteoporos Rep 11:52–60

Huntjens KM, van Geel TA, van den Bergh JP, van Helden S, Willems P, Winkens B, Eisman JA, Geusens PP, Brink PR (2014) Fracture liaison service: impact on subsequent nonvertebral fracture incidence and mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am 96:e29

Nakayama A, Major G, Holliday E, Attia J, Bogduk N (2016) Evidence of effectiveness of a fracture liaison service to reduce the re-fracture rate. Osteoporos Int 27:873–879

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a research grant from Amgen Inc. The contract provides for the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation authors to have final determination of manuscript content. Drs. Yusuf, Grauer, Barron, and Chandler are employed by Amgen. The authors thank Chronic Disease Research Group colleague Nan Booth, MSW, MPH, ELS, for manuscript editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

We applied to and received approval from the Human Subjects Research Committee of the Hennepin County Medical Center/Hennepin Healthcare System, Inc.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 28 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yusuf, A.A., Matlon, T.J., Grauer, A. et al. Utilization of osteoporosis medication after a fragility fracture among elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Osteoporos 11, 31 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-016-0285-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-016-0285-0